Interpersonal Skills and Human Behavior

Learning Objectives

1. Define, spell, and pronounce the terms listed in the vocabulary.

2. Explain why first impressions are crucial.

3. Differentiate between verbal and nonverbal communication.

4. Identify styles and types of verbal communication.

5. Explain the different levels of spatial separation.

6. Analyze the effect of hereditary, cultural, and environmental influences on communication.

7. Discuss the value of touch in the communication process.

8. Recognize the elements of oral communication using a sender-receiver process.

9. Explain the value of active listening.

10. Define and understand abnormal behavior patterns.

11. Recognize commonly used defense mechanisms.

12. Discuss the role of assertiveness in effective professional communication.

13. Identify the roles of self-boundaries in the healthcare environment.

14. List several ways to deal with conflict.

15. Recognize communication barriers.

16. Identify techniques for overcoming communication barriers.

17. Differentiate between adaptive and nonadaptive coping mechanisms.

19. Discuss using empathy when treating terminally ill patients.

20. Identify resources and adaptations that are required based on individual needs.

21. List and explain the levels of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

22. Discuss why physical and emotional needs affect our daily performance at work.

Vocabulary

adage (a′-dij) A saying, often in metaphoric form, that embodies a common observation.

ambiguous (am-bi′-gu-wus) Capable of being understood in two or more possible senses or ways; unclear.

animate To fill with life; to give spirit and support to expressions.

battery An offensive touching or use of force on a person without his or her consent.

caustic (kos′-tik) Marked by sarcasm.

channels Means of communication or expression; courses or directions of thought.

comfort zone A place in the mind where an individual feels safe and confident.

decodes Converts, as in a message, into intelligible form; recognizes and interprets.

defense mechanisms Psychological methods of dealing with stressful situations that are encountered in day-to-day living.

encodes Converts from one system of communication to another; converts a message into code.

encroachments Actions that advance beyond the usual or proper limits.

enunciate (e-nun′-se-at) To utter articulate sounds; the act of being very distinct in speech.

external noise Sounds or factors outside the brain that interfere with the communication process.

externalization The attribution of an event or occurrence to causes outside the self.

internal noise Factors inside the brain that interfere with the communication process.

language barrier Any type of interference that inhibits the communication process and is related to languages spoken by the people attempting to communicate.

litigious (luh-ti′-jus) Prone to engage in lawsuits.

malediction (ma-luh-dik′-shun) Speaking evil or the calling of a curse.

paraphrasing To express an idea in different wording in an effort to enhance communication and clarify meaning.

perception Capacity for comprehension; an awareness of the elements of the environment.

physiologic noise Internal interferences comprised of biological factors within a speaker or listener that hinder effective and accurate communication.

pitch Highness or lowness of a sound; the relative level, intensity, or extent of some quality or state.

sarcasm A sharp and often satirical response or ironic utterance designed to cut or inflict pain.

stressors Stimuli that cause stress.

thanatology (tha-nuh-tah′-luh-je) The study of the phenomena of death and of psychological methods of coping with death.

vehemently (ve′-uh-ment-le) In a manner marked by forceful energy; intensely, emotionally.

volatile (vah′-luh-til) Easily aroused; tending to erupt in violence.

Scenario

Many types of patients seek medical attention and care in the physician’s office. Each has different needs and different concerns, even if the diagnoses are similar. Communication and interpersonal skills are vital in meeting these needs and providing optimum care to the patient. However, the patient is not the only individual to consider. Family members often are crucial to the health and well-being of the patient.

Lucille Cloyd is an 83-year-old patient who has been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and is seeing Dr. Neill for treatment. Her daughter, Sarah Smithson, helps to care for her; she is close to her mother emotionally. Sarah also is Dr. Neill’s patient. Although Sarah does not want to see her mother in pain, she suffers with the knowledge that life will be very different without her. Mrs. Cloyd is widowed and visits the physician once a month in addition to receiving hospice services. She is a good-humored woman who feels that she has led a fruitful life, yet she has moments of depression. She has been living with Sarah and her family for 2 months and enjoys interacting with her two grandchildren and the family’s pets.

The medical assistant must consider not only Mrs. Cloyd, but also her extended family. Compassion and sensitivity are necessary to care for this patient, in addition to excellent listening skills. A good knowledge of human relations helps the medical assistant make Mrs. Cloyd’s medical care as pleasant as possible under the circumstances.

While studying this chapter, think about the following questions:

• How can the medical assistant treat patients as individuals during a busy workday?

• How does the medical assistant effectively communicate with a patient’s family members?

• How will developing good listening skills make the medical assistant more effective?

• How do friends and family members play a role in the health of the patient?

The interpersonal skills developed by the medical assistant help to set the tone of a medical office. Interpersonal skills include the communications process and how we relate to one another during that process. Human relations can be defined as the study of the problems that arise from organizational and interpersonal contact. The two entities intersect, and the successful medical assistant continually works to enhance these attributes. Patients who visit the healthcare facility may not be at their best, and the way in which the medical assistant reacts to and interacts with them can make an incredible difference in their perception of the office, the physician, and the medical staff. These interactions may also affect the patient’s treatment and recovery.

First Impressions

Our elders have stressed all our lives that first impressions are lasting ones, and this old adage is still true! The opinions formed in the early moments of meeting someone remain in our thoughts long after the first words have been spoken. The first impression involves much more than just physical appearance or dress; it includes attitude and compassion, and the all-important smile (Figure 5-1).

One of the primary objectives of the professional medical assistant is to care for and about the people being served. Patients are the reason the facility exists, and they should be offered the best customer service possible. They must be welcomed warmly, and it is important to call patients by their names. People enjoy hearing their names, and it gives a patient confidence that the medical staff members know for whom they are caring.

Think for a moment about how it feels to be a new patient entering the unknown territory of the physician’s office. Staff members of the facility are in familiar surroundings and already have some information about the new patient. However, the patient knows nothing about the staff members. One way to break that barrier is to have all staff members wear name badges, with letters large enough to be read at a distance of 3 feet. Include the staff position if several divisions of responsibility exist (e.g., “medical assistant,” “insurance biller,” and “office manager”). When the patient approaches, if you are wearing a name badge, make introductions and smile. Smiles should show in the voice and the eyes. Genuinely welcome the patient to the office. This small effort helps put the patient at ease in the office environment.

Some physicians make brief notes in the medical record about the personal life of the patient. When the patient arrives for an appointment, the physician can ask about a recent trip abroad or a new grandchild. This tells the patient that the doctor and the office staff see him or her as more than just an illness or a medical record number. It gives the impression that they truly care, and that impression should be an accurate one. Once an impression is formed in the patient’s mind, it is very difficult to change; therefore, make the first impressions of your office positive ones. The events in a patient’s life can drastically influence the person’s health, and any information that would be beneficial to the physician in treating the patient belongs in the medical record.

Patient-Centered Care

Healthcare professionals have embraced patient-centered care, an innovative approach to plan, deliver, and evaluate healthcare that is grounded in mutually beneficial partnerships among healthcare providers, patients, and families. Patient- and family-centered care applies to patients of all ages and may be practiced in any healthcare setting. Each patient that seeks care from the physician has a unique set of needs, including clinical symptoms that require medical attention and issues specific to the individual that can affect his or her care. As patients navigate the healthcare delivery system, physicians and their employees must be prepared to identify and address not just the clinical aspects of care, but also the spectrum of each patient’s demographic and personal characteristics. Good communication skills are vital to meeting the needs of the patient and his or her support system.

Communication Paths

Verbal Communication

Peter Urs Bender suggests several types of verbal communication in his book “Guide to Strengths and Weaknesses of Personality Types,” including:

1. Expressive – talkative, excited, enthusiastic.

2. Decisive – domineering, controlling, authoritarian.

3. Amiable – nurturing, positive, helpful.

The medical assistant can develop enough perception to determine the type of verbal communication that a patient uses most often. Then, by studying these four types, it will be easier to communicate verbally with each of the personality types. Think about family members and close friends – what personality type might they be?

The pitch of the voice is a part of verbal communication. The voice lifts at the end of a question. It drops at the end of a statement. Usually when a speaker intends to continue a statement, the voice holds the same pitch, the head remains straight, and the eyes and hands are unchanged. This is not an appropriate time to interrupt. If the message is interrupted, the train of thought may not be completed. The tone of voice and choice of words also affect messages.

The medical assistant should speak clearly and enunciate words properly. Speak loudly enough that the patients are able to hear clearly, and pay particular attention to those who wear some type of hearing assistance device. It is wise to note this information on the patient’s medical record to jog the memory when a patient with a hearing problem visits the office. Never assume that just because a patient is elderly, he or she has a hearing problem. When talking with patients, be sure to use the volume of speech to an advantage. Always speak at a clearly audible level, but at times it will be necessary to increase or decrease the volume of speech. When a patient is upset, for instance, it often helps to lower the volume of speech, because the patient tends to get quieter to hear the person speaking.

Eye contact is critical, especially in the age of electronic medical records. Look at the person to whom you are speaking and do not forget a genuine smile. Look at the person more than at the computer. Many people feel that a person who speaks and cannot look another in the eyes is being deceptive. It also can mean that the speaker is very shy and has little self-confidence. Use gestures where appropriate to liven speech and animate the conversation.

Medical assistants must become aware of how they express themselves and how they affect the feelings of others. The tone of voice is vital. Sarcasm and caustic remarks have no place in the medical office. For example, telling a patient, “I hope you can manage to be on time for your next appointment” is needless and rude. The medical assistant must be conservative when speaking and must not be too familiar. The patient expects professionalism and has the right to demand this in the healthcare setting. Never make an inappropriate remark and follow with “I was just kidding.” This is never used in a medical facility or in any type of interpersonal communication. Take special care not to hurt anyone’s feelings with words and phrases. Be very careful about what is said, especially to patients (Procedure 5-1).

Remember that patients are in the facility to be treated by the physician and staff. They usually are concerned about their illness and may have great apprehension and fear about the future. It is completely out of place for the medical assistant to talk about his or her personal life and challenges with the patients. Allow the patient to speak, and listen instead of offering personal information. Often patients casually mention details to the medical assistant that might influence their care. The saying that we are given “one mouth and two ears” stresses which should get more use!

Nonverbal Communication

Both verbal and nonverbal communications are important in the art of expression, and both are needed to succeed in the communication exchange. Nonverbal communication involves messages conveyed without the use of words. They are transmitted by body language, gestures, and mannerisms that may or may not be in agreement with the words the person speaks. Body language is partly instinctive, partly taught, and partly imitative. It involves eye contact, facial expression, hand gestures, grooming, dress, space, tone of voice, posture, touch, and much more. We are often unaware of our own nonverbal signals and consciously recognize only a small number of the signals sent by others. Our ability to help others increases as we hone our own skills in interpreting nonverbal communication; it is almost always more accurate than verbal communication and tends to convey our true feelings and beliefs (Procedure 5-2).

Appearance is an integral part of nonverbal communication. Our appearance influences the way others view us and can present a conflicting message, or even a totally incorrect message. When we see someone who dresses or grooms in a way that is very different from our own style, we tend to assume that the personalities are also very different. This is not always true. Although we should not judge people by the way they dress, it is difficult not to form opinions based on what we see. Visible piercings and tattoos often are regarded unfavorably in the medical profession, as are long, brightly painted nails. Although these do not signify that the wearer is not professional, many patients, especially older patients, are uncomfortable with these trends. For this reason alone, the medical assistant who is less conservative may diminish his or her chances for certain jobs and advancements. Expressing oneself is healthy, yet in the medical profession, a conservative appearance is mandatory so as not to raise obstacles to communication.

The successful medical assistant expresses self-esteem and confidence by stance, vocabulary, facial expression, and a caring attitude. The experience of speaking to someone who does not make eye contact helps one realize the importance of greeting the patient with the eyes as well as the voice and body language. Facial expressions often convey our true feelings and are not masked by the words we use. Our eyes often tell the truth when our words are misleading or false. Use an open body stance when dealing with patients. Crossed arms and legs hint that you are “closed” to the person to whom you are speaking, and this may be construed as disinterest or disbelief. Nonverbal and verbal communication are interdependent (Figure 5-2); they must be in harmony to convey an accurate message that the receiver can easily interpret. If the two are not congruent, the nonverbal presentation usually is dominant and expresses the true message.

The need for boundaries, or personal space, is demonstrated by how patients in the reception area choose a seat. Proxemics is the study of the nature, degree, and effect of the spatial separation individuals naturally maintain and how this separation relates to heredity, cultural, and environmental factors. Seldom does a person sit in a space next to a stranger if another option is available. Although the need for space varies with the individual culture, some might even remain standing to satisfy the need for personal space. Public space usually is accepted as a distance of 12 to 25 feet, and social space usually is considered to be 4 to 12 feet. Personal space ranges from 1½ to 4 feet, and intimate contact includes physical touching to approximately 1½ feet. The medical assistant often can tell when he or she has invaded someone’s personal space, because the person tends to back up a step or two. If this happens, take a small step back and respect the boundaries being set. The more familiar and comfortable patients are with the medical assistant, the closer the space they allow. Other types of boundaries are discussed later in the chapter.

Touch is a powerful communicator. The soft acceptance of shaking someone’s hand, to the good-natured pat on the back, to the harsh slap on the face all relay different messages that need no words to express accurately. In the medical profession, as in any business, touch can be comforting or can lead to a sexual harassment suit. Individuals who have experienced sexual abuse or other traumatic experiences may not want to be touched at all. Unfortunately, one must be extremely careful when using this effective communication tool. In today’s litigious society, any nonconsensual touching may be considered battery, and touch should be used with great discretion and caution.

The medical assistant should not be afraid to touch patients appropriately, such as giving a pat on the back or a squeeze of the hand (Figure 5-3). Some patients are receptive to a brief sideways hug, whereas others would take this as an intrusion into their personal space. Certainly patients with serious illnesses appreciate touch as an expression of empathy. Never be afraid to touch sick patients, especially those with diseases such as acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), as long as proper precautions are followed where indicated. If unsure, ask a patient whether he or she minds being hugged. These patients need to feel acceptance, and the attitude of the medical staff members they encounter directly influences their adherence to keeping their appointments with the physician. If they do not feel accepted and cared for, they will not return to the physician’s office. A gentle touch and a smile do wonders for showing care and concern.

Posture can signal depression, excitement, anger, or even an appeal for help. When the physician sits at the front of the chair and leans forward, he or she is sending a message of care and interest. Positioning also is important. Sitting behind a desk promotes an air of authority. Standing or sitting across a room may convey a negative message of denying involvement or reluctance to talk. Sitting side by side with a patient helps initiate trust and promote open conversation. The medical assistant should practice good postural techniques as a part of projecting a positive image and for personal health reasons.

The Process of Communication

Anyone who works in the realm of public service should develop good communication skills. It is important to be able to interact with others and to put them at ease so that their comfort level increases and they develop trust. To communicate well, we first must have a general understanding of the process of communication. Once a message has been sent, it cannot be retrieved and restated or expressed in a different way. Especially in the medical profession, communication must be clear and concise, and the message we intend to send must match what the receiver understands.

Although many different scientific models of communication exist, the one that best fits most types of communication is the transactional communication model. Before students can understand how this model works, they must understand the elements we use to communicate.

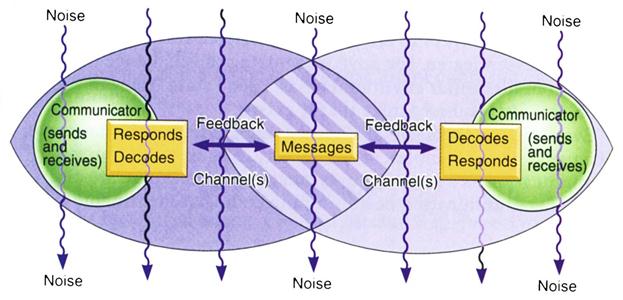

When two people interact, both people usually act as senders and as receivers (or communicators). The sender is the person who sends a message through a variety of different channels. Channels can be spoken words, written messages, and body language. The sender encodes the message, which simply means that he or she chooses a specific means of expression using words and other channels. The receiver decodes the message according to his or her understanding of what is being communicated. However, sometimes the receiver misunderstands the message. This often is a result of noise, which is anything that interferes with the message being sent. It can be literal noise, such as a radio or a jackhammer on the street outside; this is called external noise. Or it can be internal noise, which includes the receiver’s own thoughts or prejudices and opinions. Physiologic noise also interferes with communication. This includes any biologic factor that would prevent the communicator from sending or receiving accurate messages, such as not feeling well or being overly tired. Feedback can be given through verbal expressions or body language, such as a simple nod of understanding. The perception of the receiver is very important and is discussed later in this chapter.

The transactional communication model (Figure 5-4) depicts “communicators” instead of one sender and one receiver. If two people are communicating, both are sending and receiving messages and both are encoding and decoding messages. Even when two people are speaking one at a time, messages are continually sent with words, body language, facial expressions, and gestures. Various channels of communication are used, and both communicators offer feedback, including subconscious feedback. Noise may or may not be present, but even the best communicators experience some type of noise, even if that is only thinking of what to say next.

Listening

Listening is just as important to good communication as the spoken word. Hearing is the process, function, or power of perceiving sound, whereas listening is defined as paying attention to sound or hearing something with thoughtful attention. Patients need to know that the medical assistant is listening. This is actually true in all interpersonal relationships, including husband-wife, parent-child, supervisor-employee, and doctor-patient interactions. When listening to someone who is attempting to communicate, the first rule is to look at the speaker and pay attention. Sometimes it is important not to respond immediately but to remain silent and offer an understanding and reassuring nod.

Sometimes it is hard to listen. We may not be able to listen effectively, because we are distracted by our own thoughts. Perhaps the situations occurring in our own lives make the conversation we are hearing seem meaningless and unimportant. Or so many messages may be attacking at once that we are unable to focus on any specific one to listen to what is being communicated. At other times, such as in anger, we are so rapidly preparing our response that we cannot listen to what is being said. We may simply be too tired to listen, or we may have prejudged the speaker and decided that we do not need to listen. However, while working with patients, the medical assistant must be diligent not only in hearing the words being spoken, but also in listening to them and to what the patient is attempting to communicate.

Active listening is a skill that enables a person to paraphrase and clarify what the speaker has said. Paraphrasing is listening to what the sender is communicating, analyzing the words, and restating them to confirm that the receiver has understood the message as the sender intended. This process clarifies the speaker’s thoughts and helps indicate that a common understanding of the message exists between the speaker and the receiver. When communicating in this way, the receiver should reword what the sender has said and then ask a clarifying question. Consider the following example:

| Patient: | “I haven’t been feeling well lately.” |

| Medical assistant: | “You say you have not been feeling well. What exactly is the trouble?” |

This type of communication may seem awkward at first, because most of us believe that listening involves lack of speech. Active listening means that the speaker’s words are heard, and a restatement is used to verify that the message was understood correctly. This statement gives the speaker the opportunity to correct any misconceptions or misunderstandings. Consider the following example:

| Patient: | “My back hurts.” |

| Medical assistant: | “Where does it hurt?” |

| Patient: | “In the middle.” |

| Medical assistant: | “Can you point to exactly where it hurts?” |

| Patient: | “Yes, right here (points).” |

| Medical assistant: | “Is it a sharp or dull pain?” |

| Patient: | “Very sharp.” |

| Medical assistant: | “How often does it occur?” |

| Patient: | “Several times a day.” |

| Medical assistant: | “Can you tell me on an average day how many times it bothers you?” |

| Patient: | “About six times.” |

| Medical assistant: | “How long does it last?” |

| Patient: | “About 10 or 15 minutes.” |

| Medical assistant: | “How long have you felt this pain?” |

| Patient: | “For about 2 weeks.” |

| Medical assistant: | “So you have had a sharp pain in this part of your back about six times a day lasting for up to 15 minutes for 2 weeks? Is that correct?” |

| Patient: | “Yes.” |

It would have been easier if the patient had said, “I have had a sharp pain in my back that lasts up to 15 minutes, and it happens about six times a day.” This example shows how the medical assistant can continue clarifying until the answer is specific enough, which is critical when obtaining information from the patient.

It also is best to ask “open” rather than “closed” questions. An open question requires more than a “yes” or “no” answer. It forces the patient to provide more detail and expand on his or her thoughts. A closed question can be answered with “yes” or “no” and compels the medical assistant to spend more time obtaining the answers needed to document the patient’s needs thoroughly.

Often when a person or patient is talking with the medical assistant, the person is looking for a specific type of response. Some patients want advice, some want sympathy, and others are looking for reassurance. Many patients open up more quickly and more completely to the medical assistant than to the physician. This can be a very positive aspect of the relationship the medical assistant has with patients, because it is important to build good rapport with them. However, the medical assistant should never agree to withhold information from the physician under any circumstances. If the patient asks that the assistant not reveal something to the physician, the medical assistant should politely explain that he or she has an ethical obligation to report any and all pertinent information to the physician, especially if it affects medical care. For example, if the patient asks the medical assistant not to tell the physician that the patient has been smoking against medical advice, the assistant could be jeopardizing the patient’s care if the information is not reported.

This does not mean that specific details must always be aired. If the patient reveals that her stress levels have been high because she has filed a sexual harassment suit against her boss, but she does not want to share each detail with the physician, the medical assistant could report to the physician that the patient is having some legal problems that have resulted in additional stress at work. The physician will understand that the patient’s stress level is elevated and can effectively treat the patient without knowing the specific, intimate details of the acts between the patient and her employer. However, the medical assistant must never agree to lie to the physician. The patient must understand that if the physician questions any information given by the patient, it must be revealed so that the physician is assured that the care provided is appropriate. Remember that the physician may have worked with the patient for a long time and has a better understanding of the patient’s needs than the medical assistant. One patient may be able to handle a high stress level, and another may crumble at the first sign of stress. Good physicians know their patients and keep accurate, complete records that aid decision making in these situations.

If the medical assistant is ever in doubt about telling the physician something a patient has said, the best solution is to tell. Medical professionals are legally bound to confidentiality, and the patient may need to be reminded of this. Encourage the patient to talk to the physician and communicate all concerns, no matter how insignificant they may seem. Never display a judgmental attitude or express negativity about the patient’s activities, thoughts, or behavior. Offer to be with the patient, if he or she desires, during difficult discussions with the physician or to make arrangements for a special counseling session with the physician if this is indicated. Some patients are hesitant to initiate a conversation with the physician because they feel they are taking too much time. The medical assistant can help ensure that critical issues receive the doctor’s attention.

Warnings Against Advising a Patient

The medical assistant must be extremely careful when making suggestions or comments to a patient to prevent legal accusations of practicing medicine without a license. Often a patient asks for an opinion as to which course of action to take. Medical assistants are not qualified to give any type of advice to a patient. Strict laws in most states prohibit anyone other than a licensed physician from offering medical advice. Even if the patient asks what the medical assistant would do if presented with the same options, the assistant cannot encourage the patient to choose one option over another. The assistant can offer a listening ear, though, and help the patient process his or her own thoughts. This can be done in much the same way as using active listening techniques. When a patient expresses a concern, the medical assistant should restate the concern and then ask a clarifying question. For example:

| Patient: | “I don’t know whether I should take the chemotherapy treatments the doctor wants me to have.” |

| Medical assistant: | “You seem worried about the treatments. What are you concerned about specifically?” |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree