Leininger’s Theory of Culture Care Diversity and Universality in Nursing Practice

Marilyn R. McFarland∗

Nursing is a learned, humanistic, and scientific profession and discipline focused on human care phenomena and caring activities in order to assist, support, facilitate or enable individuals or groups to maintain or regain their health or wellbeing in culturally meaningful and beneficial ways, or help individuals face handicaps or death.

History and Background

Nurse anthropologist Madeleine Leininger developed the culture care theory and ethnonursing research method to help researchers study transcultural human care phenomena and discover the knowledge nurses need to provide care in an increasingly multicultural world (2002a,b, 2006). In the late 1950s she envisioned that the world was becoming one in which humans interact on a global level. She realized that she needed to go beyond anthropology with its emphasis on groups of people in different parts of the world to express her thoughts from a nursing perspective. At that time nursing practice was based on the medical model and nurses practiced primarily in hospitals or public health departments. Leininger had a holistic view of nursing that incorporated some anthropological concepts but also a strong nursing component—a vision for nursing that would focus on human beings in a multicultural world. Leininger (1995a) stated, “I envisioned that transcultural nursing was different from anthropology in that the focus was oncomparative health care, health, and well-being in different environmental contexts and cultures” (p. 26). Her vision addressed a deficiency in health care—the absence of cultural knowledge.

From the beginning, the language of culture and care was foundational to transcultural nursing. Before Leininger founded the field of transcultural nursing she believed that care was the most important component of nursing. She stated, “Care is the essence and the central, unifying, and dominant domain to characterize nursing” (Leininger, 1984, p. 3). She blended culture from anthropology and care from nursing and postulated that “human caring is a universal phenomenon, but the expressions, processes, and patterns vary among cultures” (Leininger, 1984, p. 5). For example, Leininger referred to culture-specific care and culturally congruent care as integral parts of the theory. The sunrise (model) enabler—based on the theory—is used as a guide for research on culture and care and for culturally congruent nursing care practice. The first transcultural nursing research was Leininger’s own study of the Gadsup people in Papua, New Guinea, in the early 1960s. In 1965 the first formal courses and doctoral program in transcultural nursing were established by Leininger at University of Colorado School of Nursing. The first book published on the culture care theory was Leininger’s (1970) Nursing and Anthropology: Two Worlds to Blend. Leininger and McFarland (2002) co-authored the third edition update to Transcultural Nursing: Concepts, Theories, Research, and Practices (1995b), and in 2006 they published the second edition of her theory book titled Culture Care Diversity & Universality: A Worldwide Nursing Theory.

In 1974, Dr. Leininger founded the Transcultural Nursing Society to serve nurses worldwide with its mission “to enhance the quality of culturally congruent, competent, and equitable care that results in improved health and well-being for people worldwide” (www.tcns.org). The society holds an annual international conference during which transcultural research studies from around the globe are presented. The Journal of Transcultural Nursing was first published in 1989 as the official journal of the society. In 1988 certification of transcultural nurses (CTN) was initiated and revised in 2010 (Pacquiao & McNeal) to encompass a basic (CTN-B) level and an advanced (CTN-A) level. With the growing emphasis on globalization and cultural competence, Leininger’s work gains added meaning and significance. Contemporary Nurse Journal has published the special issues of Advances in Contemporary Transcultural Nursing in 2003 and 2008 with practice applications and reviews of studies guided by the culture care theory conducted by nurse researchers from around the world.

Leininger (2002a,b, 2006, 2007, 2011) continued throughout her life to clarify the essential features of culture care diversity and universality theory within the context of transcultural nursing.

Transcultural nursing is a substantive area of study and practice focused on comparative human care (caring) differences and similarities of the beliefs, values, and practices of individuals or groups of similar or different cultures. Transcultural nursing’s goal is to provide culture-specific and universal nursing care practices for the health and well-being of people or to help them face unfavorable human conditions, illness, or death in culturally meaningful ways (Leininger, 2002a, p. 46).

Dr. Leininger’s most recent work on the culture care theory has been through published work in peer-reviewed professional journals. She co-authored an interview piece in Nursing Science Quarterly (Clarke, McFarland, Andrews, et al., 2009) in which she discussed the history and future of transcultural care, the nursing profession, and global health care. In 2011, she authored a reflective article in the Online Journal of Cultural Competence in Nursing and Healthcare. She studied three Western and one non-Western culture (Old Order Amish Americans, Anglo Americans, Mexican-Americans, and the Gadsup of the Eastern Highlands of New Guinea) in order to obtain in-depth knowledge about father protective care beliefs and practices with the goal of using that knowledge to provide culturally congruent care. Leininger (2011) reported that culture care repatterning and/or restructuring actions and decisions were very difficult for fathers in the four cultural groups to consider as they wanted to preserve their cultures and traditional care practices. However, all groups reported that some members embraced modern technologies but feared harm from their use. Leininger began work on a new culture care construct, collaborative care, which she co-presented with Marilyn McFarland via a keynote videocast at the 37th Annual Conference of Transcultural Nursing Society in October 2011 and accepted for publication in the Online Journal of Cultural Competence in Healthcare.

Dr. Madeleine Leininger died peacefully on August 10, 2012, in Omaha, Nebraska. She continued to work until shortly before her passing, collaborating with colleagues on contributions to several projects and publications in progress including revisions to her website (www.madeleine-leininger.com/en/index.shtml) and updates to future editions of her books. Her legacy is the theory of culture care diversity and universality and transcultural nursing that continues to inspire those whom she mentored, taught, and influenced throughout her accomplished career.

Overview of Leininger’s Culture Care Theory

The construct of culture in Leininger’s theory borrows its meaning from anthropology. Culture is the “learned, shared, and transmitted knowledge of values, beliefs, norms, and lifeways of a particular group that are generally transmitted intergenerationally and influence thinking, decisions, and actions in patterned or certain ways” (Leininger, 2002a, p. 47). Culture can be discovered in the actions, practices, language, norms or rules for behavior (values and beliefs), and in the symbols that are important to the people. As Leininger has stated, culture is learned and then passed down from generation to generation.

The most significant effect of Leininger’s theory has been on the construct of caring in relation to nursing practice (Clarke, et al., 2009, p. 234). The goal of the culture care theory (CCT) is to provide culturally congruent nursing care, which refers to “culturally based care knowledge, acts, and decisions used in sensitive and knowledgeable ways to appropriately and meaningfully fit the cultural values, beliefs, and lifeways of clients for their health and wellbeing, or to prevent illness, disabilities, or death” (Leininger, 2006, p. 15). As a companion to her theory Leininger developed enablers to guide nurses in gathering relevant assessment data or conducting a culturalogical assessment. The culturalogical assessment consists of a comprehensiveholistic overview of the client’s background including communication and language, gender and interpersonal relationship customs, appearance, dress, use of space, food preferences, meal preparation, and other lifeways. Leininger’s theory is applicable in the nursing care of clients from racially and ethnically diverse backgrounds as well as the culture care needs of individuals or groups belonging to cultures and subcultures identified on the basis of sexual orientation (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgendered groups); ability or disability (the deaf or hearing impaired or blind or visually impaired); occupation (nursing, medicine, or the military); age (youth, adolescents, elders); or socioeconomic status (poverty or affluence; homelessness).

A key construct of Leininger’s theory is cultural diversity which refers to differences that can be found among and between different cultures. By recognizing variations, the nurse can avoid stereotyping or assuming that all people will respond positively or in the same way to the standards or routines in nursing care. Another construct is that of cultural universality, which refers to the commonalities that exist in different cultures. These ideas led to an important goal of the theory—that is, “to discover similarities and differences about care and its impact on the health and well-being of groups” (Leininger, 1995c, p. 70). Nurses are familiar with professional care, and a construct of generic care is introduced. Generic care or folk care includes remedies passed down from generation to generation within a particular culture. Leininger (1995c) stated, “Interfacing generic and professional care into creative and meaningful nursing may well unlock the essential ingredients for quality healthcare” (p. 81).

Two other constructs of importance in the theory of culture care diversity and universality are culture-specific care and culturally congruent care.

• Culture-specific care refers to care resulting from the identification and abstraction of care practices from a particular culture that lead to the planning and application of nursing care to “fit the specific care needs and life ways” of a client from that culture (Leininger, 1995c, p. 74).

• Culturally congruent care is a major goal of the theory (Leininger, 2006). This refers to “culturally based care knowledge, acts, and decisions used in sensitive and knowledgeable ways to appropriately and meaningfully fit the cultural values, beliefs, and practices of clients for their health and wellbeing, or to prevent illness, disabilities, or death” (p. 15, 2006).

Leininger (2002b) postulated three modes of care actions and decisions for guiding nursing care so nurses in diverse practice settings can provide beneficial and meaningful care that is culturally congruent with the values, beliefs, practices, and worldviews of clients. The three modes of culture care are (a) preservation and/or maintenance; (b) accommodation and/or negotiation; and (c) repatterning and/or restructuring. These modes have substantively influenced the ability of nurses to provide culturally congruent nursing care and thereby fostered the development of culturally competent nurses. Nurses practicing in large urban centers typically care for clients from hundreds of different cultures or subcultures. Leininger’s culture care theory provides practicing nurses with an evidence-based, versatile, useful, and helpful approach to guide them in their daily decisions and actions regardless of the number of clients under their care or complexity of their care needs.

Dr. Leininger developed the ethnonursing research method for nurse researchers to study and advance nursing phenomena from a human science philosophical perspective with the qualitative analytical lens of culture and care (Leininger, 1995 a,b,c; 2002a,b, 2006a; Leininger & McFarland, 2002, 2006). The method was developed with the theory of culture care diversity and universality to study the nursing dimensions of culture care that include care phenomena, research enablers, and the social structural factors (e.g., kinship and social; cultural values, beliefs, and lifeways; religious and philosophical; economic; educational; political/legal systems; technological; and, environmental context, language, and ethnohistory) and three modes of care action and decision (Leininger & McFarland, 2002, 2006; Ray, Morris, & McFarland, 2012).

Recently the ethnonursing method has been proposed for use in other health care disciplines. McFarland, Wehbe-Alamah, Wilson, and colleagues (2011) developed the meta-ethnonursing research method after analyzing and synthesizing 23 dissertations conceptualized with the theory of culture care diversity and universality using the ethnonursing research method. Using the CCT as a guide, culture care action and decision meta-modes were discovered that were focused on providing culturally congruent nursing care among cultural groups (McFarland, Mixer, Wehbe-Alamah, et al., 2012). Discovering data from these meta-modes supported the translational research component of Leininger’s culture care theory and the meta-ethnonursing method. Translational research or implementation science is the foundation for research utilization as evidence-based practice (Ray, et al., 2012). This new meta-ethnonursing method promotes overall expansion and conceptual development of culture care in general for further explication, substantiation, and evolution of Leininger’s theory of culture care diversity and universality and the ethnonursing research method (McFarland, et al., 2012).

Critical Thinking in Nursing Practice with Leininger’s Theory

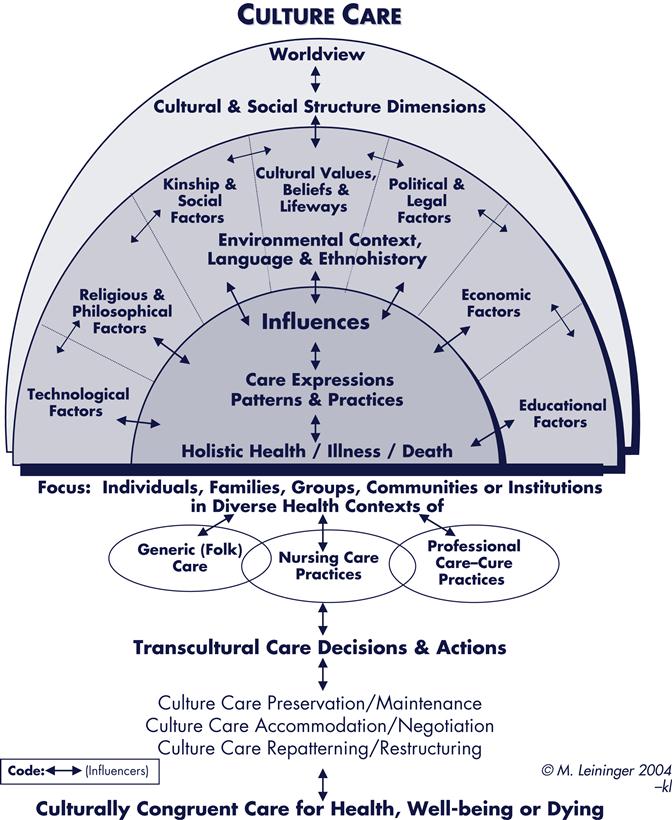

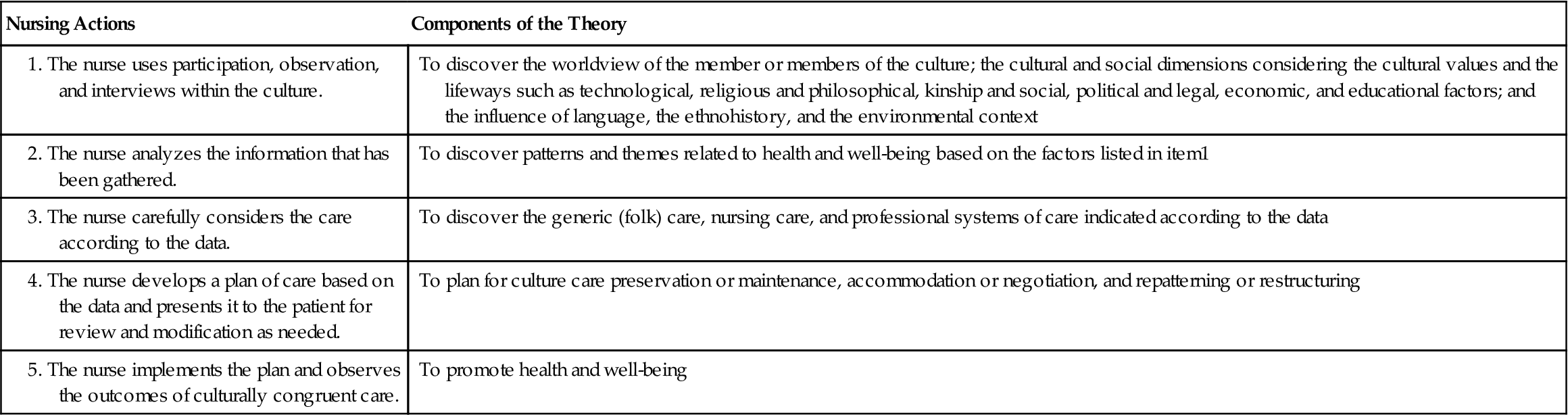

Leininger’s (2002a, 2007) theory of culture care diversity and universality guides practice by assisting nurses to be culturally aware of and sensitive to individual cultures; then to groups and families; then to institutional, regional, and community, societal, and national cultures; and eventually to global human cultures. The sunrise enabler (Figure 18-1) guides decisions and nursing actions through a process focused on specific components of the theory as noted in Table 18-1.

TABLE 18-1

Critical Thinking in Leininger’s Theory

The sunrise (model) enabler (see Figure 18-1) was revised and renamed enabler (Leininger in Leininger & McFarland, 2006, p. 25) to clarify it as a visual guide for exploration of cultures. As Leininger (1995d) stated, “This model should not be viewed as a theory per se, but rather as a depiction of the multiple components of the theory” (p. 107). Therefore, using the enabler, the nurse systematically progresses through the major care constructs and social structure dimensions of the theory with the goal of providing culturally competent and congruent care.

Beginning at the top of the figure, culture care is the overriding component of the enabler followed by worldview and then cultural and social structure dimensions. Worldview refers to the way in which people of a culture perceive theirparticular surroundings or universe to form certain values about their lives. The cultural and social structure factors encompass components of technological; religious and philosophical; kinship; political and legal; economic; and educational factors. These components are studied through participation, observation, and interview research techniques. Many specific study examples can be found in published transcultural research reports in articles, book chapters, dissertations, doctor of nursing practice (DNP) capstone projects, and master’s theses.

Leininger (2002b) specified that nursing care preservation and maintenance be used to enable people of a particular culture to “retain or maintain meaningfulcare values and lifeways for their well-being, to recover from illness, or deal with handicaps or dying” (p. 84). Accommodation and negotiation involves actions and decisions that help the people in a culture “adapt to or negotiate with others for meaningful, beneficial, and congruent health outcomes” (p. 84). Repatterning and restructuring helps “clients reorder, change, or modify their lifeways for new, different, and beneficial health care outcomes” (p. 84)…“while still respecting their cultural patterns and beliefs” (Leininger, 1995d, p. 106).

In most cultures the family is an important factor in care. Wehbe-Alamah (2011) reported the findings from her qualitative ethnonursing study of the culture care of Syrian Lebanese immigrants in the midwestern United States. She used the three modes from the CCT to describe her discovery that the provision of culturally congruent care was centered around the family. Culture care preservation was maintained by requesting that nurses avoid pressuring relatives of deceased Muslim patients to give consent for organ donation or autopsy because Muslims believe their bodies are a gift from God and themselves as trustees of this gift (2011). In order to practice culture care accommodation in the provision of culturally congruent care for Syrian Muslims, the nurses and other health care providers in an inpatient setting were encouraged to consider negotiating the number of visitors and duration of visits. Wehbe-Alamah (2011) found that the presence of a supportive network of family members and friends holds great importance for Syrian Americans as this is considered an essential caring practice as well as a social, religious, and cultural obligation.

McFarland and Eipperle (2008) addressed the issue of integrating the theory of culture care diversity and universality into advanced practice nursing in the roleof the family nurse practitioner (FNP) in providing culturally congruent care primary care contexts (p. 49). They discuss potential for future expansion of the theory in nurse practitioner practice. Given that culture care is a core competency domain for family nurse practitioners (U.S. Department Health and Human Services [DHHS], 2002), they stress the need for nurse practitioners to recognize the often missing component of culture care in nursing.

The nurse practitioner needs to be able to sensitively and competently integrate culture care into contextual routines, clinical ways, and approaches to primary care practice through role-modeling, policymaking, procedural performance and performance evaluation, and the use of the advanced practice nursing process. By using Leininger’s sunrise enabler (Leininger & McFarland, 2006) and the three care modes to guide nursing actions and decisions, we predict the nurse practitioner would be able to provide culturally congruent, safe, meaningful, and beneficial care to clients in primary care contexts (pp. 49-50). McFarland and Eipperle (2008) list six criteria for theory application in advanced practice nursing:

1. Be inclusive rather than exclusive.

2. Foster a focus on the whole person rather than the disease or illness.

3. Include consideration of the patient’s/family’s/significant other’s perception of the situation.

4. Be holistic in nature which is helpful to both practice and documentation.

5. Facilitate autonomous nursing practice (aspect of professionalism along with knowledge and service).

6. Encourage diverse ways of knowing, including empirics, ethics, aesthetics, personal knowing, and sociopolitical knowing (p. 52).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree