Maintaining Fluid Balance and Meeting Nutrition Needs

Objectives

1. Identify the various types of nutrients.

2. Identify the components of a healthy diet for older adults.

3. Describe age-related changes in nutritional and fluid requirements.

4. Identify age-related changes that affect nutrition, digestion, and hydration.

5. Describe methods of assessing the nutritional status and practices of older adults.

6. Identify the older adults who are most at risk for problems related to nutrition and hydration.

7. Identify selected nursing diagnoses related to nutritional or metabolic problems.

8. Identify interventions that will help older persons meet their nutrition and hydration needs.

Key Terms

anemia (ă-NĒ-mē-ă) (p. 107)

basal metabolic rate (BĀ-săl mĕt-ă-BŎL- k rāt) (p. 103)

k rāt) (p. 103)

blood urea nitrogen (blŭd ū-RĒ-ă ŇI-trō-jĕn) (p. 113)

calories (KĂL-ŏ-rēs) (p. 102)

carbohydrates (kăr-bō- I-drāts) (p. 104)

I-drāts) (p. 104)

creatinine (krē-ĂT- -nēn) (p. 113)

-nēn) (p. 113)

edema (ĕ-DĒ-mă) (p. 121)

electrolyte (ē-LĔK-trō- lt) (p. 113)

lt) (p. 113)

hematocrit (hē-MĂT-ŏ-kr t) (p. 113)

t) (p. 113)

hemoglobin (HĒ-mō-glō-b n) (p. 113)

n) (p. 113)

interstitial ( n-tĕr-S

n-tĕr-S ISH-ăl) (p. 121)

ISH-ăl) (p. 121)

intracellular ( n-tră-SĔL-ū-lăr) (p. 121)

n-tră-SĔL-ū-lăr) (p. 121)

intravascular ( n-tră-VĂS-cū-lăr) (p. 121)

n-tră-VĂS-cū-lăr) (p. 121)

malnutrition (măl-nū-T ISH-ŭn) (p. 110)

ISH-ŭn) (p. 110)

minerals ( IN-ĕr-ălz) (p. 108)

IN-ĕr-ălz) (p. 108)

nasogastric (nā-zō-GĂS-tr k) (p. 120)

k) (p. 120)

proteins (PRŌ-tēnz) (p. 104)

supplement (SŬP-lĕ-mĕnt) (p. 120)

trace element (p. 109)

vitamins ( I-tă-m

I-tă-m nz) (p. 106)

nz) (p. 106)

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Wold/geriatric

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Wold/geriatric

Nutrition plays an important role in health maintenance, rehabilitation, and prevention and control of disease. When dealing with nutritional issues, nurses who work with older adults must consider the following: (1) the basic components of a well-balanced diet for older adults; (2) how the normal physiologic changes of aging change nutritional needs; (3) how the normal physiologic changes of aging may interfere with the purchase, preparation, and consumption of nutrients; and (4) how cognitive, psychosocial, and pathologic changes commonly seen in aging impact the aging individual’s nutritional status.

Nutrition and aging

Nutritional needs do not remain static throughout life. As with other needs, the nutritional needs of older adults are not exactly the same as those of younger individuals. An understanding of the nutritional needs of older adults is essential to providing good nursing care. To assess nutritional adequacy and select interventions that promote good nutrition, nurses must be knowledgeable about basic nutrition and diet therapy. Good nutrition practices play a vital role in health maintenance and health promotion. Good eating habits throughout life promote physical wellness and mental well-being. Inadequate nutrition and fluid intake can result in serious problems such as malnutrition and dehydration. Poor nutrition practices can contribute to the development of osteoporosis and skin ulcers and can complicate existing conditions such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus.

Caloric Intake

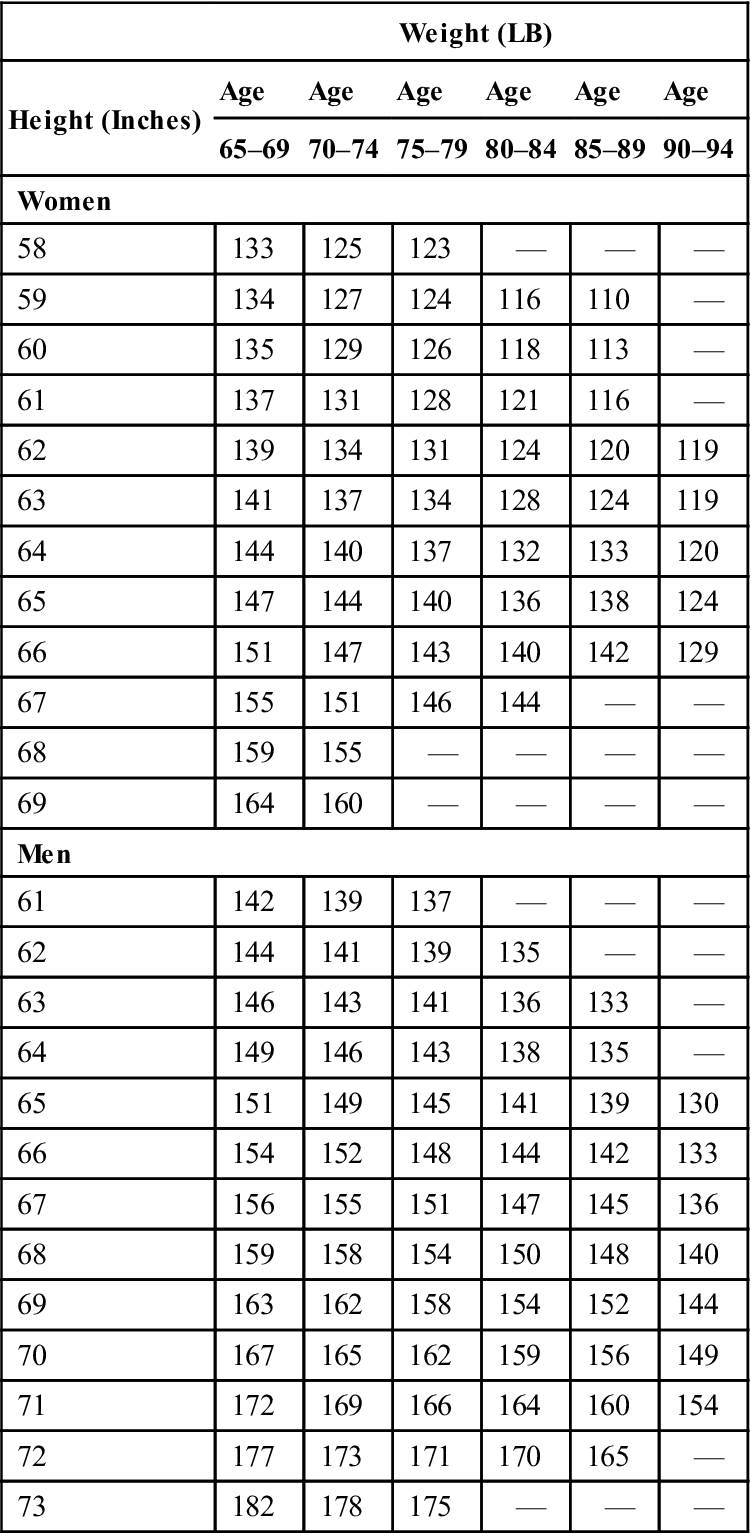

Calories are units of heat that are used to measure the available energy in consumed food. Because people’s energy requirements differ widely, the number of calories they require also differs significantly. Many factors influence how many calories will be used by a person: activity patterns, gender, body size, age, body temperature, emotional status, and the temperature of the climate in which the person lives. Both acute and chronic illnesses also have an impact on caloric needs. In general, when a person’s caloric intake is in balance with the energy needs of the body, his or her weight remains constant. When caloric intake exceeds energy needs, the excess is converted into adipose (fat) tissue for storage, and the individual gains weight. When caloric intake is less than the energy needs, the person loses weight (Table 6-1).

Table 6-1

Average Weight of Older Adults Per Height

| Weight (LB) | ||||||

| Height (Inches) | Age | Age | Age | Age | Age | Age |

| 65–69 | 70–74 | 75–79 | 80–84 | 85–89 | 90–94 | |

| Women | ||||||

| 58 | 133 | 125 | 123 | — | — | — |

| 59 | 134 | 127 | 124 | 116 | 110 | — |

| 60 | 135 | 129 | 126 | 118 | 113 | — |

| 61 | 137 | 131 | 128 | 121 | 116 | — |

| 62 | 139 | 134 | 131 | 124 | 120 | 119 |

| 63 | 141 | 137 | 134 | 128 | 124 | 119 |

| 64 | 144 | 140 | 137 | 132 | 133 | 120 |

| 65 | 147 | 144 | 140 | 136 | 138 | 124 |

| 66 | 151 | 147 | 143 | 140 | 142 | 129 |

| 67 | 155 | 151 | 146 | 144 | — | — |

| 68 | 159 | 155 | — | — | — | — |

| 69 | 164 | 160 | — | — | — | — |

| Men | ||||||

| 61 | 142 | 139 | 137 | — | — | — |

| 62 | 144 | 141 | 139 | 135 | — | — |

| 63 | 146 | 143 | 141 | 136 | 133 | — |

| 64 | 149 | 146 | 143 | 138 | 135 | — |

| 65 | 151 | 149 | 145 | 141 | 139 | 130 |

| 66 | 154 | 152 | 148 | 144 | 142 | 133 |

| 67 | 156 | 155 | 151 | 147 | 145 | 136 |

| 68 | 159 | 158 | 154 | 150 | 148 | 140 |

| 69 | 163 | 162 | 158 | 154 | 152 | 144 |

| 70 | 167 | 165 | 162 | 159 | 156 | 149 |

| 71 | 172 | 169 | 166 | 164 | 160 | 154 |

| 72 | 177 | 173 | 171 | 170 | 165 | — |

| 73 | 182 | 178 | 175 | — | — | — |

Various nutrients provide different amounts of calories. Fats, which can come from either plant sources (e.g., oleomargarine) or animal sources (e.g., butter), yield 9 calories/g. Proteins and carbohydrates yield 4 calories/g. Vitamins, minerals, and water yield no calories. Alcohol yields 7 calories/g without contributing any nutritional value.

Studies have shown that caloric needs in healthy individuals decrease at a rate of approximately 5% for each decade between ages 55 and 75 years and 7% percent for each decade after age 75. The body’s muscle and lean tissue masses decrease with aging, and adipose tissue increases. As the proportion of muscle and fat changes, the basal metabolic rate (the rate at which the body uses calories) decreases. The normal decrease in physical activity commonly seen with aging further slows the rate at which the body burns calories. Healthy individuals who maintain an active lifestyle that includes exercise may see little need to change their caloric intake. Inactive individuals may need to restrict caloric intake significantly. The lowest recommended daily intake to adequately meet nutritional needs is 1200 calories.

When determining the adequacy of caloric intake, disease processes must be considered. Diseases that result in restricted mobility and physical activity (e.g., arthritis and stroke) are likely to decrease caloric needs. Other disease processes (e.g., infections and various forms of cancer) actually increase the body’s caloric requirements. Individuals suffering from diabetes mellitus require special diets, which are prescribed by a physician. Diet plays an important role in the medical management of diabetes and is used to control and treat the disease. The diabetic diet normally includes calorie restrictions and is specially balanced with regard to the percentage of fats, proteins, and carbohydrates.

Nutrients

Although caloric needs often decrease with age, the need to include all of the various nutrients does not. Therefore, foods high in nutritional value and relatively low in calories must be selected to maximize the amount of nutrients the body receives while reducing the number of calories.

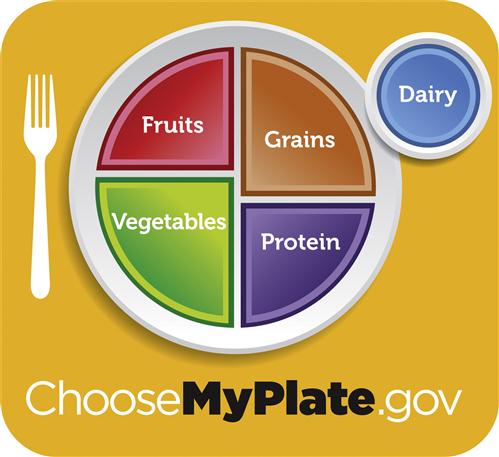

Vital nutrients needed by all people include carbohydrates, protein, fats, vitamins, minerals, and fluids. Because many foods contain a combination of these nutrients, various methods of determining nutritional balance have been developed. One way to measure the adequacy of a person’s diet and nutritional intake is determined by comparing his or her intake to accepted standards. The most common standard for determining the balance of a diet plan is the food pyramid (Figure 6-1). This pyramid has been revised several times through the years to best reflect our understanding of nutritional needs. The current form, MyPlate, was designed by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) in 2011. The plate is divided into color-coded food groups, including vegetables, fruits, grains, and protein, with dairy on the side. Regardless of the total amount of food consumed, the proportion of food from each group should remain in balance.

The plan is intended to be simple so that people of all ages and educational background are able to use it. More than just a diet, MyPlate offers a health plan that encourages users to adopt healthier eating habits and increase physical activity. General recommendations from the USDA (2011) for the general population include:

• Enjoying food but eating less of it

• Increasing intake of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains

• Choosing low-fat or fat-free dairy products

• Drinking water instead of sugary beverages

Additional tips and resources, including recipes and interactive tools are available at www.ChooseMyPlate.gov.

A modified food guide for Older Adults is available in Appendix C.

Other more detailed standards for measuring the nutritional adequacy of a diet are found in the Dietary Reference Intakes, which include the recommended dietary allowances (RDAs) and the adequate intakes (AIs) (see Appendix C). These references specify the recommendations for the following:

• Calories

• Macronutrients such as protein, carbohydrates, and fats

• Fiber

• Elemental minerals, including iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, selenium, vanadium, zinc, etc.

• Vitamins

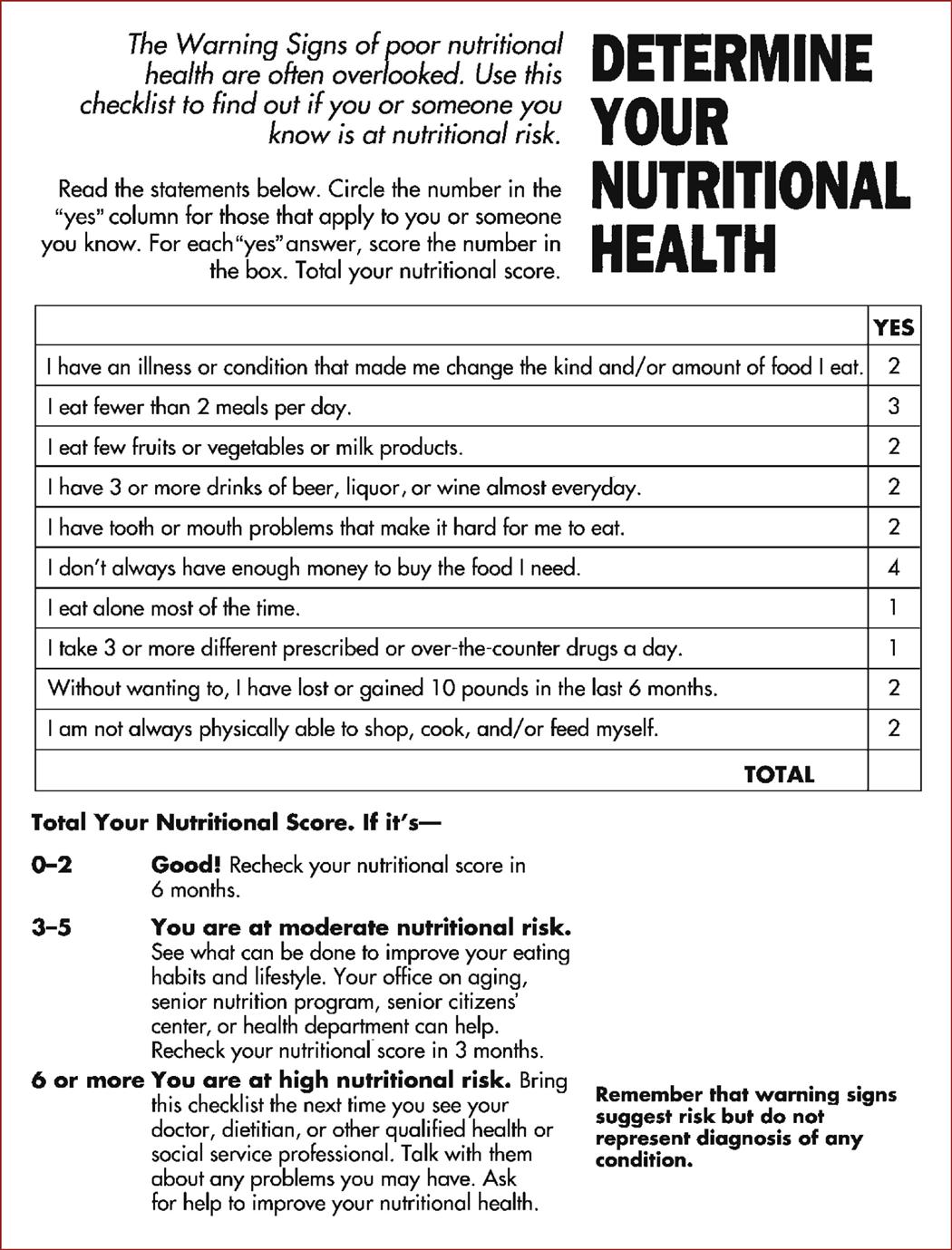

Dietary reference intakes are a more complex way of analyzing dietary intake. Use of these standards requires careful weighing and measurement of portions and use of nutritional references or complete nutrition labels that list all of the ingredients in detail. Some older adults may consult these recommendations when selecting vitamins or other nutrients. Nutritional labels are commonly used by physicians, nurses, or dietitians when developing a specific therapeutic diet plan. A more general checklist that older adults can use to determine their nutritional health is shown in Figure 6-2.

Carbohydrates

Carbohydrates include the familiar sugars and starches that compose approximately half of the standard American diet. A ready source of energy for the body, carbohydrates are usually divided into two categories: simple and complex. Simple carbohydrates are used most readily by the body because their bonds are easily broken. Table sugar, honey, syrup, and candy are examples of simple carbohydrates. Complex carbohydrates must be broken down into simple sugars before they can be used by the body. This breakdown requires time and energy. Foods such as vegetables, whole grains, and fruits contain complex carbohydrates. Foods that contain complex carbohydrates usually also contain other nutrients (e.g., minerals and vitamins), making them more nutritious than foods containing simple carbohydrates only. The American Heart Association recommends that 55% to 60% of calories should come from carbohydrates, with an emphasis on complex carbohydrates. This recommendation appears to be appropriate for the aging population.

In addition to providing essential nutrients, complex carbohydrates usually contain significant amounts of soluble fiber, a substance humans cannot digest, which forms bulk and aids bowel elimination. Fiber is recommended as helpful in preventing constipation, diverticulosis, and diverticulitis. A diet high in complex carbohydrates is recommended as part of the control of many disease processes. The soluble fiber in complex carbohydrates has been shown to reduce blood cholesterol levels, which is helpful for individuals who are at risk for coronary artery disease. Complex carbohydrates also play an important role in the control of diabetes, because they effectively meet energy needs without causing rapid increases in blood glucose levels the way simple sugars do.

Proteins

Proteins are composed of amino acids, which are essential for tissue repair and healing. The need for protein remains constant or may increase slightly with aging to compensate for the loss of lean body tissue (Box 6-1). The RDA of protein for women older than 50 years of age is 50 g/day; for men older than age 50 years, the RDA is 65 g/day. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey reveal that 10% to 25% of women older than age 55 consume less than half of the recommended daily amount of protein. Protein consumption in older adults can be affected by many factors, including the ability to procure and prepare food, the cost of foods containing protein, and even the ability to chew common high-protein foods.

Tissue replacement and repair continue throughout life. Any condition in which tissue integrity is altered (e.g., surgery and pressure ulcers) increases the amount of protein needed to aid in tissue repair. Red meats, poultry, fish, eggs, and dairy products are good sources of complete proteins, which contain all of the amino acids necessary for making and repairing tissues. Plant foods such as legumes (peas and beans), nuts, and cereals (whole grains and rice) contain smaller amounts of incomplete proteins, which do not individually contain all of the necessary amino acids. Incomplete proteins must be combined carefully to meet protein needs.

Some foods that are high in protein such as steak, ham, organ meats, egg yolks, hard cheese, and whole milk also contain large amounts of fats. Excessive consumption of proteins with a high fat content can contribute to elevated blood levels of cholesterol and triglycerides, which, in turn, contribute to plaque formation and atherosclerotic changes in the blood vessels. Atherosclerosis often results in hypertension and heart disease. For this reason, many physicians and dietitians recommend that high-fat protein foods be restricted. A person who is on a fat-restricted diet should consume low-fat proteins such as fish and lean poultry, as well as protein from plant sources such as peas and beans.

Fats

It is recommended that fats be limited to approximately 25% to 30% of the total daily caloric intake. This recommendation does not change with aging. A certain amount of fat is necessary and desirable in the diet to aid in the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins and to provide adequate amounts of essential fatty acids. Fat is desirable because it adds flavor to food and provides a sense of fullness with a meal. Foods with no fat would be unappealing, poor tasting, and not very satisfying.

When considering fat intake in the diet, it is important to watch the type of fats ingested. The body incorporates fats into substances called lipoproteins, which contain cholesterol and proteins. There are three important types of lipoproteins: high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), and very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL). LDL is primarily composed of cholesterol and is believed to contribute to blood vessel disease. VLDL is primarily composed of triglycerides and may contribute to vessel disease but not as significantly as does LDL. HDL, the so-called healthy fat, is primarily composed of protein that appears to protect against blood vessel disease.

Some individuals who have been eating high-cholesterol foods for their entire lives may be reluctant to change their eating habits as they age. They may find it difficult or unpleasant to shop for and prepare foods in new ways. Others can successfully alter their dietary intake to avoid foods high in these substances.

Vitamins

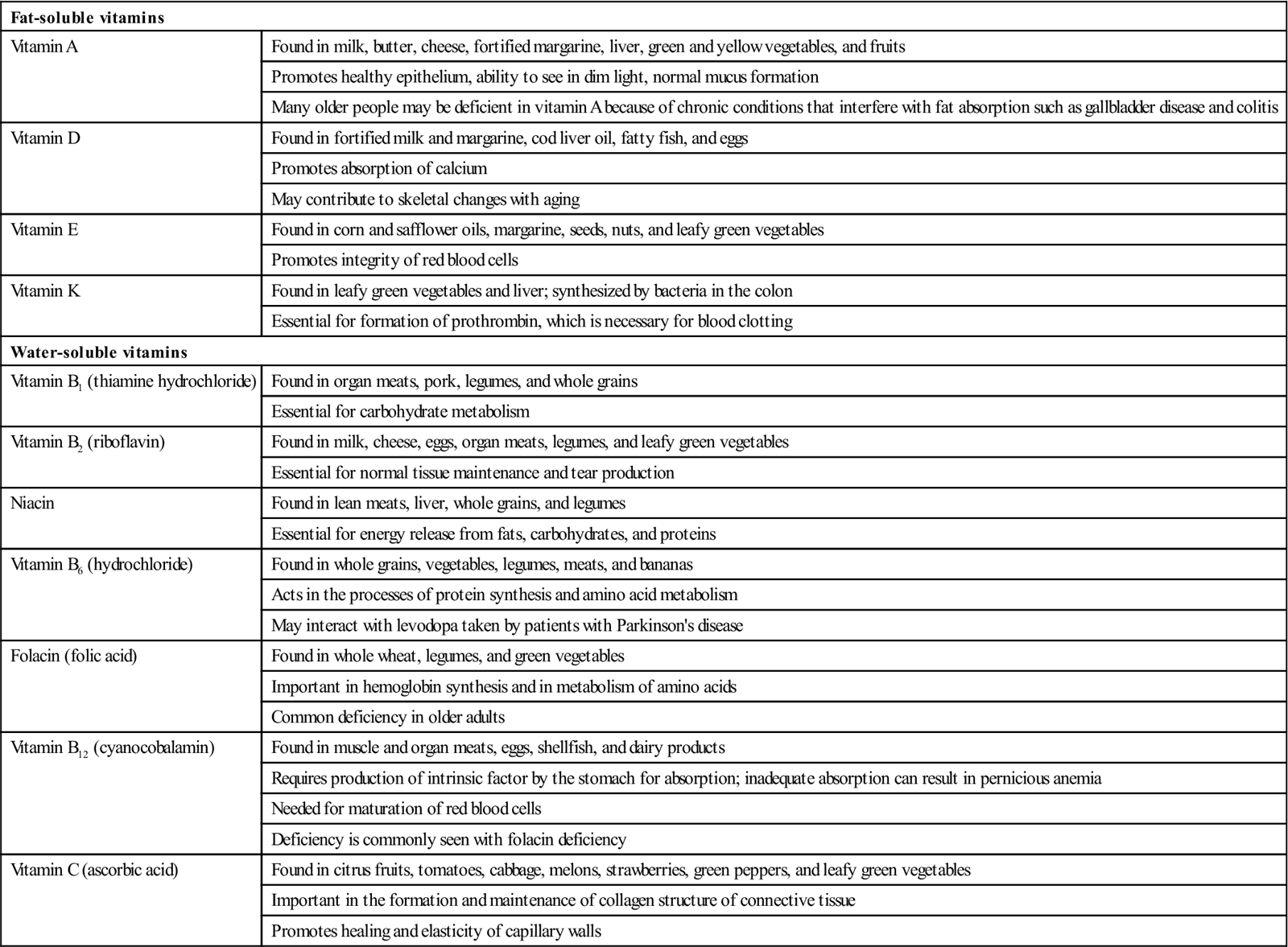

Vitamins are organic compounds found naturally in foods. They can also be produced synthetically. Vitamins are needed for a variety of metabolic and physiologic processes. Vitamins are classified as fat-soluble or water-soluble. The fat-soluble vitamins include vitamins A, D, E, and K. The B-complex vitamins and vitamin C are water-soluble (Table 6-2).

Table 6-2

| Fat-soluble vitamins | |

| Vitamin A | Found in milk, butter, cheese, fortified margarine, liver, green and yellow vegetables, and fruits |

| Promotes healthy epithelium, ability to see in dim light, normal mucus formation | |

| Many older people may be deficient in vitamin A because of chronic conditions that interfere with fat absorption such as gallbladder disease and colitis | |

| Vitamin D | Found in fortified milk and margarine, cod liver oil, fatty fish, and eggs |

| Promotes absorption of calcium | |

| May contribute to skeletal changes with aging | |

| Vitamin E | Found in corn and safflower oils, margarine, seeds, nuts, and leafy green vegetables |

| Promotes integrity of red blood cells | |

| Vitamin K | Found in leafy green vegetables and liver; synthesized by bacteria in the colon |

| Essential for formation of prothrombin, which is necessary for blood clotting | |

| Water-soluble vitamins | |

| Vitamin B1 (thiamine hydrochloride) | Found in organ meats, pork, legumes, and whole grains |

| Essential for carbohydrate metabolism | |

| Vitamin B2 (riboflavin) | Found in milk, cheese, eggs, organ meats, legumes, and leafy green vegetables |

| Essential for normal tissue maintenance and tear production | |

| Niacin | Found in lean meats, liver, whole grains, and legumes |

| Essential for energy release from fats, carbohydrates, and proteins | |

| Vitamin B6 (hydrochloride) | Found in whole grains, vegetables, legumes, meats, and bananas |

| Acts in the processes of protein synthesis and amino acid metabolism | |

| May interact with levodopa taken by patients with Parkinson’s disease | |

| Folacin (folic acid) | Found in whole wheat, legumes, and green vegetables |

| Important in hemoglobin synthesis and in metabolism of amino acids | |

| Common deficiency in older adults | |

| Vitamin B12 (cyanocobalamin) | Found in muscle and organ meats, eggs, shellfish, and dairy products |

| Requires production of intrinsic factor by the stomach for absorption; inadequate absorption can result in pernicious anemia | |

| Needed for maturation of red blood cells | |

| Deficiency is commonly seen with folacin deficiency | |

| Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) | Found in citrus fruits, tomatoes, cabbage, melons, strawberries, green peppers, and leafy green vegetables |

| Important in the formation and maintenance of collagen structure of connective tissue | |

| Promotes healing and elasticity of capillary walls | |

The benefits of vitamins for older adults are being closely examined. Some researchers who subscribe to the free radical theory of aging are studying the effects of the so-called antioxidant vitamins. It is theorized that antioxidant vitamins can block or neutralize free radicals and prevent cell damage, thereby slowing the effects of aging and preventing a number of diseases such as cancer and heart disease. Although research into this area is promising, many experts are not yet convinced of the effectiveness of antioxidant vitamins or satisfied that we have an adequate understanding of their method of action, therapeutic dosage, and long-term effects. Vitamins A, C, and E are considered antioxidants.

Vitamin deficiencies have been connected to a variety of problems experienced by older adults, including the following:

• Inadequate intake of vitamin A may contribute to poor wound healing, dry skin, and night blindness.

• Vitamin K deficiency has recently been correlated to an increased risk of fractures.

Older adults who consume well-balanced diets may not require supplemental vitamins. Those with increased risk factors such as gastrointestinal (GI) problems or inadequate nutritional intake may benefit from selected vitamin supplements. Supplements should be used with caution and under the direction of a physician or dietitian. Excess amounts of the water-soluble vitamins are quickly eliminated from the body and pose few risks. Excess amounts of the fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K) are retained in fatty tissue or stored in the liver. Overconsumption of these vitamins can lead to toxic symptoms and even permanent liver damage.

Minerals

Minerals are inorganic chemical elements that are required in many of the body’s functions. Minerals make up a small proportion of total body weight, yet a slight mineral imbalance can have serious effects.

Calcium, the most abundant mineral in the body, is necessary for bone and tooth formation, nerve impulse transmission and conduction, muscle contraction (including cardiac function), and blood clotting. The main dietary sources of calcium are milk and dairy products. Calcium is normally retained in bone, with only a small amount (1%) found in the tissues and blood. With aging and with immobility, the bones tend to lose calcium, resulting in osteoporosis. In certain disease states, abnormal amounts of calcium leave the bone, enter the bloodstream, and cause hypercalcemia, which is an elevated level of calcium in the blood. Hypercalcemia is seen with hyperparathyroidism, disuse atrophy, metastatic bone tumors, and vitamin D excess.

Individuals experiencing hypercalcemia may manifest symptoms, including confusion, abdominal pain, muscle pain, weakness, and anorexia. These symptoms may be easily missed in older individuals because they are vague and common to many other conditions. Extremely high levels of calcium in the blood can result in shock, kidney failure, and even death. When the kidneys attempt to rid the body of excess calcium, hypercalciuria (increased calcium in the urine) results, and the risk for renal calculi (kidney stone) formation is increased.

Adequate calcium intake is important throughout life, but it is particularly important for those at risk for developing osteoporosis, especially postmenopausal women. Calcium may arrest the progress of osteoporosis. Vitamin D aids in the absorption of calcium. For this reason, vitamin D is added to milk products and fortified margarine.

Phosphorus is needed for normal bone and tooth formation, activation of some B vitamins, normal neuromuscular functioning, metabolism of carbohydrates, regulation of acid-base balance, and other physiologic processes. Inadequate nutritional intake of phosphorus can result in weight loss or anemia. The typical dietary sources of phosphorous compounds are dairy products, meat, egg yolks, peas, beans, nuts, and whole grains. Because of its wide availability, meeting the dietary requirements of this mineral normally is not a problem unless the individual is on a highly restricted diet.

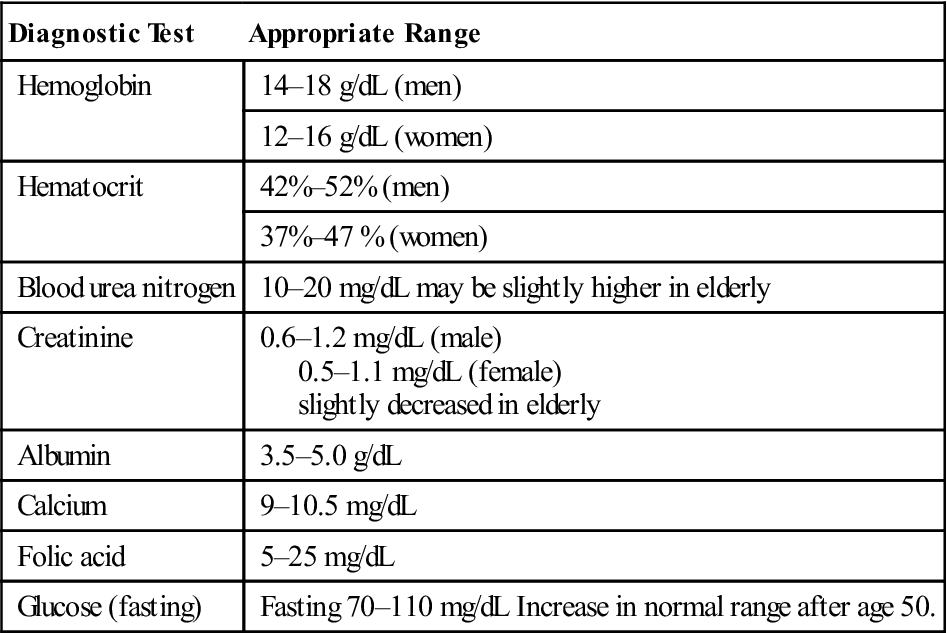

Iron is found in the center of the heme portion of hemoglobin. Hemoglobin in the red blood cells transports oxygen to and removes carbon dioxide from the cells. Without adequate amounts of iron, the body cannot produce enough hemoglobin. When hemoglobin levels fall below the normal range, anemia results. Individuals suffering from anemia may manifest many symptoms, depending on the severity of the condition: fatigue, exertional dyspnea, tachycardia, palpitations, headache, insomnia, vertigo, pallor (particularly of the mucous membranes), and cool extremities. The normal changes of aging or other disease processes may resemble these symptoms and prevent recognition of anemia. Laboratory tests for hemoglobin levels are required to determine whether anemia is present (Table 6-3). Two forms of nutritional anemia are commonly seen in older adults: iron-deficiency anemia and pernicious anemia.

Table 6-3

Laboratory Values Used to Assess Nutritional Adequacy in Older Adults

| Diagnostic Test | Appropriate Range |

| Hemoglobin | 14–18 g/dL (men) |

| 12–16 g/dL (women) | |

| Hematocrit | 42%–52% (men) |

| 37%–47 % (women) | |

| Blood urea nitrogen | 10–20 mg/dL may be slightly higher in elderly |

| Creatinine | 0.6–1.2 mg/dL (male) 0.5–1.1 mg/dL (female) slightly decreased in elderly |

| Albumin | 3.5–5.0 g/dL |

| Calcium | 9–10.5 mg/dL |

| Folic acid | 5–25 mg/dL |

| Glucose (fasting) | Fasting 70–110 mg/dL Increase in normal range after age 50. |

Data from Pagana KD and Pagana TJ: Mosby’s Manual of Diagnostic and Laboratory Tests, ed 4, St Louis, 2010, Mosby.

Iron-deficiency anemia results from inadequate intake of dietary iron. Rich sources of dietary iron include red meat, particularly organ meats such as liver; shellfish; egg yolks; leafy green vegetables; and dried fruits. Red meat is expensive and, unless properly prepared, can be difficult for older adults to chew. Many people do not like the taste of liver and organ meats and refuse to eat them. In addition, organ meats and egg yolks are high in cholesterol, which is often restricted from the diet. This can make meal planning difficult. In addition to increased nutritional intake of iron rich foods, folic acid and iron supplements are commonly prescribed.

It should be remembered that a concentrated iron formulation (liquid or solid) administered orally can irritate the GI tract. To reduce GI irritation, iron supplements should be taken during or after meals. Iron solutions can stain the teeth, so a straw should be used with liquid iron preparations. If iron is given by injection, it is important to use the Z-track method for deep intramuscular administration. Foods rich in vitamin C should be given in conjunction with iron to enhance its absorption. Patients should be told that iron will probably turn the stool a dark green or black color, and nurses should keep this in mind when assessing the stool of individuals receiving iron supplements. Concentrated iron supplements can also cause diarrhea.

Pernicious anemia is caused by a deficiency in intrinsic factor secreted by the stomach. Without this factor, vitamin B12, which is required for red blood cell maturation in the bone marrow, is not absorbed. In addition, there are fewer white blood cells and there may be cellular changes in the existing cells. Individuals suffering from pernicious anemia may manifest weakness, numbness, or tingling in the extremities; anorexia; or weight loss. Treatment typically consists of cyanocobalamin injections and possibly oral folic acid and iron supplements.

Sodium is a commonly occurring mineral and is one of the important elements in the body. Sodium ions are involved in acid-base balance, fluid balance, nerve impulse transmission, and muscle contraction. Sodium is mostly found in extracellular fluid. Sodium levels are regulated by the kidneys, which retain or eliminate sodium according to the body’s needs. Sodium interacts with potassium as part of the fluid exchange through cell membranes. Sodium is naturally present in many foods. The most common, most familiar concentrated form is sodium chloride, or table salt, which is used to flavor and preserve food. The typical American diet tends to be higher in sodium than is nutritionally required. Prepared foods such as canned soups or vegetables and frozen dinners are common in the diet of many older adults. In addition, older adults may use excessive amounts of salt to compensate for the decreased ability to perceive the taste of foods. Excessive blood levels of sodium, or hypernatremia, can cause fluid retention, which in body tissue is manifested as edema. People with hypertension, renal failure, or cardiac conditions are often placed on sodium-restricted diets, and many (especially older adults) report that food is less appetizing when prepared with reduced amounts of sodium. With less appetite, these individuals may eat less.

Potassium is the major intracellular ion in the body. Potassium ions play an important role in acid-base balance, fluid and electrolyte balance, and (with sodium) normal neuromuscular functioning. Potassium is not as abundant in the diets of older adults as are some of the other minerals. Dietary sources of potassium include citrus fruits, milk, bananas, and apple juice. Potassium deficiency, or hypokalemia, is a common problem in older adults. Many diuretic and antihypertensive medications deplete the body of potassium, as can prolonged or frequent diarrhea. Symptoms of hypokalemia include muscle weakness, anorexia, apprehension, irritability, drowsiness, depression, and disorientation. Severe muscle weakness is the most common observation related to decreased potassium levels. Hypokalemia with digitalis therapy is often a cause of cardiac arrhythmias. Because not all patients who have decreased levels of potassium demonstrate observable symptoms, nurses must check laboratory studies to verify levels of the electrolytes. Supplements are often prescribed to increase low blood potassium levels.

Zinc is a trace mineral that plays a role in protein synthesis. In adults, insufficient zinc may result in delayed wound healing, impaired immune function, lethargy, skin changes, diminished sense of smell and taste, and decreased appetite. Certain conditions, including some that are common in older adults, may result in zinc deficiency (e.g., cirrhosis of the liver, kidney disease, malignant cancers and alcoholism). Supplemental zinc may be administered. Dietary sources of zinc include meat, shellfish, and nuts.

Trace elements such as magnesium, copper, iodine, fluorine, chromium, selenium, nickel, and sulfur are necessary in very small amounts for normal body functioning. Selenium is gaining importance as an antioxidant mineral believed to promote heart health; improve tissue elasticity; and decrease the risk of colorectal, lung, and prostate cancer.

Water

Water is essential for life. Humans can survive for many days without food but not without water. Water plays a role in many aspects of normal body functioning. Water is necessary for the formation of many of the body’s secretions, including tears, perspiration, and saliva. Water aids in digestion and in transportation of electrolytes and nutrients. Water facilitates elimination of waste products and plays an important role in temperature regulation.

Approximately 60% of the average adult body is composed of water, with adult men having slightly more body fluid than do women. Older individuals typically have less body fluid than do younger adults. The total amount of body fluid decreases by approximately 8% to 10% in older adults. The amount of water in the bloodstream remains relatively constant with aging, but older adults tend to have less fluid in the intracellular and interstitial spaces than do younger people. This fluid decrease results in loss of skin turgor and leads to the wrinkled appearance that is common with aging. Decreased fluid increases the risk for fluid imbalances such as dehydration. Inadequate fluid intake can lead to altered absorption of medications, interfere with appetite and digestion, and contribute to problems with constipation. Severe dehydration can make existing medical conditions worse and can ultimately result in death. Most adults require 2000 to 3000 ml of fluid each day. Most of this is consumed as beverages such as water, tea, coffee, and juice. Solid foods, particularly fruits and vegetables, contain significant amounts of water.

Water is normally lost through urination, perspiration, respiration, and defecation. Abnormal fluid loss occurs with diarrhea, vomiting, diaphoresis, gastric suctioning, and wound drainage; essential minerals are often lost along with the water. The amount of fluid taken into the body should be in balance with the amount eliminated from the body. This is referred to as fluid balance.

Malnutrition and the elderly

In America, where obesity is an increasing problem, undernutrition and malnutrition are significant problems for the elderly. Statistics show that a large number of independent elderly— and even more institutionalized older adults—are at risk for malnutrition. Malnutrition is defined as a disorder of nutrition resulting from unbalanced, insufficient, or excessive diet or from impaired absorption, assimilation, or use of food. The risk for developing nutritional deficiencies increases with aging, but determining nutritional status is not always easy. Older adults who appear to be healthy may have unhealthy nutritional practices. An obese elderly person may be malnourished, whereas a thin elderly person may be well nourished. Studies have shown that a majority of older Americans believe that nutrition is important for good health but that they do not always follow good nutritional practices. Information from the National Council on Aging Nutritional Assessment Self-Test reveals that older adults have a disproportionately high risk for poor nutrition, which, in turn, has a negative effect on their health. Poorly nourished older adults are more likely to experience functional impairments, fatigue, loss of muscle strength, poor tissue healing, pressure ulcers, and infections. They are likely to develop more postoperative complications, spend a longer time in the hospital, and are at increased risk for death.

The Nutrition Screening Initiative, a coalition headed by the American Dietetic Association, estimated that in 2002 the number of elderly who was malnourished or at risk for malnutrition was as follows:

Other studies have yielded similar results and also report that an additional 5% to 10% of independent elderly in the community are likely to be inadequately nourished. These statistics reveal the magnitude of the problem that needs to be addressed by health care providers.

Symptoms of nutritional problems include unintentional weight loss, lightheadedness, disorientation, lethargy, and loss of appetite. The same or similar symptoms often occur with a variety of illnesses, making it difficult to determine whether the primary problem is medical or nutritional in origin. The medical diagnosis “failure to thrive” has long been used to describe infants and children who fail to grow at the expected rate. The diagnosis “geriatric failure to thrive” is being used with increasing frequency to describe elderly people who experience a pattern of symptoms, including depression, withdrawal, decreased activity, weight loss, decreased appetite, and malnutrition. This is a complex problem that requires nutritional and psychosocial interventions to stop the downward progression. Nurses working in all health care settings need to assess, plan, and implement strategies to maintain or improve the nutritional status of their elderly patients.

Factors Affecting Nutrition in the Elderly

The nutritional status of older adults living in the community is affected by physiologic, economic, and social factors. Lack of appetite is commonly reported. The reasons for this are multiple and form the basis of risk assessment. The more risk factors present, the greater the likelihood of the older person experiencing nutritional inadequacy. Overall nutritional status will be affected if any of these problems persists for a significant period of time.

Physiologic risk factors include the following:

• Chronic health factors such as COPD, CHF, arthritis, dementia, and many others can interfere with obtaining and preparing adequate nutritional food. Shopping requires physical exertion. Acts that a young, healthy person does not think about—such as lifting cans from a top shelf, reaching for something near the floor, or moving groceries into and out of a store cart—can physically exhaust an infirm or older adult. Although store personnel or other shoppers would probably help with these activities (Figure 6-3), older adults are often too embarrassed or proud to ask for help. Once food is purchased and taken home, the task of food preparation remains. Opening cans, unsealing jars, and dealing with the ubiquitous plastic wrappers on food all present daunting obstacles to the aging individual. Think of the problems that a young, healthy person may have with current packaging, and then imagine performing the same tasks with decreased muscle strength, arthritis, or other age-related problems.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree