7. Minor head injuries

Currie (1993) listed the dilemmas facing the doctor who deals with a head-injured patient. These included: which of these patients needed a skull X-ray, who should be admitted, have a computerised tomographic (CT) scan, have surgery, be ventilated? The criteria for making those decisions have changed since 1993. Subsequent issues of national guidelines for the care of head-injured patients, and for the use of radiology departments by the Royal College of Radiologists have reduced the role of plain X-rays and in-patient observation as tools for detecting the significant presentations, and increased the role of CT scanning.

However, at the point of first contact with the patient, the question remains the same. Which of the many people who pass through your department complaining of injuries to the head have suffered a significant injury to the brain? Should this patient be sent home or kept in hospital, to be observed, or scanned?

Patients with minor head injuries are a large part of the population which attends minor injury facilities. The tools for assessing them there are almost exclusively clinical: but there is no clinical tool which will tell you beyond doubt that a serious injury is not present. Therefore the whole business of managing minor head injuries is fraught with the risk that your best efforts on a patient’s behalf will fail to detect such an injury.

Your management of the patient calls upon a combination of clinical assessment, statistics, clinical guidelines based on those statistics and social precautions for the patient after he leaves your unit. Behind the use of all of those tools is a nagging awareness that none of them guarantees the well-being of the patient in front of you. Sometimes you may have a sense that all is not well with a patient in spite of the fact that none of your assessments have revealed a deficit. And sometimes events prove the validity of that ‘gut feeling’. You must have the confidence to discharge those patients who seem to be well, and to retain those who cause concern.

This chapter explores the grounds upon which these choices might be made. Head injuries in children are discussed in Chapter 2.

Anatomy

The brain and spinal cord are, together, the central nervous system. The neural tissues of the brain are delicate and damage to them is irreversible.

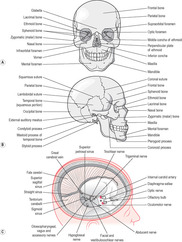

The cranial part of the skull (Figure 7.1) is a bony box which holds and protects the brain. The bones which contribute to this structure are the frontal, parietal, temporal and occipital.

The box is not a sealed container. It has many openings to permit the passage of blood vessels and nerves and a large passage in its occipital floor, the foramen magnum, through which the brainstem gives way to the spinal cord. It then passes into the vertebral canal of the spine. However, neither these openings nor the joints between the various bones of the cranium provides sufficient leeway to absorb the extra pressure which occurs inside the cranium if there is bleeding caused by injury or if the brain should swell (cerebral oedema). The effects of raised intracranial pressure are transmitted to the soft brain itself, and its rigid protective environment becomes a liability. Violent impacts or sudden movements of the head can throw the brain against the hard edges and surfaces of the cranial bones, resulting in contusion and damage to the brain.

The brain has other forms of protection. It is covered by three layers of protective fibrous material, the meninges. The innermost layer is the pia mater (meaning tender mother). This is a fine, richly vascular tissue which clothes the outline of the brain. The middle layer is the arachnoid (meaning cobweb), a layer of fine tissue which is separated from the pia mater by the subarachnoid space and joined to it by web-like attachments, which give the arachnoid its name. The subarachnoid space contains cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and blood vessels. The outer layer is the dura mater (meaning hard mother), a tough tissue which covers brain and forms the dural sheath around the spinal cord. Bleeding which occurs in the space between the skull and the dura mater (epidural haemorrhage) is usually caused by trauma to the temporal bone, causing fracture and bleeding from the meningeal artery. The patient deteriorates very quickly and needs immediate surgery to remove the haematoma. A subdural haemorrhage is venous and the patient may not deteriorate so quickly.

The brain floats in, and is protected and nourished by, CSF, a liquid formed from, and similar to, plasma. The spinal cord is also surrounded by this liquid. The level of CSF in the brain is delicately regulated to avoid excess pressure.

Our state of consciousness, of awareness in the world, resides in the brain and can be extinguished there. The brain is the centre where all those functions of our inner life that we might call thought and feeling arise. The brain regulates the body, its internal environment and its responses to external changes. It receives the signals from the five senses and translates them into the experiences which we call sight, smell, sound, taste and sensation. It sends out the signals which enable us to act in the world. The vast array of cerebral functions is relegated to specialised zones in the brain. The part of the brain which lies at its base, the brainstem, is of particular concern in the head-injured person who is suffering from the effects of rising intracranial pressure. This area regulates vital functions such as breathing, heartbeat and consciousness itself. Increased pressure on the brain will tend to drive the brainstem into the foramen magnum, the access point to the spinal canal, a fatal process called coning.

Minor head injuries and imaging

Many patients attend minor injury clinics with injuries to the head or face, which might be called ‘head injuries’ in the anatomical sense but are more appropriately categorised as lacerations to scalp, or eyebrow or wherever.

A common tale is of a clash of heads on the rugby field, where the patient does not know that he is injured until some blood runs down into his eye, or of a workman who stands up below a shelf with a sharp corner and cuts the top of the head. The injured person has an instant of sharp, superficial pain and no other symptom except the bleeding, which brings the patient for treatment.

Patients with problems of this kind must be assessed neurologically as well as having the superficial injury treated, and they will be sent home with a sheet of head injury instructions along with advice on the care of staples or sutures.

There is clearly a difference between that kind of event, and the kind of event where a patient is brought to your unit, pale and shaken, upset, unable to remember his injury, complaining of a headache and vomiting repeatedly. He is brought in by someone who says that he has just fallen 10 feet from a ladder and hit the back of the head on a concrete path. This patient may also have a laceration, but that will not be your first concern.

Wrightson & Gronwall (1999) offer a definition of ‘mild’ head injury for patients when they are first seen which incorporates a minimum degree of severity and an upper limit to the severity of the injury. These are, on the minimum side, that the patient should have suffered ‘an injury to the head resulting from physical force’ and that neurological function has been disturbed, with symptoms such as confusion, amnesia, altered consciousness, headache or unexplained vomiting. The upper limit of severity in a patient who has just presented is that the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) (Table 7.1) should not be lower than 13 and that there should be no focal neurological abnormality, such as hemiparesis or cranial nerve damage. Patients with a GCS of 13 may be assessed as having a more severe injury if they do not improve during a period of observation of 4 hours. (It does not sound as if a loss of two GCS points is large, but, in fact, a sober patient who has trouble keeping his eyes open after a head injury is a disturbing sight even if there is no other change.)

| Category | Score |

|---|---|

| Eye opening | |

| Spontaneous | 4 |

| To speech | 3 |

| To pain | 2 |

| None | 1 |

| Best verbal response | |

| Orientated conversation | 5 |

| Confused conversation | 4 |

| Inappropriate words | 3 |

| Incomprehensible sounds | 2 |

| None | 1 |

| Best motor response | |

| Obeying commands | 6 |

| Localises pain | 5 |

| Flexion withdrawal from pain (normal flexion) | 4 |

| Abnormal flexion (decorticate rigidity) | 3 |

| Abnormal extension (decerebrate rigidity) | 2 |

| None | 1 |

Unconsciousness is not mentioned in this definition because it can be hard to find out how long, and how profound an episode has been.

It is clear from the definition, which makes no mention of fracture of the skull, that some evidence of injury to the brain is the element which is considered to be important, and you will be looking for signs of that, and for signs that the patient is getting worse.

The Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) has issued a set of guidelines for the care of head-injured patients (2009), and the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) has issued a revised set of guidelines for England and Wales (2003). The recent revision of the SIGN guidelines brings the Scottish approach much closer to that in the rest of the country. The Scottish guidelines espouse the principle that the use of reliable predictors of brain injury is a preferable way to manage patients, rather than waiting to see which patients will reveal an intracranial bleed by their deteriorating condition. This emphasis is given practical meaning only because CT scanning is increasingly available to A&E departments. CT is very reliable for diagnosis of such injuries, even before the patient deteriorates, while skull X-ray can only give a clearer idea of level of risk. The NICE guidelines are based on Canadian head CT rule, which has isolated a group of factors which are clear indicators that head CT is required: the requirement for CT scan is equivalent to the concern that the patient has an intracranial bleed. In cases where the CT is not required, or where it is performed and there is no significant brain injury, the risk to the patient is small enough to discharge him with advice and social support.

Fracture of the skull is not the same as brain injury, but there are two considerations here. First, a patient who has suffered a skull fracture has been subjected to enough force to produce a brain injury. Second, there is a small incidence of serious, potentially fatal complications from fracture of the skull itself. An open skull fracture is a doorway for infection to enter the brain. An open, depressed skull fracture lodges a piece of bone and, possibly, other foreign matter in the brain and its protective tissues, with the risk of penetrating injury and cerebral abscess. Nevertheless, skull X-ray has no role in the management of head-injured patients, partly because a positive finding does not alter the treatment of many patients, and also because a CT scan is of much greater value in showing intracranial injury.

The Royal College of Radiologists (2007) cites skull X-rays as having a sensitivity of only 38% in detecting intracranial haematoma, while CT has close to 100%. However, CT carries a much higher radiation exposure. It is also the case that CT scanner availability remains a factor which may modify management in some parts of the country. A skull X-ray remains useful when there is a deep or large scalp wound but no other sign of an intracranial injury and it is desirable to exclude an open, depressed fracture before closing a wound. It can be used at a site which has no CT scanner to help a doctor to decide if the patient should be transferred for a scan. The Royal College of Radiologists (2007) following the guidelines issued by NICE has issued guidance on the indications for imaging of the skull.

The Royal College of Radiologists (2007) lists categories of head injury which offer low risk of intracranial injury. The patient has:

• Full orientation

• No amnesia

• No loss of consciousness

• No other clinical risk factors.

They recommend that such patients receive no X-ray or CT scan. They may be discharged with a sheet of head injury advice if they have someone responsible to look after them. An admission for observation may be considered if they have no one at home.

Among the signs which suggest a higher risk of intracranial injury are:

• GCS ≤12 at any time since injury

• GCS 13 or 14, 2 hours after the event

• Suspected open or depressed skull fracture

• Signs of base of skull fracture

• More than one episode of vomiting

• Post-traumatic seizure

• New or evolving focal neurology

• Age over 65 or coagulopathy in the presence of a history of amnesia, or reduced level of consciousness.

The management of patients with head injury should be guided by clinical assessments and protocols based on the Glasgow Coma Scale.

Indications for Immediate CT

• Eye opening to pain only or not conversing (GCS 12 or less).

• Confusion or drowsiness not improving in an hour of observation or two hours since injury.

• BOS/depressed fracture ± suspected penetrating injury.

• Reducing GCS or new focal neurology.

• Severe headache or 2 episodes vomiting.

• Coagulopathy with LOC, amnesia or neurology.

CT Within 8 Hours Age > 65 with LOC or amnesia

• Evidence of skull fracture but no need for immediate scan.

• Seizure.

• Retrograde amnesia > 30 mins.

• Dengerous mechanism or significant assault.

• If < GCS 15, all scans should include C spine.

(NICE Head Injury Guidelines 2003)

NICE Head Injury Guidelines 2003 are similar and recommend the following are also CT scanned:

• Amnesia of events >30mins before impact.

• Patients with any amnesia or LOC who also are over 65.

• Coagulopathy (hx of bleeding, clotting disorder, current treatment with warfarin).

• A dangerous mechanism of injury:

• pedestrian or cyclist hit by a car

• occupant ejected from a motor vehicle

• or a fall from >1m or 5 stairs.

A CT scan is indicated for these patients.

SIGN (2000) offers the following indications for admission to hospital after a head injury:

• Glasgow Coma Scale assessment of less than 15

• post-traumatic amnesia lasting at least 5 minutes

• post-traumatic seizure

• focal neurological deficit

• altered behaviour

• clinical or radiological evidence of skull fracture (which may include nose or ear discharge, full-thickness laceration, boggy haematoma and periorbital bruising) or penetrating injury

• severe headache or vomiting

• medical factors, such as anticoagulant use

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access