At the extreme left of the continuum is the model we mentioned above that views healthcare delivery from a unidimensional perspective. Physicians make decisions, tell others what their roles and duties are, and expect orders to be carried out without exception. As a more traditional model of care, this is often observed in physicians’ offices where other members of the team are direct employees of the team leader (physician). Communication is often one-way and any sharing of decision-making is operationalized by the physician asking questions about conditions, lab results, or medication protocols.

A multidisciplinary approach to healthcare takes into consideration the expertise and experience of several healthcare professionals with an understanding that multiple viewpoints are possible. With this model it is still very likely that one individual, again usually a physician, makes most of the decisions and communicates her desires to other members of the team. Unlike the unidisciplinary model where the physician assumes an omnipotent role, input from other team members is likely to occur with some regularity. The extent to which the physician acts on such information and acknowledges it as a valuable contribution still remains her prerogative.

A third option is the popular interdisciplinary team model. Occupying the middle part of the continuum, the interdisciplinary team approach stresses the importance of each team member’s contribution and strives to develop coordination and harmony among the diverse members of the team. The notion of coming together for the good of the patient is an important one to the interdisciplinary team, although ensuring the implementation of multiple approaches to care based on different medical disciplines can be challenging, if not problematic, with this approach. In some instances such teams find themselves in competition for the medical plan designed for the patient. Elements of negotiation and emergent leadership are observed. Ultimately, if the team experiences indecisiveness, a physician or charge nurse will intervene to make a unilateral decision on behalf of the patient.

Transdisciplinary teams are different from interdisciplinary teams in that they adopt more of an amalgamation model, where medical care emphasizes not so much the delivery of nursing, medicine, therapy, or other healthcare professional discipline as a blended approach that identifies the needs of the patient from a consultative and problem-solving perspective. Interdisciplinary teams evolve into transdisciplinary forms when team members develop trust among their colleagues and begin to share authority, responsibility, and expertise with other members (Wieland et al., 1996). In essence, the interdisciplinary effort becomes transformed into an integrated team working for the good of the patient rather than insisting on strict disciplinary influence. Clearly, effective and responsive communication is a key determinant for moving healthcare professionals into this transformative state.

At the other end of the continuum is the synergistic team. Like the transdisciplinary team that assumes a shared decision profile, this team model makes every effort to ensure that decisions not only involve the participation of all members of the team but that they are patient-centered. A synergistic team approach is not a common model for healthcare organizations, yet it offers the greatest opportunity for patient health and safety (Lee, 2010). In the next section we explore what a synergistic team is like and how it can succeed in highly complex healthcare organizations.

Model of Synergistic Healthcare Teams

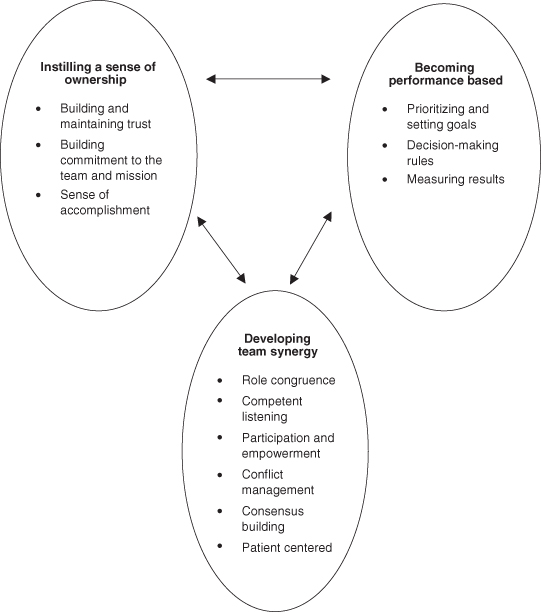

Synergistic healthcare teams offer the greatest potential for improving patient outcomes and elevating organizational and system efficiency (Farr & Ames, 2008). Synergistic healthcare teams have three essential elements: (i) instilling a sense of ownership; (ii) becoming performance based; and (iii) developing team synergy. Marginalizing any one of these elements will limit the effectiveness of the team effort (see Figure 11.2). Let us look at each of these elements in turn.

Instilling a Sense of Ownership

Rosabeth Moss Kanter suggests in her book Evolve! (2001) that effective teams distinguish themselves from ineffectual ones through a feeling for and commitment to the greater good. Effective teams are those that take on a sense of ownership for the things they do, the decisions they make, and the ways that they feel. Medical teams are often under enormous pressure and find intrinsic fulfillment from personal accomplishments in delivering care. Personal achievement is critical to building confidence in oneself. However, the key to building effective, synergistic teams is inculcating a sense that what one does is part of a greater purpose that integrates personal goals into the good of the team and the patient. Accomplishing three goals instills this sense of team ownership: building and maintaining trust, building commitment to team and mission, and realizing a sense of accomplishment.

Building and Maintaining Trust

Drawing together a collection of healthcare professionals does not ensure a sense of devotion to the team or the care it delivers. This is especially true when team members hail from diverse backgrounds, groups, and locations (Rees, Edmunds, & Huby, 2005). Having confidence in each member of the team is a challenging but necessary component of synergy. Trust is a key ingredient in developing ownership of the team (Smith & Cole, 2008). Trust comes in multiple forms. Trust in the group is the hope, belief, and confidence of team members that what is said and done in the group is both meaningful and appropriate. Team members expect that their efforts count for something. Trust in team colleagues comes from a history of communication that is open, sincere, and consistent. Team members trust those who are willing to say what they mean, have something valuable to say, and understand that what is said is honest and forthright. Team communication must ensure high levels of trust throughout the team process.

Trust can also be facilitated by:

- demonstrating that you do what you say and mean what you say;

- acting consistently;

- a willingness to listen to others and defer to their judgement;

- sharing information and asking for help;

- avoiding favoritism;

- disclosing personal things about self;

- acknowledging others’ skills and talents (Kinlaw, 1991).

From these processes comes a greater sense of mutual respect for one another that promotes trust in teams, a key ingredient in acting on the patient’s behalf in the absence of direct evidence. Teams must understand one another and develop mutual respect (O’Brien, Martin, Heyworth & Meyer, 2009). For example, if a charge nurse on a midnight shift reads a patient chart indicating the removal of oxygen therapy after two hours, she must have trust in the respiratory therapist in order to comply if her experience tells her to leave the oxygen in place.

Building Commitment to Team and Mission (Vision)

It is entirely possible that team members trust one another and still lack a strong commitment to the team and mission of the healthcare organization. Teams that exist primarily for social reasons are a good example of this phenomenon. To instill ownership in a healthcare team, commitment to the team and mission must also be present. Commitment is a state that reflects team members’ willingness to care personally for the team and its members and to maintain a dogged determination to help the team succeed. This type of commitment is developed primarily through explicit clarification of the vision and mission entrusted to the team (O’Hair & Wiemann, 2012). Communication skills must include persuasive efforts to convince team members of the importance of the mission and vision, and providing feedback about how their efforts are making a difference within the larger organization. From this communication, team members come to assume a greater sense of identity with the team which can often become the focal point of their behaviors. Commitment can additionally be demonstrated by:

- caring personally about the team and its success;

- loyalty to the team, its members, and their mission;

- remaining focused on the team’s mission and goals of patient care;

- maintaining high intensity levels for the team’s efforts;

- demonstrating to others positive attitudes about the patient, organization, and healthcare in general;

- asking for commitment from other members of the healthcare team;

- taking pride in being part of the well-being of the patient (Kinlaw, 1991).

Once in place, commitment becomes easier to maintain because it is self-perpetuating through the sharing of common goals and a sense of needing one another to ensure positive health outcomes.

Sense of Accomplishment

Healthcare professionals choose their profession for a multitude of reasons, but seeking a sense of accomplishment is an important goal. The feeling of contributing to the well-being of patients is more than a cliché. It is a sensation that rewards and motivates team members to assume ownership of the healthcare team. Not unlike sports teams who reach beyond normal expectations, healthcare teams take great pride in their accomplishments, whether large or small. It should be noted that team members can experience satisfaction with their own individual efforts as a team excels. It is that type of self-efficacy that causes healthcare professionals to seek additional experiences. However, experiencing a sense of team accomplishment can transcend even personal triumph precisely for the reasons teams exist—accomplishing more than individuals can. Taking ownership of team accomplishment feeds on itself and becomes a symbiotic experience for all involved Zismer, 2011). Inculcating a sense of accomplishment in team members can be achieved through:

- identifying and celebrating positive patient outcomes;

- demonstrating how the team is improving the healthcare organization;

- recognizing individual achievement within the context of team success;

- collective responsibility—holding the entire team accountable for its level of success.

It is through these levels of accomplishment that team members are able to address lingering uncertainties facing them during stressful times and understand that the team stands ready to offer encouragement and facilitation when the occasion arises.

Becoming Performance Based

Effective healthcare teams are those with an understanding that their performance counts and will be measured and rewarded accordingly. Not all rewards come in tangible ways, and teams do not necessarily anticipate that to be the case. However, what teams should expect is that their performance contributes to patient care and can be measured according to some acceptable standard (Zismer, 2011). Three key factors are essential to instilling a performance-based team-building structure in healthcare organizations: prioritizing and setting goals, measuring results, and instilling strong decision-making procedures.

Prioritizing and Setting Goals

A first rule of thumb for basing a team’s effort on its performance is through a process of goal setting. Teams must be allowed to take their charge from the office, clinic, or hospital and then prioritize and develop goals that are tangible, meaningful, and performance based. Some hospitals institute team-based structures to facilitate the collective management of patient care. Some of these contexts are more successful than others in developing the types of goals and the needed support to accomplish these goals. Besides setting the benchmark for success, goal setting/prioritization serves to focus team members’ efforts on specific patient or organizational objectives, gives them a sense of direction, and helps them persist in their labors. One of the greatest concerns of hospitals, clinics, and long-term care facilities is patient safety. A mantra in healthcare, especially the facilities in which patients are cared for, is that they should do no harm to patients. Unfortunately, thousands of patients die each year in healthcare settings due to medical errors, poor safety practices, and ineffective coordination of patient care. For that reason healthcare organizations ask their teams to include patient safety in their goals for overall patient care.

Research has demonstrated that performance is enhanced when goals are specific, exciting, lofty, and prioritized (O’Hair, Friedrich, & Dixon, 2011). It is also important for teams to develop goals that allow some acceptable level of flexibility in their implementation and measurement, allowing for contingencies. Other strategies to keep in mind, according to O’Hair, Friedrich, & Dixon (2011), include the following:

- Goals should be problem based, not value based. Values are important, especially ethical values, but they must be practical and relevant and should explicitly state how they can be incorporated into immediate patient care.

- Teams should set performance standards. How will the team know that it succeeded? Is length of hospital stay a good criterion? Is the control of pain a preeminent concern over a persistent physical therapy routine? Teams have to come to terms with diverse patient priorities.

- Resources needed to accomplish goals (time, space, funds, etc.) should be identified. Generally, healthcare organizations are not going to volunteer resources without some driving impetus. Teams have to be ready to make credible requests for resources in order to accomplish their goals.

- Teams will always need to recognize contingencies as they arise. Patients in critical care units will require adaptive plans for their care. Do all members of the team understand and interpret the goals and plans for the patient in a way where adjustments can be made with immediate notice?

Measuring Results

Teams have a professional obligation to monitor and report their progress. Teams are in constant need of valid and consistent information flows to effectively manage patient care (Demiris, Washington, Oliver, & Wittenberg-Lyles, 2008). Here we are not focusing on patient progress per se. That is accomplished through discharge reports and review committees. Instead, members must gauge their own performance as a team and how the activities of the team have contributed to positive outcomes. Therefore, teams must systematically assess their goals. It should be left up to the team how their results are measured, so long as they are accountable to the organization and the mission and vision of the team (Lee, 2010). Unfortunately, this is not always promoted in some healthcare organizations. Regardless, measurement or assessment techniques will vary according to the goals prioritized by the team, but should certainly include many of the standard criteria used for assessing performance. The key issue is that team members understand and appreciate the fact that their efforts are being measured on a systematic basis. The following guidelines are important:

- Results should be understood and accepted by the team.

- Results should be measured against the goals set by the team. Should goals be revised?

- Results should be compared to the mission of the organization.

- Results could be compared against other teams in the organization.

- How does the team feel about the results? Does it have a sense of accomplishment?

- How does the team feel about its level of commitment to the team and the mission?

- Were expectations set at the appropriate level? Were expectations violated?

- Do team members have confidence in themselves?

- Do team members seem to care about each other?

- Were facilitation efforts effective?

- How effective was the creative problem-solving process?

- How efficient was the group during its deliberations?

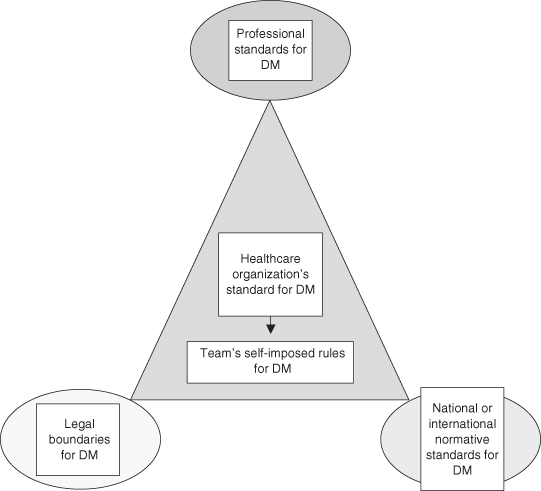

Decision-Making Procedures

Developing, understanding, and adhering to a set of rules for making decisions on patients’ behalf comes under intense scrutiny from various sources within the organization. As an end point for just about everything that comes before it (analysis, assessment, evaluation, judgement), decision-making is influenced at every conceivable level (Koopman, 1998). Disciplinary norms influence how professionals make decisions, as do legal statutes and normative standards set by courts. The healthcare delivery system itself may weigh in on how decisions should be made in certain contexts (“do no harm,” “do not over-medicate”). The healthcare organization where professionals practice no doubt has stipulations regarding certain decision-making rules and the team itself may impose decision-making rules that apply to its own activities. Figure 11.3 offers a simplified glimpse into how involved and potentially complicated decision-making procedures and stipulations can permeate the actions taken by healthcare teams. Taken together, this system or culture of rules for decision-making offers important implications for team members, especially when decision rules appear to conflict.

Similar to other organizations, healthcare facilities have a tendency to influence decisions on lower units such as teams. A key reason behind this influence involves the focus on liability and litigation. As members of an organization, teams are afforded a reasonable degree of protection from legal implications through protection from their healthcare organization and from their own personal malpractice insurance. Hospitals may carry their own insurance or choose to self-insure, but regardless of their preferences they have a great deal at stake in how decisions are reached by healthcare teams. Therefore, healthcare organizations have a role in the process that becomes manifested through decision rules that protect them from negligence. Like teams, organizations develop a strong sense of normative standards for decisions through environmental scanning (Sutcliffe, 2001) in order to avoid exposure to litigation claims based on unusual practices. Once normative and standardized guidelines are put in place for teams, it is the teams’ own responsibility to develop rules for decision-making. These rules will vary according to the type of care they are delivering (e.g. acute, long-term palliative) and the composition of the team. However, some general guidelines based on the functional perspective (Gouran & Hirokawa, 1996; Hirokawa & Salazar, 1999) can be offered here to facilitate how teams make decisions (Dewey, 1933; Gouran & Hirokawa, 1999; O’Hair, Friedrich, & Dixon, 2011).

Problem Identification

Not all medical conditions confronted by the medical team can be readily surmised. Unfamiliar symptoms or unexpected complications can create doubt about how to define the medical condition of a patient. Teams have much at stake in correctly identifying the condition and agreeing upon its etiology. Discussion and analysis will usually be required to make any conclusions about the medical problem. As much as possible, teams should be in solid agreement about the problem before moving to the next step.

Clarifying Parameters and Criteria

Teams will often move to subsequent steps after problem identification because time is short and deciding on a treatment regimen is an important intervening step in the process. However, teams need to ensure that they have adequately deliberated over what will constitute the standards by which they judge their decisions and the rules they will apply. In a cancer diagnosis, the team will want to set standards for care based on how the disease progresses and determine at what point aggressive treatment is continued or discontinued in favor of palliative care. It is better to make these decisions early on as guideposts rather than wait for symptoms and conditions to present, creating emotional conflict over treatment.

Generating Alternatives

Teams have the advantage of being able to generate some creative options for medical care. Sometime known as “risky shift” or group polarization (Myers & Lamm, 1976; West, 1998), teams have a tendency to move away from neutral, normal, or expected alternatives toward decisions that are more extreme or unusual. Teams generate a sense of confidence that reduces their inhibitions to try something new. This can be good or bad. Innovative treatment options can save lives and reduce suffering for patients—when they work. Alternative treatment options that steer too far from the normal should probably come under the scrutiny of an outside party before moving forward (see the next phase). The point here is that as the touchstone phase for team decision-making, groups need to consider the opinions of all team members (including the patient) and to avoid being reticent in advancing strong and creative alternatives (Lee, 2010).

Evaluating Alternatives

As an equally important step, team members must be ready to step up and offer their considered opinion about all of the alternatives generated by the prior step. It is within this phase that the ingenuity, care, and safety of the alternatives are carefully analyzed. Advantages and contraindications of all treatment alternatives should be exposed and weighed, and it is in this step that a diversity of team members can bring critical knowledge to bear on the options being tested. The best available evidence (referred to as evidenced-based medicine) should be applied to the alternatives and tested for strength. For example, a young patient with a protrusion on his midriff is being examined for the possibility of a tumor. Imaging has not reached a conclusion about the mass and two team members argue for the normal protocol of outpatient but invasive surgery to determine if the mass is malignant. Another team member argues that, based on the patient’s age, it would be better to conduct a positron emission tomography (PET) scan to determine if the growth is more cyst-like. A previous research article this team member read argues for the likelihood of such a mass and that further imaging would be less risky than surgery at this point.

Selecting the Best Option

In the previous case, a consensus may not be achieved among all team members. It is important that sufficient analysis and deliberation be pursued before reaching a final decision. Obviously, some medical conditions require a more rapid decision, such as in emergencies. In cases such as these it is likely that the physician will consider as much information and as many perspectives from the team as possible and then make a unilateral decision for care. When more time is available, generating as much agreement as possible for the treatment protocol is critical for several reasons. First, the evidence and experience that can be brought to bear in the case, the more likely it is that an option will be more valid. Second, team members want to know that what they are doing for the patient was a result of their input; they feel more invested in the decisions derived for the patient and develop that sense of ownership discussed earlier. Ultimately, a decision is usually made by the team leader based on due deliberation. Seldom do teams vote on a treatment option; a consensus is preferred when time allows.

Implementing the Option

Putting the treatment option in place is much easier and teams have more confidence when all of the previous steps to decision-making have been followed. Many of the details and loose ends associated with treatment have been previously considered and steps for successful treatment have been laid out. The team will want to consider the most efficient pathways for care and develop a plan for implementation. As with any team-based decision involving complex processes, alternative options considered as part of the decision-making process must be kept in the background for handy reference should the original option fail the team. That is one of the more important reasons for arriving at medical decisions through a team-based format. Second- and third-place choices suggested by the team can be moved into place with confidence.

Evaluating the Results

Teams can learn as much from their failures as they can from their successes. One of the hallmarks of effective team deliberation is taking advantage of hindsight as a learning tool. Known by many labels (after-action reviews, patient outcome reports, etc.), the process of understanding what worked and what didn’t is invaluable to healthcare team members. Questions can be directed toward the evidence-based process of diagnosis and generation of alternatives. Did the systematic process of problem-solving work? Were some steps weaker than others? Was there a disconnect between the decisions reached by the team and the manner in which the treatment was implemented? How could the process have been improved? Teams have a functional and professional responsibility to bridge the gap between what occurred and what could have been better accomplished.

Developing Team Synergy

Group synergy is the phenomenon of groups performing in ways that reach beyond the collective efforts of individuals. “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts” is the typical phrase used to characterize group synergy. Group synergy is composed of role congruence, competent listening, participation and empowerment, conflict management, consensus building, and being patient centered.

Role Congruence

Other problems within the team can lead to unsatisfactory outcomes. Role confusion as well as overlapping tasks and responsibilities can also inhibit interdisciplinary teamwork (Apker, Propp, & Ford, 2005; Berteotti & Seibold, 1994). Role congruence is important in terms of clarifying each team member’s role, tasks, and responsibilities, and these should be clearly discussed during initial team meetings. What is well to remember is that while healthcare team members retain and promote their disciplinary professional roles (occupational therapistss, nurses, pharmacists, etc.), they are also very likely to take on team-based roles as well. Who is expected to set up meetings as needed? Who will act as the facilitator of the meetings? Who will be responsible for recording the deliberation of teams? Who will be in charge of communicating decisions to other organizational personnel? Who is responsible for follow-up through the treatment regimen? Responses to these questions provide essential substance for ensuring that team-based decisions and actions are efficient and complete.

Role congruence also involves the ability of members to suspend their personal inclinations for the good of the team. Roles are powerful forces in promoting an individual’s identity in a professional organization. Identity is a key motivating force for why people behave in certain ways, and identity is all too often wrapped up in the specific roles medical professionals expect themselves to play (Lingard et al., 2006). When team members consider that their knowledge and expertise are intrinsically valuable to the patient and the team while at the same time perceiving that what they bring to the table is an integrated piece of the puzzle, it is easier to move toward role congruence that emulates synergy rather than unidisciplinary efforts (Lee, 2010).

Competent Listening

Teams will succeed or fail based on their communication skills. In a way, all of the components of group synergy are communication based (Norris et al., 2005). However, championing the use of competent listening skills is clearly key. Listening is one of the most overlooked skills of team members and facilitators. As Stephen Covey said in his Seven Habits book (1986), seek to understand before you attempt to be understood. Make the effort to understand not only what a person is saying, but also why they are saying it (what are their true intent and motivation?). Try to understand their feelings. Determine whether they are communicating from a professional or a team-based role. Ask questions if you are unsure (“I am not sure I understand …”). Increase your tolerance for listening to others. Respect their input to the group. Give responsive nonverbal feedback when you are listening (nodding, eye contact, forward lean, etc.) (O’Hair, Friedrich, & Dixon, 2011).

Approachability gives team members the impression that you are open and accessible to their ideas and opinions. Effective listening is one way to demonstrate approachability, as is an accessible nonverbal demeanor (smiling, eye contact, open body orientation, etc.) (Romig, 1996). Approachability can also be established by asking for opinions, commenting on ideas, and expressing positive regard for groups or team members.

Participation and Empowerment

Medical teams do not automatically enjoy engaged, active, and creative participation. It takes clever facilitation skills to keep the team going and on track. Beyond the normal questioning and responding, team members must probe, nurture, and encourage one another. In addition, it is important to stand ready to handle various dysfunctional roles that team members have a tendency to adopt.

Asking Questions.

Nothing is more important for team functioning than asking good questions. The following constitute some good rules for asking effective questions (O’Hair, Friedrich, & Dixon, 2011):

- Begin questions with “Who,” “What,” “Where,” “When,” and “How.”

- Avoid questions requiring a yes or no answer.

- Ask questions that focus the medical team on the issues at hand (goals, mission).

- Phrase questions positively. Try not to be confrontational.

- Use secondary questions for elaboration or clarification.

Responding/Feedback.

One of the most effective ways to keep the discussion going is through effective responses or feedback. Responding is best accomplished through the following strategies:

- Paraphrasing: translating responses through summarizing, recapping in your own words.

- Evaluating: judging the effectiveness and appropriateness of responses in a constructive manner.

- Supporting: reassuring, encouraging, and sustaining responses of others.

- Probing: seeking additional information, provoking additional discussion.

- Interpreting: offering your own meaning (interpretation) for what someone has said.

Managing Participation Styles.

Team members will not come to the table with similar inclinations and skills. Participation styles can be managed through effective facilitation skills (O’Hair, Friedrich, Wiemann, & Wiemann, in press). Examine the team communication styles that facilitate participation in Table 11.1.

Table 11.1 Team communication styles that facilitate participation

| Style | Description | Facilitation |

| Rambling | Much discussion except on the subject. Loses the point. | Raise hand slightly, get floor, refocus attention on the issue. Glance at watch. |

| Verbose | Excessive talkativeness, anxious to show off, very wordy. | Ask difficult questions to slow them down. Ask others to interpret the meaning. Ask for additional input. |

| Inarticulate | Can’t put thoughts into a coherent form. Can’t express themselves. | Paraphrase their comments. Ask others if they feel the same way. |

| Sidebar conversations | Two people talking privately during team discussion. | Call one by name and ask for their feelings on the discussion. |

| Avoiding | Noninvolvement, little participation. | Call on them by name. Ask for opinion. |

| Blocking | Indulges in negative or disagreeable comments. | Ask why they feel that way. Have them compare their view to the others. |

Conflict Management

All teams will experience some level of conflict, and the success of interdisciplinary healthcare teams can be undermined by conflicts between different team members. Within any healthcare team, members will vary in terms of their social status and power. For example, physicians tend to have a higher social status and more power within healthcare organizations than nurses or social workers. Power differences may lead team members with less power to become apprehensive and contribute less to the group discussion. When this happens, ideas that may be beneficial in terms of treating the patient or meeting his or her needs may be lost. Power disparities can also lead to resentment among team members and impede successful collaboration (Abramson & Mizrahi, 1996).

Conflict between team members can arise in interdisciplinary teams for a variety of reasons, such as when people are not satisfied with the team discussion, if they feel that their viewpoint is being disregarded by other members, or because of personality differences (Bennett, Gadlin, & Levine-Finley, 2010). Conflict can also be productive or unproductive. Conflict can lead to differing viewpoints about the nature of a problem, a healthy discussion of competing options for treating a patient, better-informed decisions, and reduction of oversights and redundancies that can be costly to the patient’s health or the healthcare organization. Sometimes interpersonal conflict occurs due to personality differences and sometimes it is content oriented. Regardless, here are five steps to take to management conflict productively: (i) openly state the cause of the conflict (is it personality based or differences of opinion?); (ii) discuss the goals of those in conflict; (iii) probe for areas of agreement; (iv) discuss means of resolving conflict through consensus; (v) make a decision (O’Hair & Wiemann, 2012).

Consensus Building

Diversity of interests and styles in the team is a strength. Without diversity, there is no reason to form teams and individuals can be left to make decisions. Bringing diverse ideas to a consensual decision, however, is a challenge. One method of consensus building is through the process of normalizing norms. All groups will develop norms (regularized practices, behaviors) over time. Some are effective and others are not. Most experts agree that it is best to establish certain norms from the beginning of the group’s existence. In this way, groups understand early on the ground rules for their deliberations. As a facilitation strategy, the first few sessions can begin by stating and agreeing on appropriate norms (e.g. being on time, turn-taking, no excessive speeches, no hostile remarks, active participation).

Coordination and collaboration among team members is also an ideal way to build consensus. Building upon one another’s ideas, being supportive of the creative process, and engaging in reasoned skepticism contribute to consensus building. In addition, the following steps can be taken to reach consensual decisions in teams (O’Hair, Friedrich, & Dixon, 2011):

- Encourage team members to concede their personal positions when they are illogical or unworkable.

- Maintain an open mind about constructive conflict. Conflict can lead to better decisions when handled professionally. Use conflict to guide the team to a few remaining positions.

- Unless pressed for time, avoid voting or averaging as a means for decision-making.

- During stalemates, identify issues common to all positions and combine them into one integrated idea (decision)—known as the common-denominator rule.

For many people, team efficiency is a top priority among their “issues” concerning groups. Teamwork is often perceived as busy work or lost time, especially when team members have other responsibilities in the organization. Facilitation efforts that maintain an efficient team process are highly valued and contribute to consensus building. Consider the following steps to increasing efficiency in teams.

- Set an agenda and stick to it. Effective agendas are time bound (each item has a deadline associated with it).

- Employ a time monitor (timekeeper) to keep the group on track.

- Consider rules for participation (no speeches, comments to be one minute or less, etc.).

- Build in a reward system for maintaining efficiency.

- Do not hesitate to confront and challenge members when instances of inefficiency are observed.

- Demonstrate an energized level of communication as a model for efficient teamwork.

Patient-Centered Focus

Patients can also play a role in a synergistic team approach to healthcare, and many teams include the patient and/or his or her significant other(s) as team members (Poole & Real, 2003). Rather than being passive recipients of instructions and medications from their providers, healthcare teams should educate patients about the biological and psychological implications of their health issues and the various treatment options available to them (Coopman, 2001). As a form of patient agency (O’Hair et al., 2003), including patients in the process of decision-making can go a long way toward enriching the alternatives generated for care and investing the patient in the treatment regimen. As we have seen, allowing patients to become active and informed participants in their own wellness process maximizes the potential for successful treatment outcomes and patient satisfaction (Howe, 2006).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree