Middle childhood and adolescence

Just the facts

Just the factsIn this chapter, you’ll learn:

physical, psychosocial, cognitive, and moral development of school-age children and adolescents

keys to health maintenance in middle childhood and adolescence

common concerns of school-age children and adolescents and their parents

injury prevention for school-age children and adolescents

common health problems during middle childhood and adolescence.

School age

School age, or middle childhood, refers to the stage of a child’s life from ages 6 to 12. The school-age years can be a spectacular journey filled with joys and successes as the child continues to grow and mature.

They can also be marked by challenges, as the child struggles to make sense of physical and psychological changes, his emerging identity, and the way he sees himself and is viewed by others (especially his peers).

|

Physical development

Physical growth at this time in a child’s life is relatively slow and smooth.

Height and weight

Growth slows considerably during middle childhood. During this stage, height increases an average of 2″ (5 cm) per year, and weight increases an average of 6 lb (2.5 kg) per year. However, during this time, the typical school-age child slims down and becomes more agile and graceful.

|

Ladies first

Girls tend to develop slightly faster than boys; although boys are, on average, taller and heavier than girls until the adolescent growth spurt.

Fine motor skills

By age 7, the brain has nearly completed its growth (at approximately 90%) and basic neuromuscular mechanisms are in place.

No more excuses

Development of small-muscle and eye-hand coordination increases, leading to the skilled handling of tools, such as pencils and papers for drawing and writing. The child can then spend the remainder of this period refining physical and motor skills and coordination.

Pubertal changes

The pubertal growth spurt begins in girls at about age 10 and in boys at about age 12.

|

Jumpin’ in feet first

Different areas of the body reach their peak growth at different times. Changes are easily recognized in the feet, which are the first part of the body to experience a growth spurt. Increased foot size is followed by a rapid increase in leg length and then trunk growth.

Leggy and hippy

During this time, leg growth increases more dramatically than trunk growth in boys. In addition, although girls have a greater growth spurt in hip width, boys exceed girls in other areas of bone growth.

No turning back

In addition to bones, gonadal hormone levels increase and cause the sexual organs to mature.

Preparation for menses

In girls, the first menstruation, called menarche, usually starts around age 12 but can occur as early as age 9 and still be considered normal. The menstrual cycle may be irregular at first.

Secondary sexual characteristics may start to develop— including breasts, hips, and pubic hair—and girls may experience a sudden increase in height. Nurses may find that this provides an excellent opportunity to educate school-age girls about breast self-examination and sexual responsibility.

Teeth

Loss of primary teeth and eruption of the first secondary teeth occur during the school-age years. Because of their size, secondary teeth may, for a while, appear disproportionately large in relation to the child’s other, smaller facial features.

Psychological development

Attending school marks an acceleration in the separation of the child from his parents. It introduces the child to a new set of authority figures (teachers, school administrators) and strengthens the concept of peer relationships.

Psychosocial development

The school-age child enters Erikson’s stage of industry versus inferiority. In this stage, the child wants to work and produce, accomplishing and achieving tasks. However, if too much is expected of him, or if he feels unable to measure up to set standards, the negative attributes of inadequacy and inferiority may prevail.

Language development and socialization

The school-age child has an efficient vocabulary and begins to correct previous mistakes in usage. He begins to understand the double meanings of words and becomes proficient at giving others directions without using physical signals.

Pick a clique

In the first and second grades, peers are increasingly significant to the child. His need to find his place within a group becomes important.

Handle with care: Sensitive to ridicule

The child’s world expands as interests and activities outside the home take on an expanded role in his life. He’s more independent, inside and outside the home. He understands the reasons for rules and becomes more sensitive to criticism and ridicule.

Play

The child’s personality has become structured, and he’s ready to be a partner in play with his friends. The child in this age-group typically has two to three best friends, who may change frequently. Most of his energies are devoted to school and his friends.

|

Cognitive development

School and learning are viewed by the school-age child as an exciting experience. The major developmental tasks at this time are achievement in school and acceptance by peers. Expectations in the classroom have intensified, and require concentration, attendance, and complex auditory and visual processing.

The school-age child is in Piaget’s concrete-operational period, a time in which the child uses thought processes to experience and understand events and actions. Children at this age are less egocentric and can see things from another’s point of view.

Try to remember

Reorganization of the frontal brain, which is used for selective attention, occurs between ages 5 and 7. The ability to reason and memorize improves, and the child tends to use mnemonic strategies to remember new information. In addition, the following occurs:

Magical thinking diminishes around this time, and the child has a much better understanding of cause and effect.

The child begins to accept rules but may not necessarily understand them.

Memory skills are continually improving, along with an increased attention span. The child is ready for basic reading, writing, and arithmetic.

Abstract thinking begins to develop during the middle elementary school years.

Parents remain very important during this time. Adult reassurance of the child’s competence and basic self-worth is essential.

Moral and spiritual development

In general, the first level of moral thinking is put into practice at the elementary school level, and the school-age child is in Kohlberg’s conventional level. The child behaves according to socially acceptable norms because an authority figure tells him to do so. This obedience is compelled by the threat of punishment (external factors).

“Because I said so”

At ages 11 to 12, as the child begins to approach adolescence, school and parental authority is questioned and, occasionally, even challenged or opposed. The importance of the peer group intensifies, and rough, bold, or even brazen behavior becomes increasingly common. The peer group becomes the source of behavior standards and models.

Mom’s still the bomb

Parental guidance, love, and support are absolutely essential for the development of values during this time. The child at this age needs the opportunity to make decisions within defined boundaries. Ideally, those boundaries are set by responsible adults in the child’s life.

Earth-bound

Spiritual lessons should be taught in concrete terms during this stage. Children have a hard time understanding supernatural religious symbols. Repeated religious rituals, such as praying and attending church services, may comfort them.

When it comes to teaching children about being healthy, tell parents to remember these things to care for their PEDS:

Proper nutrition

Exercise

Dental hygiene

Sleep.

Keys to health

During the school-age years, the child’s understanding of cause and effect, coupled with his need for parental (and peer) approval, provides an excellent opportunity to continue teaching about the need to make healthy lifestyle choices. Parents should continue to teach their children about the importance of:

proper nutrition

sleep and rest

exercise

dental hygiene.

Nutrition

Children should be encouraged to eat a variety of healthy foods, such as lean meats, fruits, vegetables, and grains, to ensure proper nutritional intake.

Developing healthy eating habits

Encouraging healthy eating habits now (during school age and, ideally, before) will lay a stable foundation for adolescence, when caloric needs increase. Childhood obesity is increasing, and measures should be taken to avoid high-fat, high-sugar, low-protein foods. (See Encouraging proper nutrition.)

It’s all relative

It’s all relativeEncouraging proper nutrition

To ensure that children continue to develop and maintain healthy eating habits, encourage parents to:

stock the pantry and refrigerator with healthy choices for afterschool snacks (raw vegetables, low-fat yogurts, fresh fruits)

avoid taking children to fast-food establishments where high-fat foods are abundant

teach children how to read nutrition labels while shopping at the grocery store

involve children in planning and preparing meals for the family

offer candy and other sweets as an infrequent privilege rather than a reward for good behavior

change their own eating habits to model good dietary habits for their children.

Sleep and rest

Requirements for sleep and rest are unique and relate to the child’s activity level and physical health. School-age children generally don’t require an afternoon nap, and compliance at bedtime becomes easier. Children should develop healthy sleep habits by not having a television in their bedrooms.

Things that go bump in the night

Sleepwalking and sleeptalking may begin during this stage, and parents should take measures to ensure the child’s physical safety during these episodes. Nightmares are usually related to a real event in the child’s life and can usually be eradicated by resolving any underlying fears the child might have.

Exercise and activity

Exercise and other forms of physical activity should be encouraged to help the child begin healthy habits for a lifetime. Doing so may also prevent childhood obesity.

Children who are interested in sports should be encouraged to join sport teams or participate in sporting events. Sport teams and events are usually same-sex events at this age level, making them less intimidating. Those who aren’t interested in team sports and whose family are unable to meet the time or financial demands should be encouraged to participate in regular family play, walks, or bike rides. Children should learn the importance of daily activity, and parents should limit sedentary activities such as playing video games.

Clicking the remote doesn’t count

Parents should encourage physical exercise after school instead of more sedentary activities such as watching television or playing video games.

Dental hygiene

During the school-age years:

Teeth should be brushed at least twice a day and, if possible, after meals.

Drinking water should contain fluoride or fluoride supplements should be given.

Flossing should be taught, and parents should monitor for method and compliance until the child is 8 years old.

Regular dental cleanings should be scheduled every 6 months.

Coping with concerns

During school age, the child’s life revolves around home and family, school, and peers. School-age children (and their parents) are commonly faced with concerns about school and after-school supervision.

School phobias

School phobias may also be called school refusal or school avoidance. A child’s refusal to go to school may be a sign of a separation anxiety, which occurs in families that are particularly close and caring or in a child who relies heavily on the support of his family. It may also occur after a particular trauma, such as the death of a pet, illness within the family, or a move to a new school.

In these cases, the child may be more fearful of leaving home than he is of going to school. He may, for example, be afraid that something bad will happen to a parent, sibling, or pet if he isn’t there to protect them.

Scary school

Refusal to go to school may also be related to fear of the school itself and what the child experiences there. Parents should talk to their child and try to determine the underlying cause of his fear. Possible reasons for school phobias include:

being the target of a bully

anxiety about academic achievement

having problems adapting to the school structure.

|

Stealing

Stealing is attractive to the younger school-age child who simply wants items for himself. The child has a limited sense of what belongs to someone else and will commonly lie to cover up the offense.

Low on dough

A sense of responsibility for one’s actions begins to take shape at the end of middle childhood. Stealing at the end of middle childhood is commonly a sign that something is lacking in that child’s life. Possible causes include a lack of:

financial means

attention from a parent or caregiver

sense of property rights.

What’s yours is mine

Parents should recognize the child’s property rights and offer some privacy in this regard, when possible. A child who knows that his own property is respected is more likely to understand the importance of respecting the property of others.

Adolescence

Adolescence is defined as the developmental stage between ages 13 and 19.

Physical development

Adolescence is a time of change. As physical changes occur, adolescents struggle with the conflict between asserting their independence and still relying on their parents.

Terrible teens

Many adults view the changes that occur during adolescence with great fear and trepidation. Although not always the case, it may be a turbulent time for the adolescent and his parents.

|

Height and weight

During this time, a teenager’s weight almost doubles and his height increases by 15% to 20%. Girls may grow 3″ to 6″ (7.5 to 15 cm) per year until age 16. Boys may grow 3″ to 6″ per year until age 18. Major organs double in size; the exception is the lymphoid tissue, which decreases in mass.

Boys attain greater strength and muscle mass, but motor coordination lags behind growth in stature and musculature. Motor coordination catches up as strength improves.

Development of secondary sex characteristics

The pituitary gland is stimulated at puberty to produce androgen steroids responsible for secondary sex characteristics. (See Beginning sexual maturity in girls and Beginning sexual maturity in boys, page 133.)

It’s a girl thing

Female secondary sexual development during puberty involves increases in the size of the ovaries, uterus, vagina, labia, and breasts. The first visible sign of sexual maturity is the appearance of breast buds. Body hair appears in the pubic area and under the arms, and menarche occurs. The ovaries, present at birth, remain inactive until puberty.

Growing pains

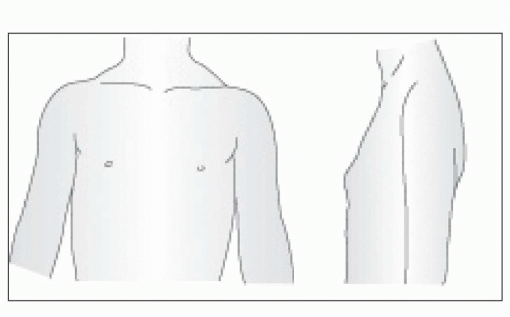

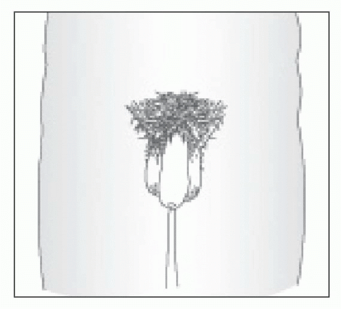

Growing painsBeginning sexual maturity in girls

Breast development and pubic hair growth are the first signs of sexual maturity in girls. These illustrations show the development of the female breast and pubic hair in puberty.

Breast development

Stage 1

Only the papilla (nipple) elevates (not shown).

Stage 2

Breast buds appear; the areola is slightly widened and appears as a small mound.

|

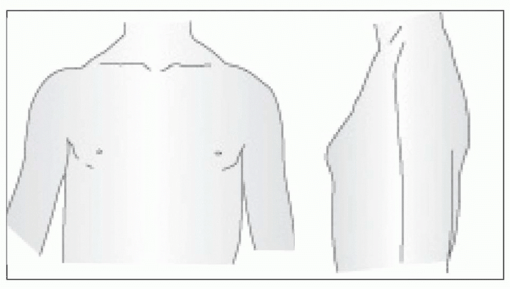

Stage 3

The entire breast enlarges; the nipple doesn’t protrude.

|

Stage 4

The breast enlarges; the nipple and the papilla protrude and appear as a secondary mound.

|

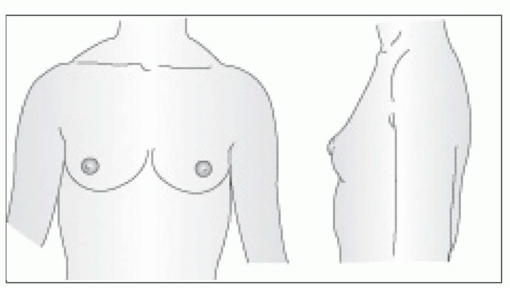

Stage 5

The adult breast has developed; the nipple protrudes and the areola no longer appears separate from the breast.

|

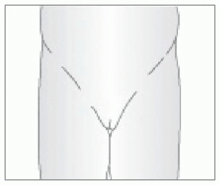

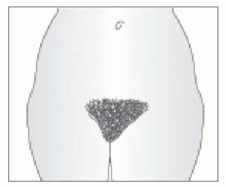

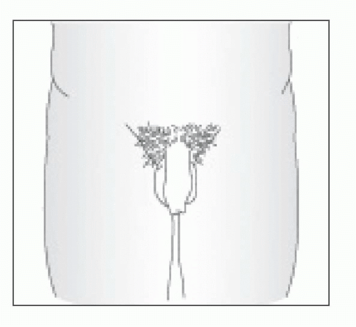

Pubic hair development

Stage 1

No pubic hair is present.

|

Stage 2

Straight hair begins to appear on the labia and extends between stages 2 and 3.

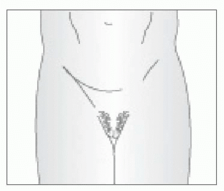

|

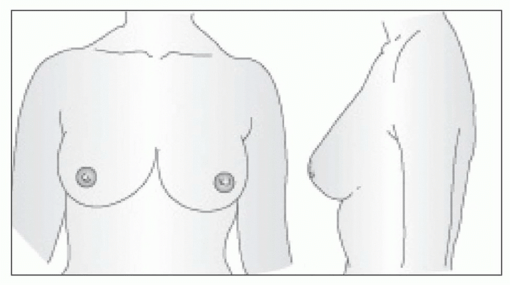

Stage 3

Pubic hair increases in quantity; it appears darker, curled, and more dense and begins to form the typical (but smaller in quantity) female triangle.

|

Stage 4

Pubic hair is more dense and curled; it’s more adult in distribution but less abundant than in an adult.

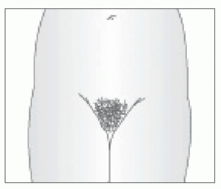

|

Stage 5

Pubic hair is abundant, appears in an adult female pattern, and may extend onto the medial part of the thighs.

|

Growing pains

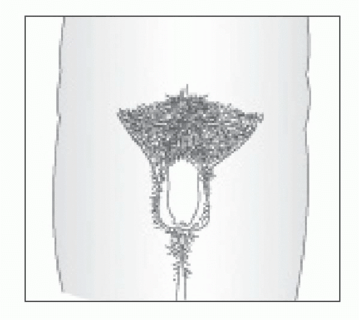

Growing painsBeginning sexual maturity in boys

Genital development and pubic hair growth are the first signs of sexual maturity in boys. The illustrations below show the development of the male genitalia and pubic hair in puberty.

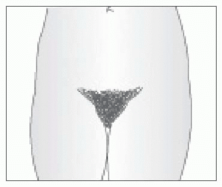

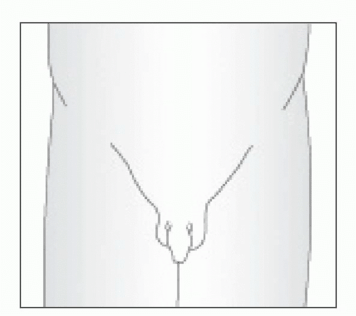

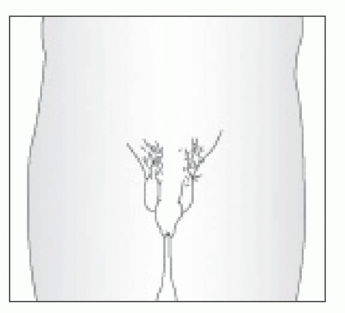

Stage 1

No pubic hair is present.

|

Stage 2

Downy hair develops laterally and later becomes dark; the scrotum becomes more textured, and the penis and testes may become larger.

|

Stage 3

Pubic hair extends across the pubis; the scrotum and testes are larger; the penis enlarges in length.

|

Stage 4

Pubic hair becomes more abundant and curls, and the genitalia resemble those of adults; the glans penis has become larger and broader, and the scrotum becomes darker.

|

Stage 5

Pubic hair resembles an adult’s in quality and pattern, and the hair extends to the inner borders of the thighs; the testes and scrotum are adult in size.

|

Boys will be boys … until they’re men

Male secondary sexual development consists of genital growth and the appearance of pubic and body hair.

Androgens and estrogens

The trigger that starts puberty is unknown. What’s clear is that, for some reason, the hypothalamus produces gonadotropin-releasing hormone, which triggers the anterior pituitary gland to produce follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH). FSH and LH initiate the ovulation cycle in girls and promote testicular maturation and sperm production in boys.

Tanner staging

The development of secondary sex characteristics occurs in an anticipated sequence for girls and boys, and is divided into distinct stages, called Tanner stages. Although the timing of the stages is different for each individual, the sequence remains the same.

Menstruation and spermatogenesis

During early adolescence (ages 11 to 14), most girls achieve menarche. Most boys achieve active spermatogenesis at ages 12 to 15.

Teeth

The secondary (permanent) teeth are all present during the early adolescent years. The four third molars (also called wisdom teeth) may need to be extracted if impaction occurs.

Psychological development

Psychological development during adolescence revolves around socialization. As the teen ventures into the world outside his own family and is exposed to other viewpoints, peers become increasingly important and independence is tested.

Psychosocial development

Adolescence is the period of identity development, according to Erikson, as the child enters the stage of identity versus role confusion. Changes in the adolescent’s body are taking place rapidly, and he’s preoccupied with how he looks and with how others

view him. While trying to meet the expectations of his peers, he’s also trying to establish his own identity.

view him. While trying to meet the expectations of his peers, he’s also trying to establish his own identity.

Early adolescence

During early adolescence, the teen begins to show more interest in the opposite sex, although the peer group usually consists of same-sex friends.

That’s what friends are for

Friends become much more important, and interest in family and family activities decreases.

Rebel with a question

Conformity to peer group standards is of utmost importance at this time. This may lead to rebellion and questioning of parental (and other adult) authority.

Middle adolescence

The teen becomes more self-assured during middle adolescence, and independent decision-making skills are tested.

The young and the tasteless

Activities outside the home take on even greater importance, and the teenager commonly defines himself by whatever the peer group has defined. He wears what other teens in his group wear, he speaks using the common language the peer group has decided on, and his taste in music and other preferences go along with the crowd.

|

When girls no longer have cooties

It’s at this time that relationships with the opposite sex are established.

Late adolescence

During the late teen years, adolescent rebellion has diminished. The young adult has a fairly strong sense of who he is but may not yet have committed to a particular occupation or role in life.

Cognitive development

During adolescence, the teen moves from the concrete thinking of childhood into Piaget’s stage of formal operational thought. The teen can now reason logically about abstract concepts and derive conclusions from hypothetical premises.

I can see clearly now …

He can imagine events in the future instead of focusing on the present (as in childhood). Because the future becomes a possibility, the teen may be more receptive to education that focuses on health promotion and can concentrate on future benefits as a result of current behaviors.

|

One step forward, two steps back

Although abstract thinking becomes more refined, the teen may revert back into concrete thinking during times of stress.

Moral and spiritual development

Kohlberg’s conventional level of moral development continues into early adolescence. At this level, the child does what’s right because it’s the socially acceptable action. At this level, the child continues to advance in moral reasoning as his cognition develops.

In with the in-crowd

The teen becomes increasingly dependent on his peer group for approval and associates good behavior with “fitting in” with the crowd. Morality may be dependent on the situation and relationship. Commonly, peer pressure will override the teen’s own moral reasoning.

At long last—my own person

As adolescence ends, the teen enters Kohlberg’s postconventional, or principled, level of moral development. He starts to question and discard status quo, and chooses values for himself, not necessarily what’s dictated by his peers. Although he may appreciate the peer group’s opinions, he’s now capable of forming a moral decision independent of the group.

|

What’s the meaning of life?

The teen formulates questions about the larger world as he considers religion, philosophy, and the values held by parents, friends, and others. Adolescents are suspicious about parental religious views, and curiosity about other religious beliefs is normal. They sort through and adopt those religious beliefs that are consistent with their moral character.

Look, Mom, I’m legal!

Their worldview becomes solidified during this time. The teen may be considered a young adult and societal laws reinforce this. By age 18, he’s allowed to vote, and by age 21, he’s considered a full adult with all of the rights and responsibilities that go along with

that status. Even so, the adolescent remains somewhat dependent on his parents for finances and for help in meeting the adult responsibilities given to him.

that status. Even so, the adolescent remains somewhat dependent on his parents for finances and for help in meeting the adult responsibilities given to him.

Keys to health

Health issues during adolescence include nutrition, sleep and rest, exercise, and dental hygiene.

|

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access