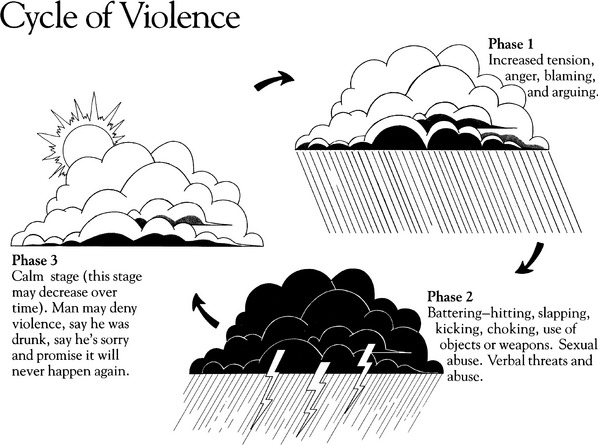

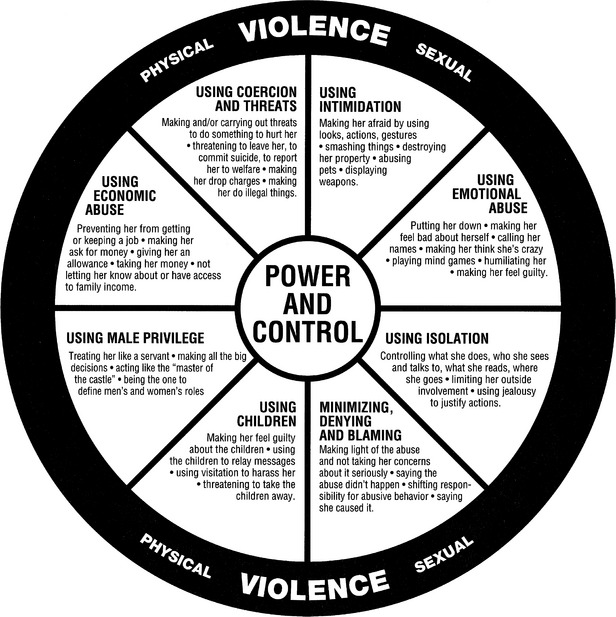

CHAPTER 18 1 Discuss the prevalence of violence against women in the United States. 2 Describe the cycle of violence, and differentiate between the various phases. 3 List behaviors of the abuser in each of the phases of the violence cycle. 4 Identify the types of physical injuries that battered women sustain, and discuss how pregnancy alters the body parts targeted by the abuser. 5 Discuss the psychological injuries that battered women sustain. 6 Identify how cultural differences and socioeconomic status influence the prevalence of intimate partner violence (IPV) in the United States. 7 Describe common characteristics of men who are abusers and of women who are victims of abuse. 8 Recognize key elements to be included in the assessment of all women and additional data to be collected from a woman at high risk for abuse. 9 List physical, psychological, and nonverbal findings in a woman that are consistent with abuse in her relationship. 10 Describe and discuss primary, secondary, and tertiary intervention strategies used to provide care to abused women. 11 Design a plan of care that maximizes the abused woman’s ability to protect herself and her children and to make informed decisions on which she can act. 12 Identify resources and referrals that are available for victims of IPV. A Health care providers need to understand the types of violence that women experience in order to provide informed care. 1. IPV, family violence, battering, and partner or spousal abuse all describe the physical, sexual, or psychological harm caused by a current or former partner or spouse (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2008). IPV includes some or all of the following (Saltzman, Fanslow, McMahon, & Shelley, 2002): B Health care providers interact with women experiencing IPV on a daily basis, often without being aware of it. 1. The true incidence of IPV perpetrated against women in the United States is unknown because a large amount of it remains undetected and unreported. a. The mandatory reporting mechanism for IPV involving an adult woman only exists in five states, whereas nearly all states require reporting of IPV if it occurs concurrently with a crime (Phelan, 2007). b. IPV is, however, considered a felony in all states. c. Domestic violence accounts for more injuries to women than car accidents, muggings, and rapes combined (CDC, 2008). d. One third of women seen in emergency rooms report current physical abuse or battering (Kramer, Lorenzon, & Mueller, 2004). e. Up to 31% of women using primary care clinics report one or more types of abuse within the past year (Kramer et al, 2004). f. IPV has been recognized as a health problem of major proportions in the United States and Canada. (1) In the United States, estimates are that 1.9 million women are assaulted annually by an intimate partner (Tjadin & Thoennes, 2000). (2) In Canada, 21% of women have experienced IPV within the past year (Romans, Forte, Cohen, Du Mont, & Hyman, 2007). (3) Each year, more than 500,000 women injured as a result of IPV require medical treatment (Tjaden & Thoennes, 2000). (4) Women in same-sex relationships also experience IPV (Hassouneh & Glass, 2008). 1. Pioneer research about abuse of women was conducted by Lenore Walker in 1979 (Walker, 1982). a. Her research gave detailed accounts of women’s abuse and how the abuse progressed in a relationship. b. She discovered a cyclic pattern of progression of abuse in female-male relationships that is now identified as the cycle of violence (Figure 18-1). 2. Abusive behavior, especially battering, exhibits a three-phase cyclic pattern. Although this illustration focuses on male abuser and female victim, females can also be abusers. a. Phase 1 is characterized as a period of increasing tension in the abuser, marked by the following behaviors: (1) Increased anger directed toward the woman (2) Increased blame attributed to the woman (3) Escalated arguments with the woman (4) Woman may feel like she has to keep her partner or spouse calm. b. Phase 2 is the acute battering incident in which the batterer demonstrates an uncontrollable discharge of the built-up tension. (1) This phase can last from a few minutes to hours, sometimes even several days. (2) Physical battering behaviors are as follows: (i) Throwing the woman across a room or up against a wall (k) Mutilating with objects such as knives, broken glass, razor blades, and tools (l) Burning with objects such as an iron, scalding liquids, cigarettes, or caustic substances (3) Psychological battering behaviors are as follows: (d) Destroying things of value to the woman (e) Destroying her personal belongings (f) Throwing her things out the door or window (j) Remarks intended to decrease her self-esteem (k) Remarks to make her doubt her worth, her abilities, and her decision making (l) Taking away “privileges” normally afforded to adults and conditionally granting permission to temporarily get them back (m) Isolating her from family, friends, and adult contacts (4) The batterer frequently justifies his battering behaviors by stating that the purpose is to teach the woman a lesson. (5) Most injuries are to the woman’s face, arms, and buttocks; during pregnancy, injuries may be frequently seen around the abdomen. c. Phase 3 is the calm stage; also called the honeymoon stage. (1) The batterer is usually remorseful and profusely apologetic. (2) He may shower her with gifts. (3) He solemnly promises that the abuse will never happen again. (4) He may deny or minimize the violence that occurred in phase 2. (5) He promises the woman that everything will be different from this time on. d. The behaviors exhibited in phase 3 of the cycle of violence offer the woman hope and are a powerful and positive reinforcement for staying in the relationship. 1. Physical injuries to an abused woman may include the following: b. Hematomas, particularly periorbital e. Lacerations, particularly around the mouth, lips, eyes, and other parts of the face f. Perforation of the tympanic membrane g. Scalp lacerations, hematomas, tufts of hair missing 2. Other physical problems occur in response to repeated abuse. Abused women report an increased prevalence of: 3. Psychological injuries to a battered woman may include the following: E Cultural and socioeconomic differences 1. Violence against women cuts across all socioeconomic and ethnic lines (Rodriguez, 1994). 2. Poverty and oppression are significant factors in the prevalence of violent behavior; the following factors have been associated with a higher incidence of IPV: 3. The meaning of violence in various cultures is difficult to determine because cultures vary in their perceptions and definitions of abuse (Hanrahan, Campbell, & Ulrich, 1993; Mattson & Rodriguez, 1999). 4. Minority women, in general, are less likely to use shelters and more likely to use the health care system combined with support from family and friends (Noel & Yam, 1992). The culture is viewed as an oppressed group, and access to health care can be very limited (Rynerson, 2007; Suarez & Ramirez, 1999). 5. Cultural influences on awareness of abuse (1) No convincing evidence has been found that greater violence against women exists among this group (Hattery, 2008); however, women are more likely to report violence when it does occur. (2) Men who live in an impoverished neighborhood are three times as likely to commit IPV as compared with their counterparts who do not live in impoverished areas (Cunradi, Caetano, Clark, & Schafer, 2000). (3) IPV may be triggered by threats to the men’s masculinity, such as unemployment, difficulty keeping a job, and racial domination (Smith, 2008). (4) The risk of abuse may be high when the woman has more education than the man if he views this as a threat to his masculinity (Smith, 2008). (5) Women fear that disclosing abuse will bring disgrace or increased discrimination to the entire community (Campbell et al, 2006). (1) Families are more egalitarian in their decision making than in past years, especially when women work outside the home or have higher education levels (Klevens et al, 2007). (2) Generally, sex roles are clearly defined. (3) Mexican-American women perceive fewer types of behavior as being abusive (Torrés, 1991). (4) Women typically share their experiences of abuse with their families and friends; although responses are variable, families most often prefer to remain uninvolved beyond providing tangible aid or confronting the abuser (Klevens et al, 2007). (5) Through religious and cultural images, Hispanic women often believe abuse is their “lot in life to suffer”; they are defined by their family roles, and their primary obligation is to preserve the family at all costs (Flores-Ortiz, 1993; Mattson & Rodriguez, 1999). (6) Acculturation is an important influence on IPV for men and women, although the relationship differs. Men with low acculturation levels experience high stress and increased involvement in IPV, whereas women who are highly acculturated have an increased risk for IPV (Caetano, Ramisetty-Mikler, Caetano Vaeth, & Harris, 2007). (7) The culture is viewed as an oppressed group, and access to health care can be very limited (Rynerson, 2007; Suarez & Ramirez, 1999). (1) Rates of IPV among Native American women are more than double the rates among African American, white, and Asian women (Rennison, 2001). (2) Native American women may experience more forms of potentially lethal violence than women from all other ethnic and racial groups (Tjaden & Thoennes, 2000). (3) Few studies seek to understand IPV across more than one tribe or region, failing to take into account the tremendous heterogeneity across more than 500 U.S. tribes, many of whom have their own culture, traditions, lifestyles, and language (Bohn, 2003). (4) Native Americans’ 400-year history of oppression, violence, poverty, limited resources, isolation, and disenfranchisement may contribute to the violence within Native American families (Bohn, 2003). 1. The progression of aggression continuum (O’Leary, 1993) a. Verbal aggression, such as yelling and name calling b. Followed by lesser forms of physical aggression, such as pushing and slapping c. Followed by true violent behavior, such as punching and beating 2. Intergenerational transmission of violence a. Abuser and woman generally learn about IPV in their family of origin. (1) Witnessing violence in childhood triples one’s risk of becoming a batterer in adulthood (Ehrensaft & Cohen, 2003). (2) Most abusers report childhood memories of harsh physical punishment as a means of discipline (Rynerson, 2007). b. Childhood sexual abuse increases the risk of physical and sexual abuse in adulthood, thereby perpetuating the cycle of intergenerational abuse (Noll, Horowitz, Bonanno, Trickett, & Putnam, 2003). c. An acceptable awareness is—as a child in a violent family—that people who love each other can be violent. d. Children who witness parental violence are especially susceptible to psychological and social consequences with lifelong effect, including: (1) Posttraumatic stress disorders (3) Attention-deficit hyperactive disorder (4) Irritability, aggression, and quickness to anger (5) Boys are more likely to act out; girls are more likely to internalize (Ruiz & Mattson, 2003). e. Some research suggests that exposure of the neonate and very young children to violence alters central nervous system development, predisposing the child to more impulsive, reactive, and violent behavior (Ruiz & Mattson, 2003). 3. Family structure can shape the attitude toward IPV. a. Gender inequality with ascribed gender roles b. Power and violence serve to maintain a patriarchal view that gives authority to men. 4. Possible causes of aggression in an abuser (O’Leary, 1993)

Intimate Partner Violence

INTRODUCTION

Intimate Partner Violence

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access