1. Midwifery, research and evidence-based practice

Key points

• Midwifery services are now provided within the context of evidence-based practice. This means midwives must avoid practices based on ritual and routine, and ensure that clear and acceptable evidence supports their clinical practice.

• Evidence-based practice is compatible with the philosophy of midwifery as it seeks to provide the highest and safest levels of care. It is an ethically and professionally defendable process.

• Working within a culture of evidence-based practice demands each midwife can demonstrate a range of skills, including an understanding key research concepts and principles, as well as skills in searching the literature, critiquing articles, and synthesising research into clinical guidelines.

• This book will provide an introduction to the knowledge and skills midwives need to play an appropriate role in the generation and application of research evidence to benefit those in contact with midwifery services.

The principle philosophy of health care in the UK, as with other major countries in the world, is evidence-based practice. In midwifery, this means a focus on clinical outcomes for women and their babies that are based on clear evidence of their effectiveness. Although this philosophy is well-matched with the philosophy of midwifery, it does demand increasing skills of the midwife. These include information searching, gathering and synthesising skills, and those of critical analysis. In particular, it is important that midwives, in common with other health practitioners, are research literate, that is, they have an understanding of the principles of research and how it can be evaluated. For some, it also means contributing to the generation of knowledge through research activity. This first chapter prepares the way for the remainder of the book by exploring the context of research in modern midwifery and identifies some essential skills for the individual midwife.

Although this is a book on research, we cannot start without firstly discussing evidence-based practice. This is because the goals and expectations of health care from a national right down to an individual level are shaped by the demands of evidence-based practice. Clearly this is a powerful concept that every health professional needs to understand, as it dominates so much of the thinking in health care. Its relevance to midwifery has been emphasised by Cluett (2005) who believes evidence-based practice is the linchpin to contemporary woman–centred maternity care. This first chapter, then, traces the development and meaning of evidence-based practice and its implications for an understanding of research within midwifery.

Three main players

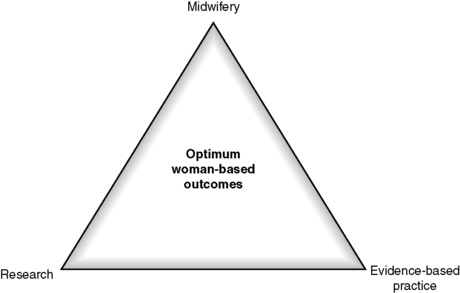

Published research is now a necessary and frequently accessed source of midwifery knowledge. This means that midwives need to be involved in carrying out research and know how to make use of research in their clinical practice. These two themes covering the production and use of research lie within the context of evidence-based maternity services and influence the structure of this book. For this reason, we now examine the relationship between the three main players of firstly midwifery, research and evidenced-based practice so that we can see the relationship between them.

Figure 1.1 demonstrates the interrelationship that exists between midwifery, evidence-based practice and research. Starting at the top of the triangle, we can argue that the goal of midwifery is to provide support and care to women and their families to ensure best outcomes; whether these are physical, emotional or social. In addition, the key principle in achieving this goal is that care should be woman-centred. The relationship between a mother and midwife can take many forms, as indicated in the following statement from The International Confederation of Midwives (2005):

|

| FIG 1.1 Providing optimum woman-based outcomes. |

The midwife is recognized as a responsible and accountable professional who works in partnership with women to give the necessary support, care, and advice during pregnancy, labour, and the postpartum period, to conduct births on the midwife’s own responsibility, and to provide care for the newborn and the infant. This care includes preventative measures, the promotion of normal birth, the detection of complications in mother and child, the accessing of medical care or other appropriate assistance, and the carrying out of emergency measures.

The midwife has an important task in health counselling and education, not only for the woman, but also within the family and the community. This work should involve antenatal education and preparation for parenthood and may extend to women’s health, sexual or reproductive health, and child care.

A midwife may practice in any setting including the home, community, hospitals, clinics, or health units.

Adopted by the International Confederation of Midwives Council meeting, 19th July, 2005, Brisbane, Australia.

This is a complex and extensive remit. To achieve a high standard of care throughout these activities and settings, clinical decisions must be based on the best available information. This is the role of evidence-based practice, which forms the next point at the base of the triangle. The term evidence-based practice is defined in this book as:

A problem-solving and decision-making system, based on the collection, evaluation and synthesis of sound evidence will ensure best practice by health professionals. This process should always be combined with professional judgement and the individual needs and desires of those receiving services.

The dominance of evidence-based practice in health care has led to it being seen as a ‘movement’ that has swept through so many countries and adopted as the preferred way of decision-making. This is illustrated in health policies and the activities of health organisations. A further definition of the process has been provided by Cleary-Holdforth and Leufer (2009: 286) as follows:

Evidence-based practice is an holistic approach to care delivery that places the individual patient at its core. It is far more than research utilisation alone and is a partnership between interprofessional clinicians, patients and the best available evidence to optimise patient outcomes

Although this definition talks about ‘patient’ rather than ‘woman’ it can easily be transferred to midwifery with its emphasis on a holistic approach to support each woman.

The whole system of basing care on evidence has been made easier through the improved availability and accessibility of research carried out in health care. This has created an increase in midwifery knowledge based on research carried out by midwives, obstetricians and social scientists. The result has the potential to create high standards of decision making in maternity care. The philosophy and practice of evidence-based practice provides the energy that encourages the use of research knowledge and unites the two corners at the base of the triangle in Figure 1.1 above.

The far corner of the triangle underpinning both midwifery, and evidence-based practice is research. We can define research as:

The systematic collection of information using carefully designed and controlled methods that answer a specific question objectively and as accurately as possible.

The result should be knowledge that increases our understanding of a topic or problem and which can be checked for accuracy. We should be able to apply this knowledge to a range of settings, not simply the one in which a study took place. In other words, research should be generalisable. This is one way in which quantitative research is judged: it should be capable of producing results that can be applied more generally (Polit and Beck 2008).

Evidence-based practice and research are not the same and should not be confused. Evidence-based practice focuses on the use or application of knowledge, usually that produced by research, in order to produce the highest standard of care and clinical outcomes. Research, on the other hand, is concerned with the production of knowledge that is as objective and accurate as possible. Evidence-based practice is the application of this knowledge as the foundation for clinical decision making. In this way, they can be seen as two distinct but related ingredients involved in the same process of improving midwifery care.

In summary, at the top of the triangle in Figure 1.1, evidence-based practice and research are used as tools as part of the practice of midwifery, to form the optimum clinical and care outcomes for a women and her baby, which forms the centre of the triangle. This model serves as a way of joining these different ideas in such a way that whichever point we choose to enter the model we can make sense of the way in which they are joined together and can see the bigger picture it represents.

Why evidence-based practice?

We can argue the compatibility of evidence-based practice and midwifery with the following passage from Leufer and Cleary-Holdforth (2009):

EBP [evidence-based practice] is highly relevant in a social and healthcare environment that has to deal with consumerism, budget cuts, accountability, rapidly advancing technology, demands for ever-increasing knowledge and litigation (p. 35).

This identifies many of the issues that confront midwifery care today and so provides motivation to embrace evidence-based practice as an integral part of maternity care. This point was made some time ago by Albers (2001) who was clear that the promotion of evidence-based care was consistent with the midwifery profession’s core value of woman-centred care. This means that although relatively new, evidence-based practice is not an additional or peripheral aspect of midwifery care but is part of providing care in the same way as it is accepted in nursing and other professional groups in health care.

In addition, using evidence for clinical decision making is part of an ethical obligation for all health professionals, as it demonstrates the responsibility to ‘do good’ as a result of professional action and ‘avoids doing harm’. In the language of ethical thinking, these are known as the obligations of beneficence (that is, doing good), and non-maleficence (that is, avoiding harm). This is supported by Roughley (2007) who suggests it is difficult to argue that midwives are in a position to guide women in decision making unless they have knowledge of the research that will enable women to make sound choices throughout pregnancy and the birth of their children. The professional duty to have up-to-date clinical knowledge is also reinforced through the following section in The Code (NMC 2008: 4):

• You must deliver care based on the best available evidence or best practice.

• You must ensure any advice you give is evidence based if you are suggesting healthcare products or services.

There are sound reasons, then, why midwifery has adopted the approach of evidence-based practice and all midwives are charged with supporting it. In the next section we will briefly consider the historical development of evidence-based practice so we can answer the question ‘how did we get here?’

The rise of evidence-based practice in health care

Within an incredibly short time period, evidence-based practice has become a global phenomenon, and is at the forefront of practice and health care provision in the UK (Dale 2005). According to Cullum et al. (2008), the term was first used in a publication in 1992 by Gordon Guyatt and the Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group where it was originally developed within the medical profession. It was introduced as a way of encouraging doctors to make use of the increasing amount of knowledge available through medical research to improve the standard of medical care. It was designed to replace tradition, intuition, or person preferences as the basis for decisions on patient investigations and treatments. The emphasis was on the ‘science’ of medicine rather than the ‘art’ of medicine.

The evidence-based movement spread rapidly from medicine to other health care groups including midwifery as an essential method of clinical decision making. Support for the approach swept through health policy and was the key message in the government report ‘The New NHS: Modern, Dependable’ (Department of Health 1997). The term ‘evidence-based practice’ is now common outside health care to include social work and areas such as evidence-based librarianship. This has led to it being promoted as a philosophy or way of thinking about professional decision making.

From recent beginnings, then, evidence-based practice has become a ‘taken-for-granted’ way of thinking about midwifery activity and in 2004 was said to be one of the most fashionable terms in health care (Rycroft-Malone et al. 2004). Despite this, the concept has been criticised on the grounds that it reduced the clinical freedom of practitioners to make their own decisions based on individual need and that it appeared to dismiss the experience of individual practitioners. In contrast, its supporters have argued there should be consistency and consensus in the way we carry out important clinical activities and these should reflect ‘best practice’, not the individual whims or preferences of the health professional. It has been argued that professional decisions should be influenced by objective or ‘scientific’ evidence that can be supported by well-conducted studies. This is because the evidence can be verified and demonstrated to be accurate. It is this aspect of being open to scrutiny by others and its accuracy tested that is not possible with individual experiences or opinions.

One implication of this move from experience to objective evidence has been that the ‘expert’ in the clinical area has moved from being someone with long or varied clinical experience, to someone who can find, evaluate and apply research findings to practice, and can integrate clinical standards or protocols into their own activities. This is a developing skill, as evidence is always changing and updating so protocols and guidelines need constant readjustment in line with latest evidence.

Developments within midwifery

Midwifery has long made use of best practice guidelines and has established midwifery research links to prestigious multidisciplinary research units. One notable example has been the work of midwifery researches within the National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit (NPEU) Oxford, in the UK. This research unit had been established by Ian Chalmers in 1978 with funding from the World Health Organization and the Department of Health, and consisted of a team of obstetric and midwifery researchers along with epidemiologists. Its work has included large research projects often with health policy implications, such as the Birthplace project, which was an integrated programme of research designed to compare clinical outcomes of 60 000 births planned in different settings such as home, different types of midwifery units, and in hospital obstetric units in England.

It was this unit that produced one of the early sources of midwifery evidence in the form of A Guide to Effective Care in Pregnancy and Childbirth (Enkin et al. 1989). According to Walsh (2010), the publication of this comprehensive summary of evidence allowed maternity care to move ahead of the game through the use of these guidelines based on randomised control trials. This was a paperback summary (without the references) of the two-volume, fully referenced version of Effective Care in Pregnancy and Childbirth (Chalmers et al. 1989) produced by the same team at the NPEU. The impetus to produce such a book had come following criticism from the influential British epidemiologist Archie Cochrane who had given obstetricians in the UK the ‘wooden spoon’ (loser’s prize) in 1979 for the clinical speciality that made the least use of available research evidence (King 2005). As a result of this, Chalmers, along with other members from the NPEU, took up the challenge by producing a guide to best practice in obstetric care.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access