CHAPTER 9

Lower Extremity Arterial Disease

Mary Sieggreen

M. Eileen Walsh

First Edition Author: Roberta Ronayne; combined with Arterial Ulcers by Mary Sieggreen

OBJECTIVES

1. Identify risk factors for the development of lower extremity peripheral artery disease (PAD).

2. Discuss preventive measures for acute and chronic PAD.

3. Describe the etiology of arterial ulcers and the differential characteristics of arterial ulcers.

4. Identify subjective and objective assessment data related to PAD and arterial ulcers.

5. Compare tests and procedures used in the evaluation and diagnosis of PAD of the lower extremity.

6. Describe medical and surgical treatment options for individuals with PAD of the lower extremities.

7. Identify interventions to treat arterial ulcers, including aggravating and alleviating factors for arterial ulcers.

8. Discuss nursing interventions related to patient teaching, health promotion, disease prevention, preoperative care, postoperative care, and home care.

Introduction and Overview

Peripheral artery disease (PAD), commonly referred to as arterial occlusive disease, results from an acute or chronic occlusion that causes narrowing of arteries, resulting in decreased blood flow (ischemia) to the lower extremities. Symptoms of occlusion are intermittent claudication which is typically described as a muscle cramp or ache with activity, rest pain, and ulceration. Atherosclerosis is the underlying process that precipitates the onset and progression of PAD. Individuals with PAD may have other systemic atherosclerotic problems such as coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, and renal insufficiency. Other comorbidities include chronic renal failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Aponte, 2011; Creager & Libby, 2011; Hirsch et al., 2007).

The incidence of PAD increases with age. There is a higher prevalence in males and those over 70 years of age. The true incidence of chronic disease, however, is difficult to determine as many people are asymptomatic and others fail to report symptoms as they attribute these symptoms to the normal aging process. Other individuals tolerate the disease by modifying contributing lifestyle risk factors (Hirsch et al., 2007; Verma, Prasad, Elkadi, & Chi, 2011).

Atherosclerotic disease tends to occur in a symmetric fashion by respective segments of the arterial tree: aortoiliac, femoropopliteal, and tibial-peroneal disease. The signs and symptoms of chronic disease occur over time as this allows for the development of collateral vessels around the obstruction. Although PAD is not a leading cause of death, it significantly impacts quality of life, mobility, and limb loss (Collins et al., 2011). Mortality is primarily due to coexisting health problems (Gandhi, Weinberg, Margey, & Jaff, 2011; Jaffery et al., 2009).

Acute arterial occlusion results from a sudden interruption of blood supply. Critical limb ischemia can develop within hours and threaten both limb and life. With acute arterial occlusion, hemodynamic and metabolic consequences are more severe than with chronic disease (Jaffery et al., 2009; Muir, 2009).

Arterial ulcers usually occur at the most distal end of the arterial tree. Arterial ulcers are also called ischemic ulcers because they are caused by diminished arterial blood flow to the tissues. Ulcers may be the result of a precipitating event such as a trauma injury which fails to heal. Arterial occlusive disease including atherosclerosis, arterial vasospasm, or arterial inflammatory disease may be the underlying cause of ischemia. These ulcers are painful and debilitating. There may be substantial loss of tissue and in severe situations can be limb threatening (Holtman & Gahtan, 2008).

I. Anatomy

I. Anatomy

A. Arterial Wall–Arteries Are Composed of Three Histologic and Functional Layers: Intima, Media, and Adventitia

1. Intima

a. Innermost layer lining the lumen of the arterial wall

b. Single layer of endothelial cells providing smooth lining

c. Separated from the media by the internal elastic membrane

d. Receives nutrients from the arterial lumen by diffusion

2. Media

a. Middle layer of thick smooth muscle cells, collagen, and elastic fibers

b. Regulates vessel diameter by dilation and constriction

c. Inner area receives nutrients from the arterial lumen by diffusion; outer area receives nutrients from the vasa vasorum, the small blood vessels that penetrate the arterial wall

d. Separated from the adventitia by an external elastic membrane

3. Adventitia

a. Outermost layer of the artery

b. Composed of connective tissue, collagen, and elastic fibers

c. Provides majority of strength to the arterial wall and maintains its shape

d. Receives nutrients from the vasa vasorum, the small blood vessels that penetrate the arterial wall

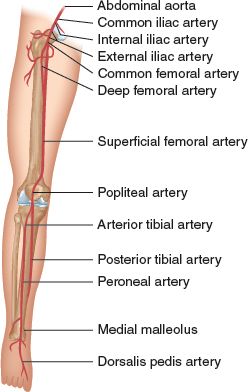

B. Arteries of the Lower Extremity (see Figure 9-1)

1. Distal aorta branches into the internal and external common iliac arteries

a. Internal iliac artery (also called the hypogastric artery) enters the pelvic cavity and divides into branches that supply

1. Pelvic viscera (urinary bladder, uterus, vagina, and rectum)

2. Muscles of the gluteal and lumbar regions

3. Walls of the pelvis

4. External genitalia

5. Middle region of thigh

b. External iliac arteries pass under the inguinal ligament and divide into the common femoral artery upon entering the thigh, supply the muscles and skin of the lower abdominal wall which branches into

1. Superficial femoral artery

2. Deep femoral or profunda femoris artery: supplies muscles of the thigh

3. Popliteal artery: arises from the superficial femoral artery as it passes through the adductor hiatus in the distal thigh. Divides into

a. Anterior tibial artery, lies between the tibia and fibula; supplies muscles and skin in the front of the leg; becomes the dorsalis pedis artery at the ankle joint

b. Posterior tibial artery, continues down the back of the leg into the ankle; divides into the medial and lateral planter arteries to supply the sole of the foot and form the plantar arch

c. Peroneal artery, supplies structures in the lateral aspect of the leg

FIGURE 9.1 Lower extremity arterial anatomy.

II. Pathophysiology

II. Pathophysiology

The underlying etiology of arterial disease is varied. A prolonged decrease in blood flow may result in acute or chronic ischemia of the skin, muscles, nerves, and tissues

A. Acute Arterial Occlusion/Acute Limb Ischemia

1. Sudden decrease or worsening in limb perfusion causing a potential threat to loss of limb

2. Collateral arteries are usually absent

3. Critical ischemia develops within hours and is associated with the following conditions

a. Irreversible hypoxia to skeletal muscle or peripheral nerves occurs within 4 to 6 hours

b. Skin and subcutaneous tissue remain viable for longer periods of time due to differences in tissue tolerance to ischemia

4. Outcome depends on duration of tissue ischemia, site of obstruction, extent of thrombus propagation, adequacy of collateral circulation, and hemodynamic state of the patient

5. Signs and symptoms occur distal to the area of obstruction and vary depending on the level and severity of obstruction and adequacy of circulation

6. Paralysis is a late sign which indicates that the limb already has necrotic muscle and will not regain function. Often an amputation of the limb is needed

B. Chronic Arterial Occlusive Disease

1. Ischemia alters perfusion to the lower extremity; compensatory mechanisms initiated to counteract the ischemia include

a. Vasodilation

b. Development of collateral circulation

c. Anaerobic metabolism to meet tissue needs

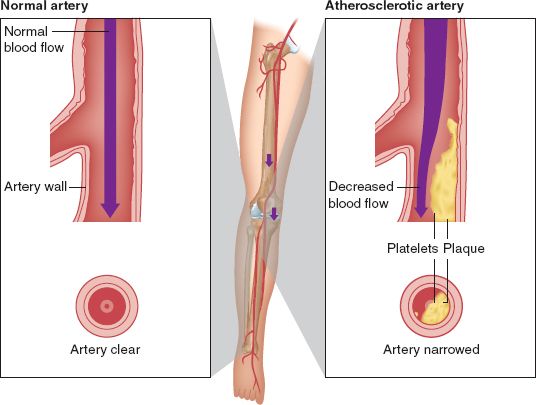

2. Atherosclerosis (Carroll, 2008). See Figure 9-2

a. The most common cause of diminished arterial blood flow

b. Characterized by the local accumulation of lipids, hemorrhage, fibrous tissue, and calcium deposits

c. Exact cause of atherosclerosis is not known; it can begin to develop during childhood

1. Fatty streak formation: appears as thin yellow lines and spots, slightly raised on the intima of the artery; reversible at this stage

2. Fibrous plaques: more permanent lesions consisting of a lipid core surrounded by a capsule of elastic and collagenous tissue; causes loss of elasticity; occurs at arterial bifurcations

3. Complicated lesions resulting in necrosis of the plaque and surface ulceration

d. Risk factors include age, gender, family history, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, sedentary life style, obesity, and stress

FIGURE 9.2 Normal artery and atherosclerosis of an artery.

C. Arterial or Ischemic Ulcers

1. Usually the most distal end of the arterial tree

2. Occur most often in the lower extremities although they may be found at the tips of the fingers in vasospastic arterial disorders

3. Common complication of arterial occlusive disease

4. High prevalence among elderly, smokers, those with end stage renal disease, diabetes, and collagen vascular disease

5. Nonhealing foot ulcer may be the first indication that an individual has atherosclerosis

6. Altered healing occurs due to inadequate blood perfusion to the tissue. The increase in local metabolic needs for ulcer healing cannot be met

III. Etiology or Precipitating Factors

III. Etiology or Precipitating Factors

A. Acute Arterial Occlusion/Acute Limb Ischemia Results from

1. Thrombosis

a. Obstruction from local factors such as thrombosis of narrowed atherosclerotic artery or popliteal aneurysms

b. Obstruction from systemic factors due to decreased cardiac output from heart failure, dysrhythmias or shock, and hematologic abnormalities

2. Embolus (Chan & Cheng, 2011)

a. Fragments of a thrombus migrate to another area; may be atheromatous plaque or tumor

b. Commonly lodge at bifurcations of major arteries particularly in the lower extremities (aorta, femoral, iliac, popliteal) or areas where vessel suddenly tapers or branches

1. Saddle embolus: embolus that lodges at bifurcation of aorta

2. 50% of emboli lodge at the common femoral bifurcation

3. 5% to 30% emboli lodge in distal aorta and iliac arteries

c. Source of embolus

1. Cardiac: atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarction, cardioversion, atrial myxoma, mitral stenosis, mural thrombus from myocardial infarction

2. Noncardiac: originate from proximal atherosclerosis, such as ulcerated aortic atheroma or an aneurysm

3. Trauma

a. Musculoskeletal injuries: fractures (femur, tibial plateau), dislocations

b. Crushing/penetrating injuries

c. Intimal disruption with subsequent thrombosis

d. Laceration or transection of artery

e. Iatrogenic trauma from percutaneous catheters used for diagnostic or therapeutic procedures

B. Chronic Arterial Occlusion from

1. Atherosclerosis

2. Arteritis

3. Vasospastic disorders

4. Fibromuscular dysplasia

IV. Assessment

IV. Assessment

Clinical manifestations of arterial occlusive disease develop below or distal to the site of obstruction. The primary factors determining the clinical presentation of lower extremity arterial diseases include the site of obstruction, onset (acute or chronic), collateral circulation, adequacy of distal arteries, and hemodynamic state (O’Connor & Ingram, 2011)

A. Risk Factors and Primary Prevention

1. Nonmodifiable (Muir, 2009; Na, Wang, Kirsner, & Federman, 2011; Oka, 2006; Treat-Jacobson & Walsh, 2003)

a. Age: prevalence increases with age in males and females; increasing age >70

b. Gender: more common in men and postmenopausal women

c. Family history: increased predisposition if positive family history for PAD or any associated concomitant disease/risk factors

2. Modifiable

a. Smoking (Verma et al., 2011)

1. PAD occurs 8 to 10 years earlier in smokers than in nonsmokers

2. Nicotine causes vasospasm, arterial constriction, endothelial injury, alteration of platelets, increased blood viscosity, and increases blood pressure

3. Smoking cessation is associated with a rapid decline in the incidence of intermittent claudication

b. Diabetes (Chou et al., 2008; Schaper et al., 2012)

1. Increases risk of PAD two- to fourfold; PAD is twice as common in diabetics compared with nondiabetics; and develops at an earlier age

2. Impairs arterial wound healing

3. Increases risk for infection and gangrene

4. Causes peripheral neuropathy

c. Dyslipidemia—secondary to atherosclerosis; see Chapter 8, Vascular Medicine and Rehabilitation

d. Hypertension—secondary to atherosclerosis; blood pressure increases as blood flows through narrowed vessels

e. Coronary artery disease—increases mortality caused by myocardial ischemia

f. Obesity

g. Sedentary lifestyle—increases incidence of other risk factors

h. Hyperhomocysteinemia

B. Patient History—Acute Arterial Occlusion/Acute Limb Ischemia

1. Subjective findings

a. Chief complaint: sudden onset of the six P’s; not all need to be present (see Table 9-1)

TABLE 9.1 The Classic 6 P’s: Signs and Symptoms of Acute Arterial Occlusion

| Pain—severe and constant, may be masked as a result of sensory deficits |

| Pallor—pale, yellowish tone to extremity below site of occlusion; extremity quickly appears waxy due to complete emptying and vasospasm of the arterial circulation |

| Pulselessness—absence of a pulse |

| Poikilothermia—coolness |

| Paresthesia—unusual or unexplained tingling, pricking, or burning sensation of skin. A sign indicating potential irreversibility. Caused by reduced blood supply to distal nerve fibers. Proprioception and light touch are lost early |

| Paralysis—loss of voluntary movement, a sign indicating potential irreversibility |

b. Compartment syndrome/reperfusion injury: swelling within the osteofascial compartments of the limb, which causes increased intracompartmental pressure, resulting in decreased vascular perfusion; see Table 9-2

c. Metabolic complications: acidosis, hyperkalemia, and renal failure secondary to myoglobinuria

2. Objective findings

a. Past history of cardiac disease including dysrhythmias or myocardial infarction

b. Previous history of peripheral vascular disease, thrombosis

c. Recent episode of hypotension

TABLE 9-2 Signs and Symptoms of Compartment Syndrome

| Pain disproportional to injury |

| Tenderness and tenseness of compartment |

| Pain on passive stretching |

| Decreased muscle strength within compartment |

| Decreased simple touch perception |

| Decreased sensation of nerves in compartment |

| Pulses: may be normal or diminished; absent in late stages |

C. Patient History—Chronic Arterial Occlusive Disease

1. Subjective findings

a. Chief complaint: intermittent claudication or ache involving the hip, buttocks, thigh, and calf with activity; frequently described as cramping, fatigue, or tired; may be unilateral or bilateral; may also present with atypical leg pain (McDermott et al., 2010)

1. Induced by exercise (e.g., walking a predictable distance) and relieved by short periods of rest

2. Often mistaken as a normal consequence of aging, an orthopedic problem, or sciatic nerve

3. Distance walked before onset of pain is usually consistent, thus it is called reproducible. The shorter the distance walked, the more severe the disease process

b. Rest pain

1. Occurs with severe disease with extremity resting in a horizontal position

2. Usually confined to the forefoot and metatarsal head (toes)

3. Pain is aggravated by elevation

4. Partial or total relief is obtained by dangling the legs over the side of the bed, which increases arterial pressure due to gravity but may lead to edema

5. Associated with limb-threatening ischemia because blood flow is insufficient to meet even minimal metabolic requirements

6. Associated with gangrene and ulcers that do not heal

7. Coolness of the foot and/or limb

8. May require amputation

2. Objective findings

a. Positive history of atherosclerosis such as coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, and renovascular disease

b. Positive family history of atherosclerosis, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia

c. Decreased functional ability to perform activities of daily living

D. Physical Examination—Clinical Manifestations of Disease Vary Depending on Level and Severity of Obstruction and Adequacy of Collateral Circulation. During Each Phase of Assessment One Limb Should Be Compared to the Other

1. Inspection

a. Skin color changes

1. Pallor on elevating limb 30 to 40 degrees

2. Dependent rubor: deep red color when limb in dependent position. Color change reflects oxygen saturation and blood flow in capillary venous plexus of skin

b. Temperature changes: coolness distal to site of occlusion

c. Trophic changes: hair loss on affected limb; thin, smooth shiny skin; thick brittle toes nails, tapering toes; skin breakdown, ulceration, and gangrene due to nutritional changes

d. Size and symmetry of both limbs for muscle atrophy, edema, presence of scars from previous surgery, and absence of limb

e. Decreased capillary refill

f. Edema usually absent; if present, may be related to dependence

g. Arterial ulcers

1. Color of surrounding skin and ulcer base is usually pale, increasing with elevation

2. The skin surrounding the ulcer is shiny and smooth and appears taut, especially if the arterial disease is chronic

3. Loss of hair occurs in conditions of chronic ischemia but an ulcer may be caused by arterial insufficiency even with hair present

4. Gangrene may be present in the ulcer bed or in the surrounding skin

5. Blue or purple patches of skin may indicate new ischemic areas that will soon become black

6. Moist dead tissue may be present in the wound bed. This can be yellow or grey

7. Ulcer characteristics are as follows

a. Arterial ulcer location is at the distal end of the arterial tree. Ulcers are commonly found between and on the tips of toes, around the ankle, over the malleolus, or on the foot over the phalangeal heads, or at an area of trauma

b. Arterial ulcer wound bed is usually dry and may be desiccated unless there is an infection present

c. Arterial ulcer size depends on the precipitating factors. It may be small and punched-out looking or may cover a large area resulting from trauma. A nonhealing surgical incision in an ischemic limb may be considered an arterial ulcer

2. Palpation

a. Assess: femoral, popliteal, posterior tibial, dorsalis pedis pulse for presence and quality (present, diminished, or absent)

b. Use Doppler to determine if signals are present

c. Posterior tibial and dorsalis pedis pulses may be absent due to congenital anatomic variation

d. Pedal pulses may be present with intermittent claudication but disappear with exercise

e. Temperature

1. Use back of hand to assess skin temperature in limbs

2. Temperature demarcation may be felt at the skeletal segment distal to the site of arterial occlusion

3. Asymmetric coolness is suggestive of arterial insufficiency; symmetric coolness indicates vasoconstriction or aortic obstruction

f. Arterial ulcer

1. Skin around the ulcer may feel cooler than skin on other parts of body

2. Palpate the surrounding tissue for induration indicating cellulitis

3. Palpate pulses

4. Palpate the wound bed for tunneling or undermining. A soft boggy wound base indicated deeper necrotic tissue and possible infection with liquefaction of soft tissue necrosis

3. Auscultation

a. Assess femoral and iliac arteries for bruit which is the sound associated with turbulent blood flood

b. Bruit may help to localize the stenosis and differentiate between iliac and superficial femoral artery disease

1. Auscultate using bell of stethoscope

2. Higher pitch indicates more severe occlusion

3. Superficial femoral artery stenosis may be present when the superficial femoral artery is compressed with the stethoscope

E. Considerations Across the Life Span

1. Young adulthood: occlusive atherosclerosis usually not seen in youth although underlying pathologic changes have begun. Provide education about modifiable risk factors and influence on disease progression

2. Pregnancy: medical and surgical management may need to be altered during pregnancy

3. Elderly: PAD is more prevalent during the later years of life and significantly affects quality of life. Recognition of pain may be complicated by physical or cognitive impairments, ongoing drug therapy, or social isolation. Self-care may be hampered by loss of vision

V. Pertinent Diagnostic Testing

V. Pertinent Diagnostic Testing

A. Laboratory Tests

1. Routine electrolytes; blood urea nitrogen and creatinine—determine if renal insufficiency

2. Complete blood count

3. Electrocardiogram

4. PTT, PT/INR, platelets, fibrinogen—determine if coagulation disorder; potential for thrombus formation

5. Lipid panel, including total cholesterol, HDL, triglycerides, and LDL–determine dyslipidemia

6. Blood sugar and glycosylated hemoglobin levels—determine if diabetes

B. Noninvasive Diagnostic Test (Azam & Carman, 2011; Harrison, Lin, Blakley, & Tanaka, 2011; Owen & Roditi, 2011)

1. Ankle–brachial pressure index (ABI) (Mohler & Giri, 2008).

a. Provides objective data on perfusion or arterial blood to lower extremities

b. Portable, can be done at bedside

c. Ankle systolic pressure is normally equal to or slightly higher than brachial systolic pressure; a decrease in pressure indicates arterial stenosis

d. Assess ankle pressure at the dorsalis and posterior tibial arteries

e. Divide the highest ankle pressure by the highest brachial pressure

f. Any decrease in pressure indicates impaired arterial flow

1. Normal—1.40 to 0.90

2. Abnormal <0.90

3. >1.40 noncompressible vessels

2. Toe systolic pressure index (TSPI) (Mohler & Giri, 2008)

a. Appropriate for diabetics: 5% to 10% of diabetics have incompressible arteries

b. Helps predict healing of toe and forefoot wounds and amputation sites

c. Measurements taken at the great toe to assess arterial flow to the pedal or digital arteries

d. Normal ≥60 mm Hg; reduced >30, <60 mm Hg; ischemic <30 mm Hg

3. Treadmill exercise testing

a. Provides functional assessment of walking distance

b. Determines initial claudication time or distance and absolute claudication time or distance, sometimes called peak walking time or distance

c. Comparison of pre- to postexercise ABI provides objective information

4. Duplex ultrasonography

a. Provides detailed images of stenosis, occlusion, and arterial diameter

b. Provides hemodynamic information to assist in grading severity of stenosis

c. Aids in decisions regarding treatment plan and options

d. Assists with vein mapping if surgical revascularization is needed

5. Pulse volume recordings

a. Assists in locating the site of occlusion in the common femoral, popliteal, dorsalis pedis, and posterior tibial arteries

b. Requires segmental limb pressures to quantify arterial flow

1. Pressures taken at dorsalis pedis, posterior tibial arteries, thigh, popliteal segment

2. Highest brachial pressure is used for comparison

3. Systolic pressure in leg is normally equal to or slightly higher than the systolic arm pressure

4. Systolic pressure drops proportionally to severity of disease

a. Ratio changes within a 0.15 range are considered within normal limits

6. Transcutaneous partial tension of oxygen (TCPO2)

a. Measures oxygen quality in microcirculation

b. Measures effectiveness of interventions

c. Helps to determine level of amputation

C. Invasive Tests

1. Arteriography

a. Assess arterial anatomy; depicts aorta, iliac, femoral, popliteal, and tibial artery segments

b. Identifies location and extent of arterial obstruction

c. Provides information on status of runoff vessels

d. Common femoral artery is the most common access site

e. Performed before endovascular procedures (transluminal angioplasty) or operative procedure and in patients who have suspected graft occlusion or pseudoaneurysm

f. Associated with complications

2. Digital subtraction angiography (DSA)

a. Used to predict success of bypass grafting

b. Provides information about the best site for proximal inflow and distal outflow and the presence of distal runoff to support a graft

3. Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA)

a. Is based on MRI mechanisms and techniques

b. Visualizes vasculature of lower extremities without contrast media

c. May be used in combination with ultrasound

4. Computed tomography (CT)

a. Provides accurate staging of abdominal aortic aneurysm, postoperative problems (graft infection, graft occlusion, hemorrhage, and abscess)

b. Allows direct depiction of the arterial wall; accurately defines processes and structures around vessel wall that indicate disease

c. May require the use of contrast medium

D. Special Procedures–Based on Patient Presentation, Health History, and Planned Intervention

VI. Medical Management (see Chapter 8, Vascular Medicine and Rehabilitation)

VI. Medical Management (see Chapter 8, Vascular Medicine and Rehabilitation)

Treatment is based on severity of symptoms and overall medical condition of the patient

Most patients with chronic PAD can be managed conservatively with an exercise program, modification of risk factors, and pharmacologic therapy to treat symptoms and associated concomitant diseases (Aronow, 2010; Catapano et al., 2011; Paravastu, Mendonca, & Da Silva, 2008; Treat-Jacobson & Walsh, 2003)

A. Chronic PAD

1. Risk factor reduction: smoking, diabetes, cholesterol levels, high blood pressure, sedentary lifestyle, control of other diseases

2. Walking Program (Collins et al., 2011).

a. Helps control disease, improve quality of life, and pain-free total walking distance

b. Improves oxygen uptake and use by muscle

c. Promotes development of collateral arteries

1. Collateral arteries are preexisting pathways that enlarge when flow through a parallel major artery is reduced; they are smaller, longer, and more numerous than the major arteries they replace

2. Resistance through collateral vessels is greater than through normal artery, which limits the increase in flow occurring with exercise

3. Vascular rehabilitation program (Gardner & Afaq, 2008; Murphy et al., 2012)

a. Structured exercise program specific to improving symptoms of intermittent claudication

b. Incorporates techniques for physical reconditioning, education, and risk factor modification

c. Patient advised to walk to the limit of discomfort, stop and resume walking

d. Promotes development of collateral vessels in the affected leg

e. Minimum three times a week

f. Gradual increase in exercise duration and intensity based on symptoms

4. Protecting skin

a. Use foot device to protect feet and toes, provide warmth resulting in vasodilation and increases circulation to extremities

b. Prevent bed linens from causing pressure

c. Use gauze between toes to prevent skin-to-skin contact

d. Use gauze between toes with ulcers that may have exudate

5. Pain management

a. Stop activity and rest

b. Avoid elevating limb

c. Take prescribed analgesia

6. Medications: few medications have demonstrated efficacy in adequately designed, placebo-controlled trials

a. Hemorrheologic agents: pentoxifylline (Trental)

1. Increases erythrocyte flexibility; reduces blood viscosity and increases volume of oxygenated blood to ischemic muscle; inhibits platelet aggregation

2. Therapeutic effects occur after 4 to 8 weeks of therapy (400 mg t.i.d) with meals

3. Current research has found a limited decrease in pain associated with intermittent claudication and does not support the widespread use of this drug

b. Cilostazol (Pletal) (100 mg b.i.d) (Robless, Mikhailidis & Stansby, 2008)

1. Has antiplatelet and vasodilator effects

2. Acts directly on vascular smooth muscle

3. Increases pain-free walking distance

4. May increase HDL and decrease triglyceride levels

5. Long-term effects and risks are not established

6. Contraindicated in patients with heart failure

c. Antiplatelets: acetylsalicylic acid (Aspirin) and clopidogrel (Plavix)

1. Reduce platelet aggregation and thrombus formation

2. Reduce risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality associated with myocardial infarction, stroke, and vascular death

3. May reduce rate of vascular graft occlusion

d. Other medications

1. Vasodilators: do not increase blood flow to an ischemic limb or to exercising muscles

2. Vascular endothelial growth factor: experimental

3. Vitamin E: insufficient evidence

VII. Surgical Management

VII. Surgical Management

A. Management of Acute Ischemia

Factors to be considered in choosing an intervention include location and anatomy of lesion, duration of acute limb ischemia, type of clot, patient-related risks, surgery-related risks, and contraindications to thrombolysis

1. Bed rest

2. Anticoagulation

a. Alters viscosity of blood and potentiates blood flow through narrowed vessels

b. Prevents propagation of thrombus distal and proximal to occlusion; proliferation of new emboli

c. Delay in initiation of therapy or inadequate treatment may result in limb loss, damage to vital organs, or death

d. Types

1. Intravenous heparin (unfractionated)–systemic heparinization with a fixed-dose bolus (5,000 to 10,000 U boluses) or weight-based dosing (80 U/kg) followed by continuous drip to maintain the APPT ratio between 1.5 and 2.5 times the control. Requires frequent and consistent monitoring of APTT levels

2. Parenteral

a. Subcutaneous heparin: has a slower, erratic absorption; is less precise than Intravenous administration; usually administered b.i.d

b. Low molecular weight heparin derivatives

• Less risk of bleeding complications with comparable anticoagulation affects than heparin

• Administered subcutaneously

• Does not require laboratory monitoring

3. Oral anticoagulation: warfarin (Coumadin)

a. Good for long-term anticoagulation

b. Requires frequent monitoring of INR/PT levels

c. Requires dosage adjustments[Q5]

3. Thrombolytic therapy: for example, alteplase, streptokinase, and t-PA (tissue plasminogen activators) (Lipsitz & Kim, 2008)

a. May be used alone or in conjunction with surgical intervention to treat recently formed arterial and bypass graft occlusions

b. Interventional angiography used to inject thrombolytics into failed grafts

c. Associated with a higher frequency of hemorrhagic complications

d. Contraindicated in patients who had a recent surgery or stroke and patients who have severe uncontrolled hypertension

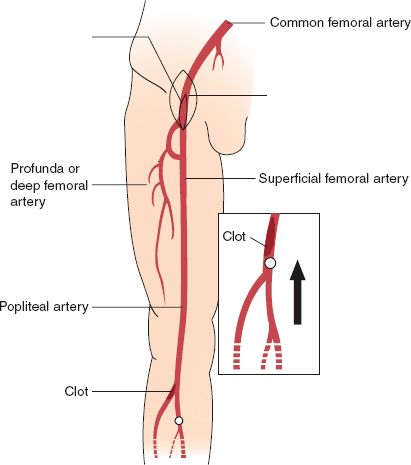

4. Surgery

a. Embolectomy, see Figure 9-3

1. Extraction of embolus using an embolectomy catheter with balloon at tip

2. When tip is beyond obstruction, balloon is inflated, and catheter and embolus are withdrawn

3. Can be done with local anesthesia

4. May require use of heparin and warfarin (Coumadin) postoperatively

FIGURE 9.3 Thrombectomy/embolectomy of leg.