SUBJECT KNOWLEDGE

• The action of medicine upon the body

• Potential non-therapeutic action by medicines

• Calculation of medicine dosages

• Routes of medicine administration

CARE DELIVERY KNOWLEDGE

• Practice knowledge for safe medicines management using application of research evidence

• Assessing clients in relation to medicines management

• Planning to administer a medicine

• How medication administration can be evaluated

PROFESSIONAL AND ETHICAL KNOWLEDGE

• How medication errors can be effectively managed

• The legal acts governing the storage and administration of medicines in the UK

• Prescribing medicines

• Moral and ethical dilemmas that can arise within medicines management

PERSONAL AND REFLECTIVE KNOWLEDGE

• Application of principles of medicines administration across all branches of nursing

• Awareness of personal position in both the giving and the using of medicines

INTRODUCTION

In most healthcare settings, medicines need to be managed for some of the client group for whom there is responsibility. This chapter explores key information for nurse decision making about medicines management, including the practice of administering medicines. Associated elements related to licensing, prescribing and dispensing medicinal treatment will be explored and the related element of medicines dosage calculation will be addressed.

The broad concept of ‘medicines management’ is one which is multiprofessional. It is defined as: ‘The clinical, cost effective and safe use of medicines to ensure patients get the maximum benefit from the medicines they need, while at the same time minimizing potential harm’ (Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency 2004, cited by Nursing and Midwifery Council 2008b).

The safe management of medicines includes many component parts. Some examples are the purchase, supply and delivery, administration and evaluation across a range of situations, which have relevance for pharmacists and for medical and non-medical prescribers, including nurses. Without a wider consideration of care by others, such as pharmacists, the concerns of nurses in giving medicines safely and effectively would be impossible. However, this chapter intends to focus on nursing. The chapter will therefore address knowledge related to the preparation and follow-up required in giving a medicine within medicines management for nursing specifically, including knowledge for understanding the way medicines are able to enter the body and the effects that may occur both therapeutically and non-therapeutically as a result of treatment. Although it is not possible to offer comprehensive advice related to individual medications in this respect, some common groups of medicines will be considered. For more detail, annotated further reading is provided.

Effective management of medicines by nurses may involve educating other carers to give medicines or educating clients to self-administer medicines. There is also a role in health promotion with regard to the safe handling and storage of medicines in both hospital and community settings.

OVERVIEW

Subject knowledge

The physical aspects related to treatment with medicines are introduced, with a particular emphasis upon the mechanical and biological bases. Here, classification of medication by type is examined, followed by a consideration of the possible routes of administration, calculation of correct doses and examination of how the body deals with substances introduced to it. Further reading is offered and viewed as an essential development.

Wider psychosocial aspects of medicine use are included, with a consideration of the potential for abuse of medication and the societal impact of substance use today.

Care delivery knowledge

The role of the nurse in medicines management is explored. This discussion relates specifically to decision making in the assessment, planning, implementing and evaluation and recording of total care. It is intended that this section should lead to a deeper understanding of a nursing practice role.

Professional and ethical knowledge

This part addresses issues related to legality and accountability, as well as examining ethical issues in medicines management. Incidents such as errors in medication are explored and discussed in detail. Contemporary guidance relating to the eligibility of nurses to prescribe medicines is discussed, and resources are offered for further knowledge development in this area.

Personal and reflective knowledge

Throughout the chapter you are encouraged to think reflectively over issues related to the care that you give. It is anticipated that concepts raised throughout the chapter will be applied as a knowledge base for nursing practice. Throughout the chapter you will be invited to extend your thinking and knowledge further through consideration of evidence boxes, decision-making exercises and reflective points. ‘Evolve’ materials will be used to provide further information related to elements in the chapter.

On pages 246–247 there are four case studies with reflective questions, each relating to one of the branches of nursing. These can operate as a starting point for application of the principles identified within the chapter. You may find it helpful to read one of them before you start the chapter and use it as a focus for your reflections while reading. Of course, you should also explore examples from your own experience.

SUBJECT KNOWLEDGE

BIOLOGICAL

THE PHYSICAL BASIS OF MEDICINE ADMINISTRATION

Defining a medicine

When examining nursing issues related to the medicinal treatment of clients, there has been much debate about what constitutes a medicine, as well as what constitutes an appropriate role for nurses in treating their clients. Indeed, such has been the confusion over terminology and definition in this area of practice that both National and European regulatory bodies (Department of Health, 1999 and European Parliament and Council, 2001, Article 1) have produced guidance to help facilitate a clear definition of what a medicine might be. The definition below is presented from the EC Directive above. It is useful to know about this definition because it is used by the Medications and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) in the UK when they consider whether a substance is to be classified as a medicine or not.

A medicine is:

(a) Any substance or combination of substances presented as having properties for treating or preventing disease in human beings;

or

(b) Any substance or combination of substances which may be used in or administered to human beings either with a view to restoring, correcting or modifying physiological functions by exerting a pharmacological, immunological or metabolic action, or to making a medical diagnosis.

(European Parliament and Council 2001/83/EC Article 1)

Marketing authorization

Medicinal products are currently regulated in the UK by the MHRA. They ensure that product licensing and monitoring concord with European Directives and UK law. Similar arrangements are in place elsewhere in Europe and the system is comparable with the rest of the world. Products are now issued with a marketing authorization which licenses them as safe for use. The marketing authorization includes a ‘Summary of Product Characteristics’ which stipulates safe routes of administration, dose strengths, constitution and the client group who can be considered (Medicines and Health Care Regulatory Agency 2008). Details of any summary of product characteristics can be found within the guidance details included in the medicine packaging, and these should be adhered to in order to ensure clients’ safety. If a medicine is prescribed that has no national marketing authorization, or is exempted from this, then this is considered to be prescribed ‘off licence’. If a medicine is prescribed ‘outside of the summary of product characteristics’ guidance included within the marketing authorization, then this is considered to be ‘off label’. The use of off licence and off label medication is generally not advised and under current EU Directives will reduce significantly after a transitional period in place for some medicines until 2011. However, it is not illegal and is accepted by the medicine and pharmacy professions (Turner et al 2002) and the nursing regulatory body for nursing to be acceptable in some circumstances (Nursing and Midwifery Council 2008b). It is most likely to be found in the areas of neonatal nursing and paediatrics. There are implications in accepting this kind of prescribing, and these are addressed within professional issues later in this chapter.

In addition to the marketing authorization, all medications are issued with both a brand name and a British Approved Name or BAN. The brand name is the one by which the product is marketed, while the BAN is the generic name used in prescribing. Health carers should at all times use the BAN, while being mindful of different brands. Manufacturers must legally meet stringent requirements for labelling and provision of instructions relating to medicines. Though outside the scope of this chapter, this element is addressed thoroughly by Downie et al (2007) and their text is useful should you wish to extend your reading.

Classification of medicines

Medicines can be classified two ways. Firstly, there is the legal classification of medicines, which categorizes medicines according to requirements governing their supply to the general public. Contemporary legal classification continues to be derived from the Medicines Act 1968 and the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 and will be addressed in more detail in the Professional Knowledge part of this chapter. Secondly, and less formally, medicines are classified into groups that indicate the effect on a body system, the symptoms relieved, or the desired effect of the medication (e.g. Waller et al., 2005 and Downie et al., 2007). In fact it probably does not matter, and is as much personal preference as anything else.

A list of all medicines and their side-effects would be inappropriate in a chapter such as this so reference to formularies such as the British National Formulary (Joint Formulary Committee 2008) and the British National Formulary for Children (Paediatric Formularies Committee 2007) is recommended. However, it is acknowledged that a clear framework for categorizing drugs for further reference can be useful. The framework in Box 10.1 has been devised to assist nurses and students working and studying in practice. Although it must be emphasized that no nurse should give medications they are not familiar with, it is sometimes helpful to jot down notes about medications. By carrying this framework into the practice area, medicines may be noted down as you discover them in use, allowing access for revision and more in-depth study at a later date.

Box 10.1

| Type of treatment or area | Name of medicine and brief notes for future reference |

|---|---|

Cardiovascular Respiratory Gastrointestinal tract Renal Central nervous system Analgesic Hypnotic Psychotropic Anaesthetic Blood Infection Antibiotic (or bactericidal/bacteriostatic/antiseptic) Antifungal Antiviral Immunization Vitamin, fluid or electrolyte imbalance Hormone or endocrine imbalance Cytotoxic treatment |

• In your practice identify one medicine used within each of the classifications in the framework in Box 10.1 and find out all you can about it using the references for further reading identified at the end of the chapter. If possible, reflect on the exercise with colleagues.

• Use your findings to discuss what factors may influence a nursing decision not to give an identified medicine to a client.

Although a useful way of identifying individual uses for medications, the above framework categories are not mutually exclusive. Looking at your list, can you identify any medication that may fit into more than one of the above categories? What does this tell you about using this drug therapeutically?

CALCULATING MEDICINE DOSES

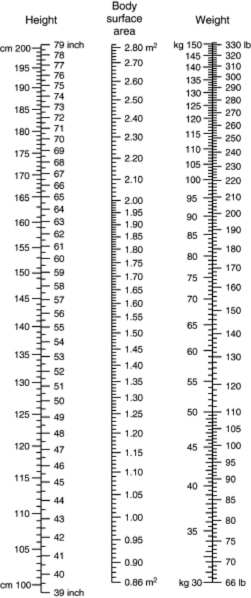

Calculation of a therapeutic yet safe dose of any medication is achieved by weighing the client and determining a safe dose per kilogram or by calculating the client’s body surface area. In critical care areas a nomogram (see example in Fig. 10.1) may be used to determine estimated surface area.

|

| Figure 10.1 (reproduced with kind permission from Geigy Scientific Tables 1990, 8th edn, vol. 5, p. 105, © Novartis). |

Medicines prescribed regularly in an adult setting may be appropriate for a wide range of clients and are often prescribed in a form that is held as stock by the pharmacist. For instance, an antibiotic such as ampicillin may be prescribed as a 250 milligram (mg) dose. The pharmacist sends capsules which have a strength of 250 mg per capsule so that the client requires one capsule. However, where children or the elderly are concerned, or where medication is particularly toxic, the dose can be calculated according to the weight of the client in milligrams per kilogram as recommended by the pharmaceutical company. This may not conveniently fall into a single unit dose such as one capsule. Once a dose has been ascertained, it is up to the nurse to decide that the prescription is correct and ensure that it is given. This means a further calculation may be necessary. A formula for calculating medicines is shown in Box 10.2.

Box 10.2

So if the dose prescribed is 500 mg of amoxicillin and the stock dose is 250 mg per one tablet (volume), the calculation is:

, so two tablets are given

, so two tablets are given

Medicine doses are calculated using the Système International (SI) or metric system and are described in units of this system. When performing any calculation it is important that you ensure that the same SI unit is used for the stock and the prescribed dose. If the prescribed dose is in milligrams (mg) and the available medication is only available in grams (g), then one of these needs to be converted before a calculation can take place. It would be usual to convert grams to milligrams (see Annotated Further Reading for more information).

It is fair to say that many nurses find applied numeracy like this quite difficult, and it is critical that you ensure that you are competent in this area for your clients’ safety. If you are a student nurse in the UK you will be expected to complete assessments relating to the use of numeracy in practice to help to demonstrate that you are a safe practitioner when you qualify. However, help is at hand. It is most important for a safe practitioner to be aware of their strengths and weaknesses and seek out help when necessary. Sources of help might include lecturers in university or mentors in placement, an online facility, such as that offered by learndirectuk or the Mathcentre (see section on websites at the end of the chapter) or one of the many text books written specifically for nurses (e.g. Lapham and Agar, 2003, Gatford and Philips, 2006 and Chapelhow and Crouch, 2007). Universities and colleges also have study support facilities that can be accessed by students.

Mrs Johnson, an elderly lady, is found to be unwell while taking prescribed digoxin. The dose is reduced from 125 micrograms to 62.5 micrograms twice daily. The solution of digoxin provided for Mrs Johnson contains 50 micrograms per mL. Try to decide how much medicine Mrs Johnson should receive at one time.

MEDICINES ADMINISTRATION

Routes of administration

Nurses have a useful contribution to make in their knowledge of what preparations of medication are available and appropriate for their clients, and due to their assessment they are uniquely aware of their clients’ needs. When selecting a route for administration nurses and doctors must work with the client to provide an optimum treatment programme that is safe and acceptable (Table 10.1).

There are many different routes that can be selected for administration, as shown in Table 10.1. Think about a recent practice experience where a medication was given.

• What route was used?

• Was this the only possible way to give this medicine or could other routes have been selected?

• What are the issues if more than one route were possible?

• What did you learn from this exercise – record your findings in your portfolio.

| Route | Notes |

|---|---|

| Oral | Including anything swallowed to the stomach or via nasogastric tubes |

| Sublingual/buccal | Allowed to dissolve under the tongue or in the cheek |

| Topical/local application | Including application into eyes, ears, or insertion into vagina, rectum |

| Transdermal | Through slow release patches adhered to the skin |

| Inhalation | Including via masks, nebulizers, breathing tubes |

| Intravenously/intra-arterially | Administered into a vein or artery by a doctor or nurse with appropriate advanced qualifications |

| Subcutaneously/subdermal | By injection under the cutaneous or dermal skin layers |

| Intramuscularly | By injection into muscle layers |

| Intrathecally | Administered by a doctor into the thecal cavity via a lumbar puncture procedure |

| Intraosseously | Administered by doctor into bone cavity (used for urgent access) |

| Other | It is possible for doctors to use other routes (e.g. into body cavities such as the pleural space or peritoneal cavity) in specific circumstances |

Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Medication given is absorbed from the point of administration and into the cardiovascular system. Unless the medication is given by another route (thus bypassing this phase), nurses must be aware of the effects of the medicine in the effectiveness of absorption, and also the potential effect of the medicine at the site where it is being absorbed. With oral medication, consideration must include the effects of gastric secretion upon the efficacy of the drug and the potential effects of the medication upon the client’s gastrointestinal tract.

With the administration of topical medications, there is usually an expectation that the desired effect will predominate at the local site. However, the potential for long-acting absorption of medication systemically is recognized in some situations. Transdermal patches are one example; these slowly release medications, for example progesterone and oestrogens for hormone replacement therapy, or nicotine to aid in the cessation of smoking. Nurses caring for patients using topically applied products must consider what effect (if any) the absorption of such medication may have upon a client’s systemic well-being, especially if the intended action is purely a local one.

Distribution

Once in the cardiovascular circulation, the medication is carried to its site of action. Again, there are areas of nursing knowledge that are important for consideration. It is useful to understand how the treatment is carried in the blood, since many medicines are bound tightly to plasma proteins while others are not. If a medicine has a high affinity for plasma proteins it may be necessary to give a large dose of the medication to achieve a therapeutic effect since only the proportion of the medicine that is not bound to the plasma proteins can be used effectively. Commonly used medicines with a high affinity for plasma proteins (more than 80% bound) include the antidepressant amitriptyline, and the anxiolytic diazepam. Other medicines with a high affinity for plasma proteins are propanolol, warfarin, furosemide and the antibiotics erythromycin and rifampicin. A comprehensive review of protein bound medications is offered by Kee & Hayes (2005).

When planning to administer medicines, a factor that may affect the client’s concentration of plasma proteins should be considered. This is because an individual with a reduced albumin concentration may be at risk of toxicity if a dose of medication with a high affinity for plasma protein is given. Other issues that should be considered in relation to the distribution of medication via the cardiovascular system include the rate and volume of perfusion to the desired area as any reduction in access to the required site may reduce the impact of the treatment offered. Additionally some areas of the body are protected from receiving many medications as a result of physiological barriers. The brain is one such area as the meninges around the central nervous system create a blood–brain barrier. Another area that selectively reduces the passage of substances is evident during pregnancy when the placenta offers a barrier between mother and baby. However, it should be noted that some substances may pass through these barriers. In nursing, the implications of the effectiveness of such barriers must be addressed when making informed decisions about nursing care. It is critical to assess the possibility of pregnancy in all premenopausal women who require medicinal treatment, with particular awareness of the potentially hazardous effects in causing fetal abnormalities of drugs such as phenytoin and tetracyclines, which can pass the placental barrier. Finally, the distribution of medication to infants via maternal breast milk must also be acknowledged. In some cases medication given to the mother may be safe for her, but can have toxic effects on the baby. For more information about the effects of specific medications in breastfeeding please refer to the Annotated Further Reading at the end of the chapter.

Mr Jack Harvey, aged 85 years, is in hospital following a recent diagnosis of congestive cardiac failure. He has been prescribed propanolol, but after a few days his heart rate drops to less than 60 beats/min (compared to a more usual 80 beats/min) and he complains of feeling unwell.

• What could be wrong with Mr Harvey?

• Within coronary care, there is a variety of medicines that act upon the heart in different ways. Propanolol is a beta blocker. Find out how beta blockers work and compare their action with that of the digitalis group of medicines.

• What special considerations might you need to remember when administering medicines to clients who are elderly?

Metabolism

Metabolism (or breakdown) of any medication usually occurs in the liver (hepatic system). This may be therapeutic, in aiding the removal of active medication from the body by rendering it to inactive waste metabolites, or may hinder the effects of treatment, depending upon when such metabolism takes place. This issue is particularly pertinent when considering medicines that are administered orally, since much absorption via the gastrointestinal tract results in direct passage to the liver through the hepatic portal vein. In this situation the liver metabolizes a proportion of the medication (which varies between medications) before the medication reaches the cardiovascular circulation and is transported to the site of therapeutic benefit. This is known as ‘first pass’ metabolism, and although sometimes such a metabolism may be beneficial, as the metabolites themselves may have a therapeutic function, often it reduces the available therapeutic dose of medication by inactivating it. First pass metabolism is reduced in individuals with impaired hepatic function, and this is vital knowledge for nursing consideration in order to maintain the safety and well-being of the patient.

Finally, it is important to understand that it is possible to overload the liver with toxins resulting from the breakdown of medication as well as other substances such as alcohol, and this leads initially to an inability of the liver to cope effectively. If the liver continues to be overloaded with toxins over a prolonged period or is subjected to recurrent episodes of overload, damage may occur. This can create a permanently reduced hepatic function.

When considering administration to infants and young children, it is essential to recognize that in the young the ability to detoxify medicines is not mature, and therefore extreme caution should be taken when checking for an appropriate dose.

Excretion

After a variable period of time in the body the medication given to the client will be excreted. This is mostly via the kidneys, although other routes of excretion include the lungs, via bile into faeces, and in lactating mothers, breast milk. There may also be some excretion through sweat glands onto the skin surface (Downie et al 2007). Perhaps the most important factor in medicine excretion, however, is the speed at which it is lost from the body. The balance between absorption and excretion determines the half-life of a medicine. This is the time it takes for the concentration of the medicine in the plasma to fall by 50% (Downie et al 2007). Clearly, a medicine with a long half-life can accumulate easily within the plasma. Those medicines that are particularly problematic are monitored carefully through checking blood plasma levels to ensure that plasma levels do not become dangerously high.

An important consideration for nurses, therefore, relates to factors about the client that may affect the response and half-life of a medicine. For example, clients who are at the extremes of the age continuum or have renal impairment require particular consideration. The infant does not develop full renal and urinary tract function until after the first year of life, while the renal function of the elderly (over 80 years of age) deteriorates to about half the capacity of a young adult. Renal impairment can affect the excretion of medicines from the body, resulting in a build-up of metabolites, or in some instances medicines, in the circulation. A knowledge of such possibilities may alert you to making a decision to include specific points for observation related to medication in the client’s plan of care. A full introduction to factors that may affect the response of medication can be found in Kee and Hayes, 2005 and Downie et al., 2007: Ch. 6).

Simon is severely learning disabled and has difficulty in maintaining urinary continence due to poor bladder tone causing retention of urine and dribbling incontinence. He is cared for by his mother who maintains that clean intermittent catheterization techniques aid Simon’s urinary continence, but he occasionally develops urinary tract infections. Simon’s mother, while managing his infection, comments to the practice nurse that Simon’s urine smells of the current antibiotic treatment and wonders why.

• How could you reassure Simon’s mother that all is well?

• Find out how antibiotics work and what broad classifications can be identified.

• In a society that does not tolerate ill health, people are inclined to ask for antibiotics for minor infections. Reflect for a few minutes about the impact this may have in the long term.

Pharmacodynamics

Once a medicine has reached the site of therapeutic benefit it is able to exert a physiological effect before being excreted by the body. This is identified as pharmacodynamic action, and examination of this action of medicines in the body is comprehensively addressed within specific pharmacology texts such as Kee & Hayes (2005). A more detailed consideration is presented by Waller et al (2005). It is important to realize, however, that even with today’s rapidly advancing understanding of medical science, the frontiers of clinical pharmacology are still being extended.

POTENTIAL ADVERSE EFFECTS OF ADMINISTERING MEDICINES TO CLIENTS

Although the aim of using medicinal treatments for clients may be therapeutic, diagnostic or preventive, it is simplistic to believe that all medicines given are completely therapeutic in all cases. For nursing, the aim has always been recognized as ‘To do the client no harm’ (Nightingale 1859). This next section will explore potential threats to such ideals.

Gaining a therapeutic dose

In order for medicine to be effective, the dose for your client must be sufficient to be effective, but not too much, in which case the client may risk toxicity or poisoning. Factors in achieving a therapeutic dose are related to nursing and medical skill in prescribing and calculating the correct dose of medication and also the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic capacity of the client. This may be related to their age, lifestyle or health condition, as highlighted above. However, even with a therapeutically assessed dose of medication, the response of individual clients can vary significantly, and thus a potentially useful medicine may be harmful. Nurse decision making contributes to risk reduction associated with the administration of medicines, and the identification of potential adverse effects is essential. Some potential adverse effects arising when giving a therapeutic medication are identified in Table 10.2.

| Adverse effect/side effect | Nature of reaction |

|---|---|

| Idiosyncrasy | Often genetically determined |

| Hypersensitivity/allergy | May be life-threatening (anaphylaxis) |

| Skin reactions | Pruritus (itching) Urticaria (nettle rash) Erythematous eruptions (flushing and skin rashes) Skin peeling Eczematous lesions |

| Blood dyscrasias | Aplastic anaemia (due to bone marrow suppression) Thrombocytopenia (loss of platelets) Agranulocytosis (loss of white blood cells) |

| Gastrointestinal upset | Diarrhoea Dyspepsia Ulceration Nausea Vomiting Sore or dry mouth Anal pruritus Flatulence Abdominal pain |

| Central nervous system upset | Drowsiness Headache Dizziness Nausea Vomiting Tinnitus |

| Photosensitivity | Acute ocular sensitivity to light |

| Tolerance | The client responds increasingly less effectively to a regular dose of medication |

| Dependence | The client may become addicted to the medication |

As well as the adverse effects of giving any single medication to an individual, external influences may also cause damage. Clients may already be taking other medications that could interact with new treatment, causing adverse effects or altering the pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamic action of either medication. A common outcome is a reduced or halted action (antagonism), which may be useful for use as an antidote, preventing the action of a medication once it has been given, or a potentiated action (synergism). Other reactions are also possible and for a comprehensive listing of currently known interactions see the British National Formulary (British Medical Association 2007).

Polypharmacy

An interaction between different drugs, as described above, may not be restricted to two substances, but may involve a multiplicity of medical treatments. This type of interaction is known as ‘polypharmacy’, and is documented as a problem in the international healthcare literature, across many populations including the elderly, those with mental health problems and children and adolescents.

The role of the pharmacist

The responsibility of the pharmacist both in hospital and in the community is to ensure that any medications dispensed can be taken safely by the individual for whom they are prescribed. Within the hospital setting the pharmacist checks the client’s prescription and can observe any possible effects of combining prescribed medications inappropriately. However, this is much more difficult within the community setting. Indeed, such is the concern in the UK that in 2005, the Department of Health initiated pharmacy based ‘medicines use review’ service for patients with chronic illness or those taking more than one prescribed medicine. This service is free to clients and is provided by primary care trusts through contracts with participating community pharmacies under the NHS (Pharmaceutical Services) (Amendment No 2) Regulations 2005 (SI 1501), which came into force on 5 July 2005 (National Health Services 2005). From a nursing point of view, however, it is essential that careful assessment of clients’ medication and treatment is noted upon any assessment made, with care taken to monitor situations where polypharmacy occurs. Unfortunately, however, this service is limited by the number of reviews that may be contracted annually because of cost. This means that not everyone who may require a review will necessarily receive the opportunity. The service has also not been in existence for long enough for evaluation of its effectiveness to take place. Current evidence would suggest that a greater intervention may be required in order to achieve success in reducing the effects of polypharmacy.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access