Chapter 45 MENTAL HEALTH

Perhaps the most important aspect of understanding mental illness is being able to define the difference between mental illness and mental health. This first section aims to help nurses gain an understanding of mental health and mental illness and the factors that impact on both.

CONCEPTS OF MENTAL HEALTH AND MENTAL ILLNESS

WHAT IS MENTAL HEALTH?

The concept of mental health is difficult to define, as mental health is much more complex than merely the absence of a mental illness. There are numerous definitions of what constitutes mental health. It has been defined as a state in which people are able to cope with, and adjust to, the recurrent stresses of everyday living in an acceptable way (Watkins 2001). It has also been defined as a satisfactory adjustment to one’s life stage and situation (Ebersole & Hess 2001), and it has been defined as relating to feelings of happiness, contentment and personal satisfaction with life’s achievements, as well as with feelings of optimism and hope (Fontaine & Fletcher 1999; Stuart & Laraia 2001). For most people the feelings associated with mental health will be present sometimes and not others and will vary in intensity at different times. According to this view, then, mental health is a state that can change frequently and that can fluctuate according to specific circumstances. Ebersole & Hess (1985) capture the concept of fluctuation in this definition:

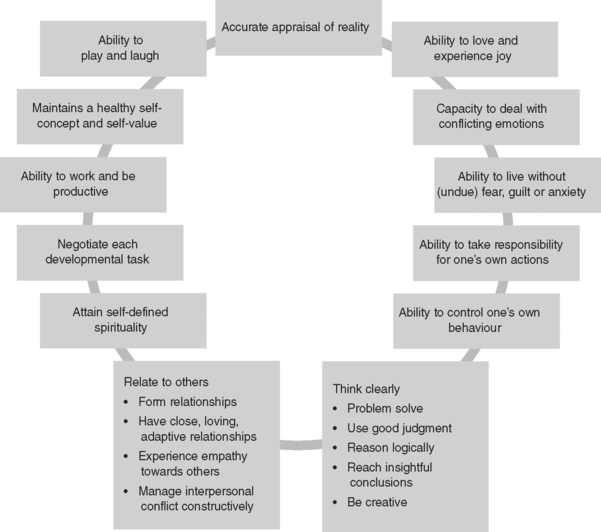

Figure 45.1 illustrates some of the characteristics of mental health.

DEVELOPMENT OF MENTAL HEALTH

According to Shives (2005) the factors that influence the development of mental health relate to three main areas: inherited characteristics, nurturing during childhood and life circumstances.

Nurturing during childhood

Nurturing during childhood relates primarily to the relationships that develop between children, their parents and their siblings. It is thought that positive relationships, those that promote feelings of being loved, secure and accepted, facilitate the development of children into mature and mentally healthy adults. It is thought that negative relationships may result when children experience maternal deprivation, parental rejection, serious sibling rivalry and early communication failures, are more likely to result in a poor sense of self-worth and a lower level of mental health (Shives 2005). The quest for a sense of self begins in childhood; children who have positive nurturing experiences are more likely to have a stronger sense of identity than those who have negative nurturing experiences (Watkins 2001).

Life circumstances

Life experiences can influence mental health from birth onwards. Positive life experiences include pleasurable times and success at school and with friends, a good job, financial security and good physical health. Negative experiences include poverty, poor physical health, unemployment and unsuccessful personal relationships (Shives 2005).

Different people will react to childhood experiences and life circumstances in different ways. Some, despite negative circumstances, will develop positive strategies for coping and will not become mentally ill. Generally it is people who have not achieved a strong sense of identity who are more prone to mental illness (Watkins 2001). Perhaps this is most clearly understood when considering the mental health of Indigenous populations. It is not difficult to imagine how the effects of colonisation, the removal of children from their families, the loss of traditional lifestyle and cultural practices and the resulting social disruption may impact negatively on mental wellbeing. It is generally understood that the difficulties involved in belonging and adjusting to two different cultural contexts can make it difficult to establish a strong sense of identity. The difficulties faced by Indigenous people have led to some serious mental health concerns. For example, there are worrying levels of depression, substance misuse, self-harm, harm to others and suicide in Aboriginal people in Australia that are at higher rates than in the non-Indigenous population (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS] and Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW] 2003).

Nurses working with Indigenous people can better empathise and not negatively judge behavioural signs of mental ill-health if they recognise that it often stems from deep mental anguish and spiritual sorrow relating to the effects of European invasion (Brown 2001).

WHAT IS MENTAL ILLNESS?

What society considers is normal

People tend to evaluate the behaviour of others based on their own social, cultural, ethical and behavioural standards. Therefore, behaviour that is regarded by one person as acceptable and normal may be perceived by another person as totally unacceptable. In addition, what is accepted as normal in a society may change over time. For example, homosexuality was at one time considered a diagnosable clinical mental disorder (Stevens 2001). When a person’s behaviour is in question it is appropriate to ask ‘Who is qualified to decide whether this behaviour is acceptable or not?’ and ‘What is the meaning and relevance of this behaviour in relation to the context in which it is occurring and to the person’s society, religion and culture?’

In every society and cultural group there are different interpretations of certain behaviours and events. For example, in Western psychiatric terms, visual or auditory hallucination (people seeing or hearing things that no one else does) are viewed as abnormal and a sign of mental illness, whereas in some cultures these happenings are viewed as experiences of symbolic and spiritual importance and those experiencing them may be revered as visionaries as opposed to being perceived as mentally ill (Varcarolis 2006; Fontaine & Fletcher 1999).

A matter of degree

Anxiety, fear, anger, sadness and the need to be alone are feelings commonly identified in mental illness but they are normal feelings experienced at different levels of intensity by most people at various times. Depending on the intensity of the emotions, people may not feel as mentally healthy as they do at other times but will not necessarily be classified as mentally ill. It is when the feelings are exaggerated and extend over longer periods of time than deemed normal that the person is likely to seek professional help and be diagnosed as having a mental illness. For example, a diagnosis of a depressive disorder is likely when sadness or feelings of being ‘down in the dumps’ become deep, long-lasting feelings of despair that the person cannot escape from without professional help. Mental illness or mental disorder are therefore terms used to designate changes from normal mental functioning that are sufficient to become, and be diagnosed as, a clinical disorder (Weir & Oei 1996). Broadly, mental illness can be defined as a state in which an individual exhibits disturbances of emotions, thinking and/or action, but it can be defined in a multitude of ways. Clinical Interest Box 45.1 provides a range of definitions of mental illness.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 45.1 Definitions of mental illness

There is no clear line that divides mental health from mental illness; the two grade into one another. Table 45.1 provides some areas of comparison between the two but it should be noted that, while these are general traits that mentally healthy or mentally ill people tend to share, different types of mental illness manifest with different effects and with different levels of intensity. In addition, mentally healthy people may experience more than one type of mental dysfunction at different periods in their lives.

TABLE 45.1 AREAS OF COMPARISON BETWEEN MENTAL HEALTH AND MENTAL ILLNESS*

| Attribute | The mentally healthy person | The mentally ill person |

|---|---|---|

| Self-concept | Poor self-image, low sense of self-worth and unable to recognise talents, so cannot achieve personal potential | |

| Relationships | Able to form close, meaningful and lasting relationships. Can communicate emotions and can give and receive | Inability to cope with stress can result in disruption, disorganisation, inappropriate responses and unacceptable behaviour that make it difficult to meet the expectations of others in work or social environments. This means that there may be an inability to establish or maintain meaningful relationships. These factors may result in a limited social support network |

| Outlook on life | Optimistic and positive view, sense of purpose and satisfaction | Tends to a pessimistic negative view of present and future |

| Coping and adaptation | Able to tolerate stress and return to normal functioning after stressful events. Can cope with feelings such as frustration and aggression without becoming overwhelmed | Can feel overwhelmed by even minor levels of stress and may react with maladaptive behaviour |

| Judgment/decision making | Uses sound judgment to make decisions and is able to problem solve | May display poor judgment and avoid problems rather than attempting to solve them |

| Characteristics/traits | Can delay gratification | May feel an urgency to have personal wants and needs met immediately and may demand immediate gratification |

| Level of functioning | May act irresponsibly, be unable to accept responsibility for own actions and may blame others for outcomes | |

| Perceptions | Able to differentiate between what is imagined and what is real because can test assumptions by considered thought. Can change perceptions in light of new information | May be unable to perceive reality |

* It should be noted that these are general points only. Different types of mental illness manifest with different effects and, while there are traits that mentally healthy people tend to share, many mentally healthy people may experience several areas of dysfunction at different periods in their lives. Mental illness may occur as a temporary inability to cope; it may occur episodically with long periods of mental health in between; or it may occur as a chronic condition that is constantly present.

(Shives 2005; Stuart & Laraia 2001; Varcarolis 2006)

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF MENTAL ILLNESS

Symptoms of mental illness include changes in personal habits, social withdrawal and changes in mood and thinking. While particular symptoms occur with specific disorders, there are warning signs that indicate the presence of a mental health problem. Clinical Interest Box 45.2 provides examples of early warning symptoms of mental illness that may occur in children, adolescents and adults. (For details concerning the symptoms associated with specific disorders, refer to texts dedicated to mental health or psychiatric nursing such as those listed at the end of this chapter.)

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 45.2 Warning signs and symptoms of mental illness

In younger children

In older children and adolescents

WHO IS MOST AT RISK OF DEVELOPING A MENTAL ILLNESS?

Anyone can develop a mental illness but some groups of people in society are particularly at risk. Clinical Interest Box 45.3 identifies groups of people at greater risk of mental illness.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 45.3 People at risk of mental illness

Anyone can develop a mental illness, but people at particular risk include:

Many people from all age groups and of different social, educational and cultural backgrounds cope with highly stressful events and accumulative stressors. (Factors relating to the ability to cope with stress are described and discussed in Chapter 13.)

CLASSIFICATION OF MENTAL DISORDERS

There are more than 200 classified forms of mental illness. These include:

MEDICAL DIAGNOSES

The American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is a respected and influential classification system under which a mental illness is determined according to the symptoms experienced and the clinical features of the illness. There are many categories of classification but mental illness is mainly classified within the following areas:

NURSING DIAGNOSES

Mental health nurses develop nursing diagnoses in response to the client’s experience, emotions and behaviours. Nursing care responds holistically to the client’s biological, psycho-social, spiritual and environmental needs and specifically addresses the client’s feelings and behavioural responses to those feelings, many of which are common across several different medically classified conditions. Examples of some nursing diagnoses commonly used in mental health nursing are provided in Clinical Interest Box 45.4.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 45.4 Examples of nursing diagnoses used in mental health nursing

Although the use of the terms psychosis and neurosis to describe particular illnesses is no longer favoured, nurses need to be aware of the meanings associated with each as the terms are still used in some contexts. The terms are out of favour because symptoms ascribed to each condition can occur in the other, and this causes confusion. The term psychosis refers to disorders that are so marked and incapacitating that the person who is afflicted is out of touch with reality and lacks insight into the illness and the associated behaviours, which may be unusual or bizarre. Psychosis was the term traditionally used to describe disorders such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, in which the symptoms experienced were quite different to those experienced by other people and included delusions and hallucinations (Gibb & Macpherson 2000). (Clinical Interest Box 45.5 provides explanations and examples of delusions and hallucinations.)

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 45.5 Delusions and hallucinations**

| Type | Example |

|---|---|

| Somatic delusions (a false belief involving a body part or function) | A young woman believes her body is rotting away from the inside, her heart is made of ice and is gradually melting because she doesn’t deserve to live |

| Nihilistic delusions (false feeling that the self, others or the world is non-existent) | A client refuses to eat, saying there is no need for him to eat because he has no body |

| Delusions of persecution (oversuspiciousness: the person falsely believes themself to be the object of harassment) | A client believes the staff belong to a cult, are watching his every move and are out to get him. He is afraid to go to sleep for fear of what the staff might do to him |

| Delusions of control (false belief that one is being controlled by an external source) | A client believes her feelings, thoughts and actions are being controlled by aliens who send messages to her via the television, instructing her on what to do |

| Delusions of grandeur (exaggerated beliefs about personal importance or powers) | A client believes he is God and controls the universe |

| Delusions of self-depreciation (beliefs of unworthiness) | A client believes she is ugly and sinful, saying, ‘I don’t deserve to be loved — look at me — it shows that I am full of sin’ |

| Type | Example |

|---|---|

| Visual hallucination | A client tells you that he sees his deceased wife in different areas of his home |

| Auditory hallucination | A 16-year-old client tells you she hears voices in her head saying derogatory things such as, ‘You are worthless, you don’t deserve to live’ |

| Gustatory (taste) hallucination | A middle-aged client with organic brain syndrome complains of a constant metallic taste in his mouth |

| Olfactory hallucination | A 30-year-old client states that she smells ‘rottenrotten garbage’ in her bedroom although no one else can smell anything unusual or unpleasant |

| Tactile hallucination | A middle-aged woman undergoing symptoms of alcohol withdrawal reports feeling ants crawling all over her body although no ants are present |

* Clients can experience delusions and hallucinations together. For example, a client may hear her dead daughter’s voice, see her standing close by and be convinced that she caused her daughter’s death despite of evidence to the contrary that her daughter died as a result of injuries received in a car accident when on holiday with a friend.

(Shives 2005; Fortinash & Holoday Worret 2003)

Unlike people suffering from a psychotic disorder, those with what used to be termed a neurosis have insight into their condition. For example, a person who has an obsessive-compulsive disorder may experience persistent and intrusive thoughts (obsessions) about personal cleanliness. To decrease the level of anxiety the person may wash his hands hundreds of times a day, even if his hands become red and raw (compulsion to act). When they are extreme, such thoughts and acts may be so unusual and disrupt the person’s life to the degree that to the observer the person is mentally ill. Unlike those experiencing a psychotic disorder, the affected person is aware that the behaviour is abnormal (there is insight into the behaviour and the illness). Despite their condition, people who have what was once classified as a neurosis can often continue to function in society, whereas a person who is psychotic cannot function effectively (Gibb & Macpherson 2000).

THEORETICAL MODELS AND CAUSATION OF MENTAL ILLNESS

Historically the medical profession was prominent in the care of people with mental illness and as a result there has been, and still is, a strong focus on identifying physical causes of mental illness. However, others have looked at psychological, sociocultural, interpersonal and human development factors and there are now many theoretical models used to explain the presence of a mental disorder. Mental health nurses select concepts from the various relevant models that best explain the client’s behaviours, problems and needs. They then draw on these concepts as a basis for client assessment and then for planning, conducting and evaluating care (Varcarolis 2006). The following provide very basic examples of a small selection of theoretical models. To work effectively in the area of mental health, however, nurses need a deep and sound understanding of a wide range of models.

THE MEDICAL, OR BIOLOGICAL, MODEL

This model explains mental illness as being caused by physiological malfunction in the body. Physical causes can be separated into acquired and non-acquired factors. Acquired causes include head injury, cerebral infection and substance misuse. Non-acquired causes include genetic transmission, electrical conductivity changes in the brain, or alterations to the production and/or activity of neurotransmitters (Gibb & Macpherson 2000). There is evidence to support biological explanations. For example, studies indicate that depression and schizophrenia may be linked to abnormal neurotransmitter function, and that genetic factors may be linked to both (Kennedy & Mitzeliotis 1999; Varcarolis 2006). A medical approach to treating mental illness tends to focus primarily on medication and sometimes includes electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), both of which aim to correct chemical imbalance in the body believed to be caused by abnormal neurotransmitter function in the brain. Emil Kraepelin (1856–1926) is a theorist associated with the origins of the medical model.

PSYCHOLOGICAL AND PSYCHODYNAMIC MODELS

The psychoanalytical model, first conceptualised by Sigmund Freud (1856–1939), is possibly the most well-known model in this group. Freud’s model viewed human personality as developing predominantly within the first 5 years of life and focused mostly on unconscious, non-rational and instinctual parts of human behaviour (Varcarolis 2006). Freud attributed disrupted behaviour in the adult to developmental tasks that were not accomplished successfully at earlier developmental stages. For example, within this theoretical framework a mental illness may be linked to a failure during adolescence to move successfully from dependence on parents to independence. Freud’s mode of treatment was psychoanalysis, which aimed to bring unconscious problems to conscious awareness.

Carl Jung (1875–1961), Melanie Klein (1882–1960) and Erik Erikson (1902–1994) are some of the theorists that have expanded on Freud’s thinking about the nature of human development and behaviour. Erikson’s theory has provided nurses with a developmental model that encompasses the entire life span. Erikson studied healthy personalities and focused on human strengths as well as weaknesses, emphasising how people who failed to achieve developmental milestones at various life stages could rectify these failures at later stages (Varcarolis 2006).

It was Freud who identified the manner in which humans develop and used defence mechanisms to ward off anxiety that might otherwise be overwhelming and incapacitating (Varcarolis 2006). Defence mechanisms prevent conscious awareness of threatening feelings and can be a helpful response in adapting to stress, but their overuse can be a sign of maladaptation to stress and an indicator of mental ill-health. They are particularly relevant in understanding stress-vulnerability and stress-adaptation models of health and illness. Stress-vulnerability/adaptation models recognise that throughout life there is a need for everyone to adapt to change, for example, to adjust to school and then work life, to living with a partner, or to becoming a parent or a grandparent and then to retirement and perhaps the death of a spouse. The model views that some people find it more difficult than others to adapt to life’s changes and to cope effectively with the stressors that change can bring. When life results in a stressful situation or there is an accumulation of multiple stressors, people who have been unable to develop and establish adequate coping skills and coping resources are at the highest risk of developing a mental illness. (See Chapter 13 for further information concerning these two theoretical models, the use of defence mechanisms and adaptation to stress.)

SOCIAL AND INTERPERSONAL MODELS

Social/interpersonal models draw attention to the impact of factors within a person’s social environment on mental wellbeing. The basic concept is that negative social factors such as low status, low levels of support, isolation and poverty contribute to and increase the risk of developing mental illness such as depression (Gibb & Macpherson 2000).

COGNITIVE BEHAVIOUR MODELS

Cognitive behaviour models stem from the assumption that behavioural responses are learned. Ivan Pavlov (1849–1936) developed the understanding of learned behaviours when he found that when a bell was repeatedly rung each time dogs were given food the dogs began to salivate just at the sound of the bell. This conditioned reflex was termed classic conditioning and is acknowledged as a form of learning that applies to humans, learning in which a previously neutral stimulus comes to elicit a given response through association. For example behavioural theorists would suggest that children who observe parents responding to every minor stress with anxiety would soon learn the response and would develop a similar pattern of behaviour (Stuart & Laraia 2001). According to the behavioural model, this early learning experience would be considered a significant factor in the cause of an anxiety disorder and limited constructive coping strategies in later life.

BF Skinner (1904–1990) added to behavioural theory by introducing the concept of operant conditioning. Operant conditioning refers to the use of reinforcers to motivate the repetition of particular behaviours. The use of positive reinforcement (the continual rewarding of desired behaviours) forms the basis of behaviour modification therapy used to help motivate clients to change undesirable behaviours. It has been effective for clients with phobias, alcohol addiction and a variety of other conditions (Varcarolis 2006).

Aaron Beck was one of the early founders of cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT), now a common and often very successful form of psychological treatment. It is based on the view that dysfunctional behaviour is linked to dysfunctional thinking, and that thinking processes are shaped by underlying beliefs. For example, the client with depression believes, ‘I am no good at anything, I’m worthless, and nobody likes me’. Cognitive behaviour therapy is based on helping clients recognise, challenge and change dysfunctional thinking. (Chapter 13 provides further information about CBT.) Beck’s work has primarily focused on helping people with depression but he has expanded the use of CBT to include working with people who have complex disorders such as borderline personality disorder and schizophrenia, and there are distinct signs of success (Fenichel 2000).

THE PROVISION OF CARE

THE MULTIDISCIPLINARY TEAM

Many people may be involved in assisting a person who is experiencing a disruption or potential disruption to their mental health. Mental health care commonly employs an interdisciplinary team approach to care management. The client’s care, according to individual needs, is planned and implemented by a team composed of mental health nurses, psychiatric social workers, counsellors, clinical psychologists, general or specialist medical officers (depending on the client’s physical status) and pharmacists. Additional team members may be required and, depending on individual needs, these may include: a dietitian; an occupational therapist; a recreational, art, music or dance therapist; complementary health care therapist; and a chaplain or other spiritual support person (Clinical Interest Box 45.6).

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 45.6 Some members of the health care team

It should never be forgotten that the most important member of the team is the client, and often clients know what they need to promote their own recovery. Some clients have reflected on the times when they have been at their most vulnerable. For example, some clients who have experienced admissions to acute-care settings have identified that what they need most at times of severe mental distress is somewhere they can feel safe and supported, somewhere they can relax and calm down, and someone to be with them who will listen and really hear them (Watkins 2001). While the client may feel the need for medication, it is not appropriate or helpful to implement other therapeutic interventions, such as group therapy, recreational therapy or family therapy, until the client is feeling less distressed and can collaborate in decisions about what sort of interventions will be most helpful. Skilled helping involves actively listening to the client and working collaboratively with the client to achieve a process of recovery. (See Chapter 29 for information concerning active listening as a therapeutic measure.) The therapeutic process involves health professionals, including nurses, as facilitators who use their knowledge to help the client become more resourceful and self-reliant. This helping relationship needs to be a participative but never a directive process (Watkins 2001). The model of helping relationships established by Carl Rogers (1961) and the model of skilled helping established by Gerard Egan (1994) are client-centred models of caring on which many mental health nurses can reliably base their therapeutic interactions with clients.

RESPONSIBILITIES OF THE MENTAL HEALTH NURSE

Mental health nursing may be described as an interpersonal process in which the nurse uses the presence of self, interpersonal communication skills and a knowledge of physiology, psychology and sociology to help clients in mental distress. A combined understanding of biological processes and psychodynamic processes is essential for the mental health nurse because many people with mental illness have a concurrent physical problem, and the two are often interconnected (Stuart 2001a).

Nursing care aims to help clients cope with the experience of mental illness, prevent relapse and to promote a return to mental health through a successful rehabilitation program. The primary aims of mental health nursing (Watkins 2001) are to help individual clients to:

FACILITATING DEVELOPMENT OF CONSTRUCTIVE COPING MECHANISMS

While the nurse’s role in stress and stress management is explained in Chapter 13, some specific points need to be highlighted here. To recognise and deal with stress, individuals need to be provided with information about, and helped to recognise:

There is a wide variety of activities that clients may find helpful in promoting coping, but there is no one right or best activity. What works for one person may not work for another. Nurses have a responsibility to provide clients with information and options, but only the client can know what feels appropriate, so the choice of what activities to attempt or to become involved with should ultimately rest with the client. Clinical Interest Box 45.7 provides examples of positive constructive coping strategies, coping resources and negative destructive coping mechanisms.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 45.7 Examples of positive constructive coping strategies, coping resources and negative destructive coping mechanisms

THE NURSE’S ROLE IN EDUCATING THE PUBLIC AND REDUCING STIGMA

One particularly important facet of the community mental health nurse’s role is educating the public about mental illness to reduce the stigma that for many mentally ill people is the biggest hurdle to overcome (Watkins 2001). There is a general lack of knowledge in the community about what constitutes mental illness and about the prognoses of mental disorders, which ensures that mental illnesses are often surrounded by mystery, misinformation and stigma (Weir & Oei 1996). Despite positive interventions in recent years, people suffering from mental illness remain among the most stigmatised, discriminated against, marginalised, disadvantaged and vulnerable members of society (Johnstone 2001). Clinical Interest Box 45.8 illustrates one person’s experience of stigma.

Several myths about mental illness create fear of those affected and this fear serves to increase stigmatising behaviours and attitudes. For example, there is a widely held perception that people with mental illness are often out of control, unpredictable and may pose a threat. The truth is that most people with mental illness do not behave in this way; however, severe mental distress is often highlighted in the media, and this links images of dangerous behaviour with mental illness in the minds of the public (Watkins 2001). In addition, single, isolated and often very minor criminal acts committed by mentally ill people tend to be sensationalised by the media, contributing to negative stereotypes (Jewell & Posner 1996).

The lack of accurate knowledge about mental illness that leads to fear, mistrust and sometimes violence against people living with mental illness and their families can also serve to:

The picture is not always as dismal as this. Many mental health care users are themselves excellent ambassadors for people with mental illness. By calling themselves consumers or clients they have empowered themselves to become advocates for other people experiencing mental health disorders. Mental health care users or consumers now have a vital role to play in participating and planning the delivery of mental health services (Happell & Roper 2003). Consumer advocacy groups now exist in every state and territory of Australia to promote participation of consumers in planning, implementation and evaluation of mental health services. Accordingly, many consumers live and work within a local community, use the same facilities (e.g. shops, library, cinema, sports centres) as everyone else, are accepted by the people within the community and experience no harassment and attract no hostility from the local residents (Repper et al 1997). All nurses can play a part in highlighting and reducing stigma by:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree