Over the past two decades, educators as well as government officials, employers, and media experts have focused interest on and expressed concern about literacy in the U.S. population. Adult illiteracy continues to be a major problem in this country despite public and private efiorts at all levels to address the issue through testing of literacy skills and development of literacy training programs.

Today, the fact remains that many individuals do not possess the basic literacy abilities required to function effectively in a technologically complex society. Many adult citizens have difficulty reading and comprehending information well enough to be able to perform such common tasks as filling out job and insurance applications, interpreting bus schedules and road signs, completing tax forms, applying for a driver’s license,

registering to vote, and ordering from a restaurant menu (

Weiss, 2003).

In the early 1980s, President Ronald Reagan launched the National Adult Literacy Initiative, which was followed by the United Nations’ declaration of 1990 as International Literacy Year (

Belton, 1991;

Wallerstein, 1992). In 1992, the U.S. Department of Education conducted the National Adult Literacy Survey (NALS), which revealed a shockingly high prevalence of illiteracy in the country (

Weiss, 2003;

Weiss et al., 2005;

Zarcadoolas, Pleasant, & Greer, 2006). Since then, awareness about illiteracy—once thought previously to be a problem mainly confined to developing countries—has taken on new meaning in the United States (

Lasater & Mehler, 1998;

Schwartzberg, VanGeest, & Wang, 2004).

However, in light of the relatively recent attention given to this problem in the last 20 years, it must be acknowledged that Literacy Volunteers of America and Lauback Literacy International have for many decades served as advocates for the most marginalized adult population both in the United States and around the globe. Today, ProLiteracy (www.proliteracy.org), which was formed in 2002 from the merger of these two entities, is the world’s largest organization targeting adult literacy. It supports 1100 literacy programs across the United States and partners with 50 other organizations in 34 developing countries worldwide (

ProLiteracy, 2012). Syracuse, New York, has been the birthplace of all three of these organizations, and central New York is now recognized as the capital of the literacy movement. America’s literacy problem has become a national crisis because for too long this country has ignored those who are unseen and unheard (

Wedgeworth, 2007).

Particularly in the past 10 years as a result of the NALS report, nursing and the health professions literature has focused significant attention on the effects of patient illiteracy on healthcare delivery and health outcomes. Today, the emphasis is on health literacy—that is, the extent to which Americans can read and comprehend health information well enough to function successfully in a healthcare environment and make appropriate decisions for themselves. Although a great deal more research needs to be done on the causes and effects associated with poor health literacy as well as the methods available to screen and teach patients, much has been learned about the magnitude and consequences of the health literacy problem (

Friedman & Hoffman-Goetz, 2008;

Gazmararian, Curran, Parker, Bernhardt, & DeBuono, 2005;

Paasche-Orlow & Wolf, 2007a;

Pignone, DeWalt, Sheridan, Berkman, & Lohr, 2005).

Healthy People 2010 and

Healthy People 2020 both identified limited health literacy as one of the nation’s top public health agenda concerns (

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2000,

2012). In 2006, several agencies of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services joined forces to establish a health literacy workgroup. In the fall of 2010, this highly diverse workgroup released the

National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy, also known as NAP or the “Action Plan” (

Baur, 2011).

The NAP was created to provide guidance to organizations, professionals, policymakers, communities, individuals, and families in identifying actions to take to improve the widespread pandemic of limited health literacy facing not only the United States, but other countries worldwide (

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010b). The NAP is not just a report on the state of the problem—it is an urgent request to identify, select, and use strategies that have the greatest potential to produce effective, measurable improvements in health literacy (

Speros, 2011).

Nurses are in a unique position that enables them to act as advocates for and empower each client to obtain, understand, and act on information provided to them. Many of the NAP strategies highlight actions that particular organizations or professions can take to further these

goals. By focusing on health literacy issues and working together, nurses can improve the accessibility, quality, and safety of health care provided, reduce costs, and improve the health and quality of life for millions of people in the United States.

The NAP envisions a society that (1) provides everyone with access to accurate and actionable health information, (2) delivers person-centered health information and services, and (3) supports lifelong learning and skills to promote good health. Furthermore, the Action Plan highlights seven goals that will improve health literacy (

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010):

1. Develop and disseminate health and safety information that is accurate, accessible, and actionable

2. Promote changes in the healthcare system that improve health information, communication, informed decision making, and access to health services

3. Incorporate accurate, standards-based, and developmentally appropriate health and science information and curricula in child care as well as education through the university level

4. Support and expand local efforts to provide adult education, Englishlanguage instruction, and culturally and linguistically appropriate health information services in the community

5. Build partnerships, develop guidance, and change policies

6. Increase basic research and the development, implementation, and evaluation of practices and interventions to improve health literacy

7. Increase the dissemination and use of evidence-based health literacy practices and interventions

These goals cannot be achieved by a single group or organization. Instead, meeting the goals of the NAP will require intense collaboration, both challenging and empowering individuals and communities to change the health system to meet the needs of specific populations.

Table 7-1 highlights the recent strides made in the United States in relation to health literacy.

With respect to the subject of literacy, the nurse educator’s attention specifically focuses on adult client populations. Literacy levels are not an issue in teaching staff nurses or nursing students because of their level of formal education. However, literacy levels remain a concern if the audience for in-service programs includes less educated, more culturally and socioeconomically diverse support staff (

Hess, 1998) or if a member of the audience has been diagnosed with a learning disability, such as dyslexia.

What must be of particular concern to the healthcare industry are the numbers of consumers who are illiterate, functionally illiterate, or marginally literate. Researchers have discovered that people with poor reading and comprehension skills have disproportionately higher medical costs, increased number of hospitalizations and readmissions, and more perceived physical and psychosocial problems than do literate persons (

Baker, Parker, Williams, & Clark, 1998;

Baker, Williams, Parker, Gazmararian, & Nurss, 1999;

DeWalt, Berkman, Sheridan, Lohr, & Pignone, 2004;

Sudore, Yaffe, et al., 2006;

Weiss, 2003;

Weiss et al., 2005).

In today’s world of managed care, the literacy problem is perceived to have grave consequences. Clients are expected to assume greater responsibility for self-care and health promotion, yet this expanded role depends on increased knowledge and skills. If people with low literacy abilities cannot fully benefit from the type and amount of information they are typically given, they cannot be expected to maintain health and manage independently. The result is a significant negative impact on the cost of health care and the quality of life (

Kogut, 2004;

Levy & Royne, 2009;

Pignone et al., 2005;

Williams, Davis, Parker, & Weiss, 2002;

Wood, Kettinger, & Lessick, 2007).

Traditionally, healthcare professionals have relied heavily on printed education materials (PEMs) as a cost-effective and time-efficient means to communicate health messages. An assumption was made that the written materials commonly distributed to clients were sufficient to ensure informed consent for tests and procedures, to promote compliance with treatment regimens, and to guarantee adherence to discharge instructions.

Only recently have healthcare providers begun to recognize that the scientific and technical terminology inherent in the ubiquitous printed teaching aids constitutes a bewildering set of written instructions little understood by the majority of people (

Ache, 2009;

Adkins, Elkins, & Singh, 2001;

Morrow, Weiner, Steinley, Young, & Murray, 2007).

Kessels (2003) points out that 40% to 80% of medical information provided by health professionals is forgotten immediately, not just because medical terminology is too difficult to understand, but also because delivery of too much information leads to poor recall. Furthermore, half of the information remembered is incorrect. Unless education materials are written at a level and style appropriate for their intended audiences, clients cannot be expected to be able or willing to accept responsibility for self-care.

An essential prerequisite for implementing health education programs is to know the literacy skills of audiences for whom these programs are intended (

Quirk, 2000). Yet calls for assessment of literacy and recommendations for appropriate interventions for clients with poor literacy skills have largely been ignored. Health professionals, including nurses, are sometimes reluctant to conduct a clinical assessment of literacy skill or place this information in the health record for fear of embarrassing or stigmatizing the client (

Paasche-Orlow & Wolf, 2007b). Therefore, even though illiteracy and low literacy are quite prevalent in the U.S. population, problems with literacy frequently continue to go undiagnosed (

Doak, Doak, & Root, 1996;

Zarcadoolas et al., 2006).

This chapter examines the magnitude of the literacy problem, the myths associated with it, and the factors that influence literacy levels. It emphasizes the important role that nurses play in assessing clients’ literacy skills and the effects of reading and health illiteracy on the well-being of the public. In addition, the formulas and tests used to evaluate readability of printed tools and to assess clients’ comprehension and reading skills are reviewed, specific guidelines are put forth for writing effective health education materials, and teaching strategies are recommended as a means for breaking down the barriers of illiteracy.

DEFINITION OF TERMS

For many years, there was no clear agreement of what it meant to be literate in U.S. society. A literate person was loosely described as someone who possessed socially required and expected reading and writing abilities, such as being able to sign his or her name and read and write a simple sentence. Over time, performance on reading tests in school became the conventional method to measure grade-level achievement.

Because it is difficult, if not impossible, to measure reading abilities on a population-wide basis, the U.S. Bureau of the Census continues to this day to use the number of years of schooling attended to define literacy levels (

Giorgianni, 1998). This method remains an imprecise means of estimating someone’s true reading skills. Many researchers have found that the reported grade level achieved in school is an inadequate predictor of reading ability (

Chew, Bradley, & Boyko, 2004;

Doak et al., 1996;

Weiss, 2003;

Winslow, 2001).

In the United States, the term

literacy is generally defined as the ability to read and speak English (

Andrus & Roth, 2002). In the 1992 NALS, the U.S. Department of Education defined literacy as “the ability to use printed and written information to function in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential” (

National Center for Education Statistics, 1993, p. 6).

Prose tasks, which measure reading comprehension and the ability to extract themes from newspapers, magazines, poems, and books

Document tasks, which assess the ability of readers to interpret documents such as insurance reports, consent forms, and transportation schedules

Quantitative tasks, which assess the ability to work with numerical information embedded in written material, such as computing restaurant menu bills, figuring out taxes, interpreting paycheck stubs, or calculating calories on a nutrition checklist

Most recently the NAP defined literacy as a set of reading, writing, basic math, speech, and comprehension skills and further adds that

numeracy is a part of literacy, implying aptitude with basic probability and numerical concepts.

Overwhelmingly, those persons with limited literacy also have limited skills in numeracy (

Andrus & Roth, 2002;

Doak et al., 1996;

Fisher, 1999;

Williams et al., 1995).

Although no precise cut-off point defines the difference between literacy and illiteracy, the commonly accepted working definition of what is meant by literate is the ability to write and to read, understand, and interpret information written at the eighth-grade level or above. On the other end of the continuum, illiterate is defined as being unable to read or write at all or having reading and writing skills at the fourth-grade level or below.

Low literacy, also termed

marginally literate or

marginally illiterate, refers to the ability of adults to read, write, and comprehend information between the fifth- and eighth-grade levels of difficulty. Persons with low literacy have trouble using commonly printed and written information to meet their everyday needs, such as reading a TV schedule, taking a telephone message, or filling out a relatively simple application form (

Doak et al., 1996).

Functional illiteracy means that adults lack the fundamental reading, writing, and comprehension skills that are needed to operate effectively in today’s society. People who are functionally illiterate have very limited competency to perform the tasks of everyday life (

Giorgianni, 1998). They do not read well enough to understand and interpret what they have read or use the information as it was intended (

Doak et al., 1996). For example, someone who is functionally illiterate may be able to read the simple words on a label of a can of soup that directs them to “Pour soup into pan. Add one can water. Heat until hot.” However, they cannot comprehend the meaning and sequence of the words to carry through with these directions.

Conventional grade-level definitions of literacy are considered conservative because even an adult with the ability to read at the eighth-grade level will encounter difficulties in functioning in today’s advanced society. However, although an individual may have poor reading skills, this does not necessarily imply a lack of intelligence. Low literacy or illiteracy cannot be equated with IQ level. A person can be illiterate or low literate, yet intellectually be within at least normal IQ range (

Doak et al., 1996).

Health literacy is defined by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, Title V, as the “degree to which an individual has the capacity to obtain, communicate, process, and understand basic health information and services to make appropriate health decisions” (

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2011, para 1). Health literacy requires a person to do more than simply read patient education materials or make an appointment. A health-literate individual must, for example, be able to read a medication label and then compute the correct dose and frequency of taking the medication. He or she must be able to fill out lengthy health insurance forms, know when to vaccinate his or her child or have a mammogram, or give informed consent for a lifesaving procedure. Although literacy and health literacy are closely related, they are different concepts. Health literacy is complex, such that even those people with strong reading and writing skills, high levels of education, and affluence can face challenges with health literacy. In fact, 45% of high school graduates have limited health literacy skills (

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010).

The CDC (2011) outlines the following common health literacy challenges facing many people:

1. They are not familiar with medical terms or how their bodies work.

2. They have to interpret or calculate numbers or risks that could have health and safety consequences.

3. They are scared and confused when diagnosed with a serious illness.

4. They have health conditions that require high levels of complicated self-care instructions.

5. They are voting on a critical local issue affecting the community’s health and are relying on unfamiliar technical information.

Due to multiple factors, health literacy level cannot be determined from stereotypes, generalizations, or assumptions, or by simply looking at a patient. Furthermore, health literacy levels change over time with education, aging, social interactions, language, culture, and life experiences with health and disease (

Speros, 2011). The Ad Hoc Committee on Health Literacy for the Council on Scientific Affairs of the American Medical Association (1999) concluded that an individual’s functional health literacy is likely to be significantly worse than his or her general literacy skills because of the complicated language (medicalese) used in the healthcare field.

Health literacy is a complex issue, and many variables have the potential to influence an individual’s capacity to obtain, process, and understand information. Some have suggested that “if health literacy is the ability to function in the health care environment, it must be dependent upon the characteristics of both the individual and the health care system” (

Baker, 2006, p. 878). Health literacy should be considered context specific and, as such, is influenced by the client, the complexity of the condition and treatment, and the environment in which the treatment takes place (

Volandes, 2007).

With the widespread adoption of the managed care model and the Affordable Care Act, both of which require individuals to take more responsibility for self-care and symptom management, health literacy is becoming an important determinant of health status. Poor health literacy may lead to serious negative consequences, such as increased morbidity and mortality, when a person is unable to read and comprehend instructions for medications, follow-up appointments, diet, procedures, and other regimens. Patients cannot be expected to be compliant, autonomous, and self-directed in navigating the healthcare system if they do not have the ability to follow basic instructions (

Bennett, Chen, Soroui, & White, 2009;

Davis et al., 2006). Further, low health literacy can result in more emergency department visits and hospital admissions, with the elderly experiencing lower health status with increased mortality. It also affects use of preventive services such as mammography and flu vaccination, and lessens the likelihood a person will take medications or follow health instructions correctly (

Berkman, Sheridan, Donahue, Halpern, & Crotty, 2011).

Reading,

readability, and

comprehension also are terms frequently used when determining levels of literacy.

Fisher (1999) defines

reading or word recognition as “the process of transforming letters into words and being able to pronounce them correctly” (p. 57). Word recognition test scores, which can be misleading because they indicate only a person’s ability to identify words, not understand them, are usually three grade levels higher than comprehension scores (

Fisher, 1999).

Hirsch (2001) addresses the public’s confusion between reading in the sense of being able to decode words fluently and reading in the sense of being able to comprehend the meaning of words.

Readability is defined as the ease with which written or printed information can be read. It is based on a measure of several different elements within a given text of printed material, such as the level of language being used and the layout and design of the page (

Hasselkus, 2009). These variables influence with what degree of success a group of readers will be able to read the style of writing of a selected printed passage.

Comprehension, in comparison, is the degree to which individuals understand what they have read (

Fisher, 1999;

Koo, Krass, & Aslani, 2005). It is the ability to grasp the meaning of a message—to get the gist of it. A healthcare professional can determine whether comprehension of health instruction has occurred by noting whether clients are able to demonstrate correctly or recall in their own words the message that was received.

The ability to read does not, by itself, guarantee reading comprehension. Comprehension is affected by the amount, clarity, and complexity of the information presented. If the elements of logic, language, and experience in health instruction are compatible with and culturally appropriate to the clients’ background, the message likely will be clear and relevant to them (

Doak et al., 1996). Conversely, a mismatch will likely make the message confusing, incomprehensible, and useless to the individual.

Illness, medication, treatment, or disruptive life situations, all of which may cause stress and anxiety, have been found to interfere significantly with comprehension. The ability to take in medical information, store it in memory, and recall it when necessary is affected by many other factors as well, such as the length of time between information disclosure and the need to remember the information, the nature of the information (how threatening), and the method of presentation (

Doak et al., 1996;

Doak, Doak, Friedell, & Meade, 1998;

Kessels, 2003;

Ley, 1979).

Readability and comprehension, therefore, are particularly complex activities involving many variables with respect to both the reader and the actual written material (

Doak et al., 1996;

Fisher, 1999). Both are commonly determined by using one or more measurement formulas (see the later discussions of measurement tools in this chapter).

Table 7-2 shows examples of elements that affect readability and comprehension.

Literacy Relative to Oral Instruction

To date, very little attention has been paid to the role of oral communication in the assessment of illiteracy. Certainly, inability to comprehend the spoken word or oral instruction above the level of understanding simple words, phrases, and slang words should be considered an important element in the definition or assessment of literacy. Most health information can be provided verbally, and many clients prefer to learn in a face-to-face encounter (

Morrow et al., 2007). However, oral instruction alone is not a very successful method of teaching. “Written information is better remembered and leads to better treatment adherence” (

Kessels, 2003, p. 221).

Doak, Doak, and Root (1985) address the fact that there is no universally accepted way to test the degree of difficulty with oral language. However, as these authors observe, “It is believed that some of the same characteristics that are critical for written materials will also affect the comprehensibility of spoken language” (p. 40). Much more research needs to be done on “iloralacy,” or the inability to understand simple oral language, as a generic concept of illiteracy (

Hirsch, 2001;

Zarcadoolas et al., 2006).

Literacy Relative to Computer Instruction

The literacy issue has traditionally been examined from the standpoint of readability and comprehension of printed materials. More recently, computer literacy has emerged as an increasingly popular concern and an important dimension of the literacy issue. To an ever greater extent, educators and consumers are relying on computers as educational tools, and the potential of this technology is transforming the way healthcare information is accessed and shared. Clients who are well educated and career oriented are likely to own a computer and be computer literate, whereas those with limited resources, literacy skills, and technological know-how are being left behind (

Kerka, 2003;

Zarcadoolas et al., 2006).

As healthcare organizations and agencies continue to invest more resources in computer technology and software programs for educational purposes, computer literacy in the overall client population must be addressed. Computers not only are used to convey instructional messages, but they also serve as valuable tools for accessing a wide array of additional sources of health information.

The opportunity to expand clients’ knowledge base through telecommunications and virtual resources requires nurse educators to attend to computer literacy levels of their audiences. In the same way that they now recognize the negative effects that illiteracy and low literacy have had in restricting the information base of consumers of health care when printed materials are relied upon, nurses must begin to advocate for computer literacy in the public they serve (

Doak et al., 1996;

Moore, Bias, Prentice, Fletcher, & Vaughn, 2009). Computer software programs can be made suitable for use by low-literate learners as long as these individuals have the basic capacity to access and operate computers and the information is simplified for readability and comprehension.

Since 2000, the concept of e-health and informatics has grown globally to encompass use of the Internet and other virtual resources for the delivery of patient education and organization of care (

Pagliari et al., 2005). This innovative approach requires that patients have additional skills to communicate with healthcare providers and understand their treatment plan. Thus

e-health literacy must be an additional concern to the nurse.

Norman and Skinner (2006a) define e-health literacy as “the ability to seek, find, understand, and appraise health information from electronic sources and apply the knowledge gained to addressing or solving a health problem” (para 6). These authors draw attention to the knowledge and complex skill set that is often taken for granted when people interact with technology to access and share information. Nurses now must focus their attention on learning and usability issues, whether it be in an acute care setting or at the population health level. E-health tools include digital resources designed to help patients, consumers, and caregivers find health information, store and manage their personal health information, make decisions, and manage their health (CDC, 2009).

The use of e-health tools and interventions by healthcare professionals and patients in the future appears to hold promise for increasing transparency and expanding both parties’ knowledge base. Similar to health literacy, however, e-health literacy levels are complex and can change based on technological advances. Therefore, undertaking an assessment of not only health literacy but also e-health literacy is an important action the nurse can take to determine whether the use of technology will be useful or detrimental to the client’s understanding of health information (

Collins, Currie, Bakken, Vawdrey, & Stone, 2012).

SCOPE AND INCIDENCE OF THE PROBLEM

Literacy has been termed the “silent epidemic,” the “silent barrier,” the “silent disability,” and “the dirty little secret” (

Conlin & Schumann, 2002;

Doak & Doak, 1987;

Kefalides, 1999;

Wedgeworth, 2007). Based on available statistics over the past 20 years, it is clear that the United States has significant literacy problems. In fact, this country ranked only among the middle of industrialized nations on most measures of adult literacy—yet many of its educators, elected representatives, and social advocates have remained blind to this significant problem (

Kogut, 2004).

In 1985, the U.S. Department of Education undertook the first national assessment of adult literacy, known as the Young Adult Literacy Survey. Since then, the federal government has conducted two subsequent large-scale assessments (

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2003).

The 1992 NALS, considered to be a highly accurate and detailed profile on the condition of English-language literacy in the United States, revealed surprising statistics. NALS researchers interviewed and collected data from a representative sample of 26,000 individuals, age 16 years and older. Based on the findings from an assessment of literacy skills in three areas (prose, document, and quantitative), literacy abilities were categorized into five levels, with Level 1being the lowest and Level 5 being the highest.

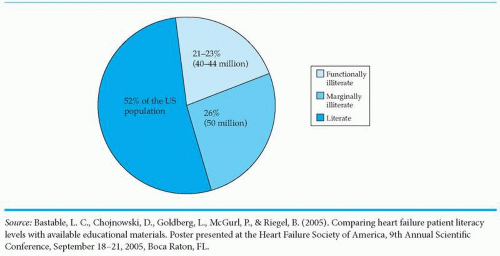

Some 21% to 23% (approximately 40-44 million) of the 191 million adults in the country at that time scored in the lowest level of the three skill areas. They were considered to be functionally illiterate. Another 25% to 28%, or approximately 50 million adults, scored in the Level 2 category; that is, they were considered to have low literacy skills. Thus the number of illiterate and low-literate adults in the United States conservatively was estimated to be approximately 90-94 million in total (

Figure 7-1).

This figure indicates that roughly half of the U.S. adult population had deficiencies in reading, writing, and math skills (

Fisher, 1999;

Weiss, 2003). The researchers found that those individuals with poor literacy skills (Levels 1 and 2) were disproportionately more often from minority populations, from lower socioeconomic groups, and had poorer health status (

Andrus & Roth, 2002;

Fisher, 1999;

Weiss, 2003).

In 2003, building on the NALS of 10 years earlier, the National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL) became the first study to identify the literacy of America’s adults in the 21st century. New, more sensitive instruments were designed to enhance measurement of the literacy abilities of the least-literate adults. Most important, this evaluation included a health literacy component to assess adults’ understanding of health-related materials and forms (

National Center for Education Statistics, 2006).

The NAAL categorized literacy skills into four levels, and the findings revealed the following percentages and total numbers: below basic, 14% (30 million); basic, 29% (63 million); intermediate, 44% (95 million); and proficient, 13% (28 million). Of the overall 216 million adults in the U.S. population in 2003, 43% (93 million) fell into the lowest two categories (

National Center for Education Statistics, 2006).

The average score results indicated no signi ficant change in prose and document literacy and only a slight increase in quantitative literacy between 1992 and 2003. However, a higher proportionate percentage of several population groups, such as those who did not graduate from high school, Hispanics, and those older than 65 years of age, fell into the below basic level of prose literacy (

Kutner, Greenberg, Jin, & Paulsen, 2006). The NAAL’s Health Literacy Report specifically found that 36% (47 million) of adults had basic or below basic health literacy and that older adults (65 years and older) had the lowest health literacy levels (

Baer, Kunter, & Sabatini, 2009;

National Center for Education Statistics, 2006). For more detailed information on the NAAL survey, visit the National Center for Education Statistics at http://www.nces.ed.gov/naal.

In 2004, the Institute of Medicine (IOM), the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), and the American Medical Association (AMA) issued their own reports on the status of health literacy in the United States. All three reports revealed that as many as 50% of all American adults lack the basic reading and numerical skills essential to function adequately in the healthcare environment (

Aldridge, 2004; IOM, 2004;

Schwartzberg et al., 2004;

Weiss et al., 2005).

Table 7-3 lists websites that provide even more information on health literacy.

Limited literacy leads to poor health outcomes. In fact, literacy skills are “a stronger predictor of an individual’s health status than income, employment status, education level, and racial or ethnic group” (

Weiss, 2007, p. 13). Individuals with limited literacy skills are less knowledgeable about their health problems and have higher hospitalization rates, more emergency department visits, higher healthcare costs, less healthy behaviors, and poorer health status (

Weiss, 2007;

Weiss et al., 2005). The American College of Physicians Foundation has created a short video that includes interviews with actual patients to illustrate the consequences of limited reading and health literacy. To view this video and others, see

Table 7-4.

Thus, according to the findings of the NALS and NAAL reports, 4 to 5 out of every 10 Americans lack the basic reading and comprehension skills to perform simple, everyday literacy tasks (

National Center for Education Statistics, 2006). Because the mean reading level of the U.S. population is at or below the eighth-grade level and many people read two to four grades below their reported level of formal education achieved, millions are challenged by the demands of common, day-today activities (

Winslow, 2001). For example,

a person needs to be able to read at the 6th-grade level to understand a driver’s license manual, at the 8th-grade level to follow directions on a frozen dinner package, and at the 10th-grade level to read instructions on a bottle of aspirin (

Doak et al., 1985). The literacy problem is so widespread that the U.S. government, in an efiort to reduce traffic accidents, has replaced some conventional printed road signs with road signs using symbols (

Loughrey, 1983).

Because of the difficulty inherent in defining and testing literacy, the lack of inclusion of unidenti fied illegal immigrants in the sample populations studied, and the fact that few people with limited reading skills admit to having any difficulty, the scope of the literacy problem is thought to be much greater than the estimates found in formal studies (

Brownson, 1998;

Doak et al., 1996;

Weiss, 2003).

The rates of illiteracy and low literacy in general and health literacy in particular continue to pose a major threat to many segments of society. This problem is expected to grow worse in light of the many forces operating in the United States and worldwide unless specific measures are taken to curb the tide. To be literate 100 years ago meant that people could read and write their own name. Today, being literate means that one is able to learn new skills, think critically, problem solve, and apply general knowledge to various situations (

Weiss, 2003).

TRENDS ASSOCIATED WITH LITERACY PROBLEMS

An increase in the number of immigrants with English as a second language

The aging of the population

The increasing amount and complexity of information

The increasing sophistication of technology

More people living in poverty

Changes in policies and funding for public education

Disparities between minority versus nonminority populations

All of these factors correlate significantly with the level of formal schooling attained and the level of literacy ability. Although research indicates that the number of years of schooling is not a good predictor of literacy level, there remains some correlation between a person’s educational background and the ability to read. As society becomes increasingly more technologically challenging, with new products to use and more complicated functions to perform, the basic language requirements needed for survival continue to expand. Many more people are beginning to fall behind, unable to keep up with an ever more sophisticated world.

In cases of both illiteracy and low literacy, the level of readability is measured in terms of performance, not years of school attendance. The mean literacy level of the U.S. population is at or below eighth grade. Medicaid enrollees, on average, read at the fifth-grade level (

Andrus & Roth, 2002;

Giorgianni, 1998;

Winslow, 2001). Many people read at least two to four grade levels below their reported level of formal education. For those in poverty, the gap between grade level completed and actual reading level is even greater (

Andrus & Roth, 2002). This deficiency persists because schools have a tendency to promote students for social and age-related reasons rather than for academic achievement alone (

Feldman, 1997), because clients may report inaccurate histories of years of school attended, and because reading skills may be lost over time through lack of practice (

Davidhizar & Brownson, 1999;

Miller & Bodie, 1994;

Weiss, 2003;

Williams et al., 2002).

Levels of literacy are often seen as indicators of the well-being of individuals, and the literacy problem has larger implications for the social and economic status of the country as a whole (

Kogut, 2004). Low levels of literacy have been associated with marginal productivity, high unemployment, minimum earnings, high costs of health care, and high rates of welfare dependency (

Andrus & Roth, 2002;

Giorgianni, 1998;

Winslow, 2001;

Ziegler, 1998).

In addition, illiteracy contributes to many of the grave social issues confronting the United States today, such as homelessness, teen pregnancy, unemployment, delinquency, crime, and drug abuse (

Fleener & Scholl, 1992;

Kogut, 2004). Deficiencies in basic literacy skills become compounded and create devastating cumulative effects on individuals, which produces a social burden that is extremely costly for the American people. Illiteracy and low literacy are not necessarily the reasons for these ills, but the high correlation between literacy levels and social problems is a marker for disconnectedness from society in general (

Kogut, 2004;

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2003).

THOSE AT RISK

Illiteracy has been described “as an invisible handicap that affects all classes, ethnic groups, and ages” (

Fleener & Scholl, 1992, p. 740). It is a silent disability. Illiteracy knows no boundaries and exists among persons of every race and ethnic background, socioeconomic class, and age category (

Duffy & Snyder, 1999;

Weiss, 2003). It is true, however, that illiteracy is rare in the higher socioeconomic classes, for example, and that certain segments of the U.S. population are more likely to be affected than others by lack of literacy skills.

According to recent research (

Cole, 2000;

Hayes, 2000;

Kogut, 2004;

Montalto & Spiegler, 2001;

Nath, Sylvester, Yasek, & Gunel, 2001;

Rothman et al., 2004;

Schillinger et al., 2002;

Schultz, 2002;

Weiss, 2007;

Williams, Baker, Parker, & Nurss, 1998;

Winslow, 2001;

Wood, 2005), populations that have been identified as having poorer reading and comprehension skills than the average American include the following:

Those who are economically disadvantaged

Older adults

Immigrants (particularly illegal ones)

Those with English as a second language

Racial minorities

High school dropouts

Those who are unemployed

Prisoners

Inner-city and rural residents

Those with poor health status resulting from chronic mental and physical problems

Those on Medicaid

Of course, not every member of an at-risk population suffers from low literacy. Further, some people do not fall into an “at risk” category, yet still lack literacy skills (

Baur, 2011;

Weiss, 2007).

With respect to demographics, statistics indicate that 34 million Americans are presently living in poverty and that nearly half (43%) of all adults with low literacy live in poverty (

Darling, 2004). Although those who are disadvantaged represent many diverse cultural and ethnic groups, including millions of poor White people, one third of disadvantaged people in this country are minorities, and a larger percentage of minorities fall into the disadvantaged category (

Giorgianni, 1998;

Weiss et al., 2005).

In this 21st century, the major growth in the U.S. population is predicted to come from the ranks of minority groups. By 2050, 53% of the people in the United States are projected to belong to a racial or ethnic minority and one in five will be foreign born (

Passel & Cohn, 2008). The U.S. Bureau of the Census reported that almost 40 million immigrants reside in this country, more than quadruple the number in 1970, with more than half of those individuals living in California, New York, Florida, and Texas. One third of the foreign-born population has arrived since 2000, 62% of immigrant families have children, and 30% of immigrants do not have a high school diploma (

Grieco et al., 2012;

U.S. Census Bureau, 2012). Of the 1100 community-based

adult literacy programs supported by ProLiteracy, 86% teach English as a second language (ESL) (M. Diecuch, personal communication, August 14, 2012). Nurse educators must recognize how these demographic changes will affect the way in which services need to be rendered, educational materials need to be developed, and information needs to be marketed (

Andrus & Roth, 2002;

Borrayo, 2004;

Nurss et al., 1997;

Robinson, 2000).

Many minority and economically disadvantaged people, as well as the prison population—which has the highest concentration of adult illiteracy (

Duffy & Snyder, 1999)—are not bene ficiaries of mainstream health education activities, which often fail to reach them. Overall, they are not active seekers of health information because they tend to have weaker communication skills and inadequate foundational knowledge on which to better understand their needs. Many lack enough fluency to make good use of written health education materials. Moreover, while the majority of PEMs are written in English, fluency in verbal skills in another language does not guarantee functional literacy in that native language (

Horner, Surratt, & Juliusson, 2000). Areas with the highest percentage of minorities and high rates of poverty and immigration also have the highest percentage of functionally illiterate people. When these people need medical care, they tend to require more resources, have longer hospital stays, and have a greater number of readmissions (

Weiss, 2007). The challenge now and in the future will be to find improved ways of communicating with these population groups and to develop innovative strategies in the delivery of health care to them.

Among Americans older than 65 years of age, two out of five adults (approximately 40%) are considered functionally illiterate (

Davidhizar & Brownson, 1999;

Gazmararian et al., 1999;

Williams et al., 2002). In 2010, the population of older adults totaled approximately 40 million (more than 13% of the total U.S. population), and individuals older than 85 years of age make up the fastest-growing age group in the country. At the turn of the century, the “oldest-old” numbered 4.2 million people, but it is projected that by 2050 that number could reach 19 million. Children born today can expect to live to an average age of at least 80 years. Statistics indicate that the U.S. population is growing older as people live longer. By 2030, it is expected that the 65-and-older population will double from its size at the beginning of the 21st century (

Crandell, Crandell, & Vander Zanden, 2012;

Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics, 2012).

As time goes on, members of the older population will be more educated and demand more services. In 1960, only 20% of older people were high school graduates; in 2010, 75% were educated at the high school level (

Greenberg, 2011). Although these statistical trends indicate the U.S. population will include a more highly educated group of older adults in the future, the information explosion and rapid technological advances may cause them to fall behind relative to future standards of education. Today, the illiteracy problem in the aged is caused by the facts that not only did these individuals have less education in the past, but their reading skills have also declined over time because of disuse. If a person does not use a skill, he or she loses that skill. Reading ability can deteriorate over time if not exercised regularly (

Brownson, 1998).

In addition, cognition and some types of intellectual functioning are affected by aging (

Crandell et al., 2012;

Kessels, 2003;

Santrock, 2011). The vast majority of older people have some degree of cognitive changes and sensory impairments, such as vision and hearing loss. On the average, 28% of people age 65 and 38% of those older than 75 years of age have serious hearing impairment; women fare better than men in this regard (

Crandell et al., 2012). Along with these normal physiological changes, many older adults suffer from chronic diseases, and large numbers are taking prescribed

medications. All of these conditions can interfere with the ability to learn or can negatively affect thought processes, which contributes to the high incidence of illiteracy in this population group.

Beyond the issue of prevalence, illiteracy presents unique psychosocial problems for the older adult. Because older persons tend to process information more slowly than do young adults, they may become more easily frustrated in a learning situation (

Crandell et al., 2012;

Kessels, 2003). Furthermore, many older individuals have developed ways to compensate for missing skills through their support network. Lifetime patterns of behavior have been set, such that they may now lack the motivation to improve their literacy skills. Today and in the years to come, those nurses involved with providing health education will be challenged to overcome these obstacles to learning in the older adult.

Cultural diversity, although not considered to be directly related to illiteracy, may also serve as a barrier to effective client education. According to

Davidhizar and Brownson (1999)—and a contention backed up by the NAAL’s 2003 statistics—most adults with illiteracy problems in the United States are White, native-born, English-speaking individuals. However, when examining the proportion of the population that has poor literacy skills, minority ethnic groups are at a disproportionately higher risk (

Andrus & Roth, 2002).

When healthcare providers communicate with clients from cultures different from their own, it is important for them to be aware that their clients may not be fluent in English. Furthermore, even if people speak the English language, the meanings of words and their understanding of facts may vary significantly based on life experiences, family background, and culture of origin, especially if English is the client’s second language (

Purnell, 2013). In conversation, an individual must be able to understand undertones, voice intonations, and the context (slang, terminology, or customs) in which the message is being delivered.

Purnell (2013) stress the importance of assessing other elements of verbal and nonverbal communication, such as emotional tone of speech, gestures, eye contact, touch, voice volume, and stance, between persons of different cultures that may affect the interpretation of behavior and the validation of information received or sent. Educators must be aware of these potential barriers to communication when interacting with clients from other cultures whose literacy skills may be limited. Given the increasing diversity of the U.S. population, most currently available written materials are considered inadequate based on the literacy level of minority groups and the fact that the majority of PEMs are available only in English.

Thus individuals with less education, whose number often includes low-income persons, older adults, racial minorities, and people for whom English is a second language, are likely to have more difficulty with reading and comprehending written materials as well as with understanding oral instruction (

Winslow, 2001). This profile is not intended to stereotype people who are illiterate, but rather to give a broad picture of who most likely lacks literacy skills. When carrying out assessments on their patient populations, it is essential that nurses and other healthcare providers be aware of those susceptible to having literacy problems.