Chapter 3 1 Identify components of communication. 2 Define groups and components of group structure. 3 Identify and give examples of different group models. 4 Identify the stages of group development. 5 Discuss methods of establishing rapport within a group. 6 Explain how to plan and lead an effective occupational therapy group. The interpersonal relationship and the communication between an occupational therapy practitioner and client are important factors for satisfactory intervention outcomes. Knowing how to treat a client requires more than knowledge of the client’s medical diagnosis and treatment protocols; an understanding of personal psychosocial, environmental, cultural, socioeconomic, and occupational factors affecting the client’s level of function is also required. The practitioner must be able to communicate effectively to gather this information and a positive interpersonal relationship facilitates the therapeutic process. Good communication is a key factor in establishing the interpersonal relationship. Therapeutic use of self is also an essential element in the interpersonal relationship and will be addressed in Chapter 4. Components of verbal communication include written and spoken words. In both instances, the practitioner considers the characteristics of the audience. For written communication, the reading and comprehension levels of the reader should be assessed. Plain-language literature suggests that verbal communication be written at a sixth-grade comprehension level. Some clients may be embarrassed at their inability to read and may not wish to disclose this to the practitioner. Careful observation of the client’s skills is necessary to ensure that any written information provided to the client is appropriate. Practitioners should consider the use of simple explanations of health information versus medical jargon to ensure understanding in both written and verbal communication. They must be aware of the client’s environment and influence of culture, spiritual beliefs, and socioeconomic status. These influences may affect the ways health information and treatment are perceived by the client. Components of nonverbal communication include eye contact, facial expression, and body language such as positioning of self and use of gestures. Looking the client in the eye conveys interest and attention to the conversation. Consistently looking away from the client and demonstrating behaviors such as frequently checking the time indicate a lack of interest and caring. Facial expression should be consistent with the verbal message being provided. Smiling when talking about a serious topic is not appropriate and it does not portray compassion. Body language should be appropriate to the situation as well. Placing your hand on the client’s arm when he or she is speaking or providing a hug can be comforting to a client coping with the stress of illness or injury (Table 3-1). A group can be defined as individuals who share a common purpose that can be attained only by group members interacting and working together.4 All occupational therapy groups can be described as consisting of content and process. The content of a group includes the occupational activity that the group completes during the group time and includes what is said, written, or produced during the course of the group. The process of a group refers to the manner in which the occupational activity is conducted and the emotional tone of the verbal and nonverbal content that occurs during the group. Although the occupational activity content of a group may remain constant for a series of groups, the process may vary greatly, depending on the interpersonal communication that occurs and the facilitation skills of the group leader during the group process. Occupational therapy practitioners have the opportunity to engage clients in a variety of different groups based on purpose, group goals, and setting. The theoretical basis for group design and the purpose of the group dictates how the group is structured and implemented. Occupational therapy groups may be classified into different categories: activity groups, psychoanalytic or intrapsychic, social systems, and growth groups.6 Schwartzberg, Howe, and Barnes write, “Activity groups are small, primary groups in which members are engaged in a common activity or task that is directed toward learning and maintaining occupational performance.”6 Activity groups can be further classified into six different types of groups as described by Mosey.5 These include evaluation, task-oriented, developmental, thematic, topical, and instrumental groups. Evaluation groups allow for assessment of both interpersonal and activity skills. Task-oriented groups allow for the focus to be on both self-awareness and interactions with other group members through the activity process. Developmental groups focus on teaching group interaction skills that are considered developmental stage–specific. There are five stages, ranging from parallel groups in which clients work on individual projects in shared space to mature groups in which the group’s needs take priority over the individual’s needs. Thematic groups focus on the clients learning the knowledge, skills, and activities for a specific activity. Topical groups are similar to thematic groups, with the difference being the focus of implementing the group activity in the community. Instrumental groups focus on clients maintaining their current level of function and meeting health needs.5 Shatara is an occupational therapist who works in an acute psychiatric hospital on the adolescent unit. She provides group interventions to her clients. Shatara facilitates improved communication skills by having a small group of teenage girls make individual collages of their favorite activities. Although the teenagers are making individual projects, all of the materials and supplies to make the collages are shared. There is one pair of scissors, one glue stick, and only three magazines available during the group activity. Each client explains her individual collage at the end of the group session (Figure 3-1).

Interpersonal Relationships and Communication

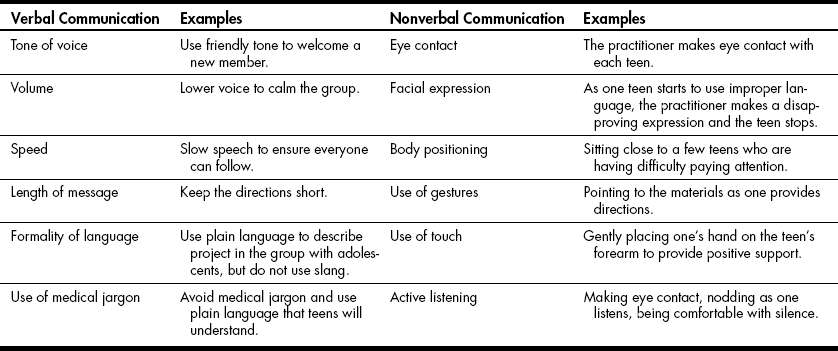

Components of Communication

Definition of a Group

Group Models

Activity Groups

Psychoanalytic Groups

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Interpersonal Relationships and Communication

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access