CHAPTER NINETEEN Leading contemporary approaches to nursing practice

At the completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to:

understand the discrete differences between leadership and management in relation to nursing practice;

understand the discrete differences between leadership and management in relation to nursing practice; appreciate the importance of visionary leaders in facilitating change management in a clinical environment; and

appreciate the importance of visionary leaders in facilitating change management in a clinical environment; andINTRODUCTION

Internationally, contemporary clinical, administrative and policy environments of health care render unique challenges to both health care professionals and consumers (Heath 2002; Hinshaw 2000; Williams et al. 2000). Despite significant impediments, such as fiscal constraints and the widespread shortage of nurses, the health care environment has never been so welcoming for dynamic nurse leaders and managers. This is because contemporary health care systems are no longer based upon hierarchical medical leadership but are more inclusive and interdisciplinary (Aiken et al. 2000). In order for nurses to function effectively in such environments, and, importantly, exert influence to optimise patient care, they need to appreciate the multiple factors that impact upon nursing practice and health care delivery. These factors are as diverse as the nature of nursing practice itself. In this chapter we explore the notion of clinical leadership within the current health care environment, and consider how individual nurses have engaged the system to develop nursing practice, improve quality of care and optimise patient outcomes.

HEALTH CARE IN CONTEXT

Contemporary health care systems are often portrayed as a system in crisis. Currently, the worldwide nurse staffing shortage continues to attract government and public comment (Buerhaus et al. 2000; Duffield & O’Brien-Pallas 2002; Jackson et al. 2001; McElmurry et al. 2000). Nursing as a predominantly female profession has experienced chronic staff retention issues over many years, and there is evidence of an ageing workforce (American Association of Colleges of Nursing Task Force 2002; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW] 2001), with the current average age of nurses in Australia being over 40 (Heath 2002). Governments continue various initiatives to entice ex-nurses back to the workforce, but a skills-set that includes applied problemsolving, flexibility, communication and management skills, is transferable to other work contexts and attractive to prospective employers. For example, ex-nurses work in the legal, government, commercial and academic sectors in roles that often have a health focus but are not directly related to nursing. Others thrive in non-health sector roles.

In Australia, two recent government inquiries into nursing and nursing education (Heath 2002; Senate Community Affairs Committee 2002) have recommended many initiatives to improve the critical status of nursing. Included in their recommendations were the establishment of a national nursing council to promote nursing leadership and build capacity through quality education and sustainable workforce initiatives, and increased collaborative partnerships, including additional clinical education funding and re-building of clinical education systems and infrastructure in hospitals and health services. Of particular relevance to the topic of managing nursing care delivery were identification of a national approach to the scope of practice, including nurse practitioners; examining whole-of health perspectives on health service planning; and examining work organisation and culture in health services (Heath 2002).

In 2001, a New Zealand review identified similar challenges facing nursing and the health care system there (Nursing Council of New Zealand 2001), including retention and recruitment issues (Grant-Mackie 2002; Prebble 2001). In response, the Ministry of Health and the Nursing Council launched the nurse practitioner (NP) career path to create highly skilled nurses and to encourage expert clinicians to stay and practise in New Zealand. This is a trend also seen in Australia, mainly to address the shortage of doctors in rural and remote areas, but also to meet the demands of nurses for recognition of advanced practice roles. More recently, a roll-out of NP positions has been occurring in metropolitan health services.

OPPORTUNITIES FOR CLINICAL NURSING LEADERS

Despite the difficulties outlined above, the Australian health system is relatively efficient and effective in operation, and continues to deliver care that has significantly improved patient outcomes and demonstrated examples of clinical excellence. One example is the decrease in mortality from coronary heart disease (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2002; Tonkin et al. 1999). While similar trends are demonstrated in other industrialised countries, internationally health care professionals are increasingly challenged to deliver health care in an equitable and accessible manner while dealing with issues of quality and safety (Institute of Medicine, Committee on Quality Health Care in America 1999; Meleis et al. 1995; Wilson et al. 1999). Further, the increasing trend towards globalisation means that we have to consider issues beyond our local environment in health care policy and delivery (Messias 2001).

Within this context, nurses now also have increasing opportunities to influence health care policy and practice. This new position of power is evidenced by representation on various state multidisciplinary committees and changes in practice following credible scientific research. Undeniably, significant barriers continue to exist, but these are not insurmountable (Heath 2002). Recognition that the greatest power base for nurses exists within the practice domain, with demonstration of clinical excellence and innovation are important factors in overcoming these barriers. For example, nurses in the management of chronic heart failure have demonstrated their ability to influence patient outcomes and policies through nurse-coordinated programs (Blue et al. 2001; McAlister et al. 2001).

As a consequence, leadership in the clinical domain is an important tool, and strategies to achieve this are discussed below. A clinical leader is a nurse who demonstrates the ability to influence and direct clinical practice (Lett 2002). This clinical leader also has a vision for the direction of nursing practice. This vision is informed by expert knowledge and analysis of the social, political and economic trends influencing health care. Fedoruk and Pincombe (2000) suggest that current and future nurse leaders need to let go of traditional managerial practices and behaviours to focus on achieving change management and process re-engineering. To achieve this goal, contemporary nursing leaders have to adopt a flexible, innovative and collaborative practice model. Pressures on the health care system—for example, financial pressures and increasing chronic disease burden—represent significant challenges for nurses. However, innovative models of care, increasing emphasis on independent nursing practice, and institution of clinical governance structures will likely serve nurses in addressing these challenges.

POLICY FRAMEWORKS FOR NURSING PRACTICE

In order to engage a system, direct change and assert leadership, it is important to appreciate what ‘drives’ this process. This observation is relevant at both a macro and a micro level of operation. Politics can be just as intriguing and complex within a hospital ward as at the bureaucratic or parliamentary levels. However, at all levels it is important to be aware of social, political and economic factors that direct health care systems (Borthwick & Galbally 2001). As members of society we have to remember that our part of the world is influenced by external factors and we need to be cognisant of these to understand the workings of our local environment.

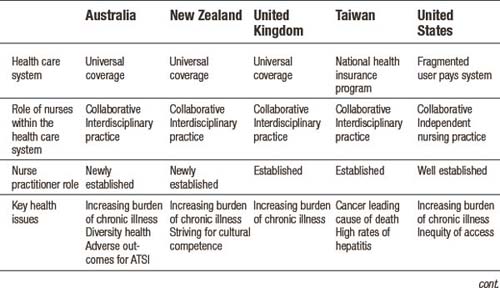

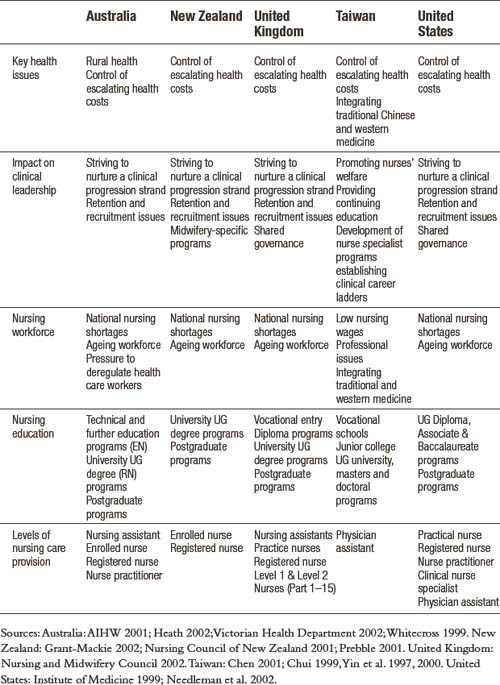

The working environment of nurses is influenced by the social, economic and political systems of the health care system. Table 19.1 compares the policy environments and roles of nurses in Australia, New Zealand, United Kingdom, Taiwan and the United States. In some instances, policy can be either a barrier or facilitator to clinical leadership. For example, policy environments in Australia do not favour independent nursing practice, whereas in the United States nurses can function as independent nursing practitioners (American Association of Colleges of Nursing Task Force 2002; Whitecross 1999). Internationally, health care professionals strive to ensure the delivery of safe and effective evidence-based care. Frameworks such as clinical and shared governance serve as a structure to achieve this goal. Clinical governance is a mechanism through which health care organisations are held accountable for continuously improving the quality of their services and ensuring high standards of care (O’May & Buchan 1999; Porter-O’Grady 1995, 2001; Prince 1997; Swage 2000). These concepts are discussed in greater depth in Chapter 22.

CHANGING MODELS OF CARE DELIVERY

A variety of care delivery models are used in health care—some relate to nursing only and are historic (Nelson 2000), while others are interdisciplinary and contemporary in focus (see Table 19.2). The changing health care environment—characterised by increasing short-stay surgery, decreasing lengths of stay and numbers of acute beds, combined with increasing patient acuity related to co-morbidities—requires vastly different models of care delivery from even a decade ago. Novel models of care are commonly developed in response to actual or perceived deficits in existing care delivery (Davidson & Elliott 2001).

Table 19.2 Common care delivery models

| Care delivery model | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Functional nursing | Ward-based care with allocation of specific clinical tasks to nursing staff (perhaps with different educational preparation) (e.g. physical care; medication administration) |

| Team nursing | Ward-based care where a small team of nurses (perhaps with different educational preparation) provide all care to a patient group Includes ‘care-pairs’ (RN plus EN/AIN) (Kenney 2001) |

| Patient allocation/total patient care | Ward-based care provided by an RN on a shift by shift basis to a number of patients (e.g. 1: 6 or 1: 8) |

| Primary nursing | Ward-based care with an RN assigned to patients for their entire admission period Plan of care is developed, implemented and evaluated by the ‘primary’ nurse, with ‘associate’ nurses continuing the plan in the absence of the ‘primary’ nurse |

| Care management / clinical pathways | Ward or hospital-based multidisciplinary co-ordinated patient care for a specific case type (e.g. patients with total hip replacement) Incorporated a ‘critical’ or ‘clinical path’ tool to ‘map’ and document care, including the sequence and timing of interventions |

| Case management | Hospital, outreach and / or community-based multi-disciplinary care that provides continuity of care for a specific case-type of patients (e.g. patients with heart failure) across the entire episode of care (beyond hospital admission) |

Sources: Crisp and Taylor 2001; Reiter-Tetel 2002; Urden and Walston 2001

Patients are admitted to acute care hospitals primarily for collaborative or independent nursing care, as many medical diagnostic and therapeutic procedures can now be conducted in ambulatory care settings, except in critical or emergent circumstances. However, efficient and effective care also requires continuity of patient management beyond the traditional hospital admission period to encompass the entire episode of care, particularly for those with continuing chronic disease. Coordinated care trials for patients with chronic and complex care needs, including integrated hospital and community care approaches (e.g. hospital in the home) are now being implemented and evaluated (Esterman & Ben-Tovim 2002).

The Commonwealth Government in Australia is currently funding Enhanced Primary Care Options—in particular, the development of collaborative health plans and review of patient outcomes through case conferencing—to enhance the management of chronic disease (Davis & Thurect 2001; NSW Health 2001; Whitecross 1999). In addition, issues of skill mix and different levels of nursing roles (registered nurse (RN), enrolled nurse, assistants in nursing) continue to be discussed because of budget constraints and staff shortages. However, one large US study using retrospective administrative data demonstrated a link between higher levels of RN care and shorter lengths of stay and a lower incidence of adverse events for patients (Needleman et al. 2002). Some health authorities are now mandating a specific nurse: patient ratio for acute ward areas in an attempt to maintain quality care (Steinbrook 2002; Victorian Health Department 2002), although any potential benefits are continuing to be debated professionally.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree