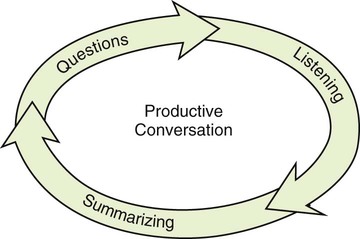

Chapter 7 Here are a few tips that can help new colleagues get to know you: * Do you have an unusual name? Be prepared to spell it and pronounce it clearly. Share a few details about its origin. Remember to be patient and keep a sense of humor if someone has trouble pronouncing or remembering a name that is new to them. * Say where you went to school, or share some of your work-related accomplishments. * Humor can break the ice. A mildly self-deprecating joke can make your new co-workers feel at ease around you. Of course, be sure to stick to appropriate humor. The three phases of a productive conversation are listening, summarizing, and asking questions (Figure 7-1). As a conversation deepens, you will often repeat these three phases. We’ll look closer at all three phases now. The listener propels the conversation by making gestures and interjecting to encourage the speaker to continue. Typical expressions for encouraging a speaker are listed in Box 7-1. Give speakers all the time they need to express themselves. You want them to say as much as possible, to unearth as much information as possible. As you listen, observe body language and assess the speaker’s emotions. The pause—a natural break in conversation—is a signal to change speakers and listeners. Never interrupt; wait for that pause. People who interrupt have already stopped listening. They have already decided what they want to say in response, even before the other person has completed her thought and paused. Even an encouraging interjection, like “Uh-huh,” should wait for a pause. If you speak after a pause, it shows that you were listening actively, especially if you make a logical comment, make an observation, or ask a relevant question. Then, once you pause, you have invited your partner to respond, and you can again encourage them to continue. Figure 7-2 shows two health professionals listening successfully to a patient.

Interacting Successfully

Take responsibility for the success of interactions between you and your clients and between you and your co-workers.

Take responsibility for the success of interactions between you and your clients and between you and your co-workers.

Uncover more information by being an active listener.

Uncover more information by being an active listener.

Listen to drive conversations forward.

Listen to drive conversations forward.

Recognize communication challenges related to people with disabilities or language barriers, and know what to do to solve them.

Recognize communication challenges related to people with disabilities or language barriers, and know what to do to solve them.

Use communication strategies to respond to diversity in the workplace.

Use communication strategies to respond to diversity in the workplace.

Become aware of the power of body language.

Become aware of the power of body language.

Empower your communication strategies with body language.

Empower your communication strategies with body language.

Listening Actively

Starting a Conversation

Introduce Yourself

The Listening Process

Listen

The Pause

Communicating With Special Groups of Clients

Learning Objectives for Communicating with Special Groups of Clients

Rapidly assess special communication challenges.

Rapidly assess special communication challenges.

Have strategies at hand to communicate effectively with hearing-impaired clients.

Have strategies at hand to communicate effectively with hearing-impaired clients.

Know how to gain the attention of people with hearing and visual impairments.

Know how to gain the attention of people with hearing and visual impairments.

Empathize with the needs of disabled people, so you can anticipate these needs.

Empathize with the needs of disabled people, so you can anticipate these needs.

Know how to guide and seat a visually impaired person.

Know how to guide and seat a visually impaired person.

Know when to treat an older person like anyone else, and when they require special communication techniques.

Know when to treat an older person like anyone else, and when they require special communication techniques.

Help people with speech impairments to express their needs and thoughts.

Help people with speech impairments to express their needs and thoughts.

Interacting Successfully

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access