CHAPTER 1 Learning management (and managing your own learning)

After studying this chapter, the reader should be able to:

Critically reflect on their own learning needs as a health service manager and discuss strategies and programs that would meet those needs.

Critically reflect on their own learning needs as a health service manager and discuss strategies and programs that would meet those needs.INTRODUCTION

This chapter introduces some concepts and principles regarding management education that we hope will be useful to you in managing your own learning. Managers come to the role through a variety of pathways and take different routes as they develop in this role. However you got there and whatever the organisational environment in which you find yourself, you will need to equip yourself to deal with the demands of your role on an ongoing basis. Furthermore, as a manager, you are also responsible for addressing the training and development needs of your staff and creating an institutional environment that supports organisational learning.

A FRAMEWORK FOR MANAGEMENT EDUCATION PLANNING IN HEALTH SERVICE ORGANISATIONS

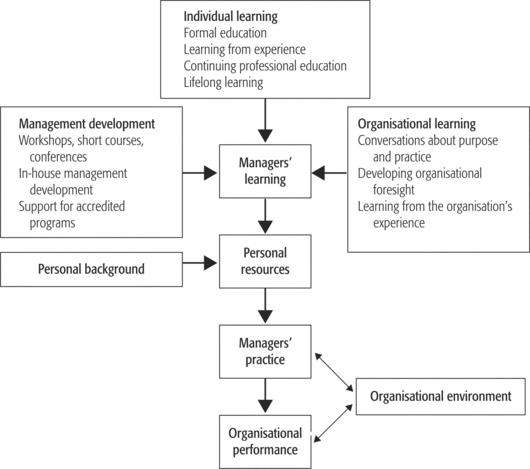

The logic of this chapter is illustrated in Figure 1.1. This figure starts at the bottom with organisational performance, which we assume to be the main rationale for investing in management. Reading from the bottom upwards, the diagram suggests that organisational performance is shaped (at least in part) by managers’ practice (what managers actually do) and that how well they practise depends on their ‘capabilities’. The diagram shows how the personal resources that managers draw on are shaped by both their personal backgrounds and by their learning. It traces managers’ learning back along three paths: first, individual learning (in both formal and informal settings); second, the learning that is promoted through formal management development programs; and finally, the learning that is sustained by the structures, processes and culture of the organisation (organisational learning). This diagram provides a framework for the material presented in this chapter. Of course there are other ways of representing management education, but this model serves our present purpose. In particular, it relates management education to organisational performance as its fundamental reference point; second, it encompasses formal learning and learning by experience; and finally, it encompasses individual learning, institutional management development and organisational learning (Pei et al 2000).

The questions which arise from the model presented in Figure 1.1 are:

ORGANISATIONAL PERFORMANCE

Of course managers are not wholly and solely responsible for organisational performance. Other factors that contribute include: organisational history, the functioning of the wider service systems (including government policy and direction setting), funding flows and the numbers and quality of staff. These other factors (‘organisational environment’ in Figure 1.1) set the context in which managers work and the substratum on which they work. Priority setting in management education must be oriented around managers’ contribution to organisational performance. Freedman and Stumpf (1982, pp 8–9) explain:

WHAT IS IT THAT MANAGERS DO?

To trace how managers add value to the work of their organisations we need to be able to describe what managers do. The classic approach to describing what managers do was based on the particular functions that explain the manager’s role in relation to the life and work and development of the organisation. Thus Fayol (1916) identified five basic functions of management: planning, organising, coordinating, commanding and controlling. This list has variously expanded to POSDCORB: planning, organising, staffing, directing, coordinating, reporting, budgeting (Gulick & Urwick 1973); and contracted to POLC: planning, organising, leading and controlling (Fulop et al 1992).

Mintzberg (1973) offered his own variant with a focus on the roles rather than the functions: interpersonal (figurehead, leader, liaison); informational (monitor, disseminator, spokesperson); and decisional (entrepreneur, disturbance handler, resource allocator, negotiator). Mintzberg (1973) also summarises a range of activity studies of managers’ work which in sum demonstrate that managers spend a lot of time either working with people or working with information. These studies have clear implications in terms of identifying the kinds of basic skills that managers need.

A third approach to defining what managers do centres around the struggles and challenges which from time to time preoccupy managers. Pei (1999) has used the struggles of managers as one of the foci of her study of management training needs in China. Pei’s focus on the current struggles of managers enables her to identify the areas where managers think that they are, or could be, making a difference. This provides a starting place in identifying areas where training might make a difference and the kinds of competencies that could be currently limiting organisational performance. There are educational advantages also in focusing on ‘struggles’. Learning is more effective where it is structured around questions and possibilities that relate to the struggles that the learner is facing in their daily life (Candy 1991). It is a double bonus if these are also the areas where an educational investment is likely to have the highest yield in terms of organisational performance.

It is also useful for managers to reflect on the assumptions they make about organisations and what it takes to manage them. Organisations are not always what they seem nor what we would like them to be (Morgan 1998). Schwartz (1990) explains that management textbooks and formal training programs often portray organisations as if they are like a clock. In the ‘clockwork’ organisation people have a shared view of the organisation’s purpose and are committed to it; they are happy in their work; they display low anxiety and cooperate and support one another. If difficulties arise they can be dealt with through the use of rational problem-solving by managers with the appropriate skills and techniques. A different type of organisation that commonly reflects the experience of managers might be called the ‘snakepit’. Here things are falling apart, people put energy into ensuring nothing falls on them, anxiety and stress are constants and people deal with each other for their own purposes or to avoid being used. Managers essentially attempt to just get through the day. Whilst these represent extremes and organisations have elements of both, managers need to equip themselves for the realities of organisational life, not the fantasy (Gabriel 1999, Hirschhorn 1988). The content and manner of learning needs to reflect these realities.

The increasing pace of change and looming uncertainty has led to dramatically changing paradigms of management: from administrative or operational management to strategic management and from strategic management to new forms and practices which are still hard to discern. Some management theorists are drawing on complexity theory as a framework for making sense of contemporary challenges in management. McDaniel (1997) argues that traditional paradigms of management practice are based on a Newtonian world view of stability and ordered change. Managers are constructed as ‘decision makers’ in such paradigms. He describes the emerging paradigm in terms of quantum theory and chaos. According to quantum theory the world is unknowable and unpredictable and observation and measurement are never independent of the observer. McDaniel argues that managers need to factor unknowability into their work styles; for example, recognising the potential significance of small causes. Leadership in uncertain times involves:

Mintzberg (1973) points out that one of the main sources of variation in patterns of management practice is the difference between managers as people, although very different people can be very effective managers. People have different strengths — perceptual, conceptual and in styles of implementation — and different managers draw on their different strengths to create very different management styles.

HOW DO MANAGERS DO WHAT THEY DO?

But what do people need to know in order to be good managers?

Competencies and attributes

Many authors have commented on the kinds of knowledge and skills that managers need. In more recent times these commentaries tend to be cast in the language of competencies. Mintzberg, writing in 1973 (before the rise of the competencies movement), described the skills that managers need as including: interpersonal skills, leadership skills, information-processing skills, decision-making skills, resource allocation, entrepreneurial skills, and skills of introspection (Mintzberg 1973).

The 1995 Karpin report (Industry Taskforce on Leadership and Management Skills 1995) identified the broad areas in which many Australian managers needed to improve. These included: soft or people skills, leadership skills, strategic skills, international orientation, entrepreneurship, broadening beyond technical specifications, relationship-building skills across organisations, and utilisation of diverse human resources. The Karpin report identified frontline managers and supervisors as its major concern, concluding that the majority of them are not being properly prepared for the challenges they face. Following the Karpin report, the Australian National Training Authority commissioned the development of a set of competency standards for frontline managers (FMI; frontline management initiatives) which included: manage personal work priorities and professional development; provide leadership in the workplace; establish and manage effective workplace relationships; participate in, lead and facilitate work teams; manage operations to achieve planned outcomes; manage workplace information; manage quality customer service; develop and maintain a safe workplace and environment; implement and monitor continuous improvements to systems and processes; facilitate and capitalise on change and innovation; and contribute to the development of a workplace learning environment (Griss & Lilly 1996, Pearson Education and Australian National Training Authority 2001).

There have been several studies of the competencies and attributes that characterise good managers in health care, including Rawson (1986), Boldy et al (1989), Harris and Bleakley (1991) and Jain et al (1996).

Rawson (1986) and his colleagues undertook a questionnaire survey of health service managers asking about the skills and knowledge which are critical to their effectiveness and asking where current educational needs were most pressing. They reported that foremost among the educational priorities for middle and senior managers in health services in Australia were personal and interpersonal skills. Some of the highly rated areas of skills and knowledge were: report writing and communicating effectively in writing; leadership abilities; skills and processes in transmitting ideas; staff motivation; dealing with conflict and stress; concepts, implications and laws of industrial relations; computer applications in the health services; conflict resolution; personnel administration; and analysis of financial information.

Boldy and his colleagues (1989) undertook a major study of management problems and professional development needs of managers in health services in Australia. Key issues of concern were: managing change, managing information, dealing with financial constraints, evaluation, corporate planning, human resource management, conflict and staff development. Over 80 per cent of respondents considered that they were not sufficiently involved in executive development activities.

Harris and Bleakley (1991) sought to identify important competencies for health service managers through a focus group process followed by a survey. Thirty practising managers in four focus groups generated 49 competency statements which were then clustered into: decision-making and planning, developing others, financial acumen, leadership, negotiation, personal attributes, and public relations/communication. These statements were then put into a questionnaire and were ranked by 320 health service managers currently participating in professional development. There was a high level of agreement. The clusters were ranked in order of importance: leadership, decision-making and planning, public relations/communications, financial acumen, developing others, personal attributes, and negotiation. There were some differences in the rankings across different sized facilities and managers’ backgrounds. Top professional development priorities were: leadership, negotiation, communication, financial management, problem-solving and decision-making.

Jain et al (1996) surveyed a large sample of managers and management students. The Jain questionnaire conceptualised management capacity in terms of a series of personality characteristics, knowledge and learning items, skill items, and beliefs and values which respondents are asked to rank in terms of their contribution to effective management. Factor analysis across all sub-samples highlighted nurturing, forceful, idealistic personalities, knowledge of social and behavioural theory, skills in political and classical management, and non-materialist and paternalist values.

Similar surveys have been undertaken in Canada (Curry 1989) and the United States (Davidson et al 2000). Both of these studies report findings that are broadly similar to those arising from Australian studies.

Models of managers’ practice

Undoubtedly this is a useful construction of many moments of managerial practice. However, it should not overshadow alternative constructions of managerial practice such as that of Schön (1987), who invites us to think of the manager as an intuitive artist: integrating multiple complex data inputs on the basis of ‘what feels right’; choosing strategies on the basis of a body knowledge (gut feelings); drawing eclectically on different theories and models to rationalise his/her practice after the fact. Schön presents professional practice as artistry and points to the significance of versatility in composing and projecting one’s self. This is about building the ability to engage in early and ongoing reflective practice (Schön 1987). The reflective practitioner in this context is a manager who engages in a critical examination of their action-taking and the underlying thoughts, feelings and values that drive it. It enables managers to develop insights about the aspects of their actual practice that work and those that need changing — it forces them to review their ‘theories in use’ rather than just their ‘espoused theory’ (Argyris 1999). Importantly it releases a capacity for change, generates awareness, choices and options and promotes learning that is grounded in personal and organisational reality (Pedler et al 2001). Many practitioners who have moved into management roles in health care settings have strongly advocated the benefits of this approach to learning and development (Bowerman 2003, Greenall 2004).

ABOUT LEARNING

Pedagogy is about learning and what teachers do to support learning. Certain models of pedagogy have been built into social practice since pre-history: in particular, various forms of ‘watch and try learning’ (ranging from learning kitchen skills to apprenticeship training) and various forms of ‘learning by being told’ (learning histories and geographies, learning the rules). Much of the focus of pedagogical thinking is concerned not with what the teacher does but the settings and experiences that support learning; the sequencing of learning experiences and the learning environments which are rich in such experiences. This is particularly so in adult education and indeed there has been a great deal written about adult learning (Delahaye 2005).

Most of this work takes the view that managers learn most effectively when they have some degree of control over the learning process, learn on their own initiative, are able and willing to diagnose what they need to learn, recognise that their needs are often different to others in different contexts and are able to pursue their specific needs in ways that are meaningful for them. In other words, they are able to take responsibility for their own learning and develop (with help) a capability to learn how to learn (Knowles 1990). Managers usually learn best when they are working reflectively on real-life organisational problems in real time and are able to take new action based on the learning from this reflective process and the input of the different ideas and practices of others (Howell 1994, Kolb 1984). This highlights the importance of interspersing theory, practice and learning and the social character of such learning.

The implications for health services management education would be to highlight the role of learning sets and other forms of self-directed group discussion where managers can discuss new ideas together and explore new languages, new perspectives and new subjectivities with their peers. Action learning offers a framework for such approaches. It is an approach to management and organisation development that integrates or links thought and action with reflection. It involves managers working on real organisational problems, as they occur and in the context in which they occur, engaging in cycles of observation, critical reflection, evaluation and action-taking. This process enhances the capacity of managers to investigate, understand, change and improve their practice and the organisation in which they find themselves (Bowerman 2003, Howell 1994, Revans 1982).

Beyond competencies to learning pathways

Harris and her colleagues (1993) invited 50 managers to participate in five discussion groups to consider the results of their 1991 study of competencies required for health services management (Harris & Bleakley 1991). They invited the managers to identify their preferred educational pathways for developing each competency. By way of example, one of the competencies which they considered was the ability to empathise, listen and respond effectively to another’s statements. Their respondents suggested that developing these skills requires: first, formal academic courses to provide an understanding of relevant theories; second, short courses or workshops for skill development using videos to provide feedback on performance; and third, structured in-house staff development based on an organisation-wide survey of staff needs.

Managers also need to be aware that learning is about change and is often not easy (Bridges 2003, Delahaye 2005). Consciously and unconsciously we can set up obstacles to planning our development and this can also occur in relation to the development of our staff. Many people do not recognise their development needs, think that all development activities involve missing work to attend a training program, do not have enough time or do not bother to set specific objectives or develop action plans. Some realise learning involves change and feel vulnerable in this situation, especially if they view development as working on weaknesses they do not want others to know about. Being a reflective practitioner, with the help of others can enable us to be more aware of our own personal obstacles. This can be an important starting point for learning.

Because of the limitations of the competencies concept and because specifying competencies does not help in terms of identifying learning pathways, we use the more diffuse idea of capabilities as a kind of stepping stone in thinking through the learning pathways through which the necessary competencies may be acquired or developed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree