Web Resource 5.1: Pre-Test Questions

Before starting this chapter, it is recommended that you visit the accompanying website and complete the pre-test questions. This will help you to identify any gaps in your knowledge and reinforce the elments that you already know.

Learning outcome

On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to:

- Examine the five personality traits and understand how they articulate with the different learning styles

- Analyse different learning styles and appreciate how they can impact on the practice and application of facilitating learning

- Appraise the different teaching theories and how they apply to your preferred learning style and teaching delivery

Personality Traits

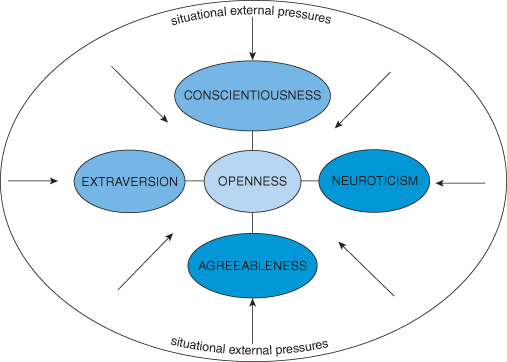

The link between personality and the pattern of a person’s behaviour, thoughts and emotions is described as being unique and remaining consistent for most of a person’s life. Goldberg (1993) defined the following five key factors as representing the basic scaffolding that underpins all personality traits.

Openness: the extent to which a person is perceived as being receptive to new ideas, imaginative, intellectually curious and creative, making them a ‘blue sky thinker’ who is able to see the bigger picture and possible opportunities.

Conscientiousness: someone who scores highly in this trait would make an ideal employee because they strive to achieve, are well organised, strategic in their approach to work and are forward planners. This type of person is regarded as reliable and intelligent. The negative aspect of this trait is that the person can also be viewed as a workaholic and a bit of a perfectionist.

Extraversion: a person who scores highly in this trait is seen as being full of energy and enthusiasm, motivated to get on with the job in hand. This aspect of a person’s personality means that he or she enjoys communicating and is not afraid to assert him- or herself; this makes the person a leader rather than a follower. Introverts might find this type of person overbearing and difficult to get along with.

Agreeableness: describes the extent to which a person is concerned about the feelings of others and how easily he or she forms bonds with other people. Generally a person who has a greater degree of this trait is viewed as considerate, friendly and willing to make compromises. The downside of this trait is that this type of person may spend too long negotiating with others and getting bogged down by the emotional/social concern that individuals have.

Neuroticism: describes the extent to which a person reacts to perceived threats and stressful situations. For those who score highly in this trait, they are sometimes referred to as emotionally unstable because they are vulnerable to stressful situations. For those who score low in this trait, they may be perceived as being emotionally cold and distant because they remain calm in stressful situations.

Everyone shares these traits to a lesser or greater degree and situational influences will also impinge on them (Figure 5.1). Even the most extravert person will seek solitude some of the time. Depending on which traits are more dominant in the mentor will affect how a mentor builds a rapport with a student and how the relationship develops.

Personality Traits and Situational Pressures

The compatibility of different personality traits can form the basis for a positive means of developing creativity and shared motivation, or be negative and a source of conflict.

A good team requires a skill mix, where personalities complement each other rather than aiming for cloning everyone to be the same.

Activity 5.1

- Thinking of these traits, identify a person with whom you are compatible or someone whose company you enjoy. To what degree do they possess the five personality traits? Are these personality traits compatible with your own traits?

- Now think about a person with whom you are incompatible or someone’s company that you do not enjoy. What traits do they possess and to what extent are these traits incompatible with your own?

- Do you think that the person with whom you are incompatible is aware of his or her personality traits and how they impacted on you?

- How much insight do you have into your own personality traits? How do you think these traits might impact on others?

Self-awareness

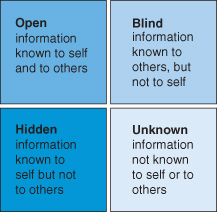

The concept of self is not a static entity because individuals have many roles to play in their lives, each role reflecting an image – such as the professional, the parent and the child. Feedback and insight into what image is being portrayed can be provided by using Johari’s window model of self awareness, which was developed by Luft and Ingham in 1955 (Figure 5.2). The model describes four window panes (open, blind, hidden and unknown); by analysing each pane it is possible to become more self-aware and people oriented, enabling better communication on a one-to-one basis as well as within a team.

The open pane (public self) represents things such as hobbies, personality traits, likes and dislikes. When a student first starts working with a mentor, this pane will be relatively small. As the two get to know each other and share information, it will enlarge. The ultimate goal would be for the mentor to establish an atmosphere of openness and trust so that the hidden and blind panes are reduced and the open pane is enlarged.

The blind pane is the area that represents things that are not apparent to the individual, such as mannerisms and non-verbal cues. It may be that an individual believes that he or she is doing a really good job of explaining something when in fact the opposite is true. Tactful feedback will enable the individual to process the information and act on it, thus encouraging personal growth and personal development. The reverse may also be true – a student may be blind to what he or she is good at. The mentor should encourage and enable students to recognise their strengths, thereby encouraging confidence and competence in their own abilities.

The hidden pane represents the private self of an individual that he or she may not want to disclose to others. It is important to develop a safe and non-judgemental environment where both mentor and mentee can self-disclose and reduce blind behaviour through effective feedback, avoiding concealment of relevant information.

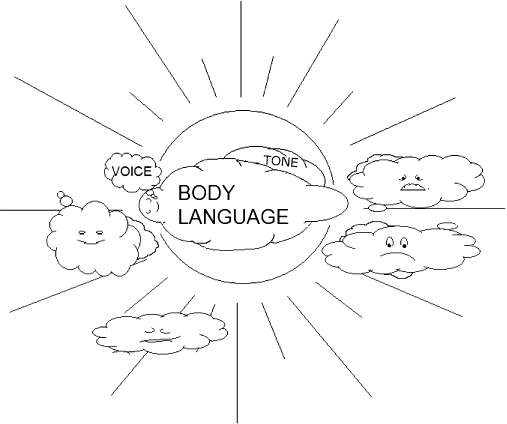

The unknown pane may be buried in the person’s subconscious or be learnt behaviour which may not be open to that person or others. However, according to Mehrabian (1981), consciously or inadvertently, we are constantly communicating – verbal communication making up only 7%, tone of voice being responsible for 38% ,whereas the majority 55% of communication is transmitted via body language; this is open to less censure and thus others may gain insight into some of what is behind this pane. It is worth remembering that all behaviour sends a message conveying attitudes, feeling, beliefs and prejudices, and all communication is irreversible.

The classical scholar and psychologist, William James (1892), described the self as having four components. These consist of a spiritual, materialistic, social and bodily self, which combine to provide a unique sense of individuality (Table 5.1).

Table 5.1 Four components of self

The image of self and self-esteem can provide confidence in one’s own abilities or tensions and anxiety which can lead to poor work performance.

Becoming self-aware enables individuals to recognise the values, beliefs, feelings and behaviours that they hold and that may impact on others. An open mind is required to recognise personal biases and to embrace new ideas and encourage other people’s views. Self-awareness should be a never-ending journey of discovery for the individual. It is also one of the guiding principles for those supporting learning of others in the workplace. Individuals who do not establish their own sense of individuality will have a narrow view of the world, fail to recognise their own prejudices and will be reluctant to change.

Activity 5.2

Using Johari’s window (Figure 5.2 ) identify the various aspects of your nature:

1. Consider how these aspects might impact on your mentoring of students.

2. Has anyone provided you with feedback, such as you are easy to talk to, of which you were previously unaware?

3. Do you convey genuine positive regard and a respectful interest and curiosity towards students or do you convey impatience, superiority or a judgemental attitude?

Did the feedback inspire you to make constructive changes?

Unfortunately, knowing what attitude someone holds about a subject does not provide insight into what behaviour a person will demonstrate. Attitudes cannot be seen; they can only be inferred (Mullin 1996, p 117). It has been demonstrated that what is said by an individual can be very different to the actions they display (Luft and Ingham 1955).

Activity 5.3

Thinking about your own role as a health professional who discusses various aspects of health improvement, such as healthy eating, weight loss and smoking cessation:

- Do you provide a good role model as a health professional?

- Do you practise what you preach?

- Thinking about your answer, why do you think that this is the case?

- Do you think that the students whom you mentor will notice this dichotomy?

- Do you think that the students will be influenced by your example?

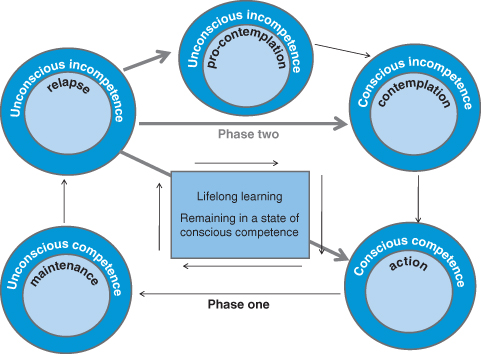

Prochaska and DiClemente (1984) developed a behavioural change model that identified five stages of change:

1. Pre-contemplation (carrying out a behaviour without giving any thought for change, e.g. as in smoking)

2. Contemplation (starting to think about changing the behaviour such as giving up smoking)

3. Preparation (looking at the various ways of making a change and setting a date to start smoking cessation classes)

4. Action (the day arrives and the plan is put into action for change to happen)

5. Maintenance/relapse (the plan goes well, but there is a possibility that there is a lapse to previous behaviour – just one cigarette won’t hurt).

This behavioural model fits well with aspects of Dubin’s (1962) cognitive unconscious incompetent model of learning (Figure 5.3). Howell and Fleishman (1982) also laid claim to developing the behaviour model.

Figure 5.3 Cognitive and behavioural change models.

(Adapted by Thompson using the models of Prochaska and DiClemente [1984] and Dubin [1962].)

The first stage of the unconscious incompetence model uses the pre-contemplation stage of Prochaska and DiClemente’s (1984) model to articulate. Here the individual is unaware of gaps in competence and, therefore, does nothing to enhance this aspect of his or her learning

The second stage of Dubin’s (1962) model is conscious incompetence which again correlates with Prochaska and DiClemente’s model because the person is in the stage of contemplation. Realisation develops as the person becomes aware of a need to enhance knowledge and skills and bring about behavioural changes.

The third stage of Dubin’s model is conscious competence; once again this correlates with the action stage of Prochaska and DiClemente’s model. The person now sees the gaps and makes a conscious effort to acquire new knowledge and skills.

The fourth stage of Dubin’s model, unconscious competence, is where the person is now confident in his or her own ability and competent in the skill. Once again this fits with Prochaska and DiClemente’s model at the level of maintenance, which allows a person to carry out a skill on ‘automatic pilot’, up to the point of new changes in practice or lack of use.

The potential fifth stage can occur when decay of skills occurs and there is a lapse back into unconscious incompetence (Dubin’s model) or behavioural relapse, as in Prochaska and DiClemente’s model. To prevent this happening life-long learning must be embraced so that a person ideally remains in the stage of conscious competence. This will ensure that the person will be open to learning from others, reflecting on evidence-based best practice and thus preventing complacency and a move into unconscious competency or unconscious incompetency.

For more information on these models visit www.businessballs.com/consciouscompetencelearningmodel.htm#origins of conscious competence learning model.

Learning Styles

Learning is a broad term that encompasses the acquisition of knowledge, skills, attitudes and social/cultural values and behaviours. Wenger (1998, p 226) argued that what differentiated learning from mere doing was that ‘learning’ (whatever form it took) altered a person by changing his or her ability to participate, belong and negotiate meaning. Coffield (2008, p 7) suggests that the most important thing about having a learning definition is that it reflects the individuals beliefs and practices so that when challenged, the person is able to defend the stance that he or she had chosen. Hargreaves (1997) suggested that there is psychological and social significance to learning – learning a job through apprenticeship is more than just learning a skill to earn a living: it is to join a community, to acquire a culture, to demonstrate a competence and to forge an identity. In short, it is to achieve significance, dignity and self-esteem as a person.

The ability to learn will depend on the individual’s potential and attitude to learning. Attitudes to learning will be shaped by the negative and positive feedback that people have previously received and by the cultural and environmental aspects of their lives.

Activity 5.4

- Thinking back to your school days, did you enjoy learning maths?

- Was motivation for the subject influenced by the feedback that you got from the teacher?

- How did the teaching style promote/delay your level of understanding?

- Did the teacher’s relationship with you influence your understanding of the subject?

- How has this influenced your attitude towards the subject?

Kiger (1997) suggests that, when starting a new task for the first time, it is not surprising to note that the emphasis is on the ‘what needs to be learnt’ rather than ‘how the information would best be learnt’. This ‘automatic, knee-jerk’ approach to learning can limit the effectiveness and efficiency of both the individual’s understanding of what is needed to carry out the task and an inability to disseminate this information to others.

The facilitation of learning is an interactive and mutual process influenced by a complex network of factors that make learning challenging, fun, satisfying and sometimes painful. Commitment is required from both the student and the mentor so that the student can enhance his or her learning and personal development. The mentor must be reliable, consistent, have a strong sense of whom he or she is and be able to accept the new ideas and challenges that each student will bring. Remember that conflict and challenges are inevitable, but combat is optional.

Conflict tends to be viewed in negative and destructive terms. Most people have not learnt the skills to enable a mutual solution-focused resolution, or they lack the commitment for resolution to take place. Good communication, empathy and respect are key to achieving a healthy outcome. When conflict occurs it is important to do the following:

- Acknowledge that there is a problem

- Listen with empathy, trying to see things from the other person’s perspective

- Reflect back on your understanding of what the other person is saying

- State your views (this can be cathartic)

- Maintain a dialogue in a climate of mutual consideration and respect

- Your aim should be to achieve a win/win situation.

There are many ways of learning and the best approach will depend on what task is being carried out, the situation and the personality type of both the mentor and the student. If mentors know their own preferred learning styles they will be better placed to appreciate how this can influence the way in which they facilitate learning. By learning and using a range of approaches, the mentor will be better able to provide a repertoire of teaching methods that will accommodate students with different learning styles.

Web Resource 5.2: Should We Be Using Learning Styles? (Learning and Skills Research Centre)

Web Resource 5.2: Should We Be Using Learning Styles? (Learning and Skills Research Centre)

For more in-depth information and a critical overview on learning styles visit the accompanying website, and the following websites: www.texascollaborative.org/Learning_Styles.html and www.doceo.co.uk/heterodoxy/styles.htm.

According to Entwistle et al (2001) and Marton and Säljö (1976) two levels of learning can take place – deep (where in-depth understanding is sought) and superficial (where facts are memorised in a rote learning fashion). The depth of learning will depend on the nature of the learning task that is required. If multiplication tables must be learnt, then superficial learning may be ideal, whereas, if logical and original thought are to be used as in assessment of healthcare needs, this level would be inadequate.

More in-depth understanding of the concepts that underpin deep and surface learning can be found by visiting the accompanying website: www.newhorizons.org/future/Creating_the_Future/crfut_entwistle.html.

Activity 5.5

To enable you understand your own preferred learning style, please read and complete the activity below.

Imagine that you have just purchased a new piece of computer software and are about to use it for the first time. How might you approach this task?

1. You sit down with the instruction booklet and read through it thoroughly before using the software.

2. You start the task straight away. Ask others for help if you get stuck. Once mastered you are keen to move on to something new.

3. You ask for advice from others, ponder the advice and weigh up the different ways of doing things before you start using the software.

4 You glance through the instruction booklet, but are eager to put the theory into practice.

Web Resource 5.3: Activity 5.5 Feedback

Web Resource 5.3: Activity 5.5 Feedback

To see which style you preferred, visit the accompanying web page.

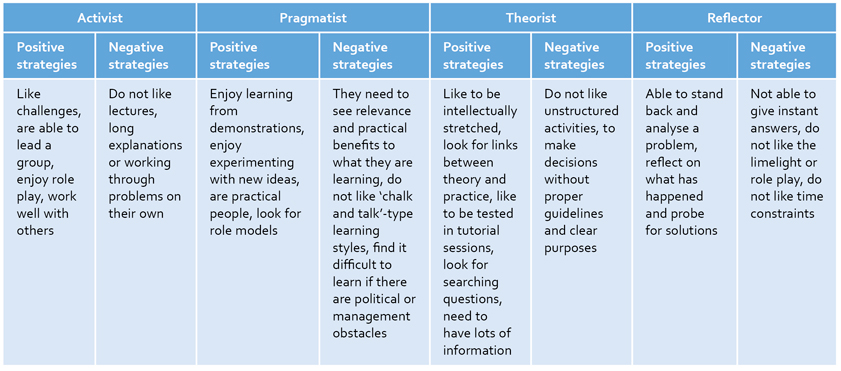

The positive and negative aspects of each learning style can be identified in Table 5.2.

Table 5.2 Learning styles

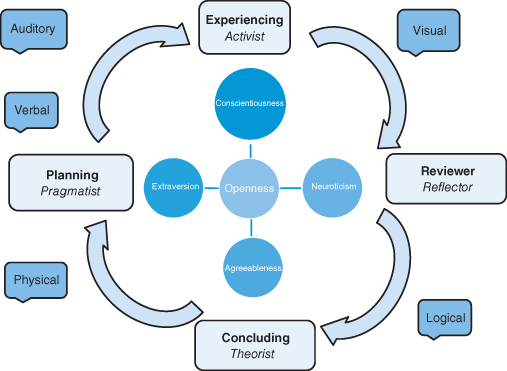

Honey and Mumford (2006) point out that there is an association between the learning cycle and the learning styles:

- The activist style is associated with the experiencing cycle.

- The reflector style is associated with the reviewing cycle.

- The theorist style is associated with the concluding cycle.

- The pragmatist is associated with the planning cycle.

Therefore, teams that have a range of different learning styles will work well together because they each have there own strengths and weaknesses.

To promote and reinforce learning, the different lobes of the brain should be activated by stimulating different senses. This can be achieved by stimulating a different range of senses:

- Visual (spatial) display of imagery to maximise understanding

- Aural (auditory) stimulation using music or sounds to achieve recollection

- Verbal (linguistic) using rote learning and writing information down to reinforce knowledge

- Physical (kinaesthetic) approach using hands and sense of touch

- Logical (mathematical) following rules and systems that use reasoning

- Social (interpersonal) learning in groups by sharing ideas and challenging attitudes and behaviour

- Solitary (interpersonal) self-directed study.

These learning styles, different senses and self-image concepts are encapsulated in Figure 5.4.

Figure 5.4 Learning styles, sensory stimulation and self-concept diagram.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree