2

Introduction to community settings, services and roles

• To describe the settings where services are provided in the community

• To discuss community nursing roles

• To introduce the student to the roles of the wider primary health and social care team

Care settings in the community

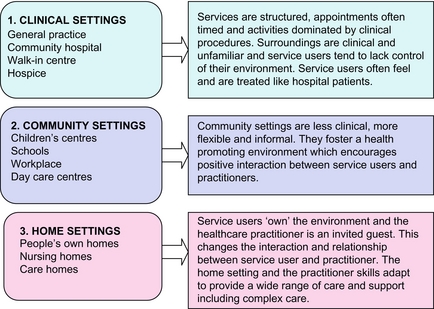

In Chapter 1, we described the setting for primary, secondary and community care as being part of the community. One way of helping to understand how services are organised and delivered in primary and community care and to overcome some of the complexity, is to group together those that have something in common. Figure 2.1 shows how settings can be grouped into three categories: clinical, community and home settings.

Clinical settings in the community

Community hospital

• Intermediate managed care provided by GPs

• Out-of-hours and emergency triaging services

• Outpatient and specialist clinics with visiting consultants

• Pre-admission and routine testing

• Treatment for patients who cannot be cared for at home but who do not require the specialist care provided by a district hospital

• Convalescence or step down care

The term community hospital is often associated with the traditional model of a small local hospital in a small town providing an inpatient service which is scaled down from the large acute and specialist hospital miles away in the city. It is probably more relevant these days to refer to community-based centres which may or may not include inpatient beds, depending on the identified needs of the area. Not only do community hospitals or community-based centres have an important role to play in rural areas, urban areas can also benefit from locally based services, and there is potential to make a real difference to inner city areas with significant health needs.

The following are three examples of community-based centres in urban settings:

1. A ‘24-bed urban community-based facility’ offers GPs an alternative to admission to the acute sector for medically stable older people. It provides nurse-led, GP-supported care with a focus on the promotion of independence through rehabilitation and co-ordinated health and social care.

2. A ‘community treatment centre’ provides healthcare for local people in the centre of their community. As well as providing a range of diagnostic services and outpatient clinics, including paediatrics, it also offers rehabilitation assessment for older people and services, such as dietetics, physiotherapy, midwifery and community dentistry. Co-located services include social work, psychiatric nursing, voluntary services and school nursing. There are no inpatient beds.

3. A ‘general practice urgent care centre’ is a healthcare services facility commissioned by a teaching Primary Care Trust. The centre, operated by an independent provider of health and social care services, is located within a multicultural inner city community. The centre is open every day from 8 am and 8 pm and offers a range of comprehensive healthcare services to registered patients and a walk-in service for the treatment of minor injuries and illnesses, without having to make an appointment. Services include doctor’s certificates, repeat prescriptions, treatment of minor injuries and illnesses, follow-up care, emergency contraception, vaccinations and immunisations, contraceptive services, cervical screening services, child health surveillance services, maternity services, chronic disease management (e.g. asthma, diabetes), lifestyle advice and smoking cessation.

Nurse-led services

Laurent et al (2005) undertook a review of the substitution of doctors by nurses in primary care. Although there was limited research evidence, the review indicated that appropriately trained nurses can produce care of the same high quality and achieve equally good health outcomes for patients as doctors and at a lower cost. In many cases, it is not necessary to see a GP, so in areas where it is hard to recruit doctors or in some rural, remote and inner city areas where GP services are more difficult for people to access, nurse-led clinics and services offer a more accessible alternative. Not surprisingly, nurse-led services in primary care have flourished since the 1990s and tend to be either specialised and defined by the activities that are performed (there are some examples in Table 2.1) or more generalist in nature, such as nurse-led walk-in centres or minor injuries units.

Table 2.1

Examples of nurse-led clinics in the community

| Asthma and COPD | Minor injuries |

| Family planning | Minor illness |

| Diabetes | Childhood immunisation |

| Cervical smears | Heart disease and stroke |

| Well person clinic | Travel health |

| Smoking cessation | Leg ulcer clinic |

Community settings

Sure Start children’s centres

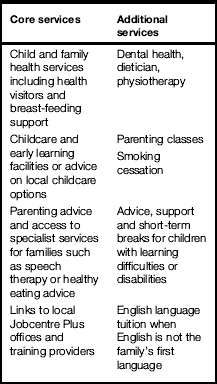

Sure Start is a government initiative introduced in England in 1998. Sure Start children’s centres aim to provide a ‘one stop shop’ for children and their parents bringing together the different support agencies which offer a range of services and advice from pregnancy to school age. Each children’s centre is developed to meet the needs of the local community and, although core services must be offered at all centres, additional services vary according to local needs. Examples of core and additional services are shown in Table 2.2.

Day care centres for adults

• Access to a variety of health and care services such as the district nurse, podiatrist, social worker, optician and care assistants to help with bathing

• Employment schemes for people with learning disabilities or people with mental health problems can offer employment opportunities to people who may otherwise have difficulty finding work

• Rehabilitation and enablement – the opportunity to re-learn skills that have been lost through illness or disability or to learn new skills to cope with changing circumstances

• Social interaction – meeting and mixing with others, sharing stories and experiences, making friends

• Stimulation – leisure activities such as painting sessions, singing, chess, bingo, mobile library, cookery, internet

In many areas, lunch clubs based in local facilities provide a hot meal and offer social interaction and support for older people. They are often run by volunteers and funded by members and local voluntary groups.

Community pharmacies

They can be found in some of the most deprived communities, which offer very little else in terms of health care. Based in the heart of the community, community pharmacists are probably the most easily accessible of all healthcare providers and are consequently well placed to focus on the most hard-to-reach and vulnerable families in their community. (See more about the services that are offered in community pharmacies later in the chapter.)

The workplace

In large organisations, most occupational health services are led by either an occupational health nurse, or an occupational health doctor, with other members of the team providing consultancy advice as needed. The day-to-day running of the occupational health service is often undertaken by a manager who is an occupational health nurse. Other members of the multidisciplinary occupational health team include physiotherapists; ergonomists, who specialise in the design of equipment and the workplace environment, toxicologists and clerical staff. Table 2.3 shows the types of services offered within occupational health.

Table 2.3

| Pre-employment screening | Occupational health assessment is often used to ensure that the person can safely work in an environment that is suitable for them or so that the employer can consider appropriate adjustments to help reduce the risk of health and safety issues developing over time. In some jobs the law or regulation requires individuals to be assessed before they start work |

| Fitness assessment | People with health problems affecting their fitness for work may be assessed and regularly monitored and the appropriate support made available |

| Support | Occupational health services aim to support employees when they become ill by following best practice on rehabilitation and making reasonable adjustments for people with a disability |

| Address specific health issues | Specific health issues include, stress, back pain and repetitive strain injury or work-related upper limb disorders, bullying, discrimination and harassment by other staff, managers or members of the public, such as patients or customers, manage harmful substances safely, environmental issues such as vibration, temperature, light and noise |

| Health improvement | Health promoting activities may focus on the specific needs of the workplace, e.g. smoking, drug and alcohol use, disease prevention and control, e.g. coronary heart disease and obesity, mental health and wellbeing and work–life balance. In addition, travel advice, vaccinations and immunisations and fitness programmes may be provided |

| Health surveillance | This includes regular screening as required by health and safety regulations in addition to those statutory screening when working with lead, ionising radiation and asbestos |

| Absence reviews | Independent assessment of people who have been absent from work usually for prolonged periods of time help to identify possible solutions. Rehabilitation programmes, counselling and advice to both management and the individual can support a staged return to work |

| Provide information and advice | Managers, employees and trade unions often require information about the workplace practices and policies of the organisation. Occupational health teams also advise organisations on the development and implementation of policy in-line with regulatory and legal requirements and provide training for staff, e.g. moving and handling |

| Treatment centres | Large organisations can find it more cost-effective to provide on site services such as physiotherapy, dental care and counselling services |

Home and residential settings

A research study looking at the environmental housing conditions on the health and wellbeing of children conducted by the Social Care Institute for Excellence (SCIE), in 2005, reported the following key messages:

• More than 1 million children live in housing in England that it considered sub-standard or unfit to live in

• On the whole, the research indicates that there is an association between homes with visible damp or mould and the prevalence of asthma or respiratory problems among children

• Dampness and mould has also been found to be associated with exacerbated symptoms among children with asthma or wheezing illness

• Poor-quality housing can have an adverse effect on children’s psychological wellbeing

• Parents and children both complain of the social stigma of living in bad housing

• Overcrowding and cooking with gas may cause respiratory infections in pre-term infants

• Interventions such as installing or improving heating systems, has been found to be effective in alleviating the potentially adverse effects of damp on the health of children SCIE (2005).

Nursing home and residential care home

There are differences in the ways in which the four regulators are structured and discharge their duties. However, their overall aim is the same: to ensure the safety and wellbeing of vulnerable people who use services in local authorities, businesses, charities and voluntary organisations in the community. Regulation, inspection, review and support are methods used to encourage compliance with care standards and promote continuous quality improvement.

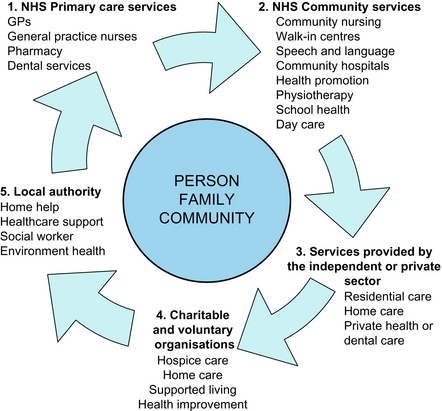

Service provision

Services differ in their characteristics because of the people they serve and also the type of provider organisation. Different solutions suit different service users, even within the same locality, and so reflect a personalised approach to care. The analysis of relevant and accurate information from local and national sources enables services to be planned at a strategic level. However, a local health needs assessment or a community profile builds up a picture of the health needs of the community in a particular area, often down to the level of the practice population and from there, services are adapted to meet the local needs. (Chapters 3 and 5 discuss health needs and assessment and community profiling in more detail.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree