Web Resource 8.1: Pre-Test Questions

Before starting this chapter, it is recommended that you visit the accompanying website and complete the pre-test questions. This will help you to identify any gaps in your knowledge and reinforce the elements that you already know.

Learning outcome

By the end of this chapter, the reader should be able to:

- Define the term ‘health improvement’

- Critically analyse the health improvement policies

- Analyse the education/practice gap

- Describe the difference between a convergent and divergent mentor

Health Improvement

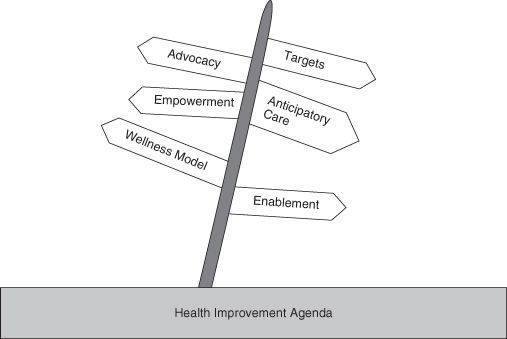

Healthcare has evolved from a sickness service to a health improvement service, where the emphasis is on anticipatory care, where self-care is promoted and with a shift away from hospital services to community-based care provision. Health improvement is an expression that has superseded the term health promotion. Health promotion is seen as the means of improving individual and community health at an individual level. Public health is seen as organised social and political effort and includes health promotion that benefits populations, families and individuals (Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety, Northern Ireland and Department of Health and Children 2005). According to Tannahill (2008) health improvement is an umbrella term that aims to provide a sustained enhancement of positive health, with a consequential decline in ill health. The ‘top-down’ approach to this delivery is via policies, strategies and activities which overlap in the following areas:

- Social, economic, environmental and cultural elements

- Equity and diversity

- Education and learning

- Services, amenities and products

- A ‘bottom-up’ approach that is community led and community based.

Web Resource 8.2: PowerPoint Presentation on Health Improvement

Web Resource 8.2: PowerPoint Presentation on Health Improvement

Visit the accompanying website to view a PowerPoint presentation that will provide further information and clarification of the term ‘health improvement’.

Health Improvement Policies

Following devolution in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, health policies have differed in the four countries of the UK as each tries to produce policies that reflect their various needs. As health is a devolved issue different government departments in the four countries are now responsible for the development, implementation and evaluation of these health issues. In England the responsibility lies with the Department of Health, in Scotland liability lies with the Scottish Government Health Department, in Wales accountability is with the Welsh Assembly Health and Social Care, whereas in Northern Ireland it is the role of the Northern Ireland Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety.

Recent changes in the UK government have led to major political differences between the right wing, conservative government in Westminster and devolved left wing government in Scotland and Wales.

Although there is a general spirit of partnership to collectively address issues that have an effect on the health of the entire population of the UK, such as inequalities, for example, each of the four countries has slightly different priorities. As the governing parties within the devolved nations do not necessarily have the same political perspective as the Westminster government, this too leads to differences in both priorities and policy content. The policies of the four countries are, however, unanimous in recognising the importance that health improvement plays in advancing the population’s wellbeing (Table 8.1).

Table 8.1 Policies, principles and values held by the four UK health systems

| Countries | Policies | Principles and values |

| England | Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS (2010) A stronger local voice (2006) |

|

| Scotland | Mutual NHS and Bill of Rights 2008 Transforming public services. The Next Stage of reform (2007) |

|

| Wales | One Wales 2007 Sign Posts – A Practical Guide to Public and Patient Involvement in Wales (2001) |

|

| Northern Ireland | A Healthier Future (2008) sets out a vision for health- and social care in Northern Ireland over the next 20 years From Vision to Action, strengthening the Nursing Contribution to Public Health (2003) |

|

The documents provided in Policies column can be found via the web links at the end of the chapter.

These policies have contributed to significant advances that are apparent in the health of the populations, demonstrated by the fact that people are living longer and experiencing compression of morbidity. Compression of morbidity is when there is a postponement of diseases normally associated with the ageing process. When the chronic diseases occur the person dies faster as a result of being frail. This in itself defines a shift in the health profiles of the UK population and creates additional pressure on the NHS, which will have to be addressed in future healthcare planning and delivery.

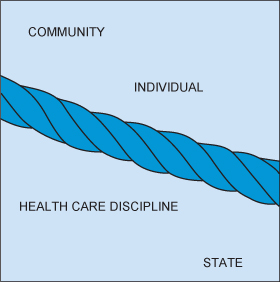

Partnership Working

Health education policies across the UK generally emphasise the significance of partnership working with individuals, communities, healthcare disciplines and the state (Department of Health or DH 2004). Since the inception of the NHS there has been a constant tension in the balance of power held by these partners, with an acknowledgement that early on in the development of the NHS the balance was predominantly weighted towards the state. This was exhibited as top-down management of individuals and communities with health being very much ‘done to’ the population (DH 2004). In more recent times there had been a significant shift in the balance of this power away from what might be viewed as the ‘nanny’ state and towards the empowerment of individuals and communities themselves, as significant contributors to the public health of these nations (Welsh Assembly 2009). This centre–left political philosophy is known as the ‘third way’.

Web Resource 8.3: PowerPoint Presentation on the ‘Third Way’

Web Resource 8.3: PowerPoint Presentation on the ‘Third Way’

Visit the accompanying website to view a PowerPoint presentation that will provide further information and clarification of the term ‘third way’.

Tension between Partnerships

All four UK countries acknowledge partnership as being vital to the engagement of the population in taking forward their public health and health improvement agendas. There is an increased responsibility placed on individuals and communities to make healthy choices among the available options, for healthcare disciplines to ensure that they provide and signpost healthy choices and information, and for the state to ensure equal opportunities to access these choices by narrowing the gap between health inequalities (DH 2005).

This particular perspective on delivering health promotion and improvement is based on a number of assumptions:

- All partners will behave as expected and be willing and able to make these choices once they have the correct information.

- There will be no hindrances to these parties in their move towards being healthy.

- All parties have the ability to deliver the expected targets of the health improvement policies.

These assumptions are predominantly paternalistic, because they presume that people, if left to their own devices will make mistakes, these mistakes will be bad for their welfare and that this justifies preventing or minimising them making these choices (Wilkinson 2009).

The first assumption, that all partners will behave as expected, assumes that individuals will be willing to make healthy choices when faced with a bewildering array of options and that communities will support these healthy choices and the individuals who opt for them. As the article in Case study 8.1 demonstrates, this is not always the case.

Case study 8.1 Improving school meals

Jamie Oliver, the celebrated chef, persuaded the government to part with £220 million to improve school dinners. However, he failed to impress two mothers who instead of backing his mission to introduce healthier meals started running a fast food delivery service offering fish and chips, hamburgers and fizzy drinks.

The mums began the service for youngsters because they said children were not interested in the overpriced ‘low-fat rubbish’ being served at lunchtimes. Healthy eating campaigners and council chiefs called for an immediate end to the business, claiming that the pair were undermining the battle to cut teenage obesity. The mothers, however, insisted that children should be given a choice to eat what they wanted.

One mum said ‘We go up at break time and take down the orders through the school fence. We then go back at 1pm to deliver the food and give them their change. The demand is incredible. We are now delivering around 50 to 60 meals a day and we have no intention of stopping.’

The fast food campaign began when the children returned to school from the summer holidays and were told that they could not leave the premises at lunchtime, preventing them from getting food from the local takeaways. The mothers claimed that the children didn’t enjoy the school food and as a result they were left starving. The prices for school dinners, they claimed, were ridiculous. ‘My son had a school meal deal and was charged £3.75 for a small piece of pizza, a milkshake and a piece of fruit’. She insisted that her children ate a balanced diet at home, adding: ‘I prepare a meal every night and we have a varied diet’. One mum, whose 11-year-old son also goes to the school, said: ‘This is all down to Jamie Oliver. He is forcing our kids to become more picky about food. Who does he think he is being all high and mighty? He can feed whatever he wants to his kids, but he should realise that other parents think differently.’

A spokesman for Jamie Oliver said: ‘If these mums want to effectively shorten the lives of their kids and others kids, then that’s down to them.’

‘If parents are struggling to afford a school meal then they should make the effort to construct a proper lunchbox with fruit and veg, dairy, bread, protein which can be done for under £1.20, instead of taking the lazy option and going down to the takeaway.’

Adapted from Sims (2006) by J. Thompson.

Issues Raised by this Article

The issue of healthy eating raises a number of opposing views and personal judgements: the mother accuses Jamie Oliver of being ‘high and mighty’ and the spokesperson for Jamie Oliver accuses the mothers involved of being ‘lazy’.

Questions:

- Why do you think the issue of healthy eating raises so much anger?

- What are the views of those involved?

- What implication has this incident for future health promotion campaigns?

- What should healthcare professionals do differently when they are instigating health promotion activities with in a community?

Different perspectives: from a parent’s perspective – the role of a parent is a difficult one, especially in areas of deprivation, during financial hardship and at particular key points within a child’s life, such as their teenage years. Many parents feel that the state (education, health and welfare) criticises their choices, attacks their parenting skills and undervalues them as parents. Any deviation from what is deemed ‘healthy’ by the state, due to lack of money, education or power, reflects badly on them. These criticisms are seen to come from groups or individuals who have no understanding or experience of deprivation.

The state’s perspective: alternatively, the state who have to prioritise finite resources to enable health to be paramount in their decisions often feel that those who do not act on health messages are lazy, ignorant and lack willpower. These opposing views frequently create a misunderstanding of lifestyle choices and an underestimation of the factors that relate to healthy choices. If health were really all about education, willpower and resources then well-educated, well-resourced individuals would not have obesity problem.

The implications for this may be well known to healthcare professionals, but this also must challenge the values and judgements that they themselves carry in respect of this issue.

Consider: your own values as a healthcare professional, as an individual and as a member of your community. Do these values conflict in any way? If so, how might you resolve them?

Although this article highlights the problem of obesity in England, by visiting the websites for the Scottish Parliament, the National Public Health Service for Wales and the Health Promotion Agency for Northern Ireland Executive, you will see that they to demonstrate a range of initiatives being utilised to tackle obesity.

In terms of health and welfare this article raises the question of responsibility. The World Health Organization (WHO) and the government label obesity as a problem. Policies are developed, targets set, implemented and evaluated in order to address obesity. For those who do not heed the warnings, obesity continues to be a problem for them and their children.

What emerges is that policies are informed by popular beliefs and values as well as scientific evidence which are balanced with cost-effectiveness. The policy agenda is not static, consistent or consensual, but constantly shifts and evolves.

The welfare state arose in the first half of the twentieth century and led to pensions, welfare handouts and nationalisation of medicines. This was based on the notion that the country is better off when the population is healthy. Today the population believes that it has a right to access these provisions freely and is appalled if private care is seen as an alternative. A problem arises, however, when the government is seen as having an obligation to its citizens because the possibilities for entitlements then become endless.

Consider this

As the government pays for welfare state provisions, should it be able to order individuals not to smoke, drink, take drugs, eat fatty foods? If people do not comply, should health and financial benefits be withdrawn? Issues similar to these are happening!

Web Resource 8.4: PowerPoint Presentation on ‘The Frayed Safety Net’

Web Resource 8.4: PowerPoint Presentation on ‘The Frayed Safety Net’

Visit the accompanying website and view the PowerPoint on the ‘Frayed Safety Net’.

Individuals do not always have the ability to choose healthy options. This is particularly true in respect to giving up smoking, healthy eating and taking exercise.

The naïve view that it is just a case of willpower does not take account of the myriad of complexities of day-to-day living. This view serves only to make individuals feel less empowered and more a victim of their circumstances. Society targets certain groups in this way, e.g. those who are obese. It has been suggested (Vision of Britain 2020 – visit www.visionsofbritain2020.co.uk/research/health-wellbeing/paying-for-the-nhs and Chapter 3, Executives summary, to read the vision) that people with bad diets and who do not take enough exercise should be penalised if they are deemed unwilling to change their lifestyles. This view demonstrates that medical model and behaviouralist approaches still persist.

Web Resource 8.5: Case Studies

Web Resource 8.5: Case Studies

To consider these issues further view the two case studies on the accomanying web page.

Activity 8.1

Over the next few days, look and listen for newspaper articles and radio debates on health-related issues. Then consider the following questions:

- Who is raising the issue and whom do they represent?

- Is the issue on the political agenda, nationally or internationally?

- Where is pressure being directed?

- Having located the article in the press and topic on the government website, compare the two pieces of information and identify any differences between the government rationale for the issue with how the media deals with the issue

- What values are being expressed through this issue?

- Do these values fit with the principles of the NHS?

Principles of the NHS:

- Healthcare should be provided according to people’s needs rather than their ability to pay. It should be free at the point of delivery to ensure that people seek help when they need it

- Healthcare should be collectively financed from general taxation

- Healthcare should be comprehensive to cover the whole range of people’s health needs in one centrally planned service

- Healthcare should be universal and equally available to all sectors of the population and in all areas of the country

- The NHS should be concerned with reducing inequalities in health

Visit the appropriate government health website. Click on the health topic related to the issue and then track the related policy. Consider the likely impact of this policy on the issue being raised.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree