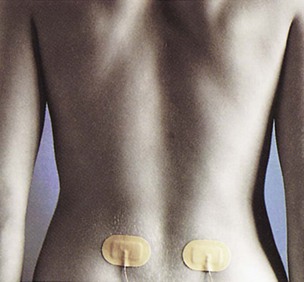

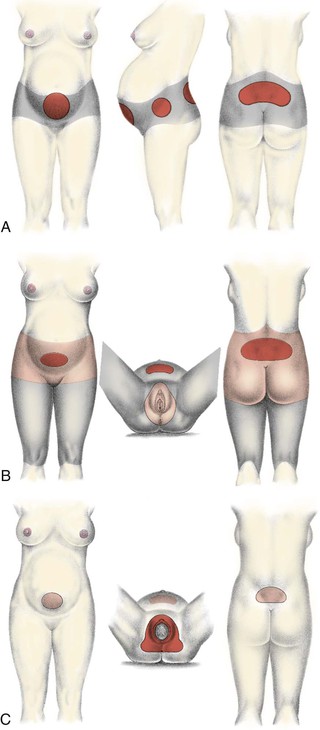

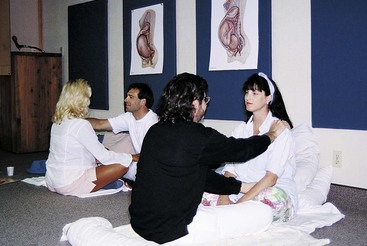

• Describe breathing and relaxation techniques used for each stage of labor. • Identify nonpharmacologic strategies to enhance relaxation and decrease discomfort during labor. • Compare pharmacologic methods used to relieve discomfort in different stages of labor and for vaginal or cesarean births. • Discuss the use of naloxone (Narcan). • Apply the nursing process to the management of the discomfort of a woman in labor. • Summarize the nursing responsibilities appropriate for a woman receiving analgesia or anesthesia during labor. Additional related content can be found on the companion website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Lowdermilk/Maternity/ • Critical Thinking Exercise: Patient Receiving Epidural Block • Nursing Care Plan: Epidural Block during Labor • Nursing Care Plan: Nonpharmacologic Management of Discomfort P ain is an unpleasant, complex, highly individualized phenomenon with both sensory and emotional components. Pregnant women commonly worry about the pain they will experience during labor and birth and how they will react to and deal with that pain. Many physiologic, emotional, psychosocial, and environmental factors influence the nature and degree of pain experienced by the laboring woman and how she will respond to and cope with the pain (Zwelling, Johnson, & Allen, 2006). A variety of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic methods can help the woman or the couple cope with the discomfort of labor. The methods selected depend on the situation, availability, and the preferences of the woman and her health care provider. The pain and discomfort of labor have two origins, visceral and somatic. During the first stage of labor, uterine contractions cause cervical dilation and effacement. Uterine ischemia (decreased blood flow and therefore local oxygen deficit) results from compression of the arteries supplying the myometrium during uterine contractions. Pain impulses during the first stage of labor are transmitted via the T-1 to T-12 spinal nerve segment and accessory lower thoracic and upper lumbar sympathetic nerves. These nerves originate in the uterine body and cervix (Blackburn, 2007). The pain from cervical changes, distention of the lower uterine segment, stretching of cervical tissue as it dilates, and pressure on adjacent structures and nerves during the first stage of labor is visceral pain. It is located over the lower portion of the abdomen. Referred pain occurs when the pain that originates in the uterus radiates to the abdominal wall, lumbosacral area of the back, iliac crests, gluteal area, thighs, and lower back (Blackburn, 2007; Zwelling et al., 2006). During the second stage of labor the woman has somatic pain, which is often described as intense, sharp, burning, and well localized. Pain results from stretching and distention of perineal tissues and the pelvic floor to allow passage of the fetus, from distention and traction on the peritoneum and uterocervical supports during contractions, and from lacerations of soft tissue (e.g., cervix, vagina, perineum). Other physical factors related to pain during second stage labor include fetal position, rapidity of fetal descent, maternal position, interval and duration of contractions, and fatigue (Zwelling et al., 2006). Pain impulses during the second stage of labor are transmitted via the pudendal nerve through S2 to S4 spinal nerve segments and the parasympathetic system (Blackburn, 2007). Pain experienced during the third stage of labor and the afterpains of the early postpartum period are uterine, similar to the pain experienced early in the first stage of labor. Areas of discomfort during labor are shown in Fig. 10-1. Pain during childbirth is unique to each woman. How she perceives or interprets that pain is influenced by a variety of physical, emotional, psychosocial, cultural, and environmental factors (Zwelling et al., 2006). A variety of physiologic factors can affect the intensity of pain that women experience during childbirth. Women with a history of dysmenorrhea may experience increased pain during childbirth as a result of higher prostaglandin levels. Back pain associated with menstruation also may increase the likelihood of contraction-related low back pain. Other physical factors include fatigue, the interval and duration of contractions, fetal position, rapidity of fetal descent, and maternal position (Zwelling et al., 2006). Endorphins are endogenous opioids secreted by the pituitary gland that act on the central and peripheral nervous systems to reduce pain. Beta-endorphin is the most potent of the endorphins. Endorphin levels increase during pregnancy and birth in humans. Endorphins are associated with feelings of euphoria and analgesia. Increased endorphin levels may increase the pain threshold and enable women in labor to tolerate acute pain (Blackburn, 2007). The obstetric population reflects the increasingly multicultural nature of U.S. society. As nurses care for women and families from a variety of cultural backgrounds, they must have knowledge and understanding of how culture mediates pain. Although all women expect to experience at least some pain and discomfort during childbirth, their culture and religious belief system determines how they will perceive, interpret, and respond to and manage the pain. For example, women with strong religious beliefs often accept pain as a necessary and inevitable part of bringing a new life into the world (Callister, Khalaf, Semenic, Kartchner, & Vehvilainen-Julkunen, 2003). An understanding of the beliefs, values, and practices of various cultures will narrow the cultural gap and help the nurse to assess the woman’s pain experience more accurately. The nurse can then provide appropriate culturally sensitive care by using pain-relief measures that preserve the woman’s sense of control and self-confidence (see Cultural Considerations box). Recognize that although a woman’s behavior in response to pain may vary according to her cultural background, it may not accurately reflect the intensity of the pain she is experiencing. Assess the woman for the physiologic effects of pain and listen to the words she uses to describe the sensory and affective qualities of her pain. Anxiety is commonly associated with increased pain during labor. Mild anxiety is considered normal for a woman during labor and birth. However, excessive anxiety and fear cause additional catecholamine secretion, which increases the stimuli to the brain from the pelvis because of decreased blood flow and increased muscle tension; this action, in turn, magnifies pain perception (Zwelling et al., 2006). Thus, as fear and anxiety heighten, muscle tension increases, the effectiveness of uterine contractions decreases, the experience of discomfort increases, and a cycle of increased fear and anxiety begins. Ultimately this cycle will slow the progress of labor. The woman’s confidence in her ability to cope with pain will be diminished, potentially resulting in reduced effectiveness of pain-relief measures being used. Sensory pain for nulliparous women is often greater than that for multiparous women during early labor (dilation less than 5 cm) because their reproductive tract structures are less supple. During the transition phase of the first stage of labor and during the second stage of labor, multiparous women may experience greater sensory pain than nulliparous women because their more supple tissue increases the speed of fetal descent and thereby intensifies pain. The firmer tissue of nulliparous women results in a slower, more gradual descent. Affective pain is usually increased for nulliparous women throughout the first stage of labor but decreases for both nulliparous and multiparous women during the second stage of labor (Lowe, 2002). Current evidence indicates that a woman’s satisfaction with her labor and birth experience is determined by how well her personal expectations of childbirth were met and the quality of support and interaction she receives from her caregivers. In addition, satisfaction is influenced by the degree to which the woman was able to stay in control of her labor and to participate in decision making regarding her labor, including the pain-relief measures to be used (Albers, 2007; Zwelling et al., 2006). The value of the continuous supportive presence of a person (e.g., doula, childbirth educator, family member, friend, nurse, partner) during labor has long been known. Women who have continuous support beginning early in labor are less likely to use pain medication or epidurals, more likely to have a spontaneous vaginal birth, and less likely to report dissatisfaction with their birth experience. No harmful effects from continuous labor support have been identified. To the contrary, good evidence exists that labor support improves important health outcomes. Interestingly, a more positive effect was achieved when the continuous support was provided by people who were not hospital staff members (Albers, 2007; Berghella, Baxter, & Chauhan, 2008; Hodnett, Gates, Hofmeyr, & Sakala, 2007). The quality of the environment can influence pain perception. Environment includes both the persons present (e.g., how they communicate, their philosophy of care, practice policies, and quality of support) and the physical space in which the labor occurs (Zwelling et al., 2006). Women usually prefer to be cared for by familiar caregivers in a comfortable, homelike setting. The environment should be safe and private, allowing a woman to feel free to be herself as she tries out different comfort measures. Stimuli that includes light, noise, and temperature should be adjusted according to the woman’s preferences. The environment should have space for movement, and equipment such as birth balls, comfortable chairs, tubs, and showers should be readily available to facilitate a variety of nonpharmacologic pain-relief measures. The familiarity of the environment can be enhanced by bringing items from home such as pillows, objects for a focal point, music, and DVDs. Many of the nonpharmacologic methods for relief of discomfort are taught in different types of prenatal preparation classes, or the woman or couple may have read various books and magazine articles on the subject in advance. Many of these methods require practice for best results (e.g., hypnosis, patterned breathing and controlled relaxation techniques, biofeedback), although the nurse may use some of them successfully without the woman or couple having prior knowledge (e.g., slow paced breathing, massage and touch, effleurage, counterpressure). Women should be encouraged to try a variety of methods and to seek alternatives, including pharmacologic methods, if the measure being used is no longer effective (Box 10-1). An English physician, Grantly Dick-Read, published two books in which he theorized that pain in childbirth is socially conditioned and caused by a fear-tension-pain syndrome. His first book, Natural Childbirth, was published in 1933. Dick-Read’s second book, Childbirth without Fear, was published in the United States in 1944. The work of Dick-Read became the foundation for organized programs of preparation for childbirth and teacher training throughout the United States, Canada, Great Britain, and South Africa. In 1960, persons prepared through such programs established the International Childbirth Education Association (ICEA). The Grantly Dick-Read method, known as Childbirth without Fear, initially recommended deep abdominal breathing during early first-stage contractions, shallow breathing for later first stage, and sustained pushing with breath holding (Dick-Read, 1987). Women were taught to relax different muscle groups through the entire body, consciously and progressively, until a high degree of skill at relaxation was achieved. Consequently, a woman was taught to relax completely between contractions and keep all muscles except the uterus relaxed during contractions. In 1960 the American Society for Psychoprophylaxis in Obstetrics (ASPO) was formed in New York and became a national organization to promote use of the Lamaze method and prepare teachers of the method. It continues to be an active organization, known since 1998 as Lamaze International and dedicated to advancing normal birth. Lamaze’s Institute of Normal Birth publishes reviews of research related to normal birth. In the official Lamaze Guide to Giving Birth with Confidence, the authors state that “Mothers do know how to give birth, simply. And doctors, hospitals and technology have not made normal birth safer” (Lothian & Devries, 2005). They further state that women need to rediscover birth as a natural part of life based on research that confirms that interfering in the normal birth process is harmful unless clear evidence exists that interference provides benefits. A third early advocate of prepared childbirth was the Denver obstetrician, Robert Bradley, who published Husband-Coached Childbirth in 1965. He advocated what he called true “natural” childbirth, without any form of anesthesia or analgesia and with a husband-coach and breathing techniques for labor. The American Academy of Husband-Coached Childbirth (AAHCC) was founded to make the Bradley method available and to prepare teachers (www.bradleybirth.com). This method of partner-coached childbirth used breath control, abdominal breathing, and general body relaxation. Working in harmony with the body was emphasized (Bradley, 1965). Bradley’s technique emphasized environmental variables such as darkness, solitude, and quiet to make childbirth a more natural experience. Women using the Bradley method may appear to be sleeping during labor because they are in such a deep state of mental relaxation. By reducing tension and stress, focusing and relaxation techniques allow a woman in labor to rest and to conserve energy for the task of giving birth. Attention-focusing and distraction techniques are forms of care that are effective to some degree in relieving labor pain (Albers, 2007). Some women bring a favorite object such as a photograph or stuffed animal to the labor room and focus their attention on this object during contractions. Others choose to fix their attention on some object in the labor room. As the contraction begins, they focus on their chosen object and perform a breathing technique to reduce their perception of pain. These techniques, coupled with feedback relaxation, help the woman work with her contractions rather than against them. The support person monitors this process, telling the woman when to begin the breathing techniques (Fig. 10-2). During childbirth preparation classes the coach can learn how to palpate a woman’s body to detect tense and contracted muscles. The woman then learns how to relax the tense muscle in response to the gentle stroking of the muscle by the coach (Fig. 10-3). In a common feedback mechanism the woman and her coach say the word “relax” at the onset of each contraction and throughout it as needed. With practice the coach can effectively use support, feedback, and touch to facilitate the woman’s relaxation and thereby reduce tension and stress and enhance the progress of labor (Humenick, Schrock, & Libresco, 2000). The nurse can assist the woman by providing a quiet environment and offering cues as needed. Various breathing techniques can be used for controlling pain during contractions (Box 10-2). The nurse needs to determine what, if any, techniques the laboring couple knows before giving them instruction. Simple patterns are more easily learned. Paced breathing is the technique most associated with prepared childbirth and includes slow-paced, modified-paced, and pant-blow breathing techniques. Each labor is different, and nursing support includes assisting couples to adapt breathing techniques to their individual labor experience. All patterns begin with a deep relaxing cleansing breath to “greet the contraction” and end with another deep breath exhaled to “gently blow the contraction away.” In general, slow-paced breathing is performed at approximately one half the woman’s normal breathing rate. The woman should take no fewer than three to four breaths per minute. Slow-paced breathing aids in relaxation and provides optimal oxygenation. As contractions increase in frequency and intensity the woman often needs to change to a more complex breathing technique, which is shallower and faster than the woman’s normal rate of breathing, but should not exceed twice her resting respiratory rate. This modified-paced breathing pattern allows the woman to be more focused and alert (Perinatal Education Associates, 2008 [www.birthsource.com]). The most difficult time to maintain control during contractions comes during the transition phase of the first stage of labor, when the cervix dilates from 8 cm to 10 cm. Even for the woman who has prepared for labor, concentration on breathing techniques is difficult to maintain. The pant-blow breathing technique is suggested for use during this phase. It is performed at the same rate as modified-paced breathing and consists of panting breaths combined with soft blowing breaths at regular intervals. The patterns may vary (i.e., pant, pant, pant, pant, blow or pant, pant, pant, blow) (Perinatal Education Associates, 2008). An undesirable side effect of this type of breathing is hyperventilation. The woman and her support person must be aware of and watch for symptoms of the resultant respiratory alkalosis: light-headedness, dizziness, tingling of the fingers, or circumoral numbness. Respiratory alkalosis may be eliminated by having the woman breathe into a paper bag held tightly around her mouth and nose, which enables her to rebreathe carbon dioxide and replace the bicarbonate ion. The woman also can breathe into her cupped hands if no bag is available. Maintaining a breathing rate that is no more than twice the normal rate will lessen chances of hyperventilation. The partner can help the woman maintain her breathing rate with visual, tactile, or auditory cues. As the fetal head reaches the pelvic floor the woman may feel the urge to push and may automatically begin to exert downward pressure by contracting her abdominal muscles. During second stage pushing the woman should find a breathing pattern that is relaxing and feels good for her and her baby. Any regular or rhythmic breathing that avoids prolonged breath holding during pushing should maintain a good oxygen flow to the fetus (Perinatal Education Associates, 2008). In addition to pain relief, hydrotherapy offers other benefits. If the woman is having “back labor” as the result of an occiput posterior or transverse position, hydrotherapy can enhance fetal rotation to the occiput anterior position as a result of increased buoyancy. Hydrotherapy may also encourage a greater use of the upright position and more movements that facilitate labor progress and coping (Stark, Rudell, & Haus, 2008). In addition, it promotes faster labor, less use of intramuscular and intravenous pain medications, less use of epidural anesthesia, fewer forceps- or vacuum-assisted births, fewer episiotomies, less perineal trauma, and increased satisfaction with the birth experience (Zwelling et al., 2006). When hydrotherapy is in use the fetal heart rate (FHR) is monitored by Doppler device, fetoscope, or wireless external monitor device (Fig. 10-4, C). Placement of internal electrodes is contraindicated for jet hydrotherapy. Several studies have investigated the risks of using hydrotherapy with ruptured membranes. Findings have shown no increases in chorioamnionitis, postpartum endometritis, neonatal infections, or antibiotic use. However, care must be taken to use tubs that can easily be thoroughly cleaned and a unit policy should be developed for cleaning the tubs (Tournaire & Theau-Yonneau, 2007; Zwelling et al., 2006). Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) involves the placing of two pairs of flat electrodes on either side of the woman’s thoracic and sacral spine (Fig. 10-5). These electrodes provide continuous low-intensity electrical impulses or stimuli from a battery-operated device. Women describe the resulting sensation as a tingling or buzzing. TENS is most useful for lower back pain during the early first stage of labor. Patients tend to rate the device as helpful, although its use does not decrease pain scores or the use of additional analgesics. Although TENS units do not change the degree of pain, apparently they somehow may make the pain less disturbing. No serious safety concerns associated with the use of TENS have been found (Hawkins, Goetzl, & Chestnut, 2007). Acupressure and acupuncture techniques can be used in pregnancy, in labor, and postpartum to relieve pain and other discomforts. Pressure, heat, or cold is applied to acupuncture points called tsubos. These points have an increased density of neuroreceptors and increased electrical conductivity. Acupressure is said to promote circulation of blood, the harmony of yin and yang and the secretion of neurotransmitters, thus maintaining normal body functions and enhancing well-being (Tournaire & Theau-Yonneau, 2007). Acupressure is best applied over the skin without using lubricants. Pressure is usually applied with the heel of the hand, fist, or pads of the thumbs and fingers (Fig. 10-6). Tennis balls or other devices also may be used to apply pressure. Pressure is applied with contractions initially and then continuously as labor progresses to the transition phase at the end of the first stage of labor (Tournaire & Theau-Yonneau). Synchronized breathing by the caregiver and the woman is suggested for greater effectiveness. Acupressure points are found on the neck, the shoulders, the wrists, the lower back, including sacral points, the hips, the area below the kneecaps, the ankles, the nails on the small toes, and the soles of the feet. Touch can be as simple as holding the woman’s hand, stroking her body, and embracing her. When using touch to communicate caring, reassurance, and concern, the woman’s preferences for touch (e.g., who can touch her, where they can touch her, and how they can touch her) and responses to touch should be determined. Women who perceive touch during labor as positive have less pain, anxiety, and need for pain medication (Tournaire & Theau-Yonneau, 2007). Touch also can involve very specialized techniques that require manipulation of the human energy field. Therapeutic touch (TT) uses the concept of energy fields within the body called prana. Prana are thought to be deficient in some people who are in pain. TT uses laying-on of hands by a specially trained person to redirect energy fields associated with pain (Aghabati, Mohammadi, & Pour Esmaiel, 2008). Research has demonstrated the effectiveness of TT to enhance relaxation, reduce anxiety, and relieve pain (Aghabati et al.); however, little is known about the use or effectiveness of TT for relieving labor pain.

Management of Discomfort

Web Resources

![]()

Discomfort During Labor and Birth

Neurologic Origins

Factors Influencing Pain Response

Physiologic factors

Culture

Anxiety

Previous experience

Comfort

Support.

![]()

Environment.

Nonpharmacologic Management af Discomfort

Childbirth Preparation Methods

Relaxing and Breathing Techniques

Focusing and relaxation

Breathing techniques

Music

![]() Music, recorded or live, can enhance relaxation and lift spirits during labor, thereby reducing the woman’s level of stress, anxiety, and perception of pain. It can be used to promote relaxation in early labor and to stimulate movement as labor progresses (Zwelling et al., 2006). Women should be encouraged to prepare their musical preferences in advance and bring a compact disk player or iPod to the hospital or birthing center. Use of a headset or earphones may increase the effectiveness of the music because other sounds will be shut out. Live music provided at the bedside by a support person may also be very helpful in transmitting energy that decreases tension and elevates mood. Although promising, evidence at the present time is insufficient to support the effectiveness of music as a method of pain relief during labor. Further research is recommended (Smith, Collins, Cyna, & Crowther, 2006).

Music, recorded or live, can enhance relaxation and lift spirits during labor, thereby reducing the woman’s level of stress, anxiety, and perception of pain. It can be used to promote relaxation in early labor and to stimulate movement as labor progresses (Zwelling et al., 2006). Women should be encouraged to prepare their musical preferences in advance and bring a compact disk player or iPod to the hospital or birthing center. Use of a headset or earphones may increase the effectiveness of the music because other sounds will be shut out. Live music provided at the bedside by a support person may also be very helpful in transmitting energy that decreases tension and elevates mood. Although promising, evidence at the present time is insufficient to support the effectiveness of music as a method of pain relief during labor. Further research is recommended (Smith, Collins, Cyna, & Crowther, 2006).

Water Therapy (Hydrotherapy)

![]() Bathing, showering, and jet hydrotherapy (whirlpool baths) with warm water (e.g., at or below body temperature) are nonpharmacologic measures that can be used to promote comfort and relaxation during labor (Fig. 10-4). The warm water stimulates the release of endorphins, relaxes fibers to close the gate on pain, and promotes better circulation and oxygenation. Most women find immersion in water to be soothing, relaxing, and comforting. While immersed, they may find it easier to let go and allow labor to take its course (Gilbert, 2007). Immersion in water has been reported to be effective in relieving pain by women who used this technique during labor (Albers, 2007).

Bathing, showering, and jet hydrotherapy (whirlpool baths) with warm water (e.g., at or below body temperature) are nonpharmacologic measures that can be used to promote comfort and relaxation during labor (Fig. 10-4). The warm water stimulates the release of endorphins, relaxes fibers to close the gate on pain, and promotes better circulation and oxygenation. Most women find immersion in water to be soothing, relaxing, and comforting. While immersed, they may find it easier to let go and allow labor to take its course (Gilbert, 2007). Immersion in water has been reported to be effective in relieving pain by women who used this technique during labor (Albers, 2007).![]()

Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation

Acupressure and Acupuncture

![]() Acupuncture is the insertion of fine needles into specific areas of the body to restore the flow of qi (energy) and to decrease pain, which is thought to be obstructing the flow of energy. Acupuncture may work by altering the level of chemical neurotransmitters in the body or by releasing endorphins as a result of activation of the hypothalamus. It should be performed by a trained certified therapist. Current evidence indicates that acupuncture may be beneficial for relief of labor pain; however, further study is indicated (Hawkins et al., 2007; Smith et al., 2006; Tournaire & Theau-Yonneau, 2007).

Acupuncture is the insertion of fine needles into specific areas of the body to restore the flow of qi (energy) and to decrease pain, which is thought to be obstructing the flow of energy. Acupuncture may work by altering the level of chemical neurotransmitters in the body or by releasing endorphins as a result of activation of the hypothalamus. It should be performed by a trained certified therapist. Current evidence indicates that acupuncture may be beneficial for relief of labor pain; however, further study is indicated (Hawkins et al., 2007; Smith et al., 2006; Tournaire & Theau-Yonneau, 2007).

Touch and Massage

![]() Touch and massage have been an integral part of the traditional care process for women in labor. A variety of massage techniques have been shown to be safe and effective during labor (Gilbert, 2007; Zwelling et al., 2006).

Touch and massage have been an integral part of the traditional care process for women in labor. A variety of massage techniques have been shown to be safe and effective during labor (Gilbert, 2007; Zwelling et al., 2006).

![]()

Hypnosis

![]() Hypnosis is a form of deep relaxation, similar to daydreaming or meditation. While under hypnosis, women are in a state of focused concentration, and the subconscious mind can be more easily accessed (Gilbert, 2007). Hypnosis techniques used for labor and birth place an emphasis on enhancing relaxation and diminishing fear, anxiety, and perception of pain. Current evidence suggests that hypnosis seems to reduce fear, tension, and pain during labor and to raise the pain threshold. Women using this technique report a greater sense of control over painful contractions. Because it reduces the need for pain medication, hypnosis can be helpful when used with other interventions during labor. A few negative effects of hypnosis have been reported, including mild dizziness, nausea, and headache. These effects seem to be associated with failure to dehypnotize the patient properly (Tournaire & Theau-Yonneau, 2007).

Hypnosis is a form of deep relaxation, similar to daydreaming or meditation. While under hypnosis, women are in a state of focused concentration, and the subconscious mind can be more easily accessed (Gilbert, 2007). Hypnosis techniques used for labor and birth place an emphasis on enhancing relaxation and diminishing fear, anxiety, and perception of pain. Current evidence suggests that hypnosis seems to reduce fear, tension, and pain during labor and to raise the pain threshold. Women using this technique report a greater sense of control over painful contractions. Because it reduces the need for pain medication, hypnosis can be helpful when used with other interventions during labor. A few negative effects of hypnosis have been reported, including mild dizziness, nausea, and headache. These effects seem to be associated with failure to dehypnotize the patient properly (Tournaire & Theau-Yonneau, 2007).

Biofeedback

![]() Biofeedback may provide another relaxation technique that can be used for labor. Biofeedback is based on the theory that if a person can recognize physical signals, certain internal physiologic events can be changed (i.e., whatever signs the woman has that are associated with her pain). For biofeedback to be effective the woman must be educated during the prenatal period to become aware of her body and its responses and how to relax. The woman must learn how to use thinking and mental processes (e.g., focusing) to control body responses and functions. Informational biofeedback helps couples develop awareness of their bodies and use strategies to change their responses to stress. If the woman responds to pain during a contraction with tightening of muscles, frowning, moaning, and breath holding, her partner uses verbal and touch feedback to help her relax. Formal biofeedback, which uses machines to detect skin temperature, blood flow, or muscle tension, can also prepare women to intensify their relaxation responses. Biofeedback-assisted relaxation techniques are not always successful in reducing labor pain. Using these techniques effectively requires the strong support of caregivers (Tournaire & Theau-Yonneau, 2007).

Biofeedback may provide another relaxation technique that can be used for labor. Biofeedback is based on the theory that if a person can recognize physical signals, certain internal physiologic events can be changed (i.e., whatever signs the woman has that are associated with her pain). For biofeedback to be effective the woman must be educated during the prenatal period to become aware of her body and its responses and how to relax. The woman must learn how to use thinking and mental processes (e.g., focusing) to control body responses and functions. Informational biofeedback helps couples develop awareness of their bodies and use strategies to change their responses to stress. If the woman responds to pain during a contraction with tightening of muscles, frowning, moaning, and breath holding, her partner uses verbal and touch feedback to help her relax. Formal biofeedback, which uses machines to detect skin temperature, blood flow, or muscle tension, can also prepare women to intensify their relaxation responses. Biofeedback-assisted relaxation techniques are not always successful in reducing labor pain. Using these techniques effectively requires the strong support of caregivers (Tournaire & Theau-Yonneau, 2007).![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Management of Discomfort

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access