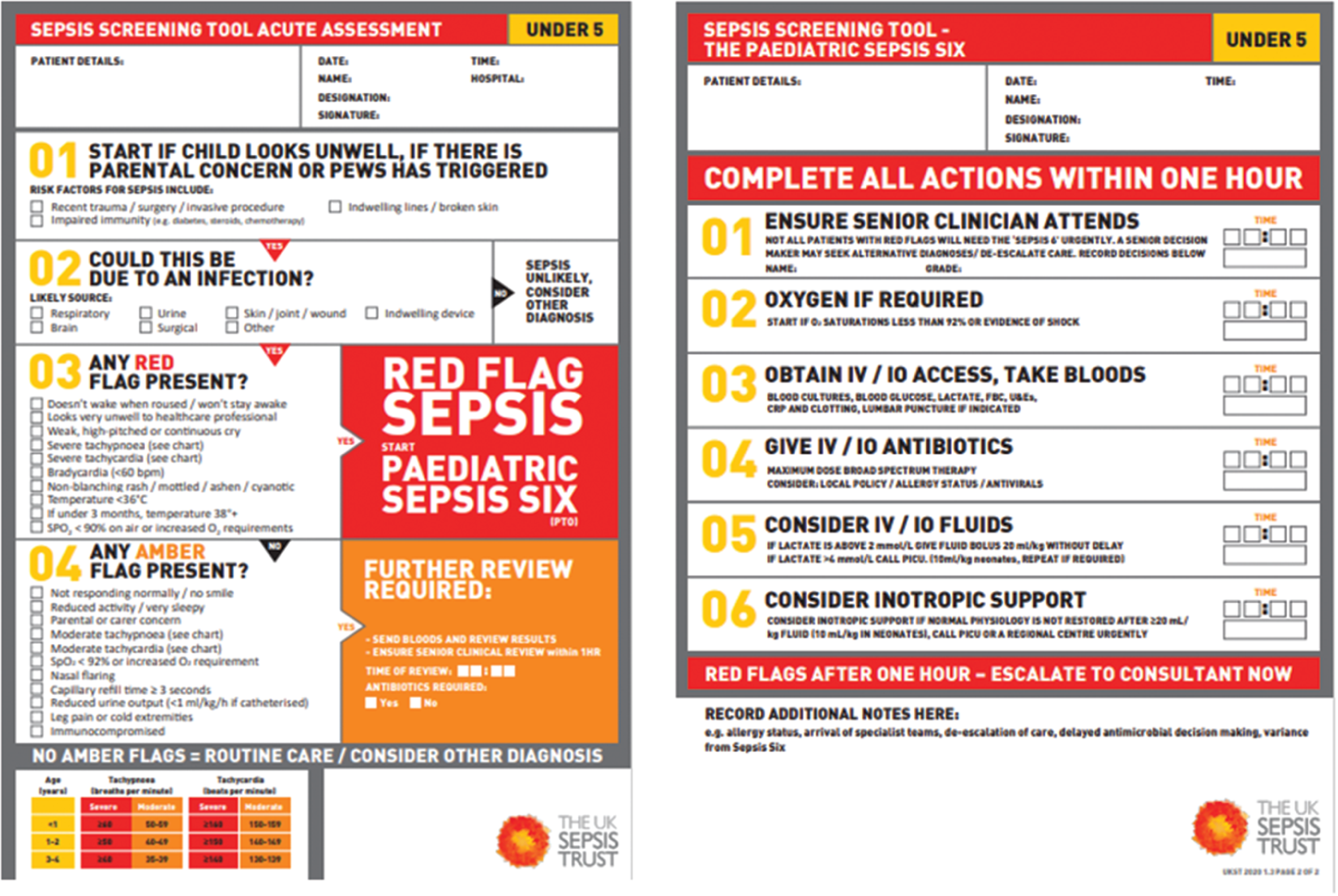

Carolyn Green and Doris Corkin Caring for a critically ill child can be very complex and challenging. Critical illness can be defined as a clinical state which may result in respiratory, cardiac, neurological, gastrointestinal, metabolic, renal, and haematological complications (Nadel & Kroll 2007). Managing the care of a critically ill child requires rapid and systematic clinical assessment to detect physiological instability so that timely, prompt, and effective resuscitation and stabilisation may occur before the onset of organ failure. The cornerstones of paediatric intensive care management are the optimisation of a patient’s physiology, the provision of advanced organ support, and the identification and treatment of underlying pathological processes. This is best achieved through a multidisciplinary team approach, with shared responsibility and decision making (Jackson & Cairns 2021). This chapter will outline the approach required by the interprofessional team when involved in the assessment and subsequent care planning for a child with a critical illness. The case study relating to a child with meningococcal sepsis will illustrate each stage of the process within an ABCDE framework (Resuscitation Council UK 2021). Martha, a two-year-old girl, has been admitted to hospital following emergency referral by her GP with a history of being unwell for the past 24 hours with high temperature, vomiting, and refusing to feed. The GP reported that she had an increased heart rate and respiratory rate, some non-blanching petechiae, and felt that she might be presenting with symptoms of meningococcal disease and/or sepsis. The GP administered parenteral benzyl penicillin and secured intravenous access before Martha was transported to hospital by ambulance. Martha was accompanied by her mother who was extremely anxious about her daughter’s condition. She was concerned that her child’s hands and feet were very cold and remarked on her pale, mottled skin. Although Martha was constantly crying she was, according to her mother, becoming drowsy. The history given by Martha’s mother and the GP’s initial diagnosis of meningococcal disease and/or sepsis and subsequent administration of parenteral benzyl penicillin suggests that this child’s condition is critical. Note two major clinical forms of meningococcal disease are meningitis and septicaemia but most will have a mixed presentation. Meningitis can be bacterial or viral with the bacterial causes of infection including Neisseria meningitidis, Meningococcus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, and Haemophilus influenzae type B (Alamarat & Hasbun 2020). Meningococcal disease is not only associated with increased risk of mortality but also long-term morbidity. Despite the successful introduction of the serogroup meningococcal vaccines since 1999, meningococcal disease still remains one of the leading causes of death from infection in early childhood globally (Wright et al. 2021). The disease has an early non-specific stage, with signs such as fever, lethargy, irritability, nausea, and poor feeding. Cold extremities and abnormal skin colour are associated with developing invasive meningococcal disease (Thompson et al. 2006), which progresses rapidly to clinical meningitis and/or septicaemia. Clinical meningitis is characterised by fever, lethargy, vomiting, headache, photophobia, neck stiffness, and positive Kernig’s sign and Brudzinski’s sign. Petechiae or purpura may also be present. Meningococcal septicaemia is characterised by fever, petechiae, purpura, and shock. Sepsis is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in children worldwide and is defined as life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection (Singer et al. 2016). Sepsis with shock is a life-threatening condition, and in 2020 the Surviving Sepsis Campaign proposed a definition for septic shock in children: ‘severe infection leading to cardiovascular dysfunction (including hypotension, need for treatment with a vasoactive medication, or impaired perfusion)’. Early identification and appropriate resuscitation and management are therefore critical to optimising outcomes for children with sepsis (Surviving Sepsis Campaign 2020). Over the past decade there has been a significant improvement in survival from sepsis in the developed world. This has been attributed to the fact that the basic principles of sepsis have become widely accepted, in part by global initiatives such as the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (2020) and the formulation of national guidelines such as NICE NG51 (2016). The main principles of progressive sepsis care are: (Jackson & Cairns 2021) Martha’s symptoms would suggest that she has progressed from the non-specific early stage of meningococcal disease and is rapidly developing disease patterns associated with meningococcal septicaemia. Achieving the best possible outcomes for Martha as previously stated requires rapid and systematic clinical assessment to detect physiological instability so that timely, prompt, and aggressive resuscitation and stabilisation will occur before the onset of organ failure. However, improving health outcomes for this child lies outside the scope of any single practitioner (Headrick et al. 1998). This assumption remains very evident in emergency care situations when the number of professionals involved and the importance of their ability to work collaboratively increases with the complexity of the child’s condition. The delivery of high-quality care with optimal patient safety in these situations is dependent on effective interprofessional team management. This highlights the need for developing interprofessional working models (DH 2005), whereby expertise in assessment, planning, and treatment interventions are timely and promote stabilisation of the critically ill child. Interprofessional team-based models of care bring a range of professionals together to share different knowledge and experiences and aim to bridge gaps and negotiate overlaps in roles and minimise risk (Schot et al. 2020). A powerful incentive for greater teamwork among professionals is created when there is respect and understanding of the role of each of the team members and recognition of the unique contribution of each individual in a critical care situation. In a well-practised team, each member knows in advance their role and regards the leader as the person who co-ordinates, directs the assessment, and consults with other members regarding problem identification and subsequent care or management planning. Therefore interprofessional working models require that the level of equality of esteem and power in formal decision-making is balanced within the professional roles of doctor and nurse (Stocker et al. 2016). Indeed effective multidisciplinary team working is at the heart of providing high quality and safe care (DHSSPS 2007). The role of education in encouraging interprofessional working is crucial in promoting collaboration, team working, and establishing roles and responsibilities (WHO 2010), particularly in a critical care situation. Education and competency-based training of interprofessional teams should include recognition of the acutely ill child, clinical assessment, appropriate interventions, and recognition of deterioration whereby senior assistance becomes necessary. Simulation as an educational strategy involves not only technological and computerised facilities, but includes important human interactions. High fidelity simulation using Simbaby provides opportunities for users at all levels, from novice to expert, to practice and develop skills with the knowledge that mistakes carry no penalties or fear of harm to patients or learners (Bradley 2006; Corkin & Morrow 2011). Using simulations within an interprofessional educational programme seeks to provide participants with a meaningful learning experience and has become increasingly recognised as having great potential in delivering elements of healthcare education (Bradley 2006; McNaughten et al. 2020). It integrates the cognitive, psychomotor, and affective domains in a non-threatening and safe environment (Underberg 2003). Irrespective of a healthcare practitioner’s chosen speciality, cognitive and psychomotor skills pertinent to assessing a patient’s respiratory function, cardiovascular status, and level of pain must be acquired (Rogers et al. 2001). Human patient simulators enable the replication of rarely witnessed critical events, ensuring all healthcare practitioners are exposed to the same standard of training. In addition, complex skills such as communication, critical thinking and decision-making, and team working thus receive attention. Interprofessional development of protocols for the assessment and management of the sick child include physiological warning systems, whereby clinical parameters outside the normal ranges (see Table 8.1) indicating deterioration are subsequently detected and medical interventions can be implemented at an early stage. Table 8.1 Normal ranges (Meningitis Research Foundation 2010). The Glasgow Meningococcal Septicaemia Prognostic Scoring Tool is a scoring system which may determine the severity of the child’s illness and subsequent deterioration (see Table 8.2). Table 8.2 Glasgow meningococcal septicaemia prognostic scoring tool (Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network 2008). Add scores to give result Score > or = to 8, or an escalating score is indicative of serious and rapidly progressing disease. Note the UK Sepsis 6 Trust Screening Tool (Nutbeam & Daniels 2022) can be used to support the implementation of the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidelines (2019), for management of sepsis and identification of early warning signs (see Table 8.3). Agreed assessment methods must consider the unpredictability of the timeframe, the multiple parameters that require observation and the swift spiral effect of deterioration in the sick child (Teasdale 2009). Prioritisation and effective action requires identification of one’s own limitations and promptly identifying the most appropriate person within the multidisciplinary team to carry out an appropriate assessment and ensure that immediate action is taken (DHSSPS 2007). This requires the utilisation of an effective communication tool such as SBAR. This is a situational briefing model which uses a clear structure ensuring the provision of all relevant information organized in a logical fashion (Lee et al. 2016). It helps ensure that important information is transmitted in a predictable structure, when summoning senior nursing and medical staff when support for the management of a child’s deteriorating condition is vital. The SBAR tool is regarded as a communication technique that increases patient safety and is current ‘best practice’ to deliver information in critical situations (Muller et al. 2018). SBAR stands for the following (Leonard et al. 2004); The hospital ward or emergency department will have been informed of Martha’s anticipated arrival and this provides an opportunity for the nursing and medical team to prepare for immediate assessment and management of her clinical state in a systematic and organised way. Do refer to activity 8.1 and 8.2. The hospital environment where the child is admitted to will have: Fluid volumes, drug dosages, and correct equipment size will depend on the weight of the child. Martha’s mother may know what her weight is; if not then it may be worked out quickly to avoid delay in treatment interventions. A formula for estimating weight in kilograms is: Weight (kg)=(age+4)×2

CHAPTER 8

Interprofessional Assessment and Care Planning in Critical Care

INTRODUCTION

CASE STUDY

INTERPROFESSIONAL WORKING

Age

Respiratory rate

Heart rate

Systolic BP

< 1

30–40

110–160

70–90

1–2

25–35

110–150

80–95

2–5

25–30

95–140

80–100

5–12

20–25

80–120

90–110

> 12

15–20

60–100

100–120

Clinical signs

Points

BP < 75 mmHg systolic, age < 4 y < 85 mmHg systolic, age > 4 y

3

Skin/rectal temperature difference > 3°C

3

Modified coma scale score < 8 or Deterioration of > or =3 points in 1 hour

3

Deterioration in hour before scoring

2

Absence of meningism

2

Extending purpuric rash or widespread ecchymoses

1

Base deficit (capillary or arterial) >8.0

1

Maximum score

15

IMMEDIATE ASSESSMENT OF THE CRITICALLY ILL CHILD

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree