CHAPTER FOURTEEN Managing finances in the nursing practice setting

INTRODUCTION

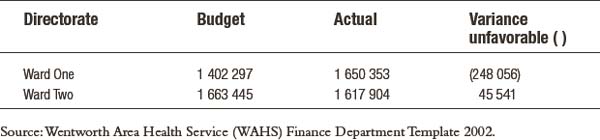

The most appropriate level to identify and manage costs is at point of expenditure. It is at the ward or facility level that this expenditure occurs. Nurses incur most clinical expenses as they care for their patients/clients. An administrative requirement for managers is the ability to prioritise expenditure according to available money. The financial practices at work are no different from the financial management expertise required in your personal life. For example, matching the money you are paid each week with the expenses you incur means that if you are paid $500 per week and your rent is $250 per week, there is $250 to spend on food or other items. This simplistic example is mirrored in Table 14.1 below. The first two columns identify the budget and the actual expenses incurred. The third column provides details of the variance between the money allocated and expended. This example highlights that Ward One had a negative variance while the expenditure of Ward Two was less than budgeted.

It is necessary to ensure that management objectives (that is, the organisation’s strategic plan) form the basis of financial planning at the ward/unit level. If the nurse manager’s perception of what the ward’s or unit’s objectives, throughput and outcomes are, does not align with the organisation’s goals and objectives, it becomes impossible to achieve financial balance and harmony. This can be quite complicated because in a way, the nurse manager is expected to predict the future. And of course, this can be difficult to do with any degree of accuracy (Jopling et al. 1998).

PRINCIPLES OF FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT

The principles associated with financial management are based on accounting and budgeting. These are the financial or monetary quantification of the goals and objectives of the organisation. Budgeting is the management tool used to plan and control the expending of finances, while accounting is the process of recording, classifying, interpreting and reporting financial data to provide a source of financial information (Levy 1985).

Budgeting

Budgeting is a tool for planning, monitoring and controlling costs. It is part of a suite of management tools used in association with other management functions such as planning and controlling. Once the goals of the organisation have been identified, budgeting ensures that they are met by allocating money to them (Rowland & Rowland 1985). The stages of budgeting include:

The next stage of budgeting is the comparison of the budgeted costs with the actual expenditure. Table 14.1 demonstrates this comparison.

The differences between the two results—those planned and the actual results—need to be examined closely. There is a natural tendency not to worry about a favourable result and to only be concerned about an unfavourable one. However, any deviation from the expected outcome warrants assessment. This review is necessary because if the budget plan reflects the actual activity and costs, then the result should not be favourable and may reflect a problem with the accounting process, for example, an invoice that may not have been paid. Reasons for unfavourable results also require examination and may include an increase in patient activity (e.g. more patients than planned), an increase in costs (e.g. disposable goods such as gauze squares significantly rise in price once the budget has been set), or there is a change in casemix (e.g. the acuity or complexity of care required for patients increases or the ward commences treating medical patients and changes its role to an oncology ward).

PROCESSES FOR MANAGING FINANCES

When building a budget it is necessary to identify what is included within it and what services the budget actually encompasses. Historically, organisations were managed centrally with finance departments controlling the allocation and approval functions. Budgets were not devolved to ward or unit levels. However, as hospitals and other health care institutions have become more complex and clinicians have demanded greater control over health care finance, devolution of financial responsibility has occurred in many clinical settings. With this transfer, other models of health funding and budgeting have evolved, including output-based, which allows for more accurate assessment of costs associated with individual patients for a specific episode of care (Gordon & Clout 2002).

Types of costs

Costs associated with the delivery of care provided in health fall under four main cost concepts of:

Fixed and variable costs relate to the activity of the organisation. The activity may be measured in patient days, level of acuity, number of presentations, number of operations or number of meals. Fixed costs remain the same regardless of the level of activity within the cost centre. Examples of fixed costs include contracts for servicing equipment that may be in place for a specific period of time, such as five years, and lease arrangements for equipment. Variable costs are directly linked with the activity of the organisation. The individual cost per unit may not change but the costs will rise as more is undertaken. For example, if the hourly rate of a nurse is $20 and each nurse cares for five patients, the hourly nursing costs for ten patients would be $40, and for 20 patients the cost would be $80 (Courtney 1998).

When identifying budgets it is important to understand some basic economic terms. Opportunity cost in economic terms is seen as the cost of the best alternative foregone (McTaggart et al. 1996). When developing a budget it is necessary for nurse managers to use their management skills to consider opportunity costs in their decision-making. This is useful in a workplace where there are limited resources and managers need to make choices between purchasing different consumables and using more creative staffing methods. Another way to consider this issue is to ask the question, ‘With my known fixed budget, is it more important to purchase item X or item Y?’

Nurse managers make these types of decisions on a regular basis with money that has been donated—should a new piece of equipment be purchased or the donation used to provide extra training for staff? Or should a replacement monitor be purchased with the knowledge that the existing one has passed its expected economic life span but is still functioning, or should this money be used to purchase the ward’s first computer, which could be used by staff and for patient education, as well as statistical collection. In each of these examples there is no clear answer. The actual decision made will depend upon the local circumstances, including the origin or source of the funds, the delegated authority of the manager and the relative importance of the choices in the local environment (Gordon & Clout 2002, p.4).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree