Areas of focus

The target population of the I-PiCC pilot was high-risk, high-cost elderly individuals living in the community with multiple co-morbid conditions who would benefit from greater PCP integration and involvement. Focusing on aged patients in their homes allows a clinician to see the many challenges this population must overcome in order to maintain independence and successfully age in place.

Many factors contributed in choosing in-home visits to address care coordination and chronic disease education as opposed to an office-based or hospital-based model:

- “Geriatric syndromes” are best observed in a person’s home, not in the PCP’s office or in a hospital.

- Lifestyle impact on health becomes more apparent in the home environment (such as food choices, smoking, alcohol consumption, financial resources, and caregiving challenges).

- Over-the-counter medications that many people “forget” to tell their PCPs about are not necessarily harmless, and often contribute to polypharmacy challenges. They are also frequently omitted from a patient’s medication profile.

- Adults learn better when they are not at a point of transition/anxiety (hospital admission/discharge or in their PCP’s office) and when information is repeated many times, especially if it is unfamiliar.

- To assist our seniors and keep them on-track to successful aging, clinicians need to meet them “where they are most comfortable” and in control – in their homes.

Program-planning involved contributions from every team member. The following principles and considerations were integrated into program operations:

- Historically, the population we were targeting is generally considered to be made up of “passive participants” in the health care system.

- The intervention needed to be structured to ensure maximum engagement of the participants and motivate them to pursue lasting behavior change after the pilot was completed. Our strategy was to coach our patients so we coined the phrase “Cue, Don’t Do.” An interdisciplinary team was imperative to meet the wide variety of needs the target population had.

- Geriatrics is a specialty. Specific education and training in geriatrics prior to starting the project was an absolute necessity to ensure all team members had a minimal level of competency.

- The program focus was on coaching, engaging, and motivating our patients, not providing skilled hands-on care that could be provided by home health personnel.

- Care plans are passive so we decided to use a more “pro-active” tool to engage participants. The I-PiCC team opted to implement a Co-Plan. This tool was more patient-centered and identified interventions and actions that the patients could do to change their health, in addition to the contributions of team members.

- Transitions of care needed to be specifically addressed because they are particularly difficult for the geriatric patient (Coleman & Boult 2003).

- A non-clinical teammate was chosen to address non-clinical “care coordination” participant needs.

- The duration of the intervention would be four months (16 weeks). This time frame was similar to successful transition projects administered by Naylor and colleagues. This length of time was also determined to be the minimum amount of time necessary to observe behavior change (Naylor 1990).

- The model’s interventions needed to be easily replicated with specific measurable outcomes, as well as successful clinical outcomes, be cost effective, and demonstrate a return on investment.

- The model had to “wrap around” existing primary care practices to expand into their patient’s homes and perhaps offer solutions to the PCP crises.

Patient selection

Our target population was geriatric patients, 65 years of age and older, taking five or more medications a day with two or more co-morbid conditions, and with cognition that allowed them to be coached (or a caregiver willing to accept the coaching on behalf of the patients). In addition, they were identified by the practice manager as being a “high cost” managed care member. We looked to target those individuals who were seriously ill but not actively or imminently dying. A total of 78 individuals were identified by the physician practice management team in accordance with project guidelines; seven were screened who did not meet criteria, 31 declined to participate and four were identified as end stage and were referred to hospice. Forty individuals enrolled in the program; 32 completed the entire four month intervention, and eight completed at least two but not all four months due to death or subsequent placement in long term care.

Prior to entry all participants completed the SF-12 (V2), an instrument used to measure self-perception of health (Ware et al. 1996) in a face-to-face interview with project staff. The SF-12 measures eight domains of health and provides two scores, one for physical health and one for mental health (Ware et al. 1998). Based on a score in the 30-39 range, 90% of patients were identified as “moderately disabled,” indicating they were seriously ill but not terminal.

I-PiCC components

I-PiCC offered an interdisciplinary team that provided structured and scheduled in-home visits and ongoing telephonic support between regular PCP office visits. The program’s initial focus during the first month was to conduct a thorough nurse-driven geriatric assessment in order to aid in targeting potential areas of knowledge deficit or personal risk, and medication reconciliation and optimization by the pharmacist. The intervention then focused on the assessment results and participant’s specific health care needs.

The clinical team

A geriatric clinical nurse specialist (GCNS) lead the team and the project. The GCNS’s role was to oversee the project, ensure adhearance to operational guidelines, collect data, and provide initial plus ongoing education to other team members. No direct patient care was provided by the GCNS. The GCNS held weekly clinical reviews of each patient with team members. An RN was the patient’s health coach and ultimately responsible for the team’s interventions and action plans. As “Co-Plan” implementer, the RN provided on-going health coaching and plan reassessment. The RN assessed the patient’s readiness to learn, make change, and continue to monitor motivation for change throughout the project. The RN also conducted in-home visits once or twice a month per patient. In addition, the RN had numerous telephonic encounters driven by patient need to reinforce educational content and discuss potential risk factors for hospital readmission.

A pharmacist conducted an initial in-home assessment focusing on medication reconciliation and patient education. The reconciliation process was taken one step further by running potential drug interactions, screening for medications on the Beers lists, and offering recommendations for optimization of medications to the patient’s PCP. The pharmacist worked with each patient to develop a pillbox system to meet their needs and reduce errors in filling their pillboxes, assisted with specialty packaging from their pharmacy if indicated, and guided patients in the disposal of expired or unused medication. They made follow-up visits if there was ongoing knowledge deficit or whenever a participant was admitted to the hospital and returned home with medication changes. Additionally, a social worker assisted patients in overcoming behaviors that unfavorably impacted their health, and assisted with identification of community resources when needed.

When a patient required care coordination, we utilized a personal care coordinator (PCC) to address the patient’s care coordination needs. The PCC was a non-licensed support person who assisted the patients, their caregivers, and the clinical staff. They supplemented the clinical team by assisting with making follow-up appointments with physicians, leaving appointment reminders, and identifying community resources to support aging in place (e.g., homemakers, home repairs, transportation etc). The PCC filled a vital role that supported wellness, personal well being and an overall decrease in health care spending.

Acknowledging geriatrics as a specialty, a 16-hour orientation was developed that focused on common geriatric syndromes and chronic diseases, behavioral change theory, coaching, medication optimization and reconciliation, and orientation to home care/community care.

The patient Co-Plan

Care plans have been used by many disciplines within the health care system to prioritize goals of care and interventions. It is generally not given to the patient and the degree of patient input is highly variable, even within identical settings. Our purpose of modifying the traditional care plan was three-fold: (1) clinician’s negative perceptions of care plans – the team overwhelmingly felt that care plans were a significant amount of upfront work and did little to help the clinician or patient; (2) the change in wording made it “ok” for patients, caregivers, clinicians, and non-clinicians to contribute to the document; and (3) use of the term “Co-Plan” instead of care plan was decided so that it was clear to the participant that this was not a passive process and their actions would be required to meet the goals that they set.

The traditional care plan has three components: problems, interventions, and goals. The interventions section of a traditional care plan captures the clinical team’s actions. I-PiCC chose to make the interventions applicable to both clinicians and patients. The goals are usually health care team goals, not patient goals, so the clinicians were mindful that Co-Plan goals were the individual patients’.

In the health care system clinicians struggle with the patient’s “health care wants” and “health care needs”. Reconciling wants and needs is not an easy negotiation and clinicians, due to time constraints and numerous other factors, frequently default to addressing the patient’s “needs” by placing the most critical at the top of the list. If a patient does not share the team’s assessment of his/her needs, or feels that his/her “wants” are ignored, unwittingly this may create a situation that fosters an unengaged patient. Sometimes these individuals may be given the ominous title of “non-compliant.” In our model there could never be a non-compliant patient. The goals were determined by the patient in a marriage of wants and needs. The action items were set by the patient. The deliverables from the health care team were clearly stated so the patient knew what to expect “next”. Co-Plans were updated at every point of contact (phone or in person) by each team member, as well as by patient or caregiver request. When a Co-Plan was updated the patient was provided with a copy of the revisions within 24 hours.

Behavior change approach

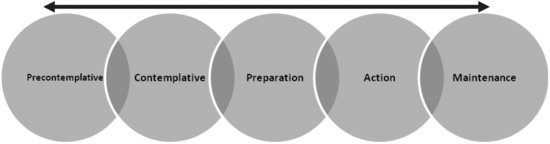

Our overall goal was to coach and empower the patients, positioning them with skills to better manage their health and future health care experiences. We acknowledged that this would require a significant behavior change for many patients. There are numerous theories that address behavioral change. We chose to use motivational interviewing and the Transtheoretical Model (TTM) of change. The TTM assesses an individual’s readiness to act on a new behavior and provides strategies to guide the individual through the stages of change to a point of action and sustainability (maintenance). A person can move forward in the process and continue to progress (to the right of the diagram) or regress (movement to the left; Prochaska & Velicer 1997; 1998).

Figure 27.2 The Transtheoretical Model of Change

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree