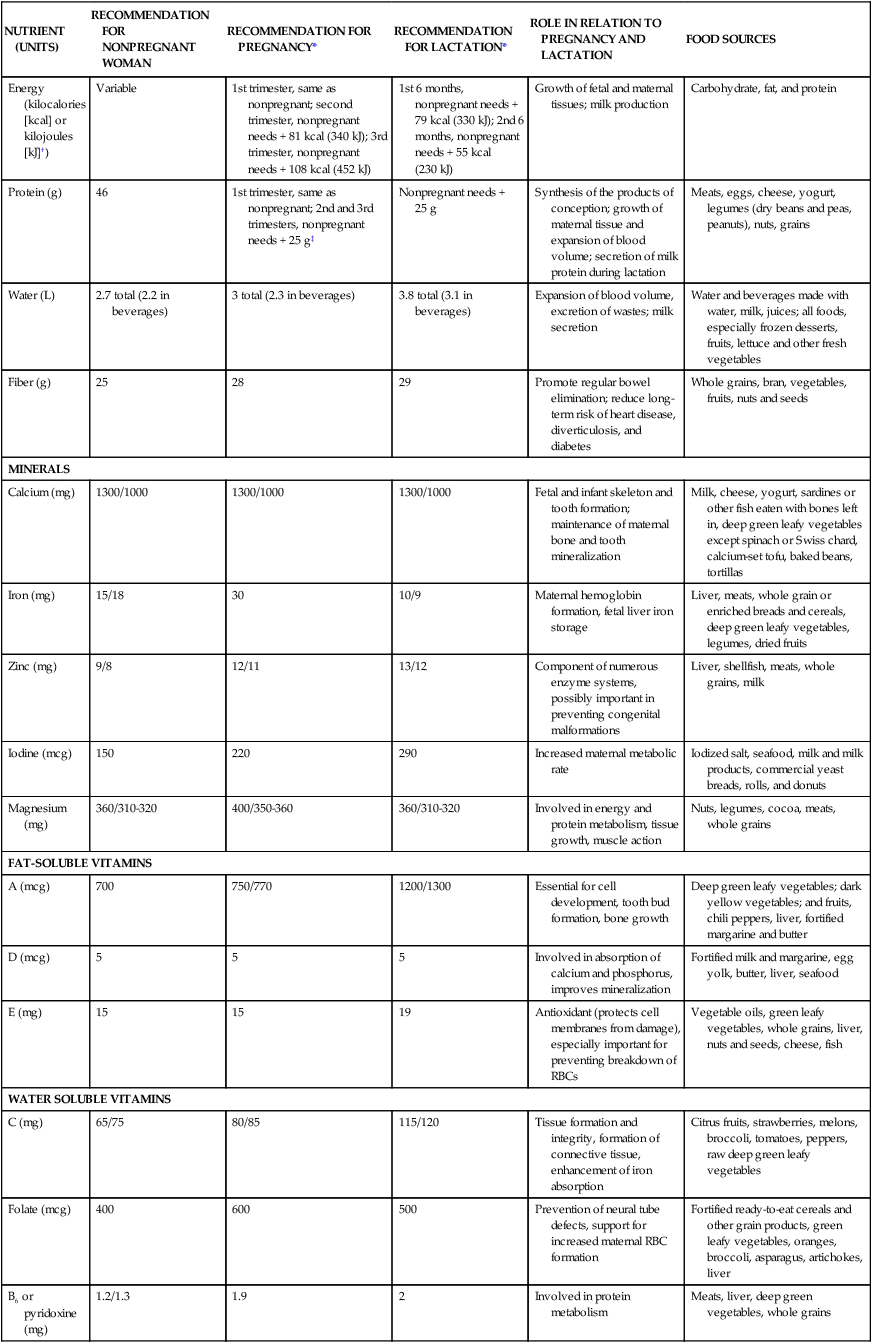

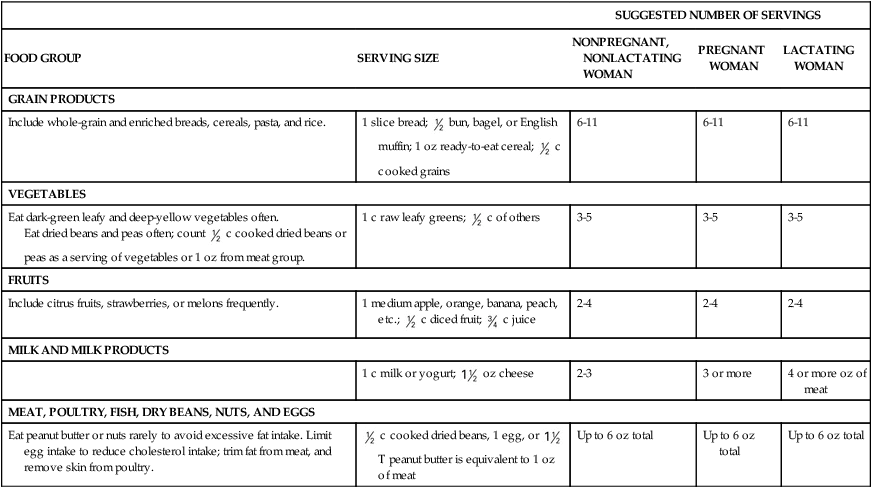

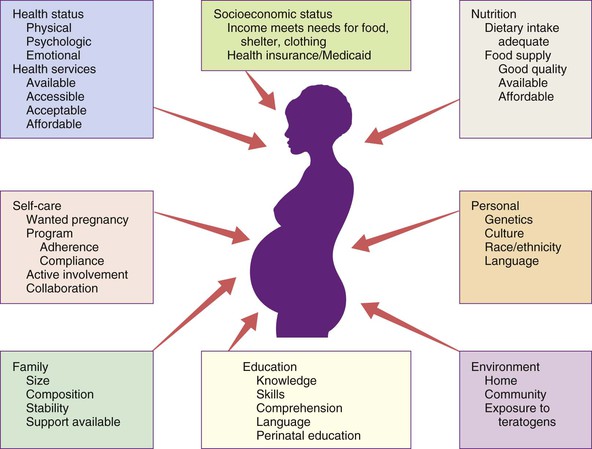

• Delineate recommended components of nutrition and dietary supplements in the preconception period. • Explain recommended maternal weight gain during pregnancy. • Compare the recommended level of intake of energy sources, protein, and key vitamins and minerals during pregnancy and lactation. • Give examples of the food sources that provide the nutrients required for optimal maternal nutrition during pregnancy and lactation. • Examine the role of nutrition supplements during pregnancy. • List five nutritional risk factors during pregnancy. • Compare the dietary needs of adolescent and mature pregnant women. • Analyze examples of cultural food patterns and possible dietary problems for two ethnic groups or for two alternative eating patterns. Additional related content can be found on the companion website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Lowdermilk/Maternity/ M aternal nutritional status at the time of conception is a significant determinant of embryonic and fetal growth (Gardiner et al., 2008) and is one of the many factors that influence the outcome of pregnancy (Fig. 8-1). Nutrition is potentially alterable, and good nutrition before and during pregnancy is an important preventive measure for a variety of problems. These problems include birth of low-birth-weight (LBW; birth weight of 2500 g or less) and preterm infants (those born before 37 weeks of gestation). The 2% of infants born very preterm (less than 32 weeks of gestation) accounted for more than one half of all infant deaths in the United States in 2005. The infant mortality rate for late preterm infants (those born between 34 0/7 and 36 6/7weeks) was more than three times that for term infants (37 to 41 weeks) (Mathews & MacDorman, 2008). Evidence is growing that the mother’s nutrition and lifestyle affect the long-term health of her children (Gardiner et al.). Thus the importance of good nutrition must be emphasized to all women of childbearing potential. Key components of nutrition care during the preconception period and pregnancy include: • Nutrition assessment that includes appropriate weight for height and adequacy and quality of dietary intake and habits • Diagnosis of nutrition-related problems or risk factors such as diabetes, phenylketonuria (PKU), and obesity • Intervention based on an individual’s dietary goals and plan to promote appropriate weight gain, ingestion of a variety of foods, appropriate use of dietary supplements, and physical activity • Evaluation as an integral part of the nursing care provided to women during the preconception period and pregnancy, with referral to a nutritionist or dietitian as necessary (Gardiner et al.) The first trimester of pregnancy is a crucial one for embryonic and fetal organ development. A healthful diet before conception is the best way to ensure that adequate nutrients are available for the developing fetus. Folate or folic acid intake is of particular concern in the periconceptual period. Folate is the form in which this vitamin is found naturally in foods, and folic acid is the form used in fortification of grain products and other foods and in vitamin supplements. Neural tube defects, or failure in closure of the neural tube, are more common in infants of women with poor folic acid intake. Researchers estimate that the incidence of neural tube defects can be decreased by as much as 70% if all women had an adequate folic acid intake during the periconceptual period (Cornel, Smit, & de Jong-van den Berg, 2005). All women capable of becoming pregnant are advised to consume 400 mcg of folic acid daily in fortified foods (e.g., ready-to-eat cereals, enriched grain products) or supplements, in addition to a diet rich in folate-containing foods such as green leafy vegetables, whole grains, and fruits (see Box 8-5 later in this chapter). The Food and Nutrition Board of the National Academy of Sciences publishes recommendations for the people of the United States, the Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) (www.iom.edu). The DRIs consist of Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) and Adequate Intakes (AIs), as well as Upper Limits (ULs), guidelines for avoiding excessive intakes of nutrients that may be toxic if consumed in excess. RDAs for some nutrients have been available for many years, and they have been revised periodically. RDAs are recommendations for daily nutritional intakes that meet the needs of almost all (97%-98%) of the healthy members of the population. AIs are similar to the RDAs and are believed to cover the needs of virtually all healthy individuals in a group, except that they deal with nutrients for which the data are insufficient to be certain of their requirements. The RDAs and AIs include a wide variety of nutrients and food components, and they are divided into age, sex, and life-stage categories (e.g., infancy, pregnancy, lactation). They can be used as goals in planning the diets of individuals (Table 8-1). TABLE 8-1 Recommendations for Daily Intakes of Selected Nutrients During Pregnancy and Lactation *When two values appear, separated by a diagonal slash, the first is for females younger than 19 years, and the second is for those 19 to 50 years of age. †The international metric unit of energy measurement is the joule (J). 1 kcal = 4.184 kJ. ‡Add an additional 25 g in twin pregnancies. Sources: Institute of Medicine. (2002). Dietary reference intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein, and amino acids. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; Institute of Medicine. (2003). Dietary reference intakes: Applications in dietary planning. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; Institute of Medicine. (2004). Dietary reference intakes for water, potassium, sodium, chloride, and sulfate. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. Energy (kilocalories or kcal) needs are met by carbohydrate, fat, and protein in the diet. No specific recommendations exist for the amount of carbohydrate and fat in the diet of the pregnant woman. However, intake of these nutrients should be adequate to support the recommended weight gain. Although protein can be used to supply energy, its primary role is to provide amino acids for the synthesis of new tissues (see the discussion later in this chapter). The estimated energy expenditure for the first trimester is the same as in the prepregnant state; during the second trimester of pregnancy the RDA is 340 kcal greater than the prepregnancy needs, and during the third trimester the amount is 462 kcal more than the prepregnant need (Institute of Medicine, 2003). Longitudinal assessment of weight gain during pregnancy is the best way to determine whether the kcal intake is adequate. Very underweight or active women or those with multifetal gestations will require more than the recommended increase in kcal to sustain the desired rate of weight gain. where the weight is in kilograms and height is in meters. Therefore for a woman who weighed 51 kg before pregnancy and is 1.57 m tall: Prepregnant BMI can be classified into the following categories: less than 18.5, underweight or low; 18.5 to 24.9, normal; 25 to 29.9, overweight or high; and greater than 30, obese (www.nhlbisupport.com/bmi/). For women with single fetuses, current recommendations are that women with a normal BMI should gain 11.3-15.9 kg during pregnancy, underweight women should gain 12.7-18.1 kg, overweight women should gain 6.8-11.3 kg, and obese women should gain 5.0-9.1 kg (Institute of Medicine, 2009). Adolescents are encouraged to strive for weight gains at the upper end of the recommended range for their BMI because the fetus and the still-growing mother apparently compete for nutrients. The risk of mechanical complications at birth is reduced if the weight gain of short adult women (shorter than 157 cm) is near the lower end of their recommended range. In twin gestations the recommended weight gain for women in the normal BMI category is 16.8 to 24.5 kg, for women who are overweight, 14.1 to 22.7 kg, and for obese women 11.3 to 19.1 kg (Institute of Medicine, 2009). The ideal weight gain for higher multiples is likely to be greater, but no specific recommendations have been issued (Malone & D’Alton, 2009). Figure-conscious women can have difficulty making the transition from guarding against weight gain before pregnancy to valuing weight gain during pregnancy. In counseling these women the nurse can emphasize the positive effects of good nutrition, as well as the adverse effects of maternal malnutrition (demonstrated by poor weight gain) on infant growth and development. This counseling includes information on the components of weight gain during pregnancy (Table 8-2) and the amount of this weight that will be lost at birth. Because lactation can help to reduce maternal energy stores gradually, this discussion provides an opportunity to promote breastfeeding. TABLE 8-2 Tissues Contributing to Maternal Weight Gain at 40 Weeks of Gestation In the United States, 20% of women who give birth are obese (Paul, 2008). However, pregnancy is not a time for weight-reduction. Even overweight or obese pregnant women need to gain at least enough weight to equal the weight of the products of conception (fetus, placenta, and amniotic fluid). If overweight women limit their caloric intake to prevent weight gain, they may also excessively limit their intake of important nutrients. Moreover, dietary restriction results in catabolism of fat stores, which, in turn, augments the production of ketones. The long-term effects of mild ketonemia during pregnancy are not known, but ketonuria has been found to be correlated with the occurrence of preterm labor. The idea that the quality of the weight gain is important should be stressed to obese women (and to all pregnant women), with emphasis placed on the consumption of nutrient-dense foods and the avoidance of empty-calorie foods. Weight gain is important, but pregnancy is not an excuse for uncontrolled dietary indulgence. Excessive weight gained during pregnancy may be difficult to lose after pregnancy, thus contributing to chronic overweight or obesity, an etiologic factor in a host of chronic diseases, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and arteriosclerotic heart disease. The woman who gains 18 kg or more during pregnancy is especially at risk (Box 8-1 and the Critical Thinking/Clinical Decision Making Box). Milk, meat, eggs, and cheese are complete-protein foods with a high biologic value. Legumes (dried beans and peas), whole grains, and nuts are also valuable sources of protein. In addition, these protein-rich foods are a source of other nutrients such as calcium, iron, and B vitamins; plant sources of protein often provide needed dietary fiber. The recommended daily food plan (Table 8-3) is a guide to the amounts of these foods that would supply the quantities of protein needed. The recommendations provide for only a modest increase in protein intake over the prepregnant levels in adult women. TABLE 8-3 Daily Food Guide for Pregnancy and Lactation No adverse effects on the normal mother or fetus have been found with the use of aspartame (NutraSweet, Equal), acesulfame potassium (Sunett), and sucralose (Splenda), artificial sweeteners commonly used in low- or no-calorie beverages and low-calorie food products. Aspartame, which contains phenylalanine, should be avoided by the woman with PKU (Box 8-2). Stevia (stevioside) is a food additive used as a sweetener but it has not been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for that purpose. In general, the nutrient needs of pregnant women, except perhaps the need for folate and iron, can be met through dietary sources. Counseling about the need for a varied diet rich in vitamins and minerals should be a part of every pregnant woman’s early prenatal care and should be reinforced throughout pregnancy. Supplements of certain nutrients (listed in the following discussion) are recommended whenever the woman’s diet is very poor or whenever significant nutritional risk factors are present. Nutritional risk factors in pregnancy are listed in Box 8-3.

Maternal and Fetal Nutrition

Web Resources

![]()

Nutrient Needs Before Conception

Nutrient Needs During Pregnancy

NUTRIENT (UNITS)

RECOMMENDATION FOR NONPREGNANT WOMAN

RECOMMENDATION FOR PREGNANCY*

RECOMMENDATION FOR LACTATION*

ROLE IN RELATION TO PREGNANCY AND LACTATION

FOOD SOURCES

Energy (kilocalories [kcal] or kilojoules [kJ]†)

Variable

1st trimester, same as nonpregnant; second trimester, nonpregnant needs + 81 kcal (340 kJ); 3rd trimester, nonpregnant needs + 108 kcal (452 kJ)

1st 6 months, nonpregnant needs + 79 kcal (330 kJ); 2nd 6 months, nonpregnant needs + 55 kcal (230 kJ)

Growth of fetal and maternal tissues; milk production

Carbohydrate, fat, and protein

Protein (g)

46

1st trimester, same as nonpregnant; 2nd and 3rd trimesters, nonpregnant needs + 25 g‡

Nonpregnant needs + 25 g

Synthesis of the products of conception; growth of maternal tissue and expansion of blood volume; secretion of milk protein during lactation

Meats, eggs, cheese, yogurt, legumes (dry beans and peas, peanuts), nuts, grains

Water (L)

2.7 total (2.2 in beverages)

3 total (2.3 in beverages)

3.8 total (3.1 in beverages)

Expansion of blood volume, excretion of wastes; milk secretion

Water and beverages made with water, milk, juices; all foods, especially frozen desserts, fruits, lettuce and other fresh vegetables

Fiber (g)

25

28

29

Promote regular bowel elimination; reduce long-term risk of heart disease, diverticulosis, and diabetes

Whole grains, bran, vegetables, fruits, nuts and seeds

MINERALS

Calcium (mg)

1300/1000

1300/1000

1300/1000

Fetal and infant skeleton and tooth formation; maintenance of maternal bone and tooth mineralization

Milk, cheese, yogurt, sardines or other fish eaten with bones left in, deep green leafy vegetables except spinach or Swiss chard, calcium-set tofu, baked beans, tortillas

Iron (mg)

15/18

30

10/9

Maternal hemoglobin formation, fetal liver iron storage

Liver, meats, whole grain or enriched breads and cereals, deep green leafy vegetables, legumes, dried fruits

Zinc (mg)

9/8

12/11

13/12

Component of numerous enzyme systems, possibly important in preventing congenital malformations

Liver, shellfish, meats, whole grains, milk

Iodine (mcg)

150

220

290

Increased maternal metabolic rate

Iodized salt, seafood, milk and milk products, commercial yeast breads, rolls, and donuts

Magnesium (mg)

360/310-320

400/350-360

360/310-320

Involved in energy and protein metabolism, tissue growth, muscle action

Nuts, legumes, cocoa, meats, whole grains

FAT-SOLUBLE VITAMINS

A (mcg)

700

750/770

1200/1300

Essential for cell development, tooth bud formation, bone growth

Deep green leafy vegetables; dark yellow vegetables; and fruits, chili peppers, liver, fortified margarine and butter

D (mcg)

5

5

5

Involved in absorption of calcium and phosphorus, improves mineralization

Fortified milk and margarine, egg yolk, butter, liver, seafood

E (mg)

15

15

19

Antioxidant (protects cell membranes from damage), especially important for preventing breakdown of RBCs

Vegetable oils, green leafy vegetables, whole grains, liver, nuts and seeds, cheese, fish

WATER SOLUBLE VITAMINS

C (mg)

65/75

80/85

115/120

Tissue formation and integrity, formation of connective tissue, enhancement of iron absorption

Citrus fruits, strawberries, melons, broccoli, tomatoes, peppers, raw deep green leafy vegetables

Folate (mcg)

400

600

500

Prevention of neural tube defects, support for increased maternal RBC formation

Fortified ready-to-eat cereals and other grain products, green leafy vegetables, oranges, broccoli, asparagus, artichokes, liver

B6 or pyridoxine (mg)

1.2/1.3

1.9

2

Involved in protein metabolism

Meats, liver, deep green vegetables, whole grains

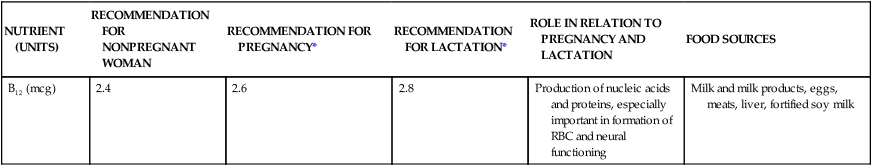

B12 (mcg)

2.4

2.6

2.8

Production of nucleic acids and proteins, especially important in formation of RBC and neural functioning

Milk and milk products, eggs, meats, liver, fortified soy milk

Energy Needs

Weight gain

Pattern of weight gain

Hazards of restricting adequate weight gain

TISSUE

KILOGRAMS

POUNDS

Fetus

3.0-3.9

7.0-8.5

Placenta

0.9-1.1

2.0-2.5

Amniotic fluid

0.9

2

Increase in uterine tissue

0.9

2

Breast tissue

0.5-1.8

1-4

Increased blood volume

1.8-2.3

4-5

Increased tissue fluid

1.4-2.3

3-5

Increased stores (fat)

1.8-2.7

4-6

Protein

SUGGESTED NUMBER OF SERVINGS

FOOD GROUP

SERVING SIZE

NONPREGNANT, NONLACTATING WOMAN

PREGNANT WOMAN

LACTATING WOMAN

GRAIN PRODUCTS

Include whole-grain and enriched breads, cereals, pasta, and rice.

1 slice bread;  bun, bagel, or English muffin; 1 oz ready-to-eat cereal;

bun, bagel, or English muffin; 1 oz ready-to-eat cereal;  c cooked grains

c cooked grains

6-11

6-11

6-11

VEGETABLES

Eat dark-green leafy and deep-yellow vegetables often.

Eat dried beans and peas often; count  c cooked dried beans or peas as a serving of vegetables or 1 oz from meat group.

c cooked dried beans or peas as a serving of vegetables or 1 oz from meat group.

1 c raw leafy greens;  c of others

c of others

3-5

3-5

3-5

FRUITS

Include citrus fruits, strawberries, or melons frequently.

1 medium apple, orange, banana, peach, etc.;  c diced fruit;

c diced fruit;  c juice

c juice

2-4

2-4

2-4

MILK AND MILK PRODUCTS

1 c milk or yogurt;  oz cheese

oz cheese

2-3

3 or more

4 or more oz of meat

MEAT, POULTRY, FISH, DRY BEANS, NUTS, AND EGGS

Eat peanut butter or nuts rarely to avoid excessive fat intake. Limit egg intake to reduce cholesterol intake; trim fat from meat, and remove skin from poultry.

c cooked dried beans, 1 egg, or

c cooked dried beans, 1 egg, or  T peanut butter is equivalent to 1 oz of meat

T peanut butter is equivalent to 1 oz of meat

Up to 6 oz total

Up to 6 oz total

Up to 6 oz total

Fluids

Minerals and Vitamins

oz)

oz) oz)

oz) cup)

cup) cup)

cup) -1 cup)

-1 cup) cup)

cup) cup)

cup) cup)

cup) cup)

cup)