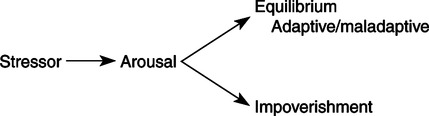

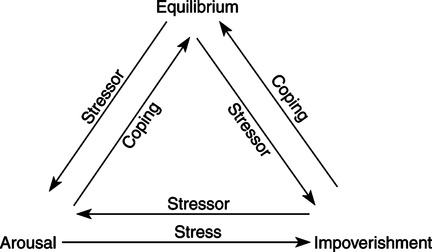

“Unconditional acceptance of the person as a human in the process of Being and Becoming is basic to the Modeling and Role-Modeling paradigm. It is a prerequisite to facilitating holistic growth … Unconditional acceptance of the person as a human being who has an inherent need for dignity and respect from others, and for connectedness—that kind of Unconditional Acceptance is based on Unconditional Love” (Erickson, 2006, p. 343). The theory and paradigm Modeling and RoleModeling was developed using a retroductive process. The original model was derived inductively from the primary author’s clinical and personal life experiences. The works of Maslow, Erikson, Piaget, Engel, Selye, and M. Erickson were then integrated and synthesized into the original model to label, further articulate, and refine a holistic theory and paradigm for nursing. Erickson (1976) argued that people have mind-body relations and an identifiable resource potential that predicts their ability to contend with stress. She also articulated a relationship between needs status and developmental processes, satisfaction with needs and attachment objects, loss and illness, and health and need satisfaction. Tomlin and Swain validated and affirmed Erickson’s practice model and helped to expand and articulate labeled phenomena, concepts, and theoretical relationships. The authors used Maslow’s theory of human needs to label and articulate their personal observations that “all people want to be the best that they can possibly be; unmet basic needs interfere with holistic growth whereas satisfied needs promote growth” (Erickson, Tomlin, & Swain, 2002, p. 56; Jensen, 1995). The authors further integrated the model to state that unmet basic needs create need deficits, which can lead to initiation or aggravation of physical or mental distress or illness. At the same time, need satisfaction creates assets that provide resources needed to contend with stress and promote health, growth, and development. Piaget’s theory of cognitive development provides a framework for understanding the development of thinking. On the other hand, integration of Erik Erikson’s work on the stages of psychosocial development through the life span provides a theoretical basis for understanding the psychosocial evolution of the individual. Each of his eight stages represents developmental tasks. As an individual resolves each task, he or she gains strengths that contribute to character development and health. Furthermore, as an outcome of each stage, people develop a sense of their own worth and, therefore, a projection of themselves into the future. “The utility of Erikson’s theory is the freedom we may take to view aspects of people’s problems as uncompleted tasks. This perspective provides a hopeful expectation for the individual’s future since it connotes something still in progress” (Erickson et al., 2002, pp. 62-63). The authors further state, “object loss results in basic need deficits” (Erickson et al., 2002, p. 88). Loss is real, threatened, or perceived; it may be a normal part of the developmental process, or it may be situational. Loss always results in grief; normal grief is resolved in approximately 1 year. When only inadequate or inappropriate objects are available to meet needs, morbid grief results. Morbid grief interferes with the individual’s ability to grow and develop to maximal potential. The work of Selye and Engel, as cited by Erickson, Tomlin, and Swain (1983), provided an additional conceptual basis for the beliefs the theorists hold regarding loss and an individual’s stress responses to that loss or losses. Selye’s theory pertains to an individual’s biophysical responses to stress, whereas Engel’s work explores the psychosocial responses to stressors. The synthesis of these theories, with the integration of the primary author’s clinical observations and lived experiences, resulted in the development of the Adaptive Potential Assessment Model (APAM). The APAM focuses on the individual’s ability to mobilize resources when confronted with stressors, rather than the adaptation process. This model was first developed by Erickson (1976) and was later described in publication by Erickson and Swain (1982). Several studies have provided initial evidence for philosophical premises and theoretical linkages implied in the original book by Erickson, Tomlin, and Swain (1983), and later specified by Erickson (1990b). The APAM (Figures 25-1 and 25-2) has been tested as a classification model (Barnfather, 1987; Erickson, 1976; Kleinbeck, 1977) and as a predictor for health status (Barnfather, 1990b) and for length of hospital stay (Erickson & Swain, 1982), as it relates to basic need status (Barnfather, 1993). Findings from these studies provide beginning evidence for the proposed three-state model across populations, a relationship between health and ability to mobilize resources, and an ability to mobilize resources and needs status. Two other studies have shown relationships among stressors (measured as life events) and propensity for accidents (Babcock & Mueller, 1980) and resource state and ability to take in and use new information (Clementino & Lapinske, 1980). Finally, Benson (2003) has studied the APAM as applied to small groups. Relationships among self-care knowledge, resources, and activities have been demonstrated in several studies (Acton, 1993; Baas, 1992; Irvin, 1993; Jensen, 1995; Miller, 1994). The self-care knowledge construct, first studied by Erickson (1985), was replicated and found to be significantly associated with perceived control (Cain & Perzynski, 1986) and quality of life (Baas, Fontana, & Bhat, 1997). Self-directedness, need for harmony (affiliation), and need for autonomy (individuation) were found when multidimensional scaling was used to explore relationships among self-care knowledge, resources, and actions. The author concluded that a positive attitude was a major factor when health-directed self-care actions were assessed (Rosenow, 1991). Physical activity in patients after myocardial infarction was shown to be affected by life satisfaction (not physical condition); life satisfaction was predicted by availability of self-care resources and resources needed. Furthermore, resources needed served as a suppressor for resources available (Baas, 1992). In a sample of caregivers, social support predicted for stress level and self-worth had an indirect effect on hope through self-worth (Irvin, 1993; Irvin & Acton, 1997), whereas persons with diabetes with spiritual well-being were better able to cope (Landis, 1991). When the Modeling and Role-Modeling Theory was used as a guideline, interviews were used to determine the client’s model of the world. The following seven themes emerged (Erickson, 1990a): 1. Cause of the problem, which was unique to the individual 2. Related factors, also unique to the individual 3. Expectations for the future Each model was unique and each warranted individualized interventions. Other qualitative studies on self-care knowledge showed that acutely ill patients perceived monitoring, caring, presence, touch, and voice tones as comforting (Kennedy, 1991); healthy adults sought need satisfaction from the nurse practitioner in primary care (Boodley, 1990, 1986); and hospice patients benefited from nurse empathy (Raudonis, 1991). Studies also showed relationships among mistrust and length of stay in hospitalized subjects (Finch, 1990); perceived enactment of autonomy, self-care, and holistic health in the elderly (Anschutz, 2000; Hertz & Anschutz, 2002); perceived support, control, and well being in the elderly (Chen, 1996); and loss, morbid grief, and onset of symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease (Erickson, Kinney et al., 1994; Irvin & Acton, 1996). Other studies addressed linkages between role-modeled interventions and outcomes (Erickson, et al., 1994; Hertz, 1991; Irvin, 1993; Jensen, 1995; Kennedy, 1991). College level students who perceived satisfaction of needs were more successful in school. Seven nursing students who perceived that they were supported were more able to attain their goals for advanced education (Smith, 1980), the elderly who felt supported reported higher need satisfaction and were better able to cope (Keck, 1989), adolescent mothers who felt supported and perceived need satisfaction had a more positive maternal-infant attachment (Erickson, M., 2006; Erickson, M., 1996a; Erickson, M., 1996b), those with a strong social network reported better health (Doornbos, 1983), and persons convicted of sexual offenses and then were provided with support to remodel their worlds were able to develop new behaviors and move on with their lives (Scheela, 1991). Families and post–myocardial infarction patients who were able to participate in planning their own care through contracting had less anxiety and better perceived control and perceived support (Holl, 1992), and caregivers of adults with dementia who experienced theory-based nursing using the Modeling and Role-Modeling Theory perceived that their needs were met and that they were healthier (Hopkins, 1995). They also reported feeling that they were encouraged, which helped them accept the situation and transcend the experience of caregiving (Hopkins, 1995). Self-care resources, measured as needs, are related to perceived support and coping in women with breast cancer (Keck, 1989), physical well-being in persons with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Kline, 1990, 1988), and anxiety in hospitalized patients who have had cardiac surgery and their families (Holl, 1992). Finally, when AI was tested as a buffer between stress and well-being, a mediation effect was found (Acton, 1997; Acton, 1993; Acton, Irvin, Jensen, Hopkins, & Miller, 1997). Other studies that operationalized self-care resources by measuring developmental residuals have shown that identity resolution in adolescents with facial disfiguration can be predicted by previous developmental residual (Miller, 1986). Chen (1996) found that feelings of control over one’s health (health control orientation) status in elderly individuals with hypertension correlated highly with self-efficacy and self-care. In addition, her work supported that health control orientation, self-efficacy, and self-care were associated with well-being. Through interviews of older adults living independently, Hertz, Rossetti, and Nelson (2006) were able to identify categories of self-care actions that encompassed important self-care activities. Other researchers found that trust predicts for adolescent clients’ involvement in the prescribed medical regimen (Finch, 1987), perceived support and adaptation are related to developmental residual in families with newborn infants (Darling-Fisher, 1987; Darling-Fisher & Leidy 1988), mistrust predicts length of hospital stay, and positive residual serves as a buffer (Finch, 1987). Positive residual in the intimacy stage of healthy adults predicts for health behaviors (MacLean, 1992, 1990, 1987), developmental residual predicts for hope, trustmistrust residual predicts for generalized hope, autonomy-shame and doubt residual predicts for particularized hope in the elderly (Curl, 1992), and negative residual is related to speed and impatience behaviors in a healthy sample of military personnel (Kinney, 1992). Case study methods have been used to show relationships among needs, attachment, and developmental residual (Kinney, 1990, 1992; Kinney & Erickson, 1990) and needs and coping (Jensen, 1995), and two unpublished studies have shown relationships between healthy adults and need status (Erickson, Kinney, Stone, & Acton, 1990). Studies have also been used to explore self-care knowledge in informants in the hospital (Erickson, 1985), perceived enactment of autonomy and life satisfaction in the elderly (Anschutz, 2000), the experience of persons 85 and older as they manage their health (Beltz, 1999), perceptions of hope in elementary school children (Baldwin, 1996), the experiential meaning of well-being and the lived experience in employed mothers (Weber, 1995, 1999), developmental growth in adults with heart failure (Baas, Beery, Fontana, & Wagoner, 1999), the individual’s ability to mobilize coping resources and basic needs (Barnfather, 1990a), the relationship between basic need satisfaction and emotionally motivated eating (Timmerman & Acton, 2001), relations among hostility, self-esteem, self-concept, and psychosocial residual in persons with coronary heart disease (Sofhauser, 1996), and the human-environment relationship when healing from an episodic illness (Bowman, 1998). Studies have explored the relationship between spiritual well-being and heart failure (Beery, Baas, Fowler, & Allen, 2002), spirituality in caregivers of family members with dementia (Acton & Miller, 1996), the implementation of a mind, body, spirit self-empowerment program for adolescents (Nash, 2007) and women with breast cancer (Kinney, Rodgers, Nash, & Bray, 2003), the meaning and impact of suffering in people with rheumatoid arthritis (Dildy, 1992), and the relationship between experiences of prolonged family suffering and evolving spiritual identity (Clayton, 2001). Studies with cardiovascular have continued as Baas (2004) studied self-care resources and quality of life in patients following myocardial infarction, and Baas et al. (2004) explored body awareness in heart failure or transplant patients. Similarly, Beery, Baas, Mathews, Burrough, and Henthorn (2005) developed an adjustment scale to measure self-report with implanted devices in cardiac patients, and Beery, Baas, and Henthorn (2007) reported on patient adjustments to the devices. Tools that have been developed to test the Modeling and Role-Modeling Theory include the Basic Needs Satisfaction Inventory (Kline, 1988), the Erikson Psychosocial Stage Inventory (Darling-Fisher & Leidy, 1988), the Perceived Enactment of Autonomy tool designed to measure a prerequisite to self-care actions in the elderly (Hertz, 1991, 1999; Hertz & Anschutz, 2002), the Self-Care Resource Inventory (Baas, 1992), the Robinson Self-Appraisal Inventory designed to measure denial (the first stage in the grief process) in patients after myocardial infarction (Robinson, 1992), the Erickson Maternal Bonding-Attachment Tool designed to measure self-care knowledge as motivational style (deficit or being motivation) and self-care resource (Erickson, M., 1996b), a theory-based nursing assessment (Finch, 1990), and the Hopkins Clinical Assessment of the APAM (Hopkins, 1995).

Modeling and Role-Modeling

THEORETICAL SOURCES

USE OF EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree