Johnson’s Behavioral System Model in Nursing Practice

Bonnie Holaday

Nursing is “an external regulatory force that acts to preserve the organization and integration of the patient’s behavior at an optimal level under those conditions in which the behavior constitutes a threat to physical or social health or in which illness is found.” The goal of nursing is to “restore, maintain or attain behavioral integrity, system stability, adjustment and adaptation, efficient and effective functioning of the system.

History and Background

The Johnson Behavioral System Model (JBSM) was conceived and developed by Dorothy Johnson while she was a professor of nursing at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). The process of developing this model began in the late 1950s as she examined the explicit goal of action of patient welfare that was unique to nursing. The task was to clarify nursing’s social mission from the perspective of a theoretically sound view of the client. The conceptual model that resulted was presented at Vanderbilt University in 1968 (Johnson, 1968). Since that time, other noteworthy presentations of the model have been offered (Auger, 1976; Dee, 1990; Derdiarian, 1990, 1993; Grubbs, 1974; Johnson, 1980, 1990). Johnson retired from UCLA in 1978, but she maintained her interest in “systems” through her hobby of shell collecting. She traveled extensively to collect shells and later donated them to a museum in Sanibel, Florida. Johnson died in February 1999. Johnson’s papers, documents, and letters, per her request, are available at the Eskind Biomedical Library Special Collections at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee.

The JBSM offers useful guidelines for nursing practice. Used in conjunction with the nursing process, it has provided a useful conceptual map to plan patient care. Poster, Dee, and Randell (1997) provided evidence supporting the efficacyof the JBSM as a tool for evaluating patient outcomes. Auger and Dee (1983) developed the UCLA Neuropsychiatric Institute and Hospital Classification System, based on the JBSM. This system was integrated with the nursing process and is used as a clinical measure of patient progress.

The work of Auger and Dee led to the development of behavioral indices, with each subsystem operationalized in terms of critical adaptive and maladaptive behaviors. The behaviors were ranked into categories according to their assumed level of adaptiveness. Nurse clinicians can rate each behavior for compliance by using an activity rating scale of 1 to 4. This scale provided a basis for allocating nursing resources at the UCLA Neuropsychiatric Institute (Dee & Randell, 1989).

Derdiarian used the JBSM to develop the Derdiarian Behavioral System Model (DBSM) instrument (Derdiarian, 1983, 1988; Derdiarian & Forsythe, 1983). The DBSM’s 22-category interview generated data pertaining to the major changes in the behavioral systems as a result of illness, as well as the positive or negative effects of these changes. Specifically, two types of subjective data were generated. This included the “set”-related variables (the variables that potentially predict or influence the patient’s usual behavior) and the behavior resulting from illness. Overall, research findings suggested that the DBSM instrument improved the focus, comprehensiveness, and quality of nursing assessment, diagnoses, interventions, and evaluation of outcomes of adult patients with cancer, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), and myocardial infarction (Derdiarian, 1983, 1988).

Other studies have also documented the utility of the JBSM for nursing practice. Holaday (1980) used the model to assess health status and to develop nursing interventions for children undergoing surgical procedures. Wang and Palmer (2010) used the model to conduct an analysis of the concept of women’s toileting behavior related to urinary elimination. Dee, van Servellen, and Brecht (1998) found that the JBSM could be used to derive meaningful conclusions about the impact of managed care on nursing care problems, and Coward and Wilkie (2000) demonstrated that the JBSM could be used to plan pain management for cancer patients. Colling, Owen, McCreedy, and colleagues (2003) planned a continence program for the frail elderly; Brinkley, Ricker, and Toumey (2007) used the model to examine esthetic knowing with a hospitalized obese patient; and Tamilarasi and Kanimozhi (2009) developed an intervention to improve the quality of life in breast cancer survivors.

Holaday’s work demonstrated identification of subsystem disorders, validated the notion of behavioral subsystems and their utility and usefulness in nursing practice, broadened the understanding of the role of “set,” and examined the relationship between sustenal imperatives and action (Holaday 1974, 1981, 1982, 1987; Holaday, Turner-Henson, & Swan, 1996). Derdiarian’s research demonstrated the factor-isolating and categorizing potential of the JBSM, validated the notion of behavioral subsystems, and provided empirical descriptions of central concepts in the theory (Derdiarian, 1983, 1988, 1990; Derdiarian & Forsythe, 1983). Meleis (2012) described the body of research related to nursing practice that the JBSM has generated and noted that it provided “significant developments in the conceptualization of the nursing client” (p. 280).

Overview of Johnson’s Behavioral System Model

Johnson’s model for nursing presents a view of the client as a living open system. The client is seen as a collection of behavioral subsystems that interrelate to form a behavioral system. Therefore, the behavior is the system, not the individual. This behavioral system is characterized by repetitive, regular, predictable, and goal-directed behaviors that always strive toward balance (Johnson, 1968).

Johnson (1968) proposed that the nursing client is a behavioral system with behaviors of interest to nursing and is organized into seven subsystems of behavior: achievement, affiliative, aggressive, dependence, eliminative, ingestive, and sexual. Nurses using the model believed that an additional area of behavior needed to be addressed (Auger, 1976; Derdiarian, 1990; Grubbs, 1974; Holaday, 1980). They added an eighth subsystem, restorative. Each subsystem has its own structure and function. Each subsystem comprises a goal based on a universal drive, set, choice, and action. Each of these four factors contributes to the observable activity of a person. Boxes 8-1 and 8-2 provide examples of how one might operationalize the function and structure of each subsystem. Grubbs (1980) provides excellent definitions of the concepts and terms used in the JBSM.

The goal of a subsystem is defined as “the ultimate consequence of behaviors” (Grubbs, 1974, p. 226). The basis for the goal is a universal drive, the existence of which is supported by existing theory or research. The goal of each subsystem is the same for all people when stated in general terms; however, variations among individuals occur and are based on the value placed on the goal and drive strength.

The second structural component is set, which is a tendency to act in a certain way in a given situation. Once they are developed, sets are relatively stable. Set formation is influenced by such societal norms and variables as culture, family, values, perception, and perseverative sets. The preparatory set describes one’s focus in a particular situation. The perseverative set, which implies persistence, refers to the habits one maintains. The flexibility or rigidity of the set varies with each person. Set plays a major role in determining the choices a person makes and actions eventually taken.

Choice refers to the alternate behaviors the person considers in any given situation. A person’s range of options may be broad or narrow. Options are influenced by such variables as age, gender, culture, and socioeconomic status.

The action is the observable behavior of the person. The actual behavior is restricted by the person’s size and abilities. Here the concern is the efficiency and effectiveness of the behavior in goal attainment.

Each of the subsystems also functions in a manner analogous to the physiology of biological systems (e.g., the urological system has both structural and functional components). The goal of the subsystem is a part of the structure. It is not entirely separate from its function.

For the eight subsystems to develop and maintain stability, each must have a constant supply of “functional requirements” or sustenal imperatives (Johnson, 1980, p. 212). The environment must supply the functional requirements or sustenal imperatives of protection from unwanted, disturbing stimuli; nurturancethrough giving input from the environment (e.g., food, caring, conditions that support growth and development); encouragement; and stimulation by experiences, events, and behavior that would “enhance growth and prevent stagnation” (Johnson, 1980, p. 212).

The subsystems maintain behavioral system balance as long as both the internal and the external environments are orderly, organized, and predictable and each of the subsystems’ goals is met. Behavioral system imbalance arises when structure, function, or functional regimen is disturbed. The JBSM differentiates fourdiagnostic classifications to delineate these disturbances: insufficiency, discrepancy, incompatibility, and dominance.

Nursing has the goal of maintaining, restoring, or attaining a balance or stability in the behavioral system or in the system as a whole. Nursing acts as an “external regulatory force” to modify or change the structure or to provide ways in which subsystems fulfill the structure’s functional requirement (Johnson, 1980, p. 214). Interventions directed toward restoring behavioral system balance are directed toward repairing damaged structural units, with the nurse temporarily imposing regulatory and control measures or helping the client develop or enhance his or her supplies of essential functional requirements.

Critical Thinking in Nursing Practice with Johnson’s Model

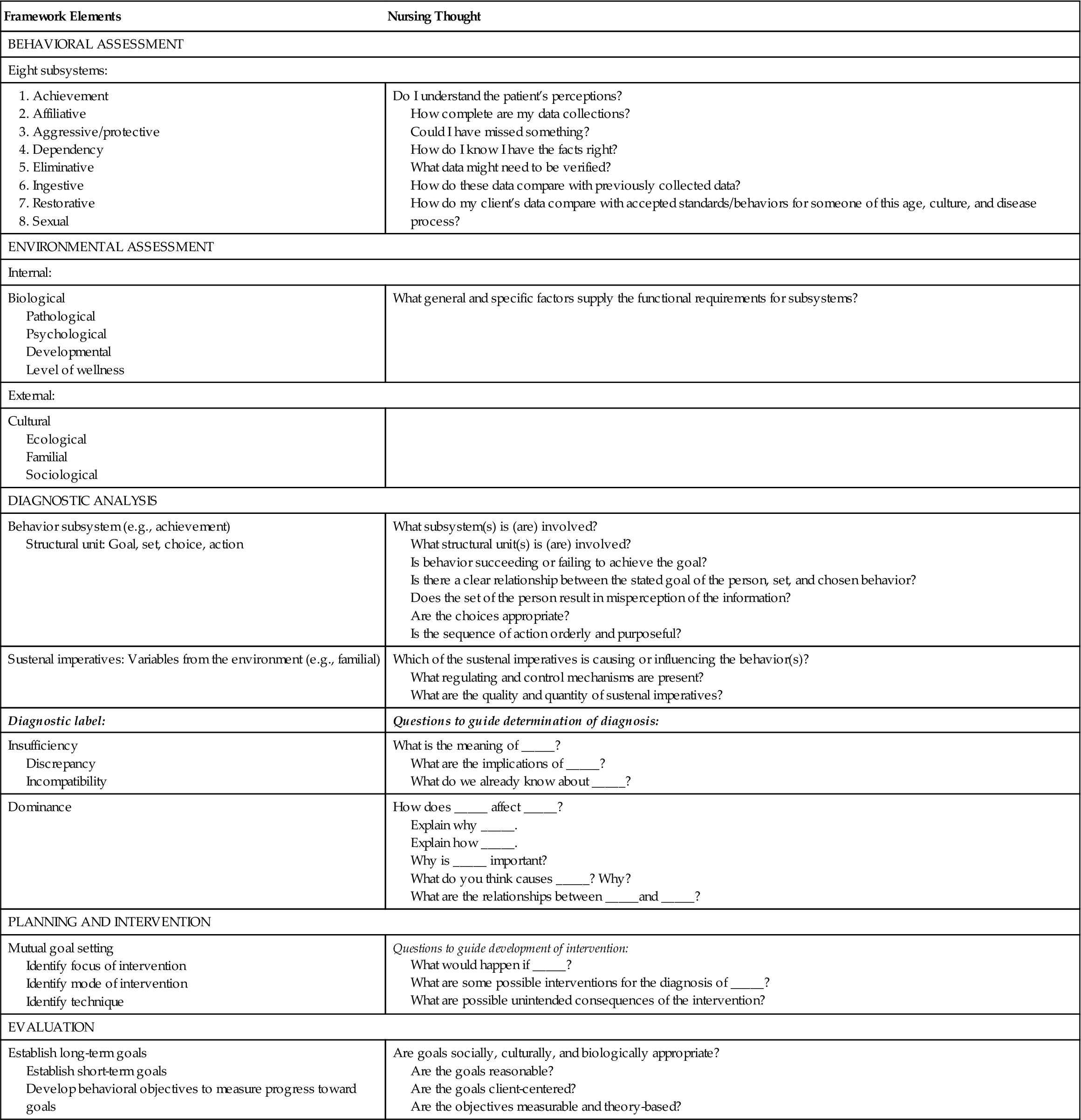

Making wise choices about nursing care requires the ability to think critically—that is, to analyze the available information, make inferences, draw logical conclusions, and critically evaluate all relevant elements, as well as the possible consequences of each nursing decision. From a constructivist perspective, individuals presented with complex information use their own existing knowledge and previous experience to help them make sense of the material. In particular, they make inferences, elaborate on the information by adding details, and generate relationships between and among the new information and the information already in memory. In short, they think critically about the new and old information (Paul & Elder, 2009). The JBSM provides information in a way that permits problem solving and care planning (Table 8-1).

TABLE 8-1

The Johnson Model and the Nursing Process

The focus of the process is to obtain knowledge of the client through interviews and observations of the patient and family to evaluate the present behavior in terms of past patterns, to determine the effect of the present illness or perceived health threat and/or hospitalization on behavioral patterns, and to establish the maximum possible level of health toward which an individual can strive. The behavioral systems’ analysis approach provides a comprehensive framework in which various types of data can be organized into a cohesive structure.

The assessment gathers specific knowledge regarding the structure and function of the eight subsystems (behavioral assessment) and those general and specific factors that supply the subsystems’ functional requirements/sustenal imperatives (environmental assessment). Interview questions in both areas need to be theory-based. For example, Piagetian theory can be used to develop questions to assess a child’s ability to express knowledge about illness—eliminative subsystem (Holaday, 1980).

Once the interview has been completed, data analysis (diagnostic analysis; see Table 8-1) is necessary to identify patterns of behavior that are adaptive and functional for the client as well as those that are maladaptive and indicate behavioral systems’ imbalance. One component of the analysis seeks to determine congruency among all structural units. Congruency is expressed as stable, patterned behavior, whereas discrepancy among the components is expressed as unstable and disorganized behavior. The second component examines how the functional requirements/sustenal imperatives influence subsystem behavior. For example, how does family interaction style affect the client’s affiliative subsystem? The latter analysis is critical because it plays an important role in determining how the nurse needs to function as an “external regulator” (Johnson, 1980, p. 214).

The nursing diagnosis is a summary of the results for the analysis and describes the current level of behavioral system function. It serves as a guide for intervention planning by the nursing team. The overall objective of the nursing intervention is to establish regularities in the client’s behavior to meet the goal of each subsystem. The focus on the intervention will be either on a structural part of the subsystem or on the supply of sustenal imperatives/functional requirements.

Identifying goals is essential for evaluating client outcomes and for professional nursing care. To evaluate, the nurse must first predict expected client outcomes. This helps ensure a purposeful, predictable course of client responses. To evaluate effectively, the nurse sets both long-term and short-term goals and behavioral objectives that will indicate progress toward achieving these goals.

Concept mapping is also an effective strategy to combine with use of a nursing theory such as the JBSM (Daley, 1996). A concept map is a graphic or pictorial arrangement of key concepts that address specific subject matter such as behavioral system imbalance. Concept maps are organized with the most important or central concept at the top of or in the center of the paper (Figure 8-1). Related information or issues are to the side or underneath the main topic. There is no right or wrong way to design a concept map. It may be a flowchart or a diagram or even shaped like a heart if the issue were congenital heart disease. The purpose of the concept map is to develop critical thinking skills and problem-solving abilities (All, Huycke, & Fischer, 2003; Ferrario, 2004).