INTERPROFESSIONAL COLLABORATION

Collaborative work between health care professionals has been assigned a number of terms as health care has evolved over the decades, including interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary, interprofessional, multiprofessional, and transdisciplinary (Leathard, 2003; Mitchell, 2005; Nancarrow et al., 2013). All of these models of collaboration in health care are associated with teamwork. However, some distinctions have been made among the terms. The terms interprofessional and multiprofessional have a narrower focus than interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary (Atwal & Caldwell, 2002; McCallin, 2001). Interprofessional and multiprofessional are generally defined as consisting entirely of professionals from different disciplines, whereas interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary includes professional and nonprofessional staff (Nancarrow et al., 2013). Some authors go on to explain that interprofessional denotes collaboration, whereas multiprofessional and multidisciplinary do not (Goodman & Clemow, 2010). Transdisciplinary collaboration has been used to delineate the development of a new conceptual framework that diminishes the barriers to interprofessional work (Nowotney, 2005; Weaver, 2008). Transdisciplinary work diminishes traditional differences between disciplines and uses a holistic approach to collaborative work, with the result being more than the sum of the individual disciplines’ contributions. New approaches, knowledge, products, or even new disciplines may result from transdisciplinary work (Weaver, 2008).

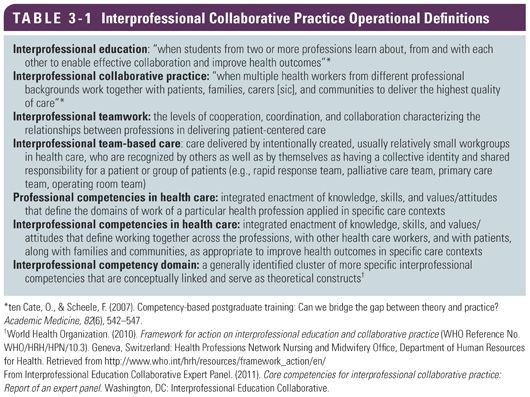

To further explain interprofessional practice, a number of related interprofessional operational definitions have been developed to provide the team members with a common language from which to develop a high-performing team. These terms include interprofessionality, interprofessional education, interprofessional collaborative practice, interprofessional teamwork, interprofessional team-based care, professional competencies in health, interprofessional competencies in health care, interprofessional competencies, and interprofessional competency domain (Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel, 2011) (Table 3-1). Interprofessionality is the fundamental concept used to explain the process that must occur for the patient’s needs to be met. Characteristics of interprofessionality include continuous interaction, knowledge sharing to address education and care issues, patient participation, an ethical code of conduct, and an integrated collaborative workflow (D’Amour & Oandasan, 2005).

INTERPROFESSIONAL PRACTICE MODELS

INTERPROFESSIONAL PRACTICE MODELS

A number of interprofessional practice models have been developed. Although models may differ in their composition and roles, most interprofessional practice frameworks include a set of values and/or core competencies critical to their model. For example, an early model described by Ponte, Gross, Winer, Connaughton, and Hassinger (2007) consisted of only three team members: the nurse, physician, and hospital administrator. Yet, many of the concepts included in this model such as collaboration, decision making, patient- and family-centered care, patient safety, and priority setting are still considered essential to the effectiveness of the interprofessional practice model today (Ponte et al., 2007). In addition, earlier models of interprofessional teams embraced a style of interdisciplinary leadership that included empowerment of the individual in a nonhierarchical, nonthreatening environment and a partnership in which team members learn from each other and collectively become more effective than the individual contributions of each health care professional (Dietrich et al., 2010; Richardson & Storr, 2010). These principles are considered key to the work of interprofessional teamwork today as well.

A number of interprofessional practice models have been developed. Although models may differ in their composition and roles, most interprofessional practice frameworks include a set of values and/or core competencies critical to their model. For example, an early model described by Ponte, Gross, Winer, Connaughton, and Hassinger (2007) consisted of only three team members: the nurse, physician, and hospital administrator. Yet, many of the concepts included in this model such as collaboration, decision making, patient- and family-centered care, patient safety, and priority setting are still considered essential to the effectiveness of the interprofessional practice model today (Ponte et al., 2007). In addition, earlier models of interprofessional teams embraced a style of interdisciplinary leadership that included empowerment of the individual in a nonhierarchical, nonthreatening environment and a partnership in which team members learn from each other and collectively become more effective than the individual contributions of each health care professional (Dietrich et al., 2010; Richardson & Storr, 2010). These principles are considered key to the work of interprofessional teamwork today as well.

In 2009, Hammick, Freeth, Copperman, and Goodsman stated that the core values of being interprofessional are respect, confidence, engagement with others, caring disposition, approachable attitude, and willingness to share. Competencies for being an interprofessional team member included (1) knowledge related to the work of others and teamwork; (2) collaborative and communicative skills and application of interprofessional education principles; and (3) appreciation and respect for others’ collaboration, views, values, and ideas (Hammick et al., 2009). More recently, national and international interprofessional panels have developed formal frameworks calling for the urgent development of interprofessional collaborative practice and have detailed competency domains delineating specific attributes (Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel, 2011; World Health Organization [WHO], 2010). WHO (2010) defines the domains of interprofessional practice (and learning) as teamwork, roles and responsibilities, communication, learning and critical reflection, recognizing the needs of patients and developing a relationship with them, and ethical practice. Similarly in 2011, the Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel—composed of the American Association of Colleges of Nursing, American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine, American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy, American Dental Education Association, Association of American Medical Colleges, and the Association of Schools of Public Health—established competencies in four domains: values and ethics, roles and responsibilities, communication, and teams and teamwork.

More recently, Ash and Miller (2014) attributed successful interprofessional collaboration to many of the same characteristics described earlier, including shared purpose, shared decision making, reciprocal trust, team member recognition and value, high-level performance, role and responsibility clarity, collaborative work culture, strong leadership, effective communication, and conflict resolution. In addition, they added the concepts of emotional intelligence, transformational leadership, differentiation of leadership and management, and the role of change agent, continuous reflective learning, and the patient and family as members of the interprofessional team.

Emotional intelligence is one’s awareness of the role emotion plays in relationships and how emotions can be used in a positive manner to facilitate communications and motivate others. Transformational leaders empower others to achieve shared goals using coaching and mentoring to inspire others toward a desired state (Institute of Medicine, 2011). The focus of leadership involves the development of relationships through modeling, inspiring, challenging, enabling others, and encouragement. In contrast, management concepts emphasize using resources to meet organizational goals rather than a concerted focus on the development of the team and its individual members to maximize outcomes. The interprofessional team must view themselves as change agents who continuously learn and reflect on that learning to adapt and change as needed to meet the team’s goals. The team’s inclusion of the patient and family as a member of the team, with full disclosure of the patient’s condition, provision of meaningful and consistent patient and family education, and facilitation of an active patient and family voice in decision making, are conducive to patient- and family-centered care (Institute of Medicine, 2011). Patient- and family-centered care empowers the patient and family to maximally benefit from the work of the team with greater understanding of their disease and how they can make a difference in their recovery. Patient- and family-centered care also results in greater patient, family, and team satisfaction (Ash & Miller, 2014). The interprofessional practice models, described earlier and still evolving, are essential to ensure stroke care of the highest quality.

INTERPROFESSIONAL STROKE TEAMS ACROSS THE CONTINUUM OF CARE

INTERPROFESSIONAL STROKE TEAMS ACROSS THE CONTINUUM OF CARE

The teamwork that occurs in stroke care depends on a number of factors, including the patient’s clinical presentation, the type of stroke, treatment options, and the extent of disabilities. The roles of the interprofessional health team members may extend beyond a single acuity level and transition point. Stroke care often requires multiple interprofessional teams that provide a continuum of care within and across institutions without disruption to minimize risk of deterioration and poor outcomes. See Table 10-2 for possible interprofessional team members and roles.

The levels of care for stroke patients include prehospital, telestroke, and emergency department (ED) care; acute care; critical care; electronic intensive care unit (ICU); progressive care; rehabilitation; skilled nursing facility care; long-term care; nursing home care; home care; secondary prevention; and palliative care. The goals of primary and secondary prevention include identification of risk factors and effective management of modifiable risk factors (see Chapter 1). Critical to effective management of modifiable risk factors is patient and family education and access to care to assist the patient with compliance (Goldstein et al., 2011).

Prehospital, telestroke, and ED personnel have shared roles, including identification of stroke, field response, transport, evaluation, emergent care, consultation, and referral for additional interventions and management (Audebert, 2006; Gorelick, Gorelick, & Sloan, 2008; Stradling, 2009). Depending on the emergency medical system within a geographic area, an emergency medical technician may be the first responder at the scene but may ask for additional support from paramedics with advanced life support training for the stroke patient with life-threatening cardiopulmonary disease. This will enable provision of airway protection and resuscitation including medication administration at the scene. After the initial workup and management at the first hospital, if the level of care needed by the patient is not available at the first hospital, the prehospital providers, including flight nurses and paramedics, may transport the patient from the original hospital without higher level stroke management expertise to a primary or comprehensive stroke center by ground or air.

EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT ADMISSION

EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT ADMISSION

In the ED, much of the interprofessional team work is performed by physicians, advanced practice nurses, physician assistants, nurses, and respiratory therapists. Medical specialties include emergency medicine, neurology, neurosurgery, neuroradiology neurointerventionists, neurointensivists, hospitalists, physiatry, and other specialties that may be needed as consultants to make recommendations about the stroke patient’s care. For example, risk factors that have contributed to the stroke may be problematic in managing the stroke, such as cardiac disease and diabetes mellitus. The stroke itself may have resulted in complications such as respiratory compromise, the inability to maintain a patent airway, ineffective breathing, aspiration, or a stunned myocardium in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage.

In the ED, much of the interprofessional team work is performed by physicians, advanced practice nurses, physician assistants, nurses, and respiratory therapists. Medical specialties include emergency medicine, neurology, neurosurgery, neuroradiology neurointerventionists, neurointensivists, hospitalists, physiatry, and other specialties that may be needed as consultants to make recommendations about the stroke patient’s care. For example, risk factors that have contributed to the stroke may be problematic in managing the stroke, such as cardiac disease and diabetes mellitus. The stroke itself may have resulted in complications such as respiratory compromise, the inability to maintain a patent airway, ineffective breathing, aspiration, or a stunned myocardium in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Once the patient has arrived in the ED, a stroke code may be called. However, the stroke neurologist or neurosurgeon may have already been informed about the incoming patient and established a plan that includes continued stabilization and rapid neurological assessment including imaging, laboratory analysis, and determination of definitive treatment with attention to time-sensitive interventions. More than one facility may be involved such as the receiving hospital with limited resources and a primary or comprehensive stroke center. The stroke neurologist at the primary or comprehensive stroke center may review imaging and clinical presentation with the physician at the receiving hospital. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for intravenous (IV) recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA) may be reviewed and a plan of care determined. For example, the IV rtPA may be started at the receiving hospital followed by a transfer to the primary or comprehensive stroke center. The pharmacist may be directly involved with rtPA dosing and blood pressure management strategies. Neurosurgery may be consulted for a hemorrhagic stroke or increased intracranial pressure from a large territory stroke. Interventional neuroradiology may also be consulted for endovascular therapies such as aneurysmal stenting and coiling (Summers et al., 2009).

ED nurses are responsible for assessing and monitoring the patient with attention to airway, breathing, and circulation; neurological status; responsiveness related to therapies; and blood pressure control. Neither physicians nor nurses can work in isolation to maximize the impact of their efforts without the involvement of other disciplines to accomplish mutual goals for the patient.

The respiratory therapist will assess the respiratory system, provide pulmonary hygiene, manage oxygen therapy, or collaborate with the team regarding intubation and mechanical ventilation management. If the patient is awake and stable, a nurse-directed swallow screen may be performed to screen for safety from aspiration. If it is determined that the patient is at low risk for aspiration, oral medications can be safely administered. In the acute phase of stroke, respiratory therapists work to reduce risk of hypoxia, aspiration, and ventilator-associated pneumonia post stroke.

The respiratory therapist will assess the respiratory system, provide pulmonary hygiene, manage oxygen therapy, or collaborate with the team regarding intubation and mechanical ventilation management. If the patient is awake and stable, a nurse-directed swallow screen may be performed to screen for safety from aspiration. If it is determined that the patient is at low risk for aspiration, oral medications can be safely administered. In the acute phase of stroke, respiratory therapists work to reduce risk of hypoxia, aspiration, and ventilator-associated pneumonia post stroke.

Although patient and family education begins in the ED and can be undertaken by any team members, the education is very focused on the stroke and immediate treatment decisions. Palliative care may be consulted as needed for comfort or end-of-life considerations as the patient’s condition warrants (Creutzfeldt, Holloway, & Walker, 2012).

ADMISSION TO THE ACUTE CARE FACILITY

ADMISSION TO THE ACUTE CARE FACILITY

Upon admission to the critical care, acute care, or stroke unit in an acute care hospital, more team members become involved in patient care. An additional diagnostic workup and consultation by neurosurgery, interventional neuroradiology, or interventional neuroradiology may be required. A decompressive craniectomy may be indicated in a large territory ischemic stroke or hemorrhagic stroke. Insertion of an external ventricular drainage device may be indicated for subarachnoid hemorrhage or intraparenchymal stroke and may be performed at the bedside in critical care or in the operating room (OR).

Upon admission to the critical care, acute care, or stroke unit in an acute care hospital, more team members become involved in patient care. An additional diagnostic workup and consultation by neurosurgery, interventional neuroradiology, or interventional neuroradiology may be required. A decompressive craniectomy may be indicated in a large territory ischemic stroke or hemorrhagic stroke. Insertion of an external ventricular drainage device may be indicated for subarachnoid hemorrhage or intraparenchymal stroke and may be performed at the bedside in critical care or in the operating room (OR).

Depending on the severity of the stroke and the level of consciousness, an initial evaluation by rehabilitation therapies may occur early on admission or postponed until the patient’s condition stabilizes. If the patient did not pass the nurse swallow screen, the speech therapist will evaluate swallowing and also assess the patient’s communication and cognitive functions.  Respiratory therapy will continue to assess and intervene for airway and breathing issues, both directly related to the acute stroke and any prestroke pulmonary issues such as obstructive sleep apnea, a risk factor for stroke, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Physical and occupational therapy will evaluate extremity strength, tone, and coordination and provide recommendations and interventions around such rehabilitation strategies as protective positioning, range of motion, mobilization, and working with perceptual deficits. Once tone returns to the affected extremities, occupational and physical therapists will evaluate and assist in the management of spasticity as needed (Miller et al., 2010). The rehabilitation physician may be consulted to assess abilities and recommend management post stroke but prior to rehabilitation.

Respiratory therapy will continue to assess and intervene for airway and breathing issues, both directly related to the acute stroke and any prestroke pulmonary issues such as obstructive sleep apnea, a risk factor for stroke, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Physical and occupational therapy will evaluate extremity strength, tone, and coordination and provide recommendations and interventions around such rehabilitation strategies as protective positioning, range of motion, mobilization, and working with perceptual deficits. Once tone returns to the affected extremities, occupational and physical therapists will evaluate and assist in the management of spasticity as needed (Miller et al., 2010). The rehabilitation physician may be consulted to assess abilities and recommend management post stroke but prior to rehabilitation.

In critical care, the patient’s medical management may be directed by a neurocritical care intensivist or a general critical care intensivist. Advanced practice nurses and physician’s assistants may also direct the care of the stroke patient. The staff nurse assesses, plans, intervenes, and evaluates the patient holistically with attention to physiologic, cognitive, and psychosocial needs. Respiratory therapy may not only continue to provide the management initiated in the ED but also work toward discontinuation of mechanical ventilation and intubation as the patient’s condition allows. The pharmacist will review the patient’s prestroke medication profile and current pharmacological needs and reconcile those needs while assessing for drug interactions or adverse effects.

In critical care, the patient’s medical management may be directed by a neurocritical care intensivist or a general critical care intensivist. Advanced practice nurses and physician’s assistants may also direct the care of the stroke patient. The staff nurse assesses, plans, intervenes, and evaluates the patient holistically with attention to physiologic, cognitive, and psychosocial needs. Respiratory therapy may not only continue to provide the management initiated in the ED but also work toward discontinuation of mechanical ventilation and intubation as the patient’s condition allows. The pharmacist will review the patient’s prestroke medication profile and current pharmacological needs and reconcile those needs while assessing for drug interactions or adverse effects.

Early in critical care (or acute care), the dietitian will assess the patient’s nutritional status and develop a plan for nutritional support, depending on the patient’s ability for oral intake, or recommend enteral feedings. Parental nutrition is rarely required. Later in critical care or acute care phase, the dietitian may counsel patients about dietary risk reduction strategies for hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, or other recommended dietary modifications.

Early in critical care (or acute care), the dietitian will assess the patient’s nutritional status and develop a plan for nutritional support, depending on the patient’s ability for oral intake, or recommend enteral feedings. Parental nutrition is rarely required. Later in critical care or acute care phase, the dietitian may counsel patients about dietary risk reduction strategies for hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, or other recommended dietary modifications.  The rehabilitation therapists begin their work in the critical or acute care setting with an initial patient assessment followed by progressive activity as soon as the patient’s condition has stabilized (Cell, Hassan, Marquardt, Breslow, & Rosenfeld, 2001; Connolly et al., 2012; Jauch et al., 2013; Morgenstern et al., 2010). Rehabilitation therapists include speech, occupational, physical, and recreational therapists. The focus of the speech therapist is swallowing, cognition (including attention and memory), and communication (including speech and language). Speech therapists, also referred to as speech and language pathologists, address perceptual disorders, such as apraxia, along with occupational and physical therapists (Miller et al., 2010). Occupational and physical therapists work with the patient to recover lost motor and sensory abilities especially in relationship to performing activities of daily living (ADLs). Compensatory measures are taught for residual deficits to optimize independence in ADLs. Assistive devices may be incorporated into the patient’s plan of care. Occupational therapists focus on ADLs, preventive/corrective splinting and positioning, and adaptation of the home and workplace environments to accommodate disabilities (Langhorne, Bernhardt, & Kwakkel, 2011; Milller et al., 2010; National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, 2013; Pinter & Brainin, 2012).

The rehabilitation therapists begin their work in the critical or acute care setting with an initial patient assessment followed by progressive activity as soon as the patient’s condition has stabilized (Cell, Hassan, Marquardt, Breslow, & Rosenfeld, 2001; Connolly et al., 2012; Jauch et al., 2013; Morgenstern et al., 2010). Rehabilitation therapists include speech, occupational, physical, and recreational therapists. The focus of the speech therapist is swallowing, cognition (including attention and memory), and communication (including speech and language). Speech therapists, also referred to as speech and language pathologists, address perceptual disorders, such as apraxia, along with occupational and physical therapists (Miller et al., 2010). Occupational and physical therapists work with the patient to recover lost motor and sensory abilities especially in relationship to performing activities of daily living (ADLs). Compensatory measures are taught for residual deficits to optimize independence in ADLs. Assistive devices may be incorporated into the patient’s plan of care. Occupational therapists focus on ADLs, preventive/corrective splinting and positioning, and adaptation of the home and workplace environments to accommodate disabilities (Langhorne, Bernhardt, & Kwakkel, 2011; Milller et al., 2010; National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, 2013; Pinter & Brainin, 2012).

Transitions between settings in the hospital are critical, as transitions are often associated with missed communication and errors. Attention to detail and effective handoffs between critical care and acute care teams are essential to prevent deterioration, new complications, and return to critical care. If the patient was originally admitted to critical care but has been advanced to acute care, increased mobilization such as up to chair and walking, depending on the patient’s neurological status, now becomes an immediate focus of care.  Previous team members such as the physician, nurse, pharmacist, respiratory therapist, dietician, and speech, occupational, and physical therapists will continue to move the patient toward the highest level of functional recovery possible and minimize risk of complications related to impaired mobility and hospitalization including venous thromboembolism, bowel and bladder incontinence, skin breakdown, falls, and delirium. Patient and family education, particularly regarding risk factors and secondary prevention, will be emphasized, including comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease, pulmonary disease, and diabetes; medications for blood pressure and hyperlipidemia; and antiplatelet/anticoagulant medications. Education around other interventions may be taught to family members as well, including participation in therapies. A hospitalist or the stroke neurologist or neurosurgeon-led team may direct care in acute care (Summers et al., 2009).

Previous team members such as the physician, nurse, pharmacist, respiratory therapist, dietician, and speech, occupational, and physical therapists will continue to move the patient toward the highest level of functional recovery possible and minimize risk of complications related to impaired mobility and hospitalization including venous thromboembolism, bowel and bladder incontinence, skin breakdown, falls, and delirium. Patient and family education, particularly regarding risk factors and secondary prevention, will be emphasized, including comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease, pulmonary disease, and diabetes; medications for blood pressure and hyperlipidemia; and antiplatelet/anticoagulant medications. Education around other interventions may be taught to family members as well, including participation in therapies. A hospitalist or the stroke neurologist or neurosurgeon-led team may direct care in acute care (Summers et al., 2009).

If the patient is discharged from an acute care hospital and admitted to an in-hospital rehabilitation facility, the focus will, more than ever, be on the functional recovery and teaching both the patient and family what they need to know to achieve the highest functionality and quality of life possible.  The team approach is never more evident than in rehabilitation with the involvement of the physiatrist; rehabilitation nurse; speech, occupational, and physical therapists; recreational therapist; and neuropsychologist as needed, if not consulted, in critical or acute care. Recreational therapists may work with the stroke patient to incorporate diversional activities into their recovery program. Recreational therapists assist in the recovery of previously learned skills and the acquisition of new skills with a focus on community reintegration (Miller et al., 2010; Williams et al., 2007). See Chapter 10 for a discussion of rehabilitation.

The team approach is never more evident than in rehabilitation with the involvement of the physiatrist; rehabilitation nurse; speech, occupational, and physical therapists; recreational therapist; and neuropsychologist as needed, if not consulted, in critical or acute care. Recreational therapists may work with the stroke patient to incorporate diversional activities into their recovery program. Recreational therapists assist in the recovery of previously learned skills and the acquisition of new skills with a focus on community reintegration (Miller et al., 2010; Williams et al., 2007). See Chapter 10 for a discussion of rehabilitation.

Discharge planning will be coordinated by social services or another health care professional, such as a nurse in the role of a case manager or discharge facilitator. If not consulted previously, the neuropsychologist will assess for poststroke depression and coping skills.

Discharge planning will be coordinated by social services or another health care professional, such as a nurse in the role of a case manager or discharge facilitator. If not consulted previously, the neuropsychologist will assess for poststroke depression and coping skills.

MATCHING THE NEXT LEVELS OF CARE WITH PATIENT NEEDS

MATCHING THE NEXT LEVELS OF CARE WITH PATIENT NEEDS

Following acute stroke care, the next level of care will depend on the individual’s functional recovery at the time of discharge.  The team will assess if the patient’s current condition at discharge best enables him or her to meet the goals of care that are fostered in rehabilitation, skilled nursing, long-term health care facility, nursing home, or home with or without outpatient rehabilitation or home health visits (Langhorne et al., 2011). Failure of the interprofessional stroke care team(s) to recognize the best placement of the stroke patient at this time may result in physical, cognitive, and emotional deterioration; failure to facilitate recovery; and wasted resources. Regardless of the discharge disposition, the focus of continued care is secondary stroke prevention to minimize recurrent stroke.

The team will assess if the patient’s current condition at discharge best enables him or her to meet the goals of care that are fostered in rehabilitation, skilled nursing, long-term health care facility, nursing home, or home with or without outpatient rehabilitation or home health visits (Langhorne et al., 2011). Failure of the interprofessional stroke care team(s) to recognize the best placement of the stroke patient at this time may result in physical, cognitive, and emotional deterioration; failure to facilitate recovery; and wasted resources. Regardless of the discharge disposition, the focus of continued care is secondary stroke prevention to minimize recurrent stroke.

In the event that the patient is unable to participate in at least 3 hours of therapy and requires more direct nursing care, the patient may be discharged to a skilled nursing facility, nursing home, long-term care facility, or, possibly, home. At a skilled nursing facility, the patient may receive additional rehabilitation therapies to improve his or her readiness for rehabilitation. Regardless, the goal, depending on the patient’s condition, will be to maintain the highest quality of life possible and minimize complications.

Neuropsychologists can evaluate cognitive deficits and assist with the management of cognitive and neurobehavioral dysfunction, including providing counseling for the patient and family regarding poststroke depression (Miller et al., 2010). Social workers and rehabilitation counselors also support the patient’s recovery from stroke by identifying resources, facilitating coping, and assisting the patient’s return to a meaningful life. The vocational rehabilitation counselor’s focus is vocational counseling and placement, whereas the social worker’s goal is less focused on returning the patient to work but rather in supporting the patient with the ability to function at the highest level in society (Miller et al., 2010).

Neuropsychologists can evaluate cognitive deficits and assist with the management of cognitive and neurobehavioral dysfunction, including providing counseling for the patient and family regarding poststroke depression (Miller et al., 2010). Social workers and rehabilitation counselors also support the patient’s recovery from stroke by identifying resources, facilitating coping, and assisting the patient’s return to a meaningful life. The vocational rehabilitation counselor’s focus is vocational counseling and placement, whereas the social worker’s goal is less focused on returning the patient to work but rather in supporting the patient with the ability to function at the highest level in society (Miller et al., 2010).  Social workers may initially assess the patient’s living situation while the patient is in critical care or acute care. However, they often continue to educate, inform, and counsel patients and their family as well as advocate for them beyond the acute phase of their stroke in rehabilitation, nursing home, long-term and skilled nursing facilities, and the community settings.

Social workers may initially assess the patient’s living situation while the patient is in critical care or acute care. However, they often continue to educate, inform, and counsel patients and their family as well as advocate for them beyond the acute phase of their stroke in rehabilitation, nursing home, long-term and skilled nursing facilities, and the community settings.

Finally, palliative care may provide an environment to assist the patient and family with end-of-life decisions. Palliative care has a broader scope in symptom detection and management to improve quality of life (Creutzfeldt et al., 2012).  Palliative care specialists provide expert recommendations regarding symptom management and goal setting and may be consulted anywhere along the continuum of stroke care (Holloway et al., 2014). Specific examples of the palliative care specialist’s role in the care of the stroke patient include the management of refractory pain, dyspnea, agitation, and emotional distress as well as assisting in decision making regarding long-term nutrition and mechanical ventilation (Holloway et al., 2014).

Palliative care specialists provide expert recommendations regarding symptom management and goal setting and may be consulted anywhere along the continuum of stroke care (Holloway et al., 2014). Specific examples of the palliative care specialist’s role in the care of the stroke patient include the management of refractory pain, dyspnea, agitation, and emotional distress as well as assisting in decision making regarding long-term nutrition and mechanical ventilation (Holloway et al., 2014).

STRATEGIES FOR BUILDING AND SUSTAINING INTERPROFESSIONAL TEAM

STRATEGIES FOR BUILDING AND SUSTAINING INTERPROFESSIONAL TEAM

Successful interprofessional collaboration in stroke care depends on a number of team-building and team-sustaining strategies and may be facilitated by implementation of formal team-building initiatives and positively reinforced by current regulatory requirements in stroke care. A number of characteristics have been assigned to successful interprofessional teams, including effective communication; mutual respect and understanding; trust; an appropriate combination of expertise and experience; a mutual goal orientation toward quality outcomes; efficient and effective resources; individual and group flexibility; clear purpose, role, and vision; leadership; a team culture; education and training opportunities; a positive presence; individual strengths; and value of the group work for the individual as well as the group as a whole (Clark, 2009; Molyneux, 2001; Nancarrow et al., 2013; Weaver, 2008). Individually and collectively, these characteristics are in alignment with successful interprofessional collaboration in stroke care. Formal programs, also referred to as tool kits, may be implemented to facilitate development of these attributes within stroke teams.

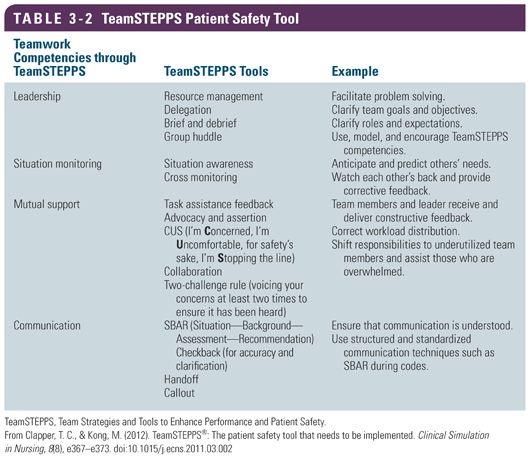

One program that may enhance interprofessional collaboration of stroke teams is Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety (TeamSTEPPS) Program, an evidence-based program developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and the U.S. Department of Defense, to train teams in four major competencies including communication, leadership, situation or performance monitoring, and mutual support. Originally developed for use in aviation-related issues, this course includes both didactic and simulation work for the health care participants (AHRQ, 2014; Clancy, 2007; Clapper & Kong, 2012; Stead et al., 2009). TeamSTEPPS tools to support development of the competencies include resource management; delegation, briefs, debriefs, and small group huddles; situation awareness; cross monitoring of other’s needs; and providing feedback to correct the situation.

The basic TeamSTEPPS framework and concepts are congruent with and complementary to the interprofessional model. Key elements of TeamSTEPPS include the knowledge, skills, and actions (KSA) associated with teamwork, leadership, situation monitoring, mutual support, and communication (AHRQ, 2014) (Table 3-2). Effective teams are defined as work units with shared roles and responsibilities, strong leadership, goals, plans, and priorities. High-performing teams are interactive, dynamic, interdependent, and adaptive. Leaders of teams keep the team focused yet allow the team members, individually and collectively, to flourish. Effective leaders facilitate team actions, model exemplary behavior, communicate effectively, monitor situations, delegate, resolve conflict, and manage resources. The TeamSTEPPS model includes the use of such tools as briefs for planning work, huddles for updating the team on emergent situations, and debriefs to analyze events, change plans, and promote learning (AHRQ, 2014).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree