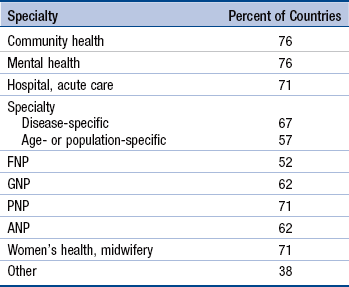

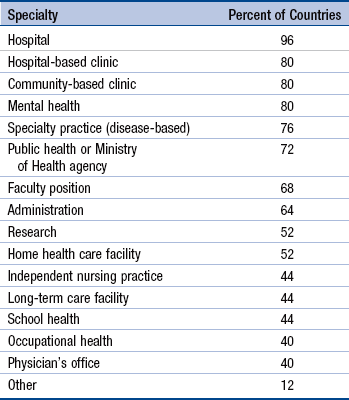

Chapter 6 International Evolution of the Advanced Practice Nurse Advanced Practice Nurse Issues Worldwide Power Differential Between Nursing and Medicine Lack of Physician Support for Advanced Practice Nurse Roles Level of Educational Preparation Valuing Clinical Practice Expertise Infusing Evidence into Role Development Health Care Delivery System Values Advanced Practice Nurse Payment Advanced Practice Nurse Regulations and Standards High-Quality, Interdisciplinary, Advanced Practice Nurse Education Looking to the Future: What Do We Have to Learn From Each Other? Advanced practice nursing has evolved in the international arena over the last half-century. With an initial focus in the United States, advanced practice nurse (APN) roles are now becoming more visible as a response to improving health care for people in all parts of the world. Internationally, health care problems have rapidly evolved from a major focus on deadly diseases, high infant mortality, and maternal morbidity to a new focus on chronic or noncommunicable diseases, an aging population, and lifestyle choices that promote health (Skolnik, 2008). Many areas of the world, such as sub-Saharan Africa, continue to have dire health care problems with communicable diseases and mortality, but managing chronic diseases and promoting healthy lifestyles have eclipsed infectious diseases worldwide as infant and child mortality rates have begun to drop globally (Liu, Johnson, Cousens, et al., 2012; World Health Organization [WHO], 2011). Child mortality has decreased to a point that some of the poorest countries are projected to meet Millennium Development Goal 4 for reducing child mortality (Demombynes & Trommlerova, 2012). Many countries are realizing that their aging population will have very different needs in the future and are gearing up to meet the chronic health care problems that accompany aging. Maternal mortality which was a huge problem in parts of South America and Africa, has begun to resolve itself with a greater emphasis on population control and women’s health (Grady, 2010; Hogan, Foreman, Mohsen, et al., 2010). Nurses have played a key and relatively independent role in providing health care in rural areas, particularly in parts of Africa and Australia, where major physician shortages exist. Increasingly, these nurses are entering programs that educate them for role expansion. As the incidence of chronic diseases increases, nurses and APNs will have an even greater role to play in managing these problems and educating the public on lifestyle issues. Other issues, such as the global health worker shortage and mass migration of health care workers to more developed countries, are important drivers of continued gaps in care. Along with these shortages are huge inequities of care across the globe, with some urban areas having an acute oversupply of providers and excellent health care facilities and others with desperate inequities and shortages of care. Economic disparities have increased over the last 30 years and this rate has accelerated with the recent worldwide recession, starting in 2008 (Leach-Kemmon, Chou, Schneider, et al., 2012). APN educational programs have also been developing in many areas of the world and, as these programs increase, the nursing workforce will be better prepared to function with advanced nursing knowledge. Recently, the World Health Organization (WHO) (2010) issued an important report underscoring the need to enhance the global nursing and midwifery workforce. There are several definitions of advanced practice nursing. The definition used in this text (see Chapter 3) states that “Advanced practice nursing is the patient-focused application of an expanded range of competencies to improve health outcomes for patients and populations within a specialized clinical area of the larger discipline of nursing” (see p. 71). Key elements of the definition are required graduate education and APN certification and the identification of seven core competencies, which distinguish APN-level practice regardless of role. The four specific APN roles used in this book are those used in the United States—nurse practitioner (NP), certified nurse midwife (CNM), certified registered nurse anesthetist (CRNA), and clinical nurse specialist (CNS). These different roles, as they are being developed in a global context, will be discussed later in the chapter. The International Council of Nurses (ICN)–International Nurse Practitioner/Advanced Practice Nursing Network (INP/APNN) definition states that “A nurse practitioner/advanced practice nurse is a registered nurse who has acquired the expert knowledge base, complex decision-making skills and clinical competencies for expanded practice, the characteristics of which are shaped by the context and/or country in which s/he is credentialed to practice. A master’s degree is recommended for entry level” (ICN–INP/APNN, 2012). Although some notable similarities exist among definitions, particularly in acknowledging competencies, expanded practice, and recommending graduate education, the ICN definition is general and recognizes that the terms nurse practitioner and advanced practice nurse are used interchangeably in some parts of the world. This definition incorporates nurse practitioner and advanced practice nurse into one definition to reflect a broad interpretation of APN roles as they are applied in different countries. This definition advances educational expectations by recommending a master’s level education, an important milestone for achieving advanced-level practice. When looking at the four APN roles from an international perspective, it is apparent that each of the roles is evolving with country- or region-specific differences. More time is needed to move to the standardization of roles, titles, and responsibilities for the various APN roles internationally, but this work is clearly beginning with a focus on competencies and scope of practice rather than on specific titles (ICN, 2009; ICN–INP/APNN, 2012). All these roles are discussed in detail in other chapters; this section will emphasize the international evolution of APNs. The NP had its origins in the United States and has had more than 45 years to develop as a primary care specialty, with additional foci on specialty care and acute care. In other countries, such as the United Kingdom, the NP role is at best 20 years old and is still developing, having evolved from routine well or primary care to the management of more complex specialty conditions in the context of an interdisciplinary team (Sibbald, Laurant, & Reeves, 2006). The United States and United Kingdom often serve as models for the evolution of the NP role. In Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, the use of a specific nursing title is restricted to those who have met certain requirements to practice. Also, in these countries, national standards for the regulation of and education for the role are becoming well developed and NP prescribing is regulated (Canadian Nurses Association [CNA], 2008; Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia, 2011; Nurse Practitioner Council of New Zealand, 2012). Although there are also NPs in England, both in primary care and specialty care, variability exists as to the level of education and prescribing abilities; nurses in general who have specific education can prescribe drugs from the British formulary (Kroezen, van Dijk, Groenewegen, & Francke, 2011). To add to the variability, some countries do not use the term nurse practitioner. In the Netherlands, the term nurse specialist has recently been adopted, replacing the NP title with five recognized specialties—intensive care, acute care, chronic care, mental health care, and preventive care (Frauenfelder, 2012; see Exemplar 6-1). In other countries such as in Singapore, the term advanced practice nurse is used instead of NP and is generally preferred. In Singapore, APNs initially function in hospital settings and some outpatient facilities or polyclinics in the community (Mei, 2012; Schober, 2012; see Exemplar 6-2). The survey by Pulcini and colleagues (2010) also identified the most common types of NP-APN specialties. This survey used the term NP-APN but was intended to survey NP roles, listed in Table 6-1. Table 6-2 indicates the most common types of positions held by NP-APNs from the survey. Specialties (Types) of NPs and APNs* *Survey of NPs and APNs educated in 21 countries. Adapted from Pulcini, J., Jelic, M., Gul, R., & Loke, A.Y. (2010). An international survey on advanced practice nursing education, practice and regulation. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 42, 31–39. Most Common Types of Positions Held by NPs and APNs* *Survey of NPs and APNs in 25 countries. Adapted from Pulcini, J., Jelic, M., Gul, R. & Loke, A.Y. (2010). An international survey on advanced practice nursing education, practice and regulation. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 42, 31–39.

International Development of Advanced Practice Nursing

Definitions

International Evolution of the Advanced Practice Nurse

Nurse Practitioner

![]() TABLE 6-1

TABLE 6-1

![]() TABLE 6-2

TABLE 6-2

International Development of Advanced Practice Nursing

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access