Introduction

Chapter 1 was about managing your resources so that you can study effectively. The overall aim of this chapter is to build on the previous one and develop your learning skills. This is achieved by identifying what learning is and how we do it. There is an explanation of different learning styles and how these can affect your studying, and an opportunity to identify your personal learning style. Knowing how you prefer to learn can help guide you through your course, although you need to be aware that your preference can change according to what you are studying.

Being an adult learner

It is important that you take responsibility for your own learning. Higher education is very different from school. As an adult learner, it is up to you to identify what you want to learn and how much effort you are going to give to learning – only you can successfully complete the course.

The aim of this book is to help you to become an independent and self-directed learner; this means you will be able to identify what you need to learn and to access the information you require without the assistance of a lecturer. Additional mechanisms in your place of learning will support and help you during the course, but you need to recognize how you take responsibility for your own learning.

When you enter a professional course in a university, you have earned the right to be there by a rigorous selection procedure. As an adult learner, you enter education with the status of an adult, a range of experiences and the motivation to gain a qualification; you are there because you choose to be – this is not compulsory education. Psychologists call this ‘intrinsic motivation’; it is the strongest driving force there is.

A key proponent to any success is motivation – a sense of purpose is perhaps the most crucial aspect of learning, you must want to study. For example, if you are undertaking a pre-registration midwifery course purely because you couldn’t think of anything else to do, you are not increasing your chances of success; your driving force – or motivation – may be weak.

Motivation is so important when you are embarking on something new and challenging. There are going to be times when you find the going difficult; regardless of what you have identified as motivating you at the start of a new course, your motivation will change during the course.

Briefly note down what has motivated you, either to start a new course or to learn a new skill.

Briefly note down what has motivated you, either to start a new course or to learn a new skill.

Briefly note down what has motivated you, either to start a new course or to learn a new skill.

Briefly note down what has motivated you, either to start a new course or to learn a new skill.Sometimes your motivation is going to be better, sometimes worse. This might be for a variety of reasons. You might have concerns about:

■ financial insecurity

■ meeting new people

■ having reduced time available for family and friends

■ making time for study

■ not understanding the course and/or the academic language used by your teachers and peers.

A new course is exciting and will bring about a change in your life; this change might cause you stress. Stress is not always a negative thing, only when you are experiencing too much pressure – or stress – does it become a problem. A degree of pressure stimulates us and can be a very positive thing but, if not managed correctly, this pressure can become too much and we are unable to cope. It is important to be able to recognize these signs and symptoms in yourself and others; only through recognition and then doing something to create a change will you adequately address the problem. Chapter 1 identified some positive strategies that can be used to resolve some of these issues.

Remember what motivated you to start the course in the first place, and do something positive such as taking some exercise, fi nding a solution to your problem or talking to someone (either a professional – such as a counsellor – friends or colleagues).

Remember what motivated you to start the course in the first place, and do something positive such as taking some exercise, fi nding a solution to your problem or talking to someone (either a professional – such as a counsellor – friends or colleagues).

Remember what motivated you to start the course in the first place, and do something positive such as taking some exercise, fi nding a solution to your problem or talking to someone (either a professional – such as a counsellor – friends or colleagues).

Remember what motivated you to start the course in the first place, and do something positive such as taking some exercise, fi nding a solution to your problem or talking to someone (either a professional – such as a counsellor – friends or colleagues).What is learning?

Learning is something we do practically every day so it may seem a bit strange to be asking what we mean by it. However, knowing how learning occurs may help you to become a more effective learner.

■ Learning is any more or less permanent change in behaviour, knowledge or belief.

■ To experience this change we need to be exposed to new ideas or skills.

■ Sometimes we are not conscious of the learning experience; examples such as reciting a television advert or singing a song prove that you can learn without deliberately trying. This is called ‘passive learning’.

You can learn useful things by passive learning; for example, the signs and symptoms of illnesses frequently encountered in clinical practice. Such learning is superficial because you do not necessarily understand why it happens. So, although you might be able to copy the skills you have observed a more experienced practitioner perform, will you be able to modify the skill when a new and slightly different situation occurs?

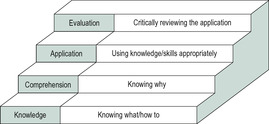

Professional practice is more than just copying the behaviour of our predecessors and learning facts by rote. The Nursing and Midwifery Council’s (NMC’s) Code of Professional Conduct requires practitioners to ‘… take part in appropriate learning and practice activities that maintain and develop your competence and performance’ (NMC, 2008, p. 4). This means actively engaging in the learning process, which occurs when you understand the principles behind the concepts and skills being studied. It can help to view learning as a progression from the acquisition of knowledge through to higher-level mental activities. Figure 2.1 represents this progression, starting from being able to remember straightforward facts, such as labelling a diagram of the heart (simple recall or knowing what the various parts are), through to being able to explain the function of the heart valves or the reason why the muscle layer of the left ventricle is thicker than the right, which represents a higher level of learning (the ability to comprehend the concepts you are studying).

Going beyond this level takes you to the stage of being able to apply your knowledge. For example, if you have a patient with damage to the left ventricle following a coronary thrombosis, you will be able to plan nursing care that takes the impaired circulation into account. By observing the effect of exercise on the patient, such as the degree of breathlessness after walking a prescribed distance, you will be able to evaluate the effect your plan has had on their heart.

Simply knowing and being able to perform are important but lower-order activities, and applies to someone who follows orders. However, midwifery and nursing students are studying to be able to act independently and to exercise professional judgement. You need to make links between theory and practice – what Mallik (2005, p. 320) refers to as the ‘aha’ moment; active participation in the learning process is essential.

Learning is more than the mere acquisition of facts, it involves a range of intellectual activities including the ability to make judgements on abstract matters such as topical issues or ethics.

Think about some of your political, religious or ethical beliefs.

Think about some of your political, religious or ethical beliefs.

Think about some of your political, religious or ethical beliefs.

Think about some of your political, religious or ethical beliefs.• How did you acquire them?

• Do you understand the principles upon which they are based?

• How do they affect your practice?

• Have you at any time subjected them to serious critical scrutiny?

Often, we pick up our beliefs from influential people around us, such as parents, religious ministers or teachers, and we accept them because we respect the authority of the person teaching us; we expect that person to know what he or she is talking about. Such learning tends to be passive, resulting from being constantly exposed to the same ideas since childhood; and discussion and debate with friends or family with similar views will not encourage a critical perspective.

So how do we learn?

The concepts of learning and memory are closely related. When we need to perform a skill, recall an item of knowledge or explain something, we draw on our memory, but we can only draw on what is already there. Knowing how memory works can help you develop effective learning skills. Although memory is an incompletely understood concept, the Atkinson–Schiffrin model, described by Malim and Birch (1998,p. 291), explains memory as a series of steps (Figure 2.2).

|

| FIGURE 2.2 (adapted from Malim and Birch, 1998) |

The next activity demonstrates how we are constantly bombarded with sensory input.

Stop for a moment and focus on the information you are receiving via your five senses:

Stop for a moment and focus on the information you are receiving via your five senses:

Stop for a moment and focus on the information you are receiving via your five senses:

Stop for a moment and focus on the information you are receiving via your five senses:• What is happening outside your body?

• What is your body telling you about inside you – have you any aches and pains?

All of this information – most of which you don’t need – is coming at you while you are trying to learn from a lecture or demonstration and is stored in your short-term memory. Sensory inputs are encoded, we try to give them meaning, and those that have no relevance are discarded. If you can understand lecture material, i.e. it makes sense to you, you can give it meaning in relation to your own experience, then you have successfully encoded it and it will enter and remain in your long-term memory. However, if you can’t make sense of it, it will not be retained. Only information stored in the long-term memory can be recalled. Memory is dependent on making sense of information.

To make sense of new material (the encoding process), we have to work hard to establish links between what we already know and the new information. Consider the following example.

When studying orthopaedics you come across the term ‘subperiosteal cellular proliferation’. At first glance, you may just see a complicated medical term but, when you look carefully, you will see that there are some familiar components:

When studying orthopaedics you come across the term ‘subperiosteal cellular proliferation’. At first glance, you may just see a complicated medical term but, when you look carefully, you will see that there are some familiar components:

If you are given pre-reading or worksheets before a lecture or seminar then be sure to complete them. If you do, then the session is more likely to make sense to you, and you can ask questions and clarify any points that you are not sure of.

If you are given pre-reading or worksheets before a lecture or seminar then be sure to complete them. If you do, then the session is more likely to make sense to you, and you can ask questions and clarify any points that you are not sure of.

When studying orthopaedics you come across the term ‘subperiosteal cellular proliferation’. At first glance, you may just see a complicated medical term but, when you look carefully, you will see that there are some familiar components:

When studying orthopaedics you come across the term ‘subperiosteal cellular proliferation’. At first glance, you may just see a complicated medical term but, when you look carefully, you will see that there are some familiar components:• sub means ‘below’

• peri means ‘around’

• cellular refers to cells

• proliferation means ‘production of a large number’.

So you can work out that a large number of cells are being produced, but where exactly? You have to try to understand the meaning of subperiosteal. At this point, you might need a dictionary to look up the meaning of periosteal (around the bone – os is Latin for bone). Looking at a diagram of a bone in an anatomy book will show you that the periosteum is the tissue that surrounds bone, so subperiosteal refers to the site below the periosteum where the cells are produced, hence cellular proliferation. Making sense of something like this is an encoding process – you are making sense of it.

If you are given pre-reading or worksheets before a lecture or seminar then be sure to complete them. If you do, then the session is more likely to make sense to you, and you can ask questions and clarify any points that you are not sure of.

If you are given pre-reading or worksheets before a lecture or seminar then be sure to complete them. If you do, then the session is more likely to make sense to you, and you can ask questions and clarify any points that you are not sure of.Making new links does not always happen the first time you try to learn something, effort is required. If you can recall a time when you learned a skill, such as riding a bike, you will remember how you got some things right and some things wrong. Eventually, as you persevered you became relatively skilful and were able to perform in a fairly fluent way. It is believed that when we are learning we are making new circuits between our neurons (brain cells); these neural pathways are physical structures and are activated when we need to recall something. It may be helpful to use an analogy to explain this concept.

Think about a number of towns without any road or rail links; communication between them would be impossible. Laying down new roads and railway lines is a diffi cult and time-consuming job but, once they have been established, traffic can travel rapidly between the towns.

Think about a number of towns without any road or rail links; communication between them would be impossible. Laying down new roads and railway lines is a diffi cult and time-consuming job but, once they have been established, traffic can travel rapidly between the towns.

Think about a number of towns without any road or rail links; communication between them would be impossible. Laying down new roads and railway lines is a diffi cult and time-consuming job but, once they have been established, traffic can travel rapidly between the towns.

Think about a number of towns without any road or rail links; communication between them would be impossible. Laying down new roads and railway lines is a diffi cult and time-consuming job but, once they have been established, traffic can travel rapidly between the towns.Once the hard work of understanding new concepts and developing new skills has been done, the neural pathways have been established and the information traffic can speed rapidly around the brain. This is why learning has been described as a more or less permanent change.

So why do we forget?

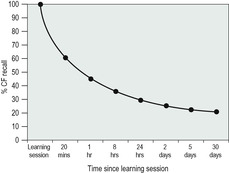

What are you good at remembering? Faces, names, what people say, football matches? I can remember people’s faces and names – we are all able to recall certain things better than others. Spending time and effort does not necessarily guarantee success in learning, but it is how we use it that is important. Figure 2.3 shows the effect when students are stimulated to recall information, or practise skills, soon after being exposed to them. If this is done frequently, the chances of forgetting are reduced. Frequency of recall is the key factor in remembering.

The main principle is to give yourself as many opportunities as possible to rehearse: for example, practising a skill as often as you can and as soon as possible after being taught it (see Chapter 10). For knowledge and understanding, try to set yourself a series of short tests, based on the information you have read or been taught.

Get yourself a small address book that will slip in your pocket. Everything from passwords, door codes, how to document a palpation can be written here. Until this knowledge is second nature, you can flip to letter ‘P’, for example, and look up how to accurately document a palpation.

Get yourself a small address book that will slip in your pocket. Everything from passwords, door codes, how to document a palpation can be written here. Until this knowledge is second nature, you can flip to letter ‘P’, for example, and look up how to accurately document a palpation.

Get yourself a small address book that will slip in your pocket. Everything from passwords, door codes, how to document a palpation can be written here. Until this knowledge is second nature, you can flip to letter ‘P’, for example, and look up how to accurately document a palpation.

Get yourself a small address book that will slip in your pocket. Everything from passwords, door codes, how to document a palpation can be written here. Until this knowledge is second nature, you can flip to letter ‘P’, for example, and look up how to accurately document a palpation.Sometimes, perhaps because we are anxious (e.g. during an examination), we fail to recall. You might have had the experience of not being able to answer a question in an exam and then, when you leave the room, the answer comes to you.

One way to overcome this is to visualize the brain as a channel that is constricted, preventing the flow of information; relaxation techniques can be helpful in situations like this. Imagining the walls of the channel relaxing helps you to imagine the flow of information returning. By relaxing and thinking loosely about the question, some ideas may begin to spark and these might lead to other relevant ideas – the information traffic starts to flow again.

Knowing things

How can we know anything? For example, how do you know that the South Pole exists? Or how do you know that oxygen moves into cells? The chances are that you ‘know’ because someone told you. This type of knowledge is second-hand knowledge – sometimes known as propositional knowledge.

Is there a difference between knowing and knowing about? You may know about the indigenous people of Australia, but how deep is your knowledge? Do you know them as well as someone who has lived with them?

Where does knowledge come from?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree