Introduction

The previous two chapters helped to set the scene for the book by mapping the emergence of teamwork and describing a range of current developments. In this chapter we aim to explore key concepts and issues related to interprofessional teamwork to understand its conceptual foundations. In doing so, we review and critique the literature describing teamwork characteristics, team typologies and the constituent elements that contribute to team effectiveness. We also argue for a contingency approach to teamwork – one which values other forms of interprofessional work such as collaboration, coordination and networking. Finally, we explore the applicability of teamwork approaches that have been developed in other settings (e.g. crew resource management) for health and social care settings.

Describing and characterising teamwork

Interprofessional teams come into existence to ensure that health and social care professions can complete a care task (or combination of tasks) that they could not achieve so effectively on their own. Indeed, as we outlined in Chapter 1, the increasing complexity of organising, coordinating and delivering care demands that professionals regularly come together, share information and reach agreement in their work. However, as we go on to discuss, not all groups of practitioners who come together to collaborate work as teams.

Traditionally, the literature has employed terms such as ‘group’ and ‘team’ interchangeably (e.g. Douglas, 1983; Adair, 1986). The rationale behind this standpoint is that interactions which occur within groups and teams are similar. As Douglas (1983, p. 1) noted:

Teams are co-operative groups in that they are called into being to perform a task, a task that cannot be performed by an individual.

More recently, authors have moved away from thinking that groups and teams are interchangeable concepts. While the former is seen as a ‘looser’ arrangement of individuals who periodically interact, the latter is regarded as something more. Sundstrom et al. (1990), for instance, have emphasised three core elements that characterise teams. First, individuals should hold a shared identity of themselves as ‘team members’. Second, each team member should have their own individual role so as to ensure that members do not duplicate work. Third, teams should share a collective agreement around how they work together.

Similarly, Pritchard (1995) has outlined four distinctive features that help define a team. While one feature – that team members should have an understanding of all members’ role and function – is similar to one of the elements proposed by Sundstrom et al., Pritchard also identifies a number of additional features: team members should share a common purpose for their work; members pool their skills and knowledge; and team members are able to work interdependently with one another.

Mohrman et al.’s (1995) description shares a number of similar elements, including that team members share goals; are interdependent in their accomplishment of tasks and goals; and that they work in an integrated fashion with one another. In addition, they emphasise that a team needs to be mutually and collectively accountable for meeting goals and producing outputs. Cohen and Bailey (1997) outline similar features, but importantly also note that teams are regarded (by their members and others) as discrete social entities.

In their approach, Headrick et al. (1998) suggest a range of characteristics which describe interprofessional teamwork. These include that team goals and objectives are stated, restated and reinforced; that member roles and tasks are clear and known; that the atmosphere in the team is respectful; that responsibility for team success is shared; that there is clarity regarding authority and accountability; that the team decision-making and communication processes are clear; and that information is regularly shared.

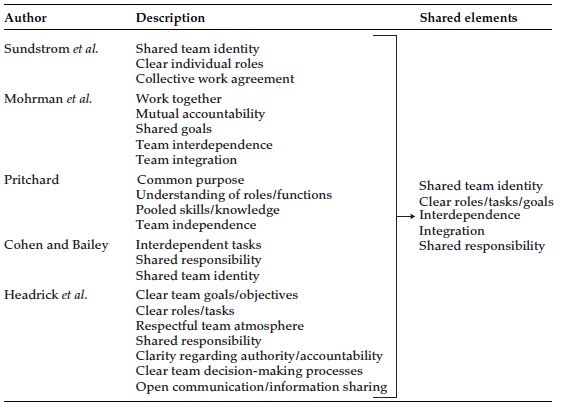

Teamwork characteristics put forward by these authors overlap substantially. Table 3.1 summarises and synthesises these descriptions of teams to identify key elements which comprise the essence of teamwork.

As illustrated in Table 3.1, our synthesis produced over 20 descriptors of teamwork. From this starting point we have identified five common elements of teamwork: shared identity, clear roles/tasks/goals, interdependence of team members, integration of work and shared responsibility.

Team tasks

While these five elements help define the essence of a team, for us, they overlook team tasks and how, in particular their predictability, urgency and complexity can affect teamwork. In clinical settings such as operating theatres, intensive care and trauma care where team tasks are typically unpredictable, urgent and complex professionals need to have a close interdependence, integration and shared responsibility. In contrast, in settings such as primary care or outpatient clinics, where team tasks are generally more predictable and less urgent, issues such as interdependence and integration of members’ may be equally important, but less urgent, and are thus generally organised in a less structured fashion. Box 3.1 provides two examples – the operating room and the outpatient clinic – of how predictability, urgency and complexity can have an influence on the ability of interprofessional teams to function.

Box 3.1 The influence of team tasks on teamwork.

The operating room. Time pressures and divergent workflow patterns within this context can minimise opportunities for teamwork, necessitating tight prior planning for interprofessional collaboration and placing a high demand on clarity of roles and team communication. Work in the operating room involves critical sources of variability. The patient’s arrival can be emergent and not scheduled. Further, the surgical process, the patient condition and results of the intervention can be unpredictable.

The arthritis outpatient clinic. Patients and their families arrive at the clinic at scheduled times. During the appointment there can be a discussion between patient, family and different professionals about their arthritis care. Either at or after the appointment, an interprofessional review of treatment may take place during which plans for the future, which may include referral to other services and a date for a return visit. A consistent group of professionals may share care, often asynchronously.

As Box 3.1 indicates, due to the unpredictable, urgent and complex nature of work in the operating room, there is a clear need for an effective time-critical interprofessional team response, which contrasts with more predictable and routinised nature of the outpatient clinic. We return, later in this chapter, to explore how team tasks relate to the shared elements outlined in Table 3.1.

Teamwork authors have also provided a range of different typologies for varying types of teams. In general, these suggest that teams can be placed on a spectrum from ‘poor teams’ (e.g. those who do not work in an integrated fashion and interact infrequently) to ‘good teams’ (those who share an integrated approach and interact on a regular basis). Below we summarise a number of the more well-known typologies before offering a critique.

Bruce (1980) devised a model of teamwork that includes three types of teams. The first type is a nominal team in which members do not share a common goal; may have little idea of each other’s roles; where communication is poor; and where there is generally little interaction between members. The second is a convenient team in which a few members share a common goal; there is some understanding of members’ roles and responsibilities; but where there is only limited interaction and communication between members. The third is a committed team in which all members share a common goal; roles and responsibilities between team members are well understood; and where there is good communication and regular interaction between members.

Katzenbach and Smith (1993) developed a slightly different model that contains five types of team:

- Working groups in which members hold some shared information and undertake some team activities, but where there is no joint responsibility or clear definition of team roles

- Pseudo teams in which members are labelled as a ‘team’ but, in reality, have little shared responsibility or coordination of their teamwork

- Potential teams in which members are beginning to work in a collaborative manner but have few of the factors needed for effective teamwork, such as the sharing of common team goals

- Real teams in which members share common goals and share some accountability

- High performance teams in which members all hold a clear understanding of their roles, all share common team goals and, in addition, encourage members’ personal development.

More recently, Drinka and Clark (2000) have distinguished between the following types of multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary health care teams. The first is an ad hoc task group who work together to solve task-related problems and then disbands. The second is a formal multidisciplinary work group, an interprofessional group that works together, but individuals work more independently than collectively. The third is an interactive interdisciplinary team. This final type is seen as having integrated diagnoses, team goals for patients and interdependent membership.

As noted above, these three typologies consider the level of integration of teams. Other authors, such as Jelphs and Dickinson (2008), have focused on the extent to which individuals from different disciplinary backgrounds collaborate within teams. In their work they have distinguished between multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary teams. They see the first type of team as one in which practitioners work in parallel, or side-by-side with each other but with little interaction; the second type of team in which practitioners work together in an interactive fashion; and the final type as one in which members work is integrated and ‘transcend[s] their separate, conceptual and methodological orientations’ (p. 13). The authors go on to note that this final type of team can be regarded as the highest form of teamwork.

While these typologies offer some useful ways of understanding the nature of different forms of teamwork, they also have limitations. For example, Katzenbach and Smith have compounded team performance and team type, as their descriptions of ‘potential’, ‘real’ and ‘high performance’ essentially describe team performance rather than different categories of teamwork. In contrast, Drinka and Clark have provided typologies which offer descriptions of different forms of disciplinarity within teams/groups. Furthermore, most typologies presented above have confused different types of ‘teamwork’ with different forms of interprofessional work such as collaboration and coordination. For example, Bruce’s description of a nominal team arguably operates in the manner which is more like a network – a loosely connected group who interact on an episodic basis.

In general, these typologies provide a rather normative and linear understanding of teamwork – where teams may ‘progress’ from a state of poor functioning to a higher level of performance. In practice, interprofessional teamwork is more complex, and will vary on each of the key elements listed in Table 3.1. Indeed, there seems to be an assumption that teams operating at the ‘lower ends’ of these varying typologies (e.g. convenient teams, pseudo teams) need to strive to reach their upper ends to function like ‘committed teams’ or ‘real teams’. Such an assumption overlooks the pragmatics of real world teamwork.

Given the limitations of these typologies, we argue that a contingency approach is more useful. This approach takes into account the elements listed in Table 3.1: shared team identity, clear roles/goals, interdependence, integration, shared responsibility as well as our notion of team tasks. Each of these elements can be viewed as a continuum along which a particular team can be placed, for example, from having a weak team identity to having a strong, shared team identity. Teams may vary in their location along each of these dimensions independently a team that has a strong shared team identity may, at the same time, have more loosely integrated work practices. This approach does not view teams and teamworking as moving along a linear, hierarchical spectrum from ‘weak’ to ‘strong’. Rather, it suggests a more complex and nuanced picture of teamwork in which teams need to be matched to the purpose they are intended to serve as well as their local needs. For some purposes, greater shared responsibility among team members may be important while for other purposes it may not be so. In designing and organising teams, it may be useful to consider what configuration of each of these elements would best address or match the local goals that the team is being established to fulfil.

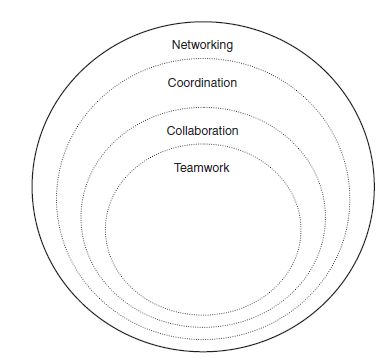

Given this approach, in which teams think about their purpose and also how they can respond to local needs, we argue that teamwork is only one of the forms of interprofessional work which could be considered. Other forms are collaboration, coordination and networking. Depending on local need, these forms of interprofessional work may be more effective than a teamwork approach. Figure 3.1 outlines how we have distinguished between four main types of interprofessional work.

As Figure 3.1 shows, we have located interprofessional teamwork in the centre because it can be viewed as the most ‘focused’ of activities with high levels of interdependence, integration and shared responsibility. The other approaches to interprofessional work – collaboration, coordination and networking – are increasingly broader activities with reduced levels of interdependence, integration and so on.

While this typology is tentative in nature, and needs empirical testing before we can be confident of its applicability to real life, it begins to indicate how different types of interprofessional work can be considered contingent on the nature of responding to local need. Below we provide further details of these different forms of interprofessional work.

As noted above, teamwork encompasses a number of core elements including, but not restricted to, shared team identity, clarity, interdependence, integration, shared responsibility and team tasks which are generally unpredictable, urgent and complex. Examples of this type of interprofessional work include intensive care teams and emergency department/room teams (e.g. Piquette et al., 2009a, 2009b). Box 3.2 provides an illustration of this type of interprofessional work.

Box 3.2 An example of interprofessional teamwork.

Based in an emergency department, a small team of nurses, physicians, pharmacists and respiratory therapists work together to meet the needs of patients, who arrive unpredictably with a range of acute conditions which need immediate attention. The team functions in an integrative fashion, with each member interacting and communicating to perform their profession-specific tasks in a clear and timely manner. Team members often come together to debrief and reflect when they encounter a complex clinical episode. Over their time together, trust and mutual support has grown between members, who often socialise with one another in the evenings. Consequently, the members feel a strong sense of membership with their team.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree