12

Medicines management in the community

• To give an overview of the activities involved in medicines management and the role of patients and practitioners

• To explain the importance of medicines management in the community and primary care

• To illustrate the impact of good medicines management on the quality of care using case studies

• To identify the student’s role in medicines management in the community and identify opportunities for learning

Introduction

Medicines make a huge impact on the health and wellbeing of individuals and populations. They enable people to: live longer; help prevent the onset and adverse effects of acute illness; effectively manage long-term conditions; prevent and treat infection and promote health. Not surprisingly, medicines are the most common clinical intervention used in the NHS today (National Prescribing Centre 2008). However, there are also significant costs associated with medicines. There are human costs, resulting from unwanted side-effects or the inappropriate use of medicines, which can lead to serious illness or death. There are also huge financial costs for the health service in paying the medicines bill, which includes medicines that are dispensed and never used. As life expectancy increases and new treatments enter the market, the medicines bill will continue to rise.

Medicines management can be described as:

Medicines management aims to enable people to get the maximum benefit from the medicines they take, not only by ensuring that they are appropriate and clinically effective but also by balancing safety, cost, tolerability and choice. The term covers a wide range of activities involving doctors, pharmacists, nurses, other members of the health and care team and most importantly, the person and their family. However, the nursing team plays such a pivotal role, that medicine management has been included in the NMC Standards for Pre-registration Nursing Education as one of the five Essential Skills Clusters (ESC) (NMC 2010), Consequently, medicines management underpins a number of your nursing programme learning outcomes.

Medicines management in the community

• Promoting partnerships with patients and carers to improve medicines adherence

• Educating health and care practitioners

• Monitoring and evaluating the desired and undesired effects of medication through medication review

• Reporting suspected adverse drug reactions

• Safe storage and disposal of medicines.

Why is medicines management so important?

Safety, effectiveness and cost underpin medicines management. Medicines aim to control symptoms, help improve a person’s health and wellbeing and prevent ill-health of individuals and populations, for example through immunisation programmes. However, we know that people do not always use medicines in the way that was intended by the prescriber. NICE (2009) have estimated that up to 50% of patients do not take their medicines as prescribed. Sometimes, people choose not to take their medicines at all. They may be unclear about their purpose or they may have a physical or psychological problem which prevents them from following the directions they have been given. As a result, far from getting benefit from the medicine, people continue to experience poor health or may be affected by the harmful effects of taking medicines incorrectly. This has a huge personal cost to the individual and family. There is also a cost to the health service, as money wasted in one part of the health service means denying services in other areas.

An adverse drug incident refers to an unsuitable or incorrect procedure. The National Patient Safety Agency (2009) identified three incident types accounting for 71% of the serious harm or fatal outcome of medication incidents. These were:

Four groups of drugs account for more than 50% of the drug groups associated with preventable drug-related hospital admissions: antithrombotics (e.g. aspirin); anticoagulants (e.g. warfarin); non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g. ibuprofen); and diuretics (e.g. hydrochlorothiazide) (Howard et al 2007).

Garfield et al (2009) reviewed the UK literature and found a prescribing error rate of around 7.5% and showed that approximately one in 15 hospital admissions were related to medication, with two-thirds of these being preventable. Barber et al (2009) reviewed the medication of older people living in 55 care homes in England and found that 70% of the residents they studied had one or more medication error.

An adverse drug reaction (ADR) is defined on the MHRA website as:

Pirmohamed et al (2004) studied hospital admissions in the UK and found that:

How people get their medicines in the community

The ways in which people access medicines relate to the three main groups of medicines defined by the Medicines Act 1968. This is shown in Table 12.1.

Table 12.1

Three main groups of medicines defined by the Medicines Act 1968

| Prescription only medicines (POM) | Medicines that can only be obtained with a prescription |

| Pharmacy (P) | Medicines that can be bought in a pharmacy but their sale must be supervised by a pharmacist |

| General sale list (GSL) | Medicines that can be bought over-the-counter without pharmacist supervision in a wide range of retail outlets such as supermarkets, garages and health food stores |

Prescribing and prescribers

• Two types of prescriber: medical prescriber and non-medical prescriber

• Two types of prescribing: independent prescribing and supplementary prescribing

• Three types of independent prescriber apart from doctors and dentists: Nurse/midwife independent prescriber, pharmacist independent prescriber and community practitioner nurse prescriber.

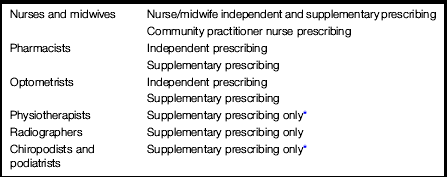

Medical prescribers are doctors (and dentists) who are licensed to prescribe when they complete their training. Non-medical prescribers must successfully complete a specific course of preparation which meets the standards of their professional regulatory organisation, for the type of prescribing they are eligible to undertake. Table 12.2 lists the practitioners who are currently eligible to become non-medical prescribers. However, further changes in legislation will extend prescribing roles further, particularly in relation to allied health professionals.

Table 12.2

Practitioners who are eligible to undertake training to be non-medical prescribers

*Independent prescribing by appropriately qualified practitioners will be introduced in 2014.

Legal restrictions apply to each professional group regarding the items they can prescribe, either as an independent or supplementary prescriber. For example, community practitioner nurse prescribers are only permitted to prescribe from the Nurse Prescribers Formulary for Community Practitioners. This contains dressings and appliances and a limited number of medicines, including some POMs, which have been selected to support community nursing interventions. Nurse independent prescribers can select items from the British National Formulary (BNF). Table 12.3 summarises the scope of prescribing for each type of prescriber.

Table 12.3

| Practitioner | What they can prescribe |

| Doctors | Any medicine listed in the British National Formulary (apart from Schedule 1 controlled drugs) |

| Dentists | From a formulary listed in the British National Formulary |

| Nurse independent prescribers | Any medicine listed in the British National Formulary for any medical condition within the prescriber’s competence including Schedule 2–5 controlled drugs |

| Pharmacist independent prescribers | Any medicine listed in the British National Formulary for any medical condition within the prescriber’s competence including Schedule 2–5 controlled drugs |

| Optometrist independent prescribers | Any licensed medicine for conditions that affect the eye and surrounding tissue, except controlled drugs |

| Community practitioner nurse prescriber | Only items listed within the Nurse Prescribers Formulary – for Community Practitioners (current edition 2011–2013). This is published as a separate booklet but also listed as an appendix in the BNF |

| All supplementary prescribers: nurses, midwives, pharmacists, optometrists, radiographers, physiotherapists, chiropodists/podiatrists | Any medicine identified in the clinical management plan, including controlled drugs, for any condition within the prescriber’s competence |

From nurse prescribing to non-medical prescribing

In 1994, teams of qualified health visitors and district nurses in England successfully piloted nurse prescribing using a nurse prescriber’s formulary, which is similar to the Nurse Prescribers Formulary for Community Practitioners used today. A nationwide programme to implement nurse prescribing commenced in 1997, and all practicing health visitors and district nurses attended their local universities to complete a 2–3-day training programme. In 1999, nurse prescribing training became part of all health visiting and district nursing programmes. This means that district nursing and health visiting were the first, and remain the only, professional groups for which non-medical prescribing is integral to their role.

In 2001, extended nurse prescribing was introduced and included other categories of nurses and midwives. A new course was developed in accordance with NMC standards, which was more lengthy and in-depth and prepared practitioners for independent and supplementary prescribing. Although the range of prescribable items was much broader than in the formulary for community nurses, prescribing was restricted to specific items for specific conditions and consequently, not applicable to all areas of clinical practice. Not until 2006 did new legislation allow Nurse Independent Prescribers to prescribe from the entire BNF and include allied health professional groups in non-medical prescribing. Although there were limitations regarding controlled drugs at this time, in April 2012, legislation was enacted to allow Nurse Independent Prescribers to prescribe schedule 2–5 controlled drugs for any medical condition within their competence. Nurses continue to be the largest professional group who are qualified to prescribe. In England, 2–3% of the registered nurse and pharmacist workforce are independent prescribers (Latter et al 2011).

Government policy in all four UK countries continues to promote non-medical prescribing as an important method of improving the quality of patient care, giving people easier access to treatments and services they require and making best use of the knowledge and skills of the professionals involved. An evaluation of nurse and pharmacist independent prescribing in England, commissioned by the Department of Health, reported prescribing to be safe and clinically effective, increased the quality of services and was very acceptable to patients (Latter et al 2011).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree