Types of Objectives

Characteristics of Goals and Objectives

The Debate About Using Behavioral Objectives

Writing Behavioral Objectives and Goals

Performance Words with Many or Few Interpretations

Common Mistakes When Writing Objectives

Taxonomy of Objectives According to Learning Domains

The Cognitive Domain

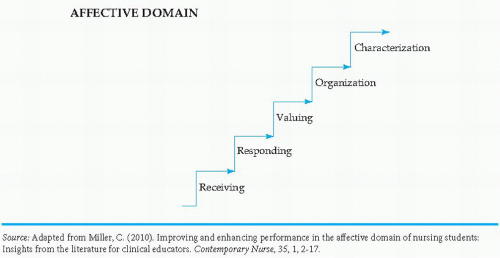

The Affective Domain

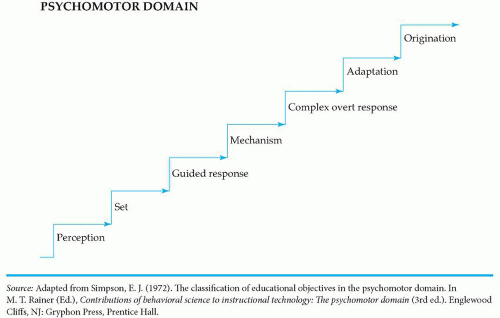

The Psychomotor Domain

Development of Teaching Plans

Use of Learning Contracts

Components of the Learning Contract

Steps to Implement the Learning Contract

The Concept of Learning Curve

State of the Evidence

Identify the differences between goals and objectives.

Recognize opposing viewpoints regarding the use of behavioral objectives in education.

Demonstrate the ability to write behavioral objectives accurately and concisely using the four components of condition, performance, criterion, and who will do the performing.

Cite the errors most frequently made in writing objectives.

Distinguish among the three domains of learning.

Explain the instructional methods appropriate for teaching in the cognitive, affective, and psychomotor domains.

Develop teaching plans that reflect internal consistency between elements.

Recognize the role of the nurse educator in formulating objectives for the planning, implementation, and evaluation of teaching and learning.

Describe the importance of learning contracts as an alternative approach to structuring a learning experience.

Identify the potential application of the learning curve concept to the development of psychomotor skills.

and complexity—pertains to the nature of the knowledge to be learned, the behaviors most relevant and attainable for a particular learner or group of learners, and the sequencing of knowledge and experiences for learning.

a series of teaching sessions. According to Mager (1997), an objective describes a performance that learners should be able to exhibit before they are considered competent. A behavioral objective is the intended result of instruction, not the process or means of instruction itself. Objectives are statements of specific, short-term behaviors that lead step by step to the more general, overall long-term goal.

a goal that a patient will maintain a salt-free diet is likely to be impossible to accomplish or to adhere to over an extended period of time. Establishing a goal of maintaining a low-salt diet, with the objectives of learning to avoid eating and preparing high-sodium foods, is a much more realistic and achievable expectation of the learner.

The understanding by experienced educators of learners’ needs is so sophisticated that the exercise of writing behavioral objectives is superfluous.

The practice of writing specific behavioral objectives leads to reductionism, a format that reduces behavioral processes into equivalents that do not reflect the sum total of the parts.

Objective writing is a time-consuming task, requiring more effort for development than is warranted by their effect on an instructional program. That is, the cost-benefit ratio does not justify the amount of time required to formulate objectives.

The preparation of objectives is merely a pedagogic exercise often expressing the teacher’s expectations of the outcome of teaching and precluding the opportunity for learners to seek their own objectives.

Predetermined objectives, with their emphasis on precise and observable learner behaviors, force teachers and learners to attend only to specific areas, which stifles creativity and interferes with the freedom to learn and to teach.

The writing of specific objectives is incompatible with the many complex fields of study such as nursing because an infinite number of objectives are possible for almost any subject or topic.

Behavioral objectives are unable to capture the more intricate cognitive processes that are not readily observable and measurable.

Helps to keep educators’ thinking on target and learner centered.

Communicates to others—both learners and healthcare team members alike—what is planned for teaching and learning.

Helps learners understand what is expected of them so that they can keep track of their progress.

Forces the educator to organize educational materials so as not to get lost in content and forget the learner’s role in the process.

Encourages educators to question their own motives—to think deliberately about why they are doing things and analyze which positive results will be attained from accomplishing specific objectives.

Tailors teaching to the learner’s particular circumstances and needs.

Creates guideposts for teacher evaluation and documentation of success or failure.

Focuses attention not on what is taught but on what the learner will come away with once the teaching-learning process is completed.

Orients both teacher and learner to the specific end results of instruction.

Makes it easier for the learner to visualize performing the required actions.

How will anyone else know which objectives have been set?

How will the educator evaluate and document success or failure?

How will learners keep track of their progress?

The time that will be needed for teaching and learning

The clues as to how the learner best acquires information

The teaching methods that will work most effectively

The best ways to evaluate the learner’s progress

TABLE 10-1 The Four-Part Method of Objective Writing | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

for the learning of particular skill sets by patients and their significant others.

TABLE 10-2 Samples of Written Objectives | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TABLE 10-3 Verbals with Many or Few Interpretations | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

and, on the other hand, are specific and relatively easy to measure (Gronlund, 1985; Gronlund & Brookhart, 2008).

Describing what the instructor rather than the learner is expected to do

Including more than one expected behavior in a single objective (avoid using the compound word and to connect two verbs—e.g., the learner will select and prepare)

Forgetting to identify all four components of condition, performance, criterion, and the learner

Using terms for performance that are subject to many interpretations, not action oriented, and difficult to measure

Writing objectives that are unattainable given the ability level of the learner

Writing objectives that do not relate to the stated goal

Cluttering objectives by including unnecessary information

Being too general so as not to specify clearly the expected behavior to be achieved

TABLE 10-4 Writing SMART Objectives | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

a very useful taxonomy, known as the taxonomy of educational objectives, as a tool for systematically and logically classifying behavioral objectives. This taxonomy, which became widely accepted as a standard aid for planning as well as evaluating learning, is divided into three broad categories or domains—cognitive, affective, and psychomotor.

TABLE 10-5 Levels of Cognitive Behavior | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TABLE 10-6 Commonly Used Verbs According to Domain Classification | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

instructional methods used primarily for affective and psychomotor learning. Cognitive knowledge, however, is an essential prerequisite for the learner to engage in other educational activities such as group discussion or role playing. Otherwise, what results is pooled ignorance. For example, clients cannot adequately learn through group discussion if they do not possess an accurate and at least basic knowledge level of the subject at hand to draw on for purposes of discourse. Participating in a group discussion experience, in turn, is not the same thing as engaging in a brainstorming session. Brainstorming does not necessarily require prior knowledge of information about issues or problems to be explored.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree