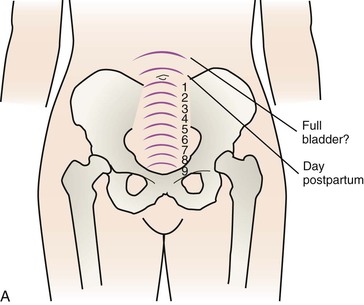

• Describe the anatomic and physiologic changes that occur during the postpartum period. • Identify characteristics of uterine involution and lochial flow, and describe ways to measure them. • List expected values for vital signs, deviations from normal findings, and probable causes of the deviations. Within 12 hours the fundus rises to the level of the umbilicus, or slightly above or below (Fig. 13-1). Thereafter the fundus descends approximately 1 cm every day. By 1 week after birth the fundus is located 4 to 5 fingerbreadths below the umbilicus. The uterus should not be palpable abdominally after 2 weeks and should have returned to its nonpregnant location by 6 weeks after birth (Blackburn, 2007). The uterus, which at full term weighs approximately 11 times its prepregnancy weight, involutes to approximately 500 g by 1 week after birth and to 350 g by 2 weeks after birth. At 6 weeks, it weighs 60 to 80 g (see Fig. 13-1). Subinvolution is the failure of the uterus to return to a nonpregnant state. The most common causes of subinvolution are retained placental fragments and infection (see Chapter 23). Immediately after the placenta and membranes are expelled, vascular constriction and thromboses reduce the placental site to an irregular nodular and elevated area. Upward growth of the endometrium causes sloughing of necrotic tissue and prevents the scar formation that is characteristic of normal wound healing. This unique healing process enables the endometrium to resume its usual cycle of changes and to permit implantation and placentation in future pregnancies. Endometrial regeneration is completed by postpartum day 16, except at the placental site. Regeneration at the placental site occurs gradually and is not usually complete until 6 weeks after birth (Blackburn, 2007). Lochia rubra consists mainly of blood and decidual and trophoblastic debris. The flow pales, becoming pink or brown (lochia serosa) after 3 to 4 days. Lochia serosa consists of old blood, serum, leukocytes, and tissue debris. The median duration for lochia serosa discharge is 22 to 27 days (Katz, 2007). In most women, approximately 10 days after childbirth the drainage becomes yellow to white (lochia alba). Lochia alba consists primarily of leukocytes and decidual cells but also contains epithelial cells, mucus, serum, and bacteria. Lochia alba may last until 6 weeks after birth (Blackburn, 2007). Persistence of lochia rubra early in the postpartum period suggests continued bleeding as a result of retained fragments of the placenta or membranes. Recurrence of bleeding approximately 7 to 14 days after birth is from the healing placental site. Approximately 10% to 15% of women will still be experiencing normal lochia serosa discharge at the 6-week postpartum examination (Katz, 2007). In the majority of women, however, a continued flow of lochia serosa or lochia alba by 3 to 4 weeks after birth may indicate endometritis, particularly if fever, pain, or abdominal tenderness is associated with the discharge. Lochia should smell similar to normal menstrual flow; an offensive odor usually indicates infection. Not all postpartal vaginal bleeding is lochia; vaginal bleeding after birth may be a result of unrepaired vaginal or cervical lacerations. Table 13-1 distinguishes between lochial and nonlochial bleeding. TABLE 13-1 Lochial and Nonlochial Bleeding

Maternal Physiologic Changes

Reproductive System and Associated Structures

Uterus

Involution process

Placental site

Lochia

LOCHIAL BLEEDING

NONLOCHIAL BLEEDING

Lochia usually trickles from the vaginal opening. The steady flow increases as the uterus contracts.

If the bloody discharge spurts from the vagina, damage to a blood vessel may have occurred during birth. If so, some of the bleeding is not just normal lochial flow.

A gush of lochia may result as the uterus is massaged. If the lochia is dark in color, it has been pooled in the relaxed vagina, and the amount soon lessens to a trickle of bright red lochia (in the early puerperium).

If the amount of bleeding continues to be excessive and bright red, a vaginal or cervical tear may be the source. ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Maternal Physiologic Changes

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access