CHAPTER 5 Mental Health Disorders

The most prevalent mental health problems encountered in school settings are discussed in this chapter. Along withChapter 6, Substance Abuse, these chapters provide a broad overview of the psychiatric disorders of childhood and adolescence. Mental health disorders have an impact on cognition, behavior, emotions, and social functioning. This can occur directly through neurological mechanisms affecting domains such as attention, cognitive processing, and impulse control, and it can occur indirectly through psychosocial areas such as self-esteem, motivation, emotional regulation, and peer relationships. Disabilities in any of these areas can affect the school performance and school life of a child or adolescent. Current brain research provides data regarding the areas of the brain involved and the impact these disorders may have on learning.

ATTENTION DEFICIT-HYPERACTIVITY DISORDER

Box 5-1 DSM-IV Criteria: Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

Based on these criteria, three types of ADHD are identified:

From American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, ed 4 text revision, Washington, DC, 2000, American Psychiatric Association.

Brain Findings

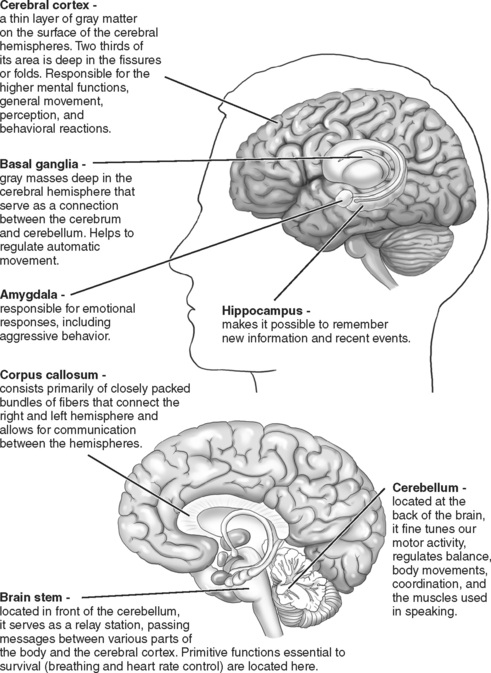

ADHD is believed to have a neurological basis. Research has found evidence of a chemical imbalance or irregularity in certain neurotransmitters, especially dopamine and norepinephrine, consistent with the genetic results described in the previous section. PET studies have demonstrated hypometabolism of glucose (Pary et al, 2002) in particular areas of the brain thought to be involved in attention. When a student is challenged with academic problems, such as math, the typical brain fires up the frontal lobe and starts working; the brain of the student with ADHD does not. With correct stimulant medication, dopaminergic activity increases in the brain, and the student is able to work on the assigned task or class problem.

National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) brain-scan studies indicate the volume of matter in several key parts of the brain is 3% to 4% smaller in children with ADHD who have never been on medication. The areas, compared in the sample and controls, include the cerebrum, cerebellum, gray and white matter for the four major lobes, and the caudate nucleus, a part of the basal ganglia. These key parts of the brain, except for the caudate, appear to stay on a parallel developmental path during childhood and adolescence in patients and controls. This suggests that genetic and early environmental effects on brain development are unchanging and not related to medication (Castellanos, 2002). Furthermore, the decreased brain volume may be a factor in some biological processes, which can manifest as hyperactivity or impulsiveness in the educational setting (Bower, 2002).

Researchers also found a smaller volume of white matter in children with ADHD who had never been on medication compared to the control group. Another study found an enlarged hippocampus in children and adolescents with ADHD compared to the control group. This study supports the hypothesis that the pathophysiology of ADHD involves the limbic system and limbic-prefrontal circuits (Plessen et al, 2006).

V. Health Concerns and Emergencies

OPPOSITIONAL DEFIANT DISORDER

Brain Findings

Studies suggest the neurotransmitters dopamine, serotonin, and noradrenaline play a role in ODD with the most significant impact caused by noradrenaline (Kariyawasam et al, 2002; Comings et al, 2000).

Cortisol levels have been found to be low in children with ODD. Children taking stimulant medication for ODD have increased levels of cortisol (Kariyawasam et al, 2002; Snoek, 2004). Conclusions of the research indicate that cortisol responsivity during stress is different in these children and may manifest in how aggressive children respond to stress (McBurnett, 2002).

V. Health Concerns and Emergencies

PERVASIVE DEVELOPMENTAL DISORDERS

AUTISM

Box 5-2 DSM-IV Criteria: Autistic Disorder

A. Total of six or more items from 1, 2, and 3, with at least two from 1 and one each from 2 and 3:

B. Delays or abnormal functioning in at least one of the following areas with onset before age 3 years:

C. The disturbance is not better accounted for by Rett syndrome or childhood disintegrative disorder.

D. The disturbance is not better accounted for by another specific pervasive developmental disorder or by schizophrenia.

From American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, ed 4 text revision, Washington, DC, 2000, American Psychiatric Association.

Table 5-2 Early Risk Indicators for Autism

| Age | Behavior |

|---|---|

| Under age 12 mos | |

| 12 mos. | |

| 16 mos. | No single words. |

| 23 mos. | No two-word spontaneous phrases. |

| Any age | Loss of language or social skills at any age. |

Brain Findings

Results from postmortem and imaging studies have implicated many major structures of the brain in autistic disorders, including cerebellum, corpus callosum, basal ganglia, brainstem, and portions of the limbic system (see Figure 5-1). Unusually high levels of specific proteins associated with brain development have been reported in children with autism (Nelson et al, 2001), and parts of the frontal lobe are thicker than normal; this region controls decision making and planning. Other research suggests that the mirror neuronal system involved in understanding another person’s actions is impaired in those with autism (Schumann and Amaral, 2006). This may result in loss of empathy and language skills, as well as the ability to learn by imitative skills. Neurons in the limbic system where emotions are processed are plentiful but are one third fewer in number than normal.

FIGURE 5-1 Major brain structures implicated in autism.

Redrawn from Strock M: Autism spectrum disorders, pervasive developmental disorders (NIH Pub No NIH-04-5511), National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute of Health, US Dept of Health and Human Services, Bethesda, Md, 2004 (available online): www.nimh.nih.gov/publicat/autism.cfm.

Another biological theory is that autism may be caused by faulty wiring in the brain, or underconnectivity, that makes it inefficient (Grossberg and Seidman, 2006; National Institutes of Health, 2004). The cerebellum’s ability to assist in making predictions of ensuing thoughts, emotions, and motor movements appears to be affected. Several studies have documented abnormalities in the Purkinje cells essential to the wiring of the cerebellum, including a significant decrease in their size and number (Fatemi et al, 2002; Kern, 2003). These cells inhibit the action of other neurons. Furthermore, the male autistic brain has fewer neurons in the amygdala compared to males without the disorder. Whether this occurs at birth or later as a degenerative process is unknown (Schumann and Amaral, 2006).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree