Chapter 49 MATERNAL AND NEWBORN CARE

The birth of a baby follows a woman’s pregnancy and the process of labour. The first part of this chapter focuses on the physiology of pregnancy and the indicators and methods of confirming pregnancy and pregnancy care, which includes preparing for the birth. Later, the four stages of labour, and nursing measures for mother and baby during the postnatal period, are explained.

PREGNANCY

Pregnancy, which is a normal physiological function, produces changes in almost all the mother’s body systems. Most of these changes are temporary and most are the result of hormone actions. These changes prepare the mother’s body to protect the developing embryo and fetus, provide for the demands of the fetus, and prepare to feed the baby when it is born. Profound endocrine changes occur that are essential for maintaining pregnancy, normal fetal growth and postpartum recovery. The hormonal factors involved in pregnancy are listed in Table 49.1.

TABLE 49.1 HORMONAL FACTORS IN PREGNANCY

| Source | Hormone | Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Ovary | Oestrogens and progesterone during the first few weeks of pregnancy | Oestrogens influence: |

| Placenta | Oestrogens and progesterone when the placenta is fully developed | Progesterone influences: |

| Placental lactogenic hormone | Promotes growth, stimulates development of the breasts and plays a role in maternal fat metabolism | |

| Relaxin | Has a relaxant effect, especially on connective tissue | |

| Pituitary | Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) | Stimulates release of thyroxine to maintain increased metabolism |

| Oxytocin | Contraction of the uterus (at the end of pregnancy). Secretion of milk (after birth) | |

| Prolactin | Initiates and sustains lactation (after baby is born) | |

| Parathyroids | Parathormone | Maintains normal calcium ion concentration |

| Adrenals | Adrenal hormones (e.g. glucocorticoids and aldosterone) | Increased secretion maintains increased metabolism |

PHYSIOLOGICAL CHANGES

Adaptation to pregnancy involves all of a woman’s body systems. The mother’s physical response is assessed in relation to normal expected alterations. Women can experience varying signs that can signify pregnancy. The maternal physiological changes during pregnancy are listed in Table 49.2.

TABLE 49.2 PHYSIOLOGICAL CHANGES IN PREGNANCY

| Area of change | Description |

|---|---|

| Uterus | A plug of mucus (the operculum) is formed by, and remains in, the cervix from the eighth week until labour begins The uterus forms into two segments; the lower segment is thinner and becomes soft and dilated towards the end of pregnancy |

| Vagina | |

| Breasts | |

| Skin | Darker pigmentation in the nipples and areolae, on the face (chloasma) and on the abdominal midline (linea nigra) |

| Musculoskeletal system | Spinal curvature changes to compensate for the abdominal enlargement, resulting in arching of the back |

| Urinary tract | |

| Gastrointestinal tract | Hormonal and mechanical changes, e.g., increased hormonal levels and reduced intestinal motility, may result in morning sickness, gastric acid reflux and constipation |

| Cardiovascular system | |

| Respiratory tract | Ventilation rate is increased to obtain the higher amounts of oxygen required |

| Basal metabolic rate (BMR) | In the second half of pregnancy, BMR increases by 15–25% to cope with the increased demands |

| Body mass | Increases by about 25% of the pre-pregnant weight. Weight gain is due to the growth of the uterus and breasts, the uterine contents, increase in maternal blood volume and interstitial fluid, and maternal storage of fats and protein |

CONFIRMATION OF PREGNANCY

The signs of pregnancy are divided into three general groups: possible, probable and positive.

Possible indicators of pregnancy

The symptoms of nausea and vomiting, which can occur at any time of the day, are often referred to as morning sickness. Nausea often occurs between 6 and 14 weeks’ gestation and is believed to be a result of large quantities of placental hormones (progesterone, oestrogen, human chorionic gonadotropin [hCG] and human placental lactogen).

Quickening is the result of fetal movement and is first perceived at 16–20 weeks’ gestation. The sensation is felt by the mother and described as gentle fluttering in the lower abdomen (Leifer 2003).

Probable indicators of pregnancy

Professional pregnancy tests based on urine or blood serum are even more reliably accurate. The most highly reliable test is the radioimmunoassay (RIA), a technique in radiology that can accurately identify pregnancy as early as 1 week after ovulation. While attributed with high levels of accuracy, pregnancy tests cannot be classed as absolutely certain indicators because there are factors that may interfere with the reliability of test results. These factors include premature menopause, the effects of taking some particular medications (anticonvulsants or anti-anxiety drugs) and the presence of a malignant tumour or haematuria (Leifer 2003).

Estimated confinement date

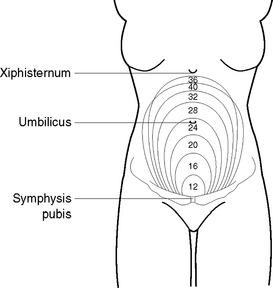

The date when the baby is due (confinement date) may be calculated by dates, the height of the uterine fundus or using ultrasound. Calculation by dates to determine the estimated due date is made by ascertaining the first day of the last known menstrual period and adding 9 months and 7 days. Calculation by assessing the fundal height (Figure 49.1) is made by measuring the height of the uterine fundus from the symphysis pubis. As the uterus enlarges steadily and predictably, the date of confinement can be determined reasonably accurately. Calculation by ultrasound is made by using height frequency, short wavelength and soundwave reflections to visualise the size of the fetus.

MINOR DISCOMFORTS ASSOCIATED WITH PREGNANCY

The pregnant woman may experience one or a variety of minor disorders or discomforts, many of which are the result of increased secretion of hormones or pressure from the uterus and its contents on other body structures. Table 49.3 lists the potential discomforts and outlines guidelines that can be used to increase women’s levels of comfort.

TABLE 49.3 CLIENT EDUCATION: MANAGEMENT OF MINOR DISCOMFORTS DURING PREGNANCY

| Discomfort | Management guidelines |

|---|---|

| Morning sickness | Small, frequent dry meals |

| Fluids in between meals | |

| Something to eat, e.g., a dry biscuit, before getting out of bed in the morning | |

| Avoid fried and heavily spiced foods | |

| Indigestion | Small frequent meals |

| Avoid spicy foods if not used to them | |

| Elevate the head of the bed | |

| Constipation | High-fibre foods |

| Adequate fluids | |

| Exercise | |

| Fainting | Avoid sudden postural changes |

| Avoid constrictive clothing | |

| Avoid lying on the back during late pregnancy | |

| Avoid fatigue | |

| Backache | Maintain correct posture |

| Daily rest periods | |

| Wear low-heeled shoes | |

| Sleep on a firm surface (e.g. place a board under the mattress) | |

| Varicose veins | Avoid long periods of standing |

| Avoid constrictive clothing | |

| Elevate the legs whenever possible | |

| Wear supportive stockings | |

| Avoid sitting or standing with the legs crossed | |

| Urinary tract infection | Adequate fluids |

| Perineal hygiene measures (e.g. wiping from front to back after elimination) | |

| Leg muscle cramps | Avoid standing for long periods |

| Elevate the legs whenever possible | |

| Relieve symptoms by pulling upwards on toes | |

| Haemorrhoids | Avoid constipation |

| Relieve discomfort by applying cold compresses or icepacks |

PRENATAL CARE AND PREPARATION

Prenatal (or antenatal) means before birth. The aims of prenatal care are to:

Because of increased public education and awareness, a woman is likely to request prenatal care as soon as she thinks she may be pregnant. Prenatal care involves physical examination of the woman, discussion and education about the importance of diet, exercise, general hygiene, preparation for labour and her expected role as a mother (Bobak & Jensen 1993).

THE INITIAL MATERNITY CONSULTATION

If pregnancy is confirmed, the obstetrician will discuss with the woman possible options regarding the birth. The woman may choose to give birth in a hospital, or in a birthing centre; she may also choose not to continue with the pregnancy (Leifer 2003).

Prenatal education may be provided by the obstetrician, midwives, or childbirth educators. The educational aspects of prenatal care are listed in Table 49.4.

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Diet | A balanced diet designed to meet the nutritional requirements of pregnancy: |

| Exercise | Moderate exercise encouraged (e.g. a daily walk or swim). Some activities (e.g. vigorous athletics) may need to be avoided if the woman has a history of abortion or premature labour |

| Rest | Fatigue should be avoided by obtaining sufficient sleep and by having numerous short rest periods during the day |

| Hygiene | Normal hygiene practices should be continued. Vaginal douching is to be avoided |

| Clothing | |

| Preparation for labour and birth | Education on childbirth and relaxation techniques are conducted on an individual or group basis by midwives, or physiotherapists. The woman’s partner is also encouraged to attend the childbirth education program, which prepares the couple for labour and birth. The classes include instruction in relaxation techniques |

| Manifestations of complications | The woman is advised to contact her obstetrician or the hospital immediately if there is: |

| Manifestations of labour | The couple are informed of the manifestations of the onset of labour: |

| Breasts | Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|