CHAPTER 5 Interprofessional education

sharing the wealth

USING THEORIES TO DRIVE EDUCATION METHODS

Example: When setting an IPE learning task, the task and learning outcome should be tailored to specific interprofessional practice goals. Low-relevance IPE activities tend to be more passive and decontextualised from applied settings (e.g. combining different professions in a lecture format). High-relevance activities occur when students undertake learning tasks that are more representative of future professional situations. These include problem-based learning tutorials, using clinical simulation and fostering a team-based collaborative approach to patient assessment and management in the clinical setting. Cross-discipline supervision, such as a nurse educator supervising medical and/or physiotherapy students, is a further example of a teaching method that models interprofessional understanding and practice.

Introduction

This chapter addresses some important questions associated with understanding and implementing interprofessional education (IPE) in clinical and other applied settings. The chapter is divided into three sections to assist readers to review this broad topic. Section 1 covers the history and provides some definitions of IPE, including some rationales for those definitions. In this section, questions are asked such as: Why is IPE needed? What are some defining features of IPE programs? What evidence is there that they ‘work’? In Section 2 some examples of research are presented. They focus on ways to judge the effectiveness of interprofessional programs. A typology of IPE outcomes is applied to analyse some of the reported effects of two Australian case studies. In Section 3 some of the perceived and other barriers to implementing IPE are discussed. This also includes some suggested responses to these challenges, and describes enabling factors that have been useful in building successful IPE programs in the clinical or fieldwork context.

Section 1 History and definitions

A very brief history of IPE

Abdel-Halim (2006) cites Arabic documents from 1000 years ago that demonstrate the benefits of teamwork in the interests of the patient. More recently, two decades ago the World Health Organization (WHO 1988) formally recognised the need for greater interprofessional education and practice:

Interestingly, the WHO is currently reviewing global progress towards the goals outlined in its 1988 report (Yan et al 2007). The impetus for the review and the reason for increased attention to IPE are the worldwide shortage and maldistribution of healthcare workers, and the need for better collaboration to maximise the effectiveness of scarce human and other resources.

While some core themes in IPE seem to be timeless, the challenge for current educators and practitioners is to bring IPE in from the margins of their respective curricula. This means a systematic and explicit focus on key elements of IPE in the design, delivery, assessment, research and evaluation associated with health and social care programs. Of course, for this to happen there must also be substantial policy shifts along with corresponding funding and resourcing arrangements (Stone 2007).

What is IPE?

Agreeing on shared meanings is particularly important when there is a need to collaborate on the design, delivery, assessment and evaluation of programs that involve unfamiliar and possibly ‘fuzzy’ terms and concepts. A range of divergent terms has been used in the interprofessional area (Table 5.1).

Table 5.1 Range of terms used to describe IPE

| PREFIXES | ADJECTIVES |

|---|---|

In recent research in Victoria, Australia, Stone and Curtis (2007) found that there was vague understanding of what IPE actually means in practice. One-hundred-and-nine comments from 57 respondents were thematically analysed, and the key IPE components of (a) teamwork, collaboration and/or interprofessional practice, and (b) community and/or patient care were identified in only 4.6% and 8.3% of comments respectively.

Use of the term ‘interprofessional’ is not confined to the domain of health. It is also used to refer to broader sets of vocational areas that are recognised as benefiting from active and systematic interaction and collaboration. School education, theology, law and the justice system, for example, are areas that are clearly important in achieving social and health improvement (Snyder 1987). Nor is it a big leap to include professions relating to the social and health impacts of natural and built environments, such as environmental science, architecture and engineering (Illinois Institute of Technology 2008). It is important to understand the interrelatedness of traditionally separate departments, disciplines and sectors, because their interdependence means that collaboration is often the only way that affordable, lasting, positive change can be effected (Graycar 2008). Our focus here is more modest, and we will limit our scope to the health and social care professions.

While the World Health Organization (1988) originally used the term ‘multiprofessional’ education (MPE), it has since adopted the more accurate term ‘interprofessional’ education (IPE) (Yan et al 2007), which has a clear emphasis on interaction between professions, rather than just the ‘presence of many’. It is important to distinguish between these terms because MPE now commonly refers to two or more professions learning side-by-side for whatever reason (Barr 2002). Sometimes the terms ‘common learning’ and ‘shared learning’ are also used to describe situations in which students from different disciplines are co-located, but may not necessarily purposefully interact.

A widely agreed international definition of IPE is: ‘Occasions when two or more professions learn with, from and about each other to improve collaboration and the quality of care’ (Freeth et al 2005, p xv).

The ‘with, from and about’ are important aspects that are often omitted from educational activities labelled ‘IPE’ but which, in fact, more closely resemble ‘MPE’. IPE can also be seen as a subset of the broader construct ‘interprofessional learning’ (IPL), which includes any sort of interprofessional experience where learning may occur, such as informal and unplanned activities at any stage before, during or after initial qualification. Barr et al (2005) offer the following definition: ‘IPL is learning arising from interaction between members (or students) of two or more professions either as a product of interprofessional education or happening spontaneously’ (p xxiii).

Why IPE and IPP?

There are also convincing arguments and some research to suggest that improvements in IPP are associated with higher levels of job morale and satisfaction among health professionals (Barr et al 2005, Day et al 2006, DeLoach 2003, Reeves et al 2008). One could logically assume that improved work morale and satisfaction should lead to better recruitment and retention. It should not be surprising that improving IPP offers a range of benefits in addition to improved patient or client care. It has been known for some time that establishing successful teamwork features, such as respectful and fair relationships, and explicitly understood roles and responsibilities, is likely to increase productivity, a sense of control, personal health and well being, and a lower risk of ‘unhealthy’ occupational stress among staff (see, for example, Ferrie 2004, Hackman & Oldham 1976, Karasek, 1979).

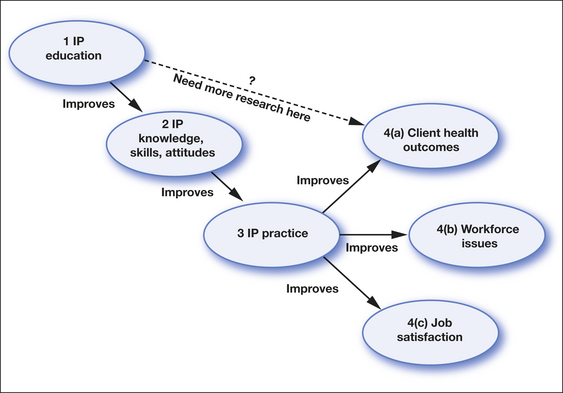

There is considerable evidence that IPE can, at least in the short term, positively affect a range of traits associated with effective IPP, such as related knowledge, skills and attitudes (Zwarenstein et al 2005). There is also a growing evidence base that effective IPP can improve health outcomes for a range of health conditions, most notably those that are chronic and complex. So while we can be confident that IPE achieves acquisition of relevant knowledge, skills and attitudes, and possibly this in turn improves IPP, the causal link between IPE and improved patient outcomes has not yet been fully demonstrated (Fig 5.1). Given the complexity of the system in which professional education occurs this link may prove extremely difficult to demonstrate, and research effort may be better expended on further exploring the role of interprofessional practice rather than IPE in improving patient outcomes.

Given the number of complex, interacting, social systems involved in IPE and IPP, it will take an extraordinary commitment of research resources, probably sustained for over a decade or more, to establish the burden of proof typically expected when working within hypothetico-deductive methodological frameworks. Such research might involve, for example, tracking large cohorts of students who (a) do and (b) do not engage in IPE during their professional preparation. They would need to be assessed at a number of stages to monitor their interprofessional development and, eventually, to evaluate the impact of this learning, first on their professional practice, and second on patient and/or community health measures. Even if such support was available for this sort of research, it would be extremely challenging to disentangle potentially confounding effects at various points in the related nomological network. Therefore, it seems unlikely that traditional bio-medical research models will be practicable in evaluating the effects of IPE and IPP, and that more eclectic, interdisciplinary and mixed-method approaches may be needed (Stone 2006b).

For the positive influence between IPE, IPP and health outcomes to be established (in Australia at least), there first needs to be significant change such that there are supportive policies and recurrent funding to instigate and support the integration and maintenance of IPE into health courses. Once this prerequisite is addressed, ensuing reform and other positive changes will require sustained support for the necessary research and evaluation to establish a substantial IPE and IPP evidence base. International experience suggests that this requires multilateral partnerships between stakeholders, such as universities, governments, service providers, and relevant consumer and professional bodies.

Box 5.1 summarises some of the main drivers for better interprofessional approaches to healthcare.

BOX 5.1 Forces for mainstreaming interprofessional approaches

What does IPE look like?

IPE occurs when two or more professions learn ‘with, from and about each other’. The context for this learning is the fostering of collaborative practice and improved quality of care. Learning activities can be evaluated in terms of relevance and suitability to IPE (Table 5.2). Low-relevance activities, such as lectures, tend to be more passive and decontextualised from applied settings, while high-relevance activities occur where students undertake learning tasks that are closer to professional life.

Table 5.2 Range of learning activities evaluated with relevance to IPE

| ACTIVITY | EVALUATION OF RELEVANCE TO IPE |

|---|---|

| Lectures | Limited scope for interprofessional interaction and its assessment; may be appropriate for delivery of knowledge-based components and content about other professional roles, the need for and principles of interprofessional practice, teamwork, collaboration, supporting research, models, issues, international developments. Traditionally passive, but interactive–experiential large-group teaching methods are emerging that better support IPE. |

| Practical/applied or lab-based learning | High experiential value (usually has a technical skills-acquisition focus) but may have limited opportunities for interaction between students. Can be structured to incorporate different disciplines working together to acquire or practise a specific skill. |

| Tutorial | Can range from low to high experiential components. Scope for student interaction, and its assessment varies in proportion to how active or passive the teaching strategies are: pure listening, reading and writing vs discussion, self-directed, inquiry, problem or case-based learning, simulation or role-play. Tutorial-based learning can be highly effective as a way of exploring interprofessional approaches. |

| Online learning | May involve individual learning and group activities with varying levels of interaction depending on design of the unit. Interaction is limited to a ‘virtual’ environment and may be experienced by students as too divorced from the ‘real world’ to provide a highly effective interprofessional learning experience. |

| Simulation | Some simulation environments (e.g. emergency care) are ‘high fidelity’ in their ability to simulate actual clinical environments and provide realistic opportunities for team-based patient care. Simulation can be structured to incorporate different disciplines working together to acquire or practise a specific skill (e.g. physiotherapy, medical and nursing students learning together in a simulated setting to manage aspects of cardiorespiratory patient care). |

| e-clinics | Opportunities to observe recorded or real-time patient—professional interactions and team interactions. When combined with collaborative, experiential small-group or tutorial opportunities provides learning opportunities for IPE. |

| Fieldwork | Ranges from work shadowing (observational) to practice under supervision. Opportunities for IPL may be structured or incidental. There is significant potential for structured IPE opportunities where students share patients, complete joint assessments, engage in collaborative group problem solving and interactive discussion of the process of teamwork and IP clinical care. |

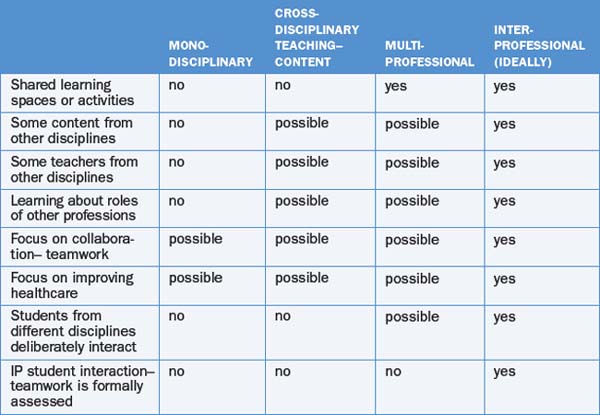

The matrix shown in Table 5.3 has proven useful in planning programs and learning activities as students progress through their courses, for example, by incrementally increasing relevance of experiences as they develop more professional levels of associated competence. It also offers a clarification of terms, especially the difference between ‘multi’ and interprofessional education.

In the shorter term, it seems unlikely that all of the ‘ideal’ IPE conditions in the right-hand column (Table 5.3) can be addressed at once in most settings. However, using this schema as a guide may assist with forward planning based on the principle that the more of these features that can be provided, the greater the likelihood of durable and transferable learning taking place.

As can be seen from the examples in Tables 5.2 and 5.3, there are many possible IPE pathways that can evolve from the complex systems typically involved in preparation for practice and continuing professional development within the health workforce. Rather than replacing or imposing further layers upon existing programs, IPE requires adjusting how these programs unfold, while still addressing important extant discipline-specific learning outcomes. While some elements of existing ‘model’ programs may be borrowed, or more likely adapted, it would be very difficult to transplant a program intact from one setting to another. Some have been inspired by exemplary practice, such as the Southampton New Generation Project (O’Halloran et al 2006), and sought to use it as a blueprint. However, the learning and practice context and the relationships are important success factors in IPE. Therefore direct application of an existing program risks early failure if it is not adapted to fit well with local practice and does not involve the local stakeholders in the development process. The ACT Interprofessional Learning Project is an example of a health department-led initiative (Box 5.2) and the Southampton New Generation Project (Box 5.3) is an example of a university-led IPE program. It should be noted that both projects required substantial financial and human resources in their development and implementation phases.

BOX 5.2 The ACT Interprofessional Learning Project

The Australian Capital Territory encompasses the environs of the national capital, Canberra. The ACT IPL project aims to establish and grow an interprofessional culture in healthcare in the ACT. The project commenced with a comprehensive review of the literature (Braithwaite & Travaglia 2005) and a series of discussion papers and, subsequently, an IPL framework and implementation plan. The plan encompasses the health authority (ACT Health), healthcare facilities, education institutions, professional bodies, healthcare teams, managers and professionals. IPL at a pre- and post-qualification stage, at an individual and organisational level, is the target of the project.

Online. Available: http://health.act.gov.au/c/health?a=sp&did=10153142 accessed 18 Dec 2008

BOX 5.3 The Southampton New Generation Project

In 2005 the Universities of Southampton and Portsmouth embarked on a project that now incorporates a number of short IPE experiences into the curricula of fourteen disciplines. Students undertake three units of interprofessional learning across their program (O’Halloran et al 2006). The first unit introduces students to team roles and teamwork. The second unit involves a clinical audit task and further development of collaborative teamwork skills. In the third unit student teams undertake a service improvement project requiring them to engage in interprofessional problem solving. Unit 1 is based at the university campus while Units 2 and 3 are fieldwork based.

Online. Available: http://www.commonlearning.net/ Accessed 18 Dec 2008

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree