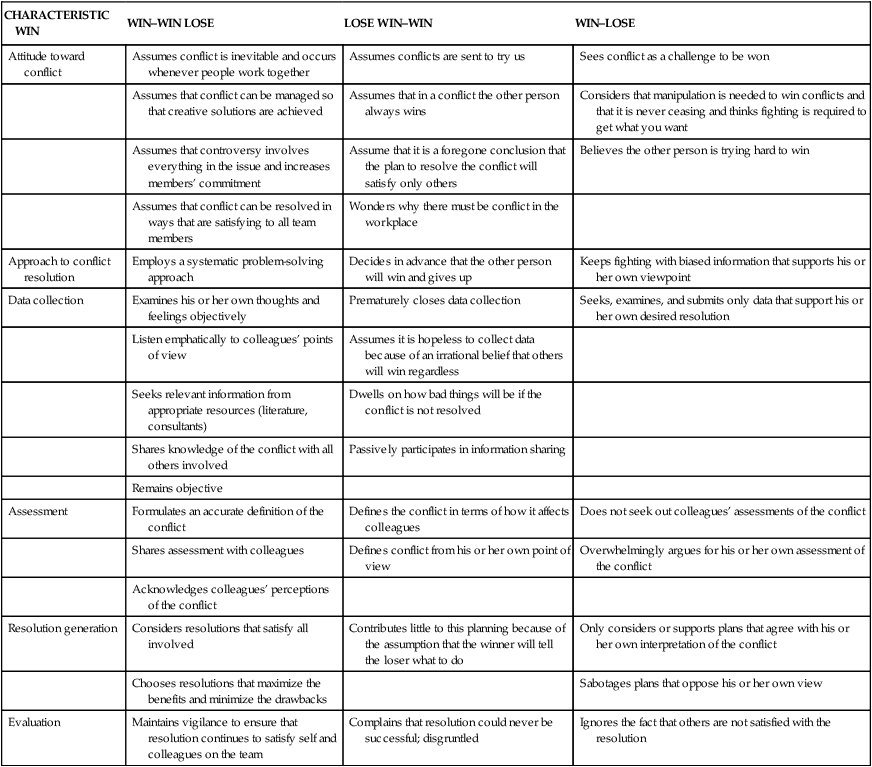

Chapter 28 2. Identify four categories of conflict 3. Identify the steps of win–win conflict resolution 4. Contrast win–win, lose–win, and win–lose methods of handling team conflict 5. Identify the characteristics of multigenerational team members and their impact on the team 6. Participate in selected exercises to build assertive conflict-resolution skills Conflict can be a source of personal and organizational stress by the very nature of nurses’ work (Vivar, 2006). Conflict, often seen as “bad,” is a natural part of interactions and, when effectively addressed, improves interpersonal relationships and can promote organizational growth (Chadwick, 2010). A longitudinal study of 53 college student teams indicated that conflict management “has a direct, positive effect on team cohesion and moderates the relationship between relationship conflict and team cohesion as well as that between task conflict and team cohesion” (Tekleab et al, 2009, p. 170). Conflict may be viewed as a feeling, a disagreement, a real or perceived incompatibility of interests, inconsistent worldviews, or a set of behaviors (Mayer, 2000). Conflict arises when interdependency exists, and conflict resolution is necessary to build positive relationships with others as well as to meet our own needs. Whenever two people come together, there is the potential for conflict. Conflict can occupy 30% of a manager’s time (Marick and Albright, 2002). Although conflict is inevitable, it can have advantageous outcomes when it is handled in assertive and responsible ways. Conflict resolution can build interdependence and professional collaboration and help team members better address the big-picture issues. Building positive co-worker relationships, teamwork, and collaboration supports clear communication, which has a direct impact on patient safety. The integration of communication skills and teamwork training in schools of nursing and in the workplace supports this effort (Beckett and Kipnis, 2009; Chapman, 2009; Clark, 2009; Corless et al, 2009; McKeon et al, 2009; Thomas, 2009). The Institute of Medicine’s report on medical errors concluded that “as many as 98,000 people die yearly in the United States because of preventable medical errors . . . a startling 70% of these preventable medical errors result from poor communication between healthcare providers” (Kohn et al, 2000, as cited in Lamontagne, 2010, p. 54). The Joint Center for Transforming Healthcare (Zhani, 2010) reports an “estimated 80% of serious medical errors involve miscommunication between caregivers when responsibility for patients is transferred or handed-off.” In their Hand-off Communication Project participating hospitals found that more than 37% of hand-offs were defective, preventing the receiver of the information from safely caring for the patient. After implementing targeted solutions to the hand-off communication, the result was a 52% reduction in defective hand-offs. Cushnie (1988) identifies four categories of conflict intensifying in degree of difficulty from first to last: facts, methods, goals, and values. Differences in belief systems are the most complex type of conflict, and a high level of motivation is required from involved parties to understand each other’s beliefs. If the parties can avoid the divisiveness of allocating others’ viewpoints to rigid categories of “right” or “wrong” and find compatible goals, they are on their way to conflict management (Cushnie, 1988). Several forms of conflict are seen (Kinder, 1981): • Intrapersonal conflict occurs within an individual. • Interpersonal conflict occurs between two individuals or among members of a group. • Intragroup conflict occurs within an established group. This chapter focuses on interpersonal conflict in a workplace or school setting. Team members often have different (or opposing) ideological views about a given situation. Their views may come from having different objectives or from endorsing different priorities among the objectives. Conflict results when team members do not agree on what to do, how to do it, and when to do it. Review Chapter 5 for the stages of group behavior. Remember that group conflict is healthy and expected in the storming stage. Resolving a conflict means acting in such a way that an agreement is reached that is acceptable, and even pleasing, to both parties. If both parties cannot agree on a resolution, the conflict will continue. When conflict drags out and team members do not see a hopeful resolution, then helplessness prevails. Any healthcare team that is stuck in this hopeless situation is not working at its full capacity. Harrington-Mackin (1994) advises dealing with conflicts in a timely way and suggests that most people find it difficult to openly discuss and work through conflicts. Instead, they accumulate grudges and use techniques such as procrastination and sniping to “get even.” Client care and morale suffer when conflicts remain unresolved. A win–win conflict management strategy covers each of the following steps (Flanagan, 1995): 1. View the problem in terms of needs (what is required) instead of solutions (what should be done) to facilitate a mutual problem-solving approach; detach yourself from biases and stay focused on the actual data. 2. Consider the problem as a mutual one to be solved, requiring the active involvement of all affected persons. 3. Describe the conflict as specifically as possible, using undistorted data. 4. Identify the differences between concerned parties before attempting to resolve the conflict. 5. See the conflict from another point of view. 6. Use brainstorming to arrive at possible solutions instead of adopting the first or most convenient idea. 7. Select the solution that best meets both parties’ needs and considers all possible consequences. 8. Reach an agreement about how the conflict is to end and not recur. 9. Plan who will do what and where and when it will be done. 10. After the plan has been implemented, evaluate the problem-solving process and review how well the solution turned out. Table 28-1 summarizes three different approaches to conflict. The assertive, responsible attitude toward conflict and approach to conflict resolution is contrasted with the nonassertive, irresponsible approaches. Table 28-1 Assertive/Responsible versus Nonassertive/Irresponsible Ways of Handling Team Conflict 1. Before you can do anything to resolve a conflict, you need to fully understand the conflict, including your own thoughts and feelings about the situation as well as the thoughts of your colleagues. If you try to resolve a conflict without completing an assessment, you will probably overlook an important factor that could result in an unsatisfactory resolution. 2. To fully understand your side of the conflict, you need to examine your own thoughts and feelings. You cannot complete this step in a hurry. You need to sit down (with paper and pencil if necessary) and discover your answers to the following questions: In considering the conflict you might have some of the following thoughts: • “It bothers me that clients are not warned about side effects that might result from the medications.” • “It’s not right that they don’t have full knowledge of the treatment and that they are taking the pills without fully understanding the implications.” • “I believe that it is dishonest to withhold information about side effects from clients.” • “I believe that people have the responsibility to decide what they should do about their health. By withholding information, we are keeping the control of clients’ health in our hands.” Our initial reaction to a conflict situation is often influenced more by emotion than by intellect. The tension or anxiety creates a fight-or-flight stress response, and the intensity of the stress response varies in relation to the degree of threat perceived (Cushnie, 1988). Taking time to sort out your emotional reactions as you just did helps you control your emotions and increases your effectiveness in conflict management.

Managing team conflict assertively and responsibly

Definition of conflict

Values

Conflict-resolution approaches

CHARACTERISTIC WIN

WIN–WIN LOSE

LOSE WIN–WIN

WIN–LOSE

Attitude toward conflict

Assumes conflict is inevitable and occurs whenever people work together

Assumes conflicts are sent to try us

Sees conflict as a challenge to be won

Assumes that conflict can be managed so that creative solutions are achieved

Assumes that in a conflict the other person always wins

Considers that manipulation is needed to win conflicts and that it is never ceasing and thinks fighting is required to get what you want

Assumes that controversy involves everything in the issue and increases members’ commitment

Assume that it is a foregone conclusion that the plan to resolve the conflict will satisfy only others

Believes the other person is trying hard to win

Assumes that conflict can be resolved in ways that are satisfying to all team members

Wonders why there must be conflict in the workplace

Approach to conflict resolution

Employs a systematic problem-solving approach

Decides in advance that the other person will win and gives up

Keeps fighting with biased information that supports his or her own viewpoint

Data collection

Examines his or her own thoughts and feelings objectively

Prematurely closes data collection

Seeks, examines, and submits only data that support his or her own desired resolution

Listen emphatically to colleagues’ points of view

Assumes it is hopeless to collect data because of an irrational belief that others will win regardless

Seeks relevant information from appropriate resources (literature, consultants)

Dwells on how bad things will be if the conflict is not resolved

Shares knowledge of the conflict with all others involved

Passively participates in information sharing

Remains objective

Assessment

Formulates an accurate definition of the conflict

Defines the conflict in terms of how it affects colleagues

Does not seek out colleagues’ assessments of the conflict

Shares assessment with colleagues

Defines conflict from his or her own point of view

Overwhelmingly argues for his or her own assessment of the conflict

Acknowledges colleagues’ perceptions of the conflict

Resolution generation

Considers resolutions that satisfy all involved

Contributes little to this planning because of the assumption that the winner will tell the loser what to do

Only considers or supports plans that agree with his or her own interpretation of the conflict

Chooses resolutions that maximize the benefits and minimize the drawbacks

Sabotages plans that oppose his or her own view

Evaluation

Maintains vigilance to ensure that resolution continues to satisfy self and colleagues on the team

Complains that resolution could never be successful; disgruntled

Ignores the fact that others are not satisfied with the resolution

Assertive and responsible ways to overcome conflict

Conflict situation involving the whole healthcare team

What is it about this conflict that bothers me?

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Managing team conflict assertively and responsibly

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access