4 Mental health practice learning

• To gain an understanding of the nature of various mental health practice areas

• To identify the possible learning opportunities which will enable you to optimise your placement experience and meet your Nursing and Midwifery Council competencies and essential skills clusters

• To consider the views of students and mentors who have experience of working within the practice area

• To develop skills in action planning for placements in order to direct your experience in line with your learning needs

Introduction

The NHS next-stage review outlined a new direction for the configuration of health and social care services promoting increased integration and partnership, requiring health professionals to work across service boundaries (Darzi 2008). In the future, healthcare services will be required to meet a number of challenges including an ageing population, the delivery of care in different environments and rapidly changing technology (Longley et al 2007). In order to help nurses of the

1. Identify what approach to practice learning is used in your university.

2. Identify what ‘type’ of practice settings you might be going to on your course.

3. Consider what you already know about these settings and what you might need to know to help you plan your learning for these areas (Ch. 5 will help you with this).

4. Check the chapter aims and outcomes for Section 2 and highlight the chapters you feel will be most relevant.

5. Write an action plan for how you will find out any further information you need about the practice areas where you will be on placement.

future meet some of the challenges, the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) stipulates that practice learning for students undertaking pre-registration education must reflect the service users’ journey in order to support the practitioners of the future to work in reconfigured service structures (NMC 2010).

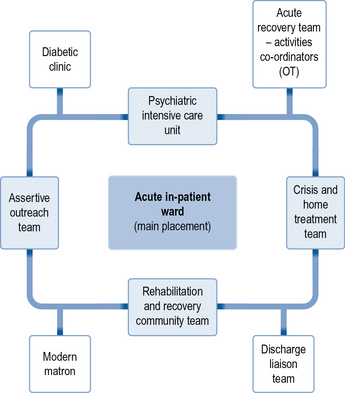

In some courses this pathways approach will mean you are based in one practice area for longer, spending a few weeks during this time in practice areas that link with this service. This might also include shorter insight visits where you may have the opportunity to spend time with different professionals or in settings outside health care (such as the coroner’s court). Figure 4.1 shows what this might look like. The centre box represents the main placement area, the lightly shaded boxes may be the practice areas where you could spend a few weeks and the unshaded boxes may be where you link with for insight visits. Depending on your course, this could be arranged for you, or it may be something that you have the opportunity to get involved in arranging yourself following discussion with your mentor.

Routes into mental health services

GPs remain one of the main gatekeepers to mental health services and, in many respects, GP surgeries are a major provider of mental health support. However, GPs refer to both primary and secondary mental health services (there will be some local variations in the design of these services). Counselling and psychotherapy services are delivered by mental health nurses and specially trained mental health workers in GP surgeries. These practitioners provide support for individuals with common mental health problems or who may be experiencing trauma and can gain psychological input for their experiences on a short-term basis. GPs will refer directly to these practitioners. They may also refer people on to community mental health teams of which there are a number of different types (see Ch. 6). The circumstances and diagnosis of each individual may define where they are referred. Here, professionals working in the community (commonly mental health nurses) will conduct an assessment to decide whether they are the appropriate people to provide support. For people who are highly distressed and in immediate need, GPs can also refer directly to a crisis and home treatment team. This service can provide short-term and intensive support to the individual in his or her own home until the crisis period is over. They can also work towards securing an admission to hospital for the individual if this is required.

Care delivery environments

In-patient placements

• Service users are perceived as needing assessment and treatment in a contained setting rather than the service user’s home environment.

• The Mental Health Act (1983) may be used at some point during the service user’s assessment and treatment.

• Interaction with, and interventions by, a range of mental health professionals is a given.

• The potential for disturbance, annoyance, irritation and aggression from other service users is ever present.

• Opportunities for copycat behaviour and infection by other service users’ pathologies are increased.

• Lack of continuity and consistency is an inevitable consequence of the shift systems used in many institutional care settings.

• Activities of daily living such as sleeping, eating, activity and so on may be compromised for most service users in some way.

• The contained environment is needed to facilitate, primarily, safety and security for the service user. In most instances the reason to assess and treat someone in a hospital environment rather than in their own home means that they are too distressed or disturbed at the time of assessment to be helped in their own home. It is likely, therefore, that the student will see service users being admitted and treated who are often clearly more distressed or disturbed than can be seen in community settings.

• The use of the Mental Health Act (1983) inevitably produces tension between healthcare workers and service users who are being subjected to detention or treatment orders. The ways that experienced and effective professionals strive to maintain therapeutic relationships with service users, despite often being the implementers of the law, can provide rich learning opportunities.

• Institutional healthcare settings, by definition, are sustained by other institutional systems. For example, a typical mental health ward will be serviced by social workers, psychiatrists, occupational therapists, psychologists, phlebotomists, pharmacists, clerks, domestics and so on. The effective mental health nurse must sustain a constructive working relationship with all of these different visitors, in order to provide the best possible service to the client group. As the nurse does this, she provides a role model for the observant student, as well as evidence that the job of a qualified mental health nurse involves skills such as diplomacy, assertiveness and so on, as much as knowledge of medications and Mental Health Act Sections.

Mental health placement learning areas

Adult community mental health care services

The following section will provide information from students and mentors on these services with a focus on what you should know before commencing the placement, a description of what you might experience and hints and tips on how to make the most of the learning opportunities. Further descriptions of services can be found at the Mind Website (http://www.mind.org.uk).

Placement 1: Crisis intervention and home treatment team: a student experience

Placement 2: Adult community mental health teams (CMHTs)

Rosie Robinson, third-year mental health branch student nurse

Within Melissa and Denise’s narratives there may be some roles, definitions or language that you have not heard before. Use the jargon and acronyms buster in Appendices 1 and 2 to identify what these terms mean in a mental health context.

professions such as psychologists, occupational therapists, social workers and psychiatrists. This includes multidisciplinary meetings in which you can participate. I had the opportunity to develop my confidence in administering depot medication. The key learning opportunity for me was that you have the chance to visit people in their own homes and support their carers. I also got much more comfortable with using the Care Programme Approach paperwork, including notes, assessment documentation and care plans along with participating in initial assessments.

I hope you enjoy your community time as much as I did and have a great experience!

Placement 3: Early intervention team

Placement 4: Assertive outreach team

Amy Ramful, third-year mental health branch student nurse

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree