Medicine and Ethics

Learning Objectives

1. Define, spell, and pronounce the terms listed in the vocabulary.

2. Differentiate between legal, ethical, and moral issues affecting healthcare.

3. Compare personal, professional, and organizational ethics.

4. Identify the effect personal ethics may have on professional performance.

5. Recognize the role of patient advocacy in the practice of medical assisting.

6. Explain rights and duties as related to ethics.

7. List and define the four types of ethical problems.

8. Discuss the process used to make an ethical decision.

11. Explore the role of confidentiality as it applies to the medical assistant.

14. Note some of the concerns about ethics that apply to genetic information.

Vocabulary

advocate (ad′-vuh-kat) One who pleads the cause of another; one who defends or maintains a cause or proposal.

allocating (a′-luh-ka-ting) Apportioning for a specific purpose or to particular persons or things.

annotations (a-nuh-ta′-shuns) Notes added by way of comment or explanation.

beneficence (buh-ne′-fuh-sens) The act of doing or producing good, especially performing acts of charity or kindness.

clinical trials Research studies that test how well new medical treatments or other interventions work in the subjects, usually human beings.

disparities (di-spar′-uh-tes) Marked differences or distinctions.

fidelity (fuh-de′-luh-te) Faithfulness to something to which one is bound by pledge or duty.

genome (jeh′-nom) The genetic material of an organism.

idealism The practice of forming ideas or living under the influence of ideas.

infertile Not fertile or productive; not capable of reproducing.

introspection (in-truh-spek′-shun) An inward, reflective examination of one’s own thoughts and feelings.

nonmaleficence (non-mal-fe′-zens) Refraining from the act of harming or committing evil.

philosopher A person who seeks wisdom or enlightenment; an expounder of a theory in a certain area of experience.

postmortem Done, collected, or occurring after death.

procurement (pro-kuhr′-ment) To get possession of, to obtain by particular care and effort.

ramifications (ra-muh-fuh-ka′-shuns) Consequences produced by a cause or following from a set of conditions.

reparations (re-puh-ra′-shuns) Amends, acts of atonement, or satisfaction given as a result of a wrong or injury.

sociologic Oriented or directed toward social needs and problems.

surrogate (suhr′-uh-gat) A substitute; to put in place of another.

unique identifiers Codes used instead of names to protect the confidentiality of the patient in a method of anonymous HIV testing.

veracity (vuh-ra′-suh-te) A devotion to or conformity with the truth.

Scenario

Monica Johnson has been employed for 6 months as a medical assistant in a family practice. She works as the clinical medical assistant for Dr. Richard Wray. One of Dr. Wray’s patients, Anna Walsh, recently adopted a baby after 8 years of trying to conceive a child. The baby, Delaney Gracelia, was born to a single mother, Susan, who participated in an open adoption in which she and the Walshes met and got to know each other during her pregnancy. Susan dated the baby’s father for about 6 months before discovering that she was pregnant, and they are no longer dating. Susan wanted to make a good decision for the baby and decided to place her for adoption. Dr. Wray performed some genetic testing on Delaney, and the adoptive parents were involved throughout the pregnancy, even meeting Delaney’s birth mother for physician appointments from time to time. Monica observed both Susan and the Walshes and saw many benefits from the arrangement, noticing that everyone was primarily concerned with Delaney and her happiness and well-being. However, some periods were difficult for both sides. This prompted Monica to give some thought to her own feelings and ideas about many different ethical situations and issues and how she would react in the face of having to make ethical decisions.

While studying this chapter, think about the following questions:

• What difficulties do patients placing their babies for adoption face?

• What difficulties do adoptive parents face when participating in an open adoption?

• How can the medical assistant be supportive of both the adoptive parents and the birth mother?

• Should the medical assistant discuss personal beliefs about ethical situations with patients?

Ethics can be defined as the thoughts, judgments, and actions on issues that have implications of moral right and wrong. Various beliefs exist about what is and is not ethical in everyday life and in the medical profession. The decisions that people make based on ethical beliefs can quite possibly alter the course of human existence. Ethics are different from legal issues mainly because something that is legal is not necessarily ethical. Ethics is considered a higher authority than legality. The American Medical Association’s Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs (CEJA) clarifies the relationship between law and ethics as follows: Ethical values and legal principles are usually closely related, but ethical obligations typically exceed legal duties. In some cases, the law mandates unethical conduct. In general, when physicians believe a law is unjust, they should work to change the law. In exceptional circumstances of unjust laws, ethical responsibilities should supersede legal obligations. Ethics and morals are more closely related, although ethics often are attributed to professional interactions, whereas morals are usually personal in nature. Medical assistants not only must have a strong knowledge base about ethical issues they might face throughout their careers, they also must come to terms with some of the deeply rooted value systems that have been a part of their lives since youth. The trials and tribulations we have experienced, as well as the joys, all influence our thought patterns when we are faced with an opportunity to make a good ethical decision.

Personal, professional, and organizational ethics all contribute to the way the medical assistant approaches the patient. For instance, if a medical assistant personally believes that a patient should be taken off life support when there are no signs of brain activity, he or she must understand that professionally, this decision must be left to the patient’s family members. The medical assistant must not force his or her personal ethical beliefs on the patient or family members. Organizations will offer ethical guidelines as well in the form of policies and procedures; for example, each medical assistant is required to maintain patient confidentiality. This practice reflects the organizational ethic that all patients have the right to confidentiality of their information and records (Procedure 6-1). Personal and professional ethics must be kept separate so that patients can make their own decisions regarding their healthcare (Procedure 6-2).

History of Ethics in Medicine

From earliest recorded history, humans have pondered ethics, or the judgment of right and wrong. Ethics should not be confused with etiquette. Etiquette refers to courtesy, customs, and manners, whereas ethics explores the moral right or wrong of an issue. It is not surprising that for centuries, the field of medicine has set for itself a rigid standard of ethical conduct toward patients and professional colleagues.

The earliest written code of ethical conduct for medical practice was conceived in approximately 2250 BC by the Babylonians. It was called the Code of Hammurabi. It elaborated on the conduct expected of a physician and even set the fees a physician could charge. The code was quite lengthy and detailed, which is probably the reason it did not survive the ages. In approximately 400 BC Hippocrates developed a brief statement of principles that remains an inspiration to the physicians of today. The Oath of Hippocrates has been administered to many medical graduates. The most significant contribution to medical ethics after Hippocrates was made by Thomas Percival, an English physician, philosopher, and writer. In 1803 he published his Code of Medical Ethics. Percival was very concerned about sociologic matters and took great interest in the study of ethical concepts as they related to the medical profession.

In 1846, as the American Medical Association (AMA) was being organized in New York City, medical education and medical ethics already were considered important aspects of the profession. At the first annual AMA meeting in 1847, a Code of Ethics was formulated and adopted. It specifically acknowledged Percival’s code as its foundation, and this document became a part of the fundamental standards of the AMA and its components. Even today, sections of the AMA Code of Ethics stem from Percival’s writings.

Who Decides What is Ethical?

When we weigh the question of who decides what is ethical, the answer is evident: you do. Every day medical professionals face the task of making ethical decisions. As with any important choice, the short- and long-term effects and consequences must be considered. Although depending on groups and committees to guide ethical decisions is a completely acceptable practice, the responsibility for making these decisions ultimately rests with the individual (Figure 6-1).

Organizations that study ethical dilemmas may decide that a concept such as abortion is an ethical medical practice. But if an individual does not find abortion to be an acceptable practice for religious or other reasons, abortion is not ethical for that individual. A great freedom that Americans often take for granted is that we can exercise free will in decisions related to individual conscience in this country and that we can choose from a variety of options; however, we must exercise this responsibility carefully.

The Role of the American Medical Association and Its Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs in Issues of Ethics

The AMA serves physicians as a national organization that provides various types of information and support. One of the most important facets of the AMA is its Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs. The CEJA consists of nine active members of the AMA, including one resident physician member and one medical student member. It is responsible for interpreting the AMA Principles of Medical Ethics as adopted by the House of Delegates of the AMA. The AMA’s Code of Ethics has four components:

• Principles of medical ethics

• The fundamental elements of the patient-physician relationship

• Current opinions of the CEJA with annotations

The Code of Medical Ethics: Current Opinions with Annotations contains the first three components, with discussion of more than 135 ethical issues encountered in medicine. A separate publication, Reports of the Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs, discusses the rationale of the council’s opinions. The AMA Principles of Medical Ethics has been revised several times to take into account developments in medicine, but the moral intent and overall idealism of these principles have not changed.

Making Ethical Decisions

An understanding of a few of the elements of ethics, the different types of ethical problems, and how a good ethical decision is made is important before we discuss the opinions of the CEJA. Then, as some of the opinions are presented in this text, students can begin to evaluate their own positions on each issue. This section enables the medical assistant to recognize the types of ethical problems that might arise in the physician’s office and provides a pattern to follow in making an ethical decision.

Elements of Ethics

Dr. Ruth Purtilo, an authority on ethics in medicine, has written a book on the subject, Ethical Dimensions in the Health Professions. She presents three general elements of ethics: duties, rights, and character traits. A duty is an obligation a person has or perceives himself or herself to have. A daughter may feel the obligation to care for her elderly parents, or a husband who has hurt his spouse may feel an obligation to somehow make up for his act.

Purtilo mentions several types of duties related to the medical profession. Nonmaleficence means refraining from harming oneself or another person. Beneficence means bringing about good. Fidelity is the concept of keeping promises, and veracity is the duty of telling the truth. Justice, in relation to medical ethics, deals with the fair distribution of benefits and burdens among individuals or groups in society having legitimate claims on those benefits. When a person has wronged another, he or she has a duty to make reparations, or right the wrong. Last, a person should feel grateful if he or she is a beneficiary of someone else’s goodness. This also is a type of duty.

Rights are defined as claims a person or group makes on society, a group, or an individual. The Bill of Rights appended to the U.S. Constitution guarantees certain liberties that we enjoy as American citizens. However, some individuals think that they have rights, but those rights are actually privileges. For instance, Americans do not have the “right” to healthcare services. Individuals may expect to be cared for when sick, but this is not a right guaranteed to anyone in America. Some countries provide medical care to all their citizens, but the United States is not one of those countries. A right applies to all people within a group, without prejudice.

Purtilo defines character traits as a disposition to act a certain way. A person who believes that honesty is an important character trait usually can be trusted to speak the truth. One who feels comfortable with taking small items from work for use at home may not be able to resist an opportunity to take something more valuable. Character traits certainly do not always indicate how a person will react in all situations. No human being is perfect, and we sometimes are unpredictable. Stress also can interfere with our normal reactions, and other factors, such as depression or anger, influence how we act. The phrase that someone is acting “out of character” usually means that the person is deviating from his or her normal behavior patterns.

With an understanding of these basic elements of ethics, we have a good foundation to help us look more objectively at ethical problems and solve them to the best of our ability.

Types of Ethical Problems

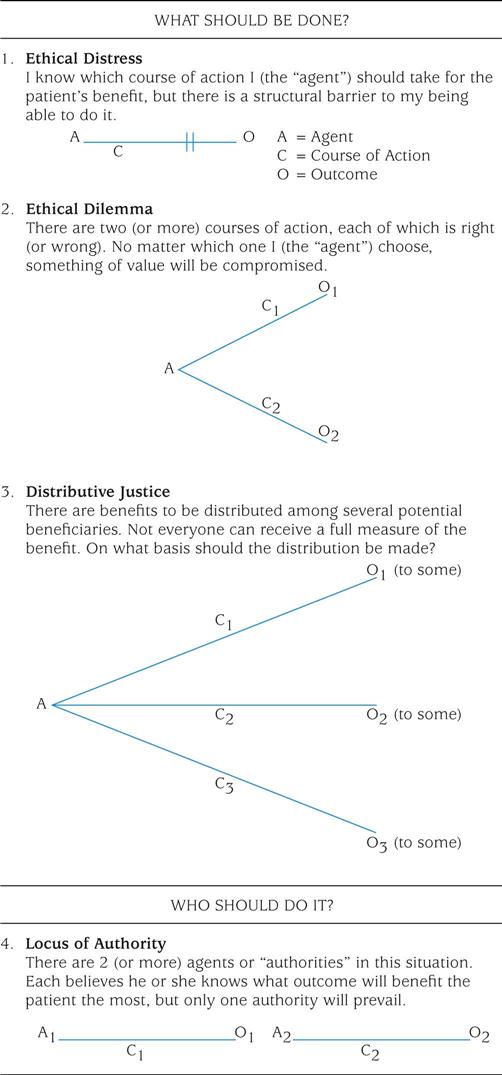

Purtilo presents four basic types of ethical problems (Figure 6-2):

Ethical distress is a problem in which a certain course of action is indicated, but some type of hindrance or barrier prevents that action. A professional knows the right thing to do but for some reason cannot do it.

An ethical dilemma is a situation in which an individual is faced with two or more acceptable or correct choices, but doing one precludes another. A choice must be made, and something of value may be lost if a second choice is eliminated. This could be viewed as the proverbial “being caught between a rock and a hard place,” when the effect of a choice made may be greater than is immediately obvious.

The third type of ethical problem is the dilemma of justice. This problem focuses on the fair distribution of benefits to those who are entitled to them. Choices must be made regarding who receives these benefits and in what proportion. Examples include organ donation and distribution of scarce or costly medications.

In locus of authority issues, two or more authority figures have their own ideas about how a situation should be handled, but only one of those authorities can prevail. If one physician feels that a patient should have surgery and another does not, how does the patient decide?

Recognizing the type of ethical problem is not always easy. Sometimes an issue is a mixture of one or more types of ethical problems. When possible, it is wise to take time to weigh the courses of action before making an important decision. Unfortunately, with the fast pace of the medical profession, this is not always possible. Some decisions must be made in a split second; therefore, having a thorough grasp of ethical decision making before the need arises is important.

The Ethical Decision-Making Process

Purtilo proposes a five-step process for ethical decision making:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree