15 Managing symptoms

assess, plan, implement and evaluate

Introduction

In any clinical setting you will have the potential to care for a person with a cancer diagnosis who is experiencing one or more of the distressing symptoms explored in this chapter. By engaging in the exercises for each symptom, you are given the opportunity to consider how the symptom can be managed in any specific placement. It is important to apply the principles of assessment and holistic care of a patient introduced below. Patient care must also take into consideration the cultural and ethnic needs of patients and family members. These are explored in more detail in the Chapter 16, however it is important to start to consider the implications as you develop cultural competence in symptom management. This chapter explores some of the principles in supporting a patient with a cancer diagnosis who is experiencing one or more distressing symptom. This can happen during treatment for the cancer, as well as if the patient is in the palliative care stage of the illness. Some symptoms can continue after the patient has completely recovered from the cancer. For example, fatigue or taste changes can sometimes occur following chemotherapy or radiotherapy and may last for many years. Sometimes symptoms can occur as ‘acute events’ and need to be dealt with swiftly. These include hypercalcaemia and spinal cord compression.

The principles of assessment

The nursing process (Roper et al 2000) suggests assessment is the ‘first step’ in the four-step cycle of planning, implementing and evaluating care. Uys and Habermann (2005) recognise the importance of collecting information in the assessment process, while Holland et al (2008) refer to assessment as a ‘cyclical activity’ that includes collecting and reviewing information and linking this assessment to impact on activities of living.

Remember, the information we gather includes that from the patient, family and professional teams.

The principles of planning care

When we have gathered information about a patient, we are then able to plan the care we are going to provide. It is important that any information is clarified and communicated with wider team members in an appropriate way. Remember that any information we have about a patient is confidential and must be respected and kept safe at all times. The NMC code of conduct (NMC 2008) states confidentiality as a patient’s right so, as you gather information, it is important to inform patients how this will be used. Doing this shows the patient respect.

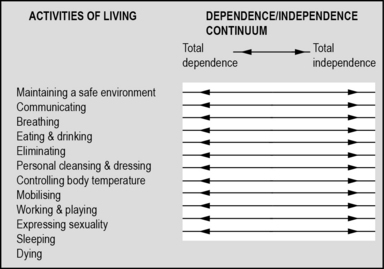

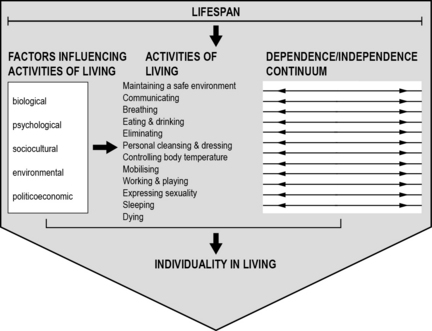

One way to collate this information in a logical and holistic way is by using the Roper, Logan and Tierney model (Roper et al 2000) (Figs 15.1 and 15.2). This model was originally developed in 1980 by Nancy Roper and published under the title The Elements of Nursing and is a collection of core themes around activities of living. They were developed with the idea that activities of living can be applied to patients in any clinical area, are patient focused and can give a clear idea of the needs of a patient and their family at any point in time. You may have already seen this model used in a previous practice placement. Sometimes they are referred to as the activities of daily living (ADLs). Admission assessment forms for both acute hospitals and community settings are often based on this model.

There are 12 activities of living which take a holistic approach:

1. Maintaining a safe environment.

6. Personal cleansing and dressing.

7. Controlling body temperature.

These activities of living are not separate themes but are linked through biological, psychosocial and political factors. Each of the activities are interlinked and will impact on a person’s degree of dependence or independence (Holland et al 2008).

Gathering information about a patient and their family is not easy. There are many things that can hinder the effective collection of data and this can have a direct impact on the care given or understanding of what the priority needs are for a patient and their family. Information can be gathered about a patient at admission (part 1). If the patient dies, part 2 can be completed about what happened at the time of death and how the family reacted. This information can help with planning ongoing bereavement support (See Appendix 2).

Read through the following scenario and consider the information you have about the patient:

You are helping to care for a man who has been admitted from another ward in the hospital and you have been invited to go with the staff nurse on the ward round.

You are helping to care for a man who has been admitted from another ward in the hospital and you have been invited to go with the staff nurse on the ward round.

In this morning’s evaluation of patient care, the following has been written by the night staff:

In this morning’s evaluation of patient care, the following has been written by the night staff:

The doctor says to the patient, ‘I hear you are not sleeping’. The patient answers ‘No Doctor’.

The doctor says to the patient, ‘I hear you are not sleeping’. The patient answers ‘No Doctor’.

On the ward round, the doctors discuss a prescription for sleeping tablets.

On the ward round, the doctors discuss a prescription for sleeping tablets.

On the activities of living admission sheet, the following is written:

On the activities of living admission sheet, the following is written:

You were on a late shift last night and overheard a conversation between this patient and the waitress who was serving the evening drinks:

You were on a late shift last night and overheard a conversation between this patient and the waitress who was serving the evening drinks:

Consider the information we have about this patient, his sleep pattern and his current needs.

Here is a list of what we already know about the patient:

1. He has a long-term sleep pattern that has not changed for several years.

2. He is open with this information with some members of the care team.

3. He appears reluctant to freely offer information to the doctor.

4. Having a cup of tea in the night seems to help him feel settled.

Where can other information be found?

1. Admission notes from his previous ward and possible previous admissions.

2. A conversation with the patient to ask what his sleep pattern means to him. Is it a problem? What helps?

1. Is he waking because it is his normal routine?

2. Is he waking because he is in a new environment?

3. Is he waking because he is in pain or experiencing another form of distress?

The principles of managing common symptoms experienced by cancer and palliative care patients

• Communication: this includes the information gathering phase and involves how information about the patient is communicated with the patient as well as other members of the care team. Understanding what the key issues are, discussing treatment options and communicating options is the first stage in ensuring care planned considers all the important factors that are relevant to the patient.

• Choice: giving information to the patient about what is happening is essential for the patient to make an informed choice about treatment. This includes the concept of consent and is one of the underpinning ethical principles of autonomy. To refresh your knowledge of ethical principles, go back to Chapter 5. If patients feel they have choices in their treatment regimen, they are more likely be compliant with taking medication, attending appointments, etc. For example, if a patient understands the link between a specific medication and risk of constipation, they are more likely to take the prescribed laxatives.

• Care: this must be planned, holistic and patient centred. Attention to detail is vital. Care must be continually evaluated by all members of the multidisciplinary team, documented and then renegotiated with the patient and family. Always consider the needs of patients.

Under each of the ‘three C’ headings, list all the activities you can undertake as a nurse to ensure principles of symptom management are achieved. To help you do this, reflect back on the observations you have made in current and previous placements. To refresh your knowledge of the principles of assessment, go back to page 129.

Good symptom management relies on an effective assessment process.

Pain: causes, assessment and management

A universally accepted definition of pain is that it is an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience that is associated with actual or potential tissue damage (International Association for the Study of Pain 2007). Pain is complex and understanding what is both initiating the pain and maintaining it is important for effective management. Chapter 5 on palliative care introduced you to the concept of ‘total pain’. The contemporary way of referring to total pain is from a ‘biopsychosocial’ perspective (Holdcroft & Power 2003) and can be divided into three factors:

1. The person – includes biological and psychological influences.

2. Type of disease – includes past history and present disease.

3. Environment – includes cultural expectations, upbringing, roles, lifestyle.

The most challenging part of managing pain is the subjectivity of pain; what it means to one person is different from another person, as is the individual’s ability to manage the pain. ‘Pain is whatever the person experiencing it says it is, existing whenever he says it does’ (McCaffery 1968:95). While this work of McCaffery is old, it continues to be a fundamental principle of pain management.

1. Transduction – involves the process of converting mechanical, thermal or chemical noxious or painful stimulus into a nervous impulse.

2. Transmission – involves the nervous impulse being conducted by sensory nerves to the central nervous system. Different nerves carry different impulses.

3. Perception – conscious perception of pain is perceived by an individual once all the incoming nervous messages are interpreted by the brain.

4. Modulation – throughout the process, various physiological and psychological mechanisms can adjust the nociceptive message to either increase or decrease the pain experienced.

Re-read the notes you made about your personal experiences of pain on page 39. Now consider how you might know a patient is in pain. Make a list of the words that a person might use to describe pain followed by a list of the behaviours you might observe. Consider how this information might have been gathered and be documented in the patient’s case notes and communicated across the care team.

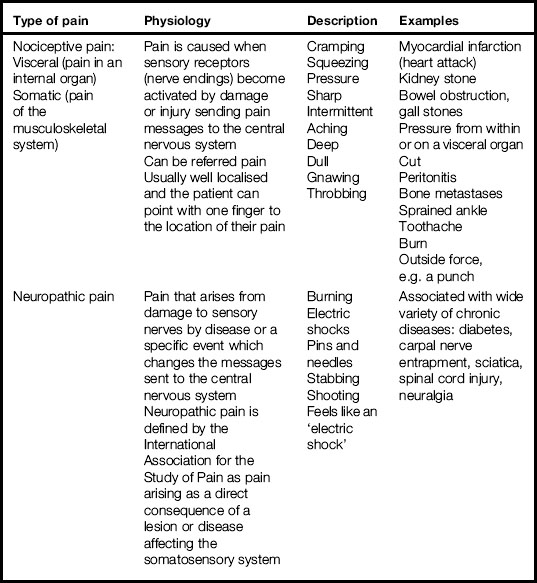

Types of pain

Table 15.1 gives a simple overview of two types of pain, the basic physiology and words associated with how pain might be experienced.

Using Table 15.1, write a few sentences about the impact the different types of pain can have on the activities of living.

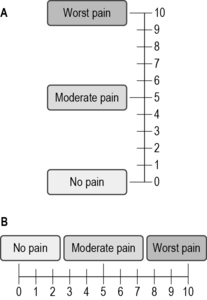

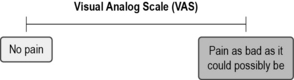

Assessing pain correctly is fundamental to ensuring analgesia prescribed is appropriate and effective. Asking how the pain is and getting the patient to describe the pain is a useful way to establish possible causes. Also finding out what makes it worse and what makes it better is important too. The assessment tool in Figure 15.3 is called the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) and is used in many clinical areas and is a quick way to explore pain with a patient.

Fig 15.3 Pain assessment tool

(reproduced with permission from McCaffery M, Pasero C (1999) Pain, clinical manual, 2nd edn. Mosby, St Louis)

Management of pain

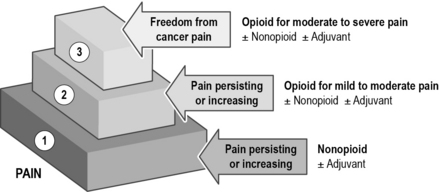

The World Health Organisation (WHO) analgesic step ladder is shown in Figure 15.4. Here we can see that analgesia is staged from a non-opioid, to a weak opioid and then to a strong opioid. This is the recommended ladder by which analgesia is prescribed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree