Background

On most surveys of general health status, residents of Mississippi rank at or very near the bottom (United Health Foundation 2009; The Commonwealth Fund 2009). In NMMCI’s service area, the prevalence and age-adjusted mortality rates for most chronic illnesses exceed statistics reported for the nation, as well as the State of Mississippi (Mississippi State Department of Health 2007; University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute 2010).

North Mississippi Health Services, the parent system of NMMCI, is one of the largest rural health systems in the United States. Approximately 61% of the residents of 24 counties in northeastern Mississippi seek high quality, cost effective health care services at one of the six hospitals and 34 clinics that comprise the health system. On average, 800 patients diagnosed with CHF are discharged annually from the health system’s community hospitals, and more than 2,900 patients diagnosed with CHF are active NMMCI patients. Due to their complex medical conditions and limited opportunities to learn disease management skills, these patients are at increased risk for complications and readmission to the health system’s hospitals.

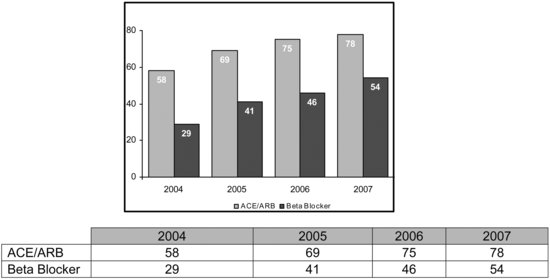

One of the most formidable challenges for NMMCI’s rural health care providers has been maximizing adherence to evidence-based standards of care for medical management of CHF. At the rural clinics, NMMCI’s information technology system generates electronic prompts for clinicians to review patients’ treatment plans for compliance with standards of care. Prior to project implementation, this technology, which was only operational at the point of care, yielded modest but inadequate gains in adherence to treatment guidelines for the use of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE), angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB) and beta blockers (Figure 24.1).

Moreover, because NMMCI’s rural clinics’ capabilities do not afford routine access to specialized standards of care for CHF, indicated procedures, such as echocardiograms, were not always completed. In response to this issue, NMMCI clinicians reviewed the peer-reviewed literature to develop plans to expand and strengthen the continuum of care offered to patients living with CHF in rural communities.

Project plan

The Chronic Care Model (CCM) served as a template for the Communities of Care for CHF initiative (Bodenheimer et al. 2002a; Bodenheimer et al. 2002b). The project also embodied key elements of care transition models. Drawing from the exciting work of Dr. Eric Coleman, a multidisciplinary team was formed to improve transitions across NMHS’ delivery system (Coleman et al. 2006).

Communities of Care for CHF focused on the clinic system’s most medically vulnerable cohort of patients diagnosed with CHF, those aged over 65 years. Programming was implemented at 22 NMMCI clinics, and the specific aims were:

- To improve compliance with American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association standards of care for CHF (2005).

- To improve clinical outcomes of rural patients through increased adherence to indicated medications.

- To increase knowledge and improve self-care skills of patients.

- To achieve a reduction from 21% to 15% in the 30-day all-cause readmission rate for CHF patients discharged from this hospital.

To achieve these aims, existing services were intensified, and new services were added at critical junctures in the care process.

Communities of Care for CHF relied heavily on development of a more robust clinical information system capable of monitoring patients closely and generating alerts to non-adherence beyond point-of-care interactions. A registry was created containing the names and contact information for clinic patients diagnosed with CHF and was populated with data specific to the standards of care (use of ACEs, ARBs, and beta blockers; echocardiogram results; and so on). The registry was also infused with health information technology capabilities that enabled the NMMCI performance improvement data analyst to query databases to monitor adherence to specific standards of care, hospital readmissions within the past 30 days, or emergency department (ED) visits for CHF-related issues.

Effort was also directed toward designing more informative discharge summary forms to distribute to CHF patients following their clinic visits. The redesigned CHF-specific discharge summaries enabled patients to review vital sign values; changes made in prescription medications; reminders regarding diets, physical activities, and check-up visits; and other individualized recommendations.

The continuum of care for rural patients with CHF was also made more robust by introducing specialized programming at clinic sites for the highest risk patients. Each month, the CHF disease registry was queried to identify patients non-adherent to standards of care; heavy utilizers of hospital, clinic, and ED services for CHF-related issues; and/or those with high-risk health indicators, such as elevated blood pressure, or high-risk health behaviors, such as smoking. In addition, individual providers in the community were contacted for assistance in identifying vulnerable patients. These patients received invitations to attend “CHF Days” at their local clinics, and clinic staff followed up with telephone calls to urge them to attend.

For each CHF Day event, an outcomes manager, CHF nurse educator, pharmacist, and cardiology technician traveled from the health system’s headquarters in Tupelo to spend the day at the rural clinics. The team reviewed clinic patients’ treatment plans and offered services consistent with standards-based care, such as echocardiograms, pneumonia vaccinations, nutrition counseling, and medication reviews. The pharmacist reviewed laboratory values and current medication regimens and made recommendations for changes in medications, diet, and/or behavior.

In collaboration with the patient’s primary care provider, recommendations formulated by the pharmacist and the CHF nurse educator during CHF Day events were synthesized into individualized treatment plans that were reviewed with patients during their clinic visits. As part of CHF Days, high-risk patients attended educational programs that lasted 30 to 45 minutes. Content focused on empowering patients to participate in the management of their chronic illness. Prior to leaving the clinic, high-risk patients were scheduled for check-ups with clinic physicians at three months or sooner, depending upon their medical status.

Registered nurses (RNs) employed by NurseLink, the health system’s call center that performs nursing triage services, served as the CHF Care Transitions Team’s outcomes and case managers. These RNs reviewed discharge records daily to identify patients diagnosed with CHF who were released from one of the health system’s hospitals to their next health care delivery site: home, home with home health, or assisted living facility. Within 48 hours of discharge, an RN contacted each discharged patient to reconcile medications, begin patient education, and confirm follow-up appointments. When discrepancies were noted in medications or no follow-up appointments were scheduled, CHF Care Transitions Team members urged patients to contact their primary care providers, gently “coaching” them to manage their own health issues. Home visits were scheduled for CHF patients for whom extended services were indicated, such as patients who were unable to name their medications over the telephone.

Preliminary results

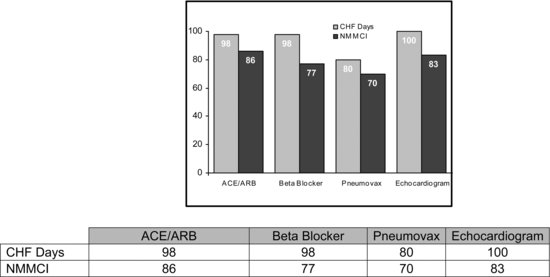

A total of 70 clinic patients participated in NMMCI’s Communities of Care CHF Days pilot project and all clinic patients with CHF who were discharged from hospitals in the NMHS health system were entered into the care transitions component of the initiative. The patient registry was used to track alignment with standards-based care and to monitor clinical outcomes. To measure project impact, patient data collected during the six months preceding CHF Day events were compared with data recorded six months post participation in CHF Day events. Although all participants have not yet completed the six-month follow-up phase, preliminary results are very promising (Figure 24.2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree