Instructional Materials

Diane Hainsworth

Kara Keyes

CHAPTER HIGHLIGHTS

General Principles

Choosing Instructional Materials

The Three Major Components of Instructional Materials

Delivery System

Content

Presentation

Types of Instructional Materials

Written Materials

Demonstration Materials

Audiovisual Materials

Evaluation Criteria for Selecting Materials

State of the Evidence

KEY TERMS

instructional materials

characteristics of the learner

characteristics of the media

characteristics of the task

delivery system

realia

illusionary representations

symbolic representations

replica

analogue

symbol

audiovisual materials

multimedia learning

blended learning

OBJECTIVES

After completing this chapter, the reader will be able to

Differentiate between instructional materials and instructional methods.

Identify the three major variables (learner, task, and media characteristics) to be considered when selecting, developing, and evaluating instructional materials.

Cite the three components of instructional materials required to communicate educational messages effectively.

Discuss general principles applicable to all types of media.

Identify the multitude of instructional materials—printed, demonstration, and audiovisual media—available for client and professional education.

Describe the general guidelines for development of printed materials.

Analyze the advantages and disadvantages specific to each type of instructional medium.

Evaluate the type of media suitable for use depending on such variables as the size of the audience, the resources available, and the characteristics of the learner.

Identify where educational tools can be found.

Critique instructional materials for value and appropriateness.

Recognize the supplemental nature of media’s role in client, staff, and student education.

Whereas instructional methods are the approaches used for teaching, instructional materials are the vehicles by which information is communicated. Often these terms are used interchangeably and are frequently referred to in combination with one another as teaching strategies and techniques. Nevertheless, instructional methods and instructional materials are not one and the same, and a clear distinction can and should be made between them. Instructional methods are the way information is taught. Instructional materials, which include printed, demonstration, and audiovisual media, are the adjuncts used to enhance teaching and learning. These multimedia approaches must be examined from a scientific, evidence-based perspective, grounded in theory on how people learn (Mayer, 2005).

Instructional materials, also known as tools and aids, are mechanisms or objects to transmit information that are intended to supplement, rather than replace, the act of teaching and the role of the teacher. These modes by which information is shared with the learner often are not considered in depth, yet instructional materials represent an important, complex component of the educational process. Given the numerous factors affecting both the teacher and the learner, such as the increase in staff workloads, the decrease in length of inpatient stays or outpatient visits, the increase in client acuity, the alternative settings in which education is now delivered, and the shrinking resources for educational services, it is imperative that the nurse educator understand the various types of printed, demonstration, and audiovisual media available to complement teaching efforts efficiently and effectively.

Instructional materials provide the nurse educator with tools to deliver education messages creatively, clearly, accurately, and in a timely fashion. They help the educator reinforce information,

clarify abstract concepts, and simplify complex messages. Multimedia resources serve to stimulate a learner’s senses as well as add variety, realism, and enjoyment to the teaching-learning experience. They have the potential to assist learners not only in acquiring knowledge and skills, but also in retaining more effectively what they learn. Research indicates that a variety of printed, demonstration, and audiovisual materials do, indeed, facilitate teaching and learning.

clarify abstract concepts, and simplify complex messages. Multimedia resources serve to stimulate a learner’s senses as well as add variety, realism, and enjoyment to the teaching-learning experience. They have the potential to assist learners not only in acquiring knowledge and skills, but also in retaining more effectively what they learn. Research indicates that a variety of printed, demonstration, and audiovisual materials do, indeed, facilitate teaching and learning.

This chapter provides a systematic overview of the process for selecting, developing, implementing, and evaluating instructional materials. Various types of audiovisual media are examined with an eye toward matching them to the particular characteristics of learners, the specific topics to be taught, and the variable situations and settings for teaching and learning. The advantages and disadvantages of each of the media types are discussed. Although the choice of instructional materials often depends on availability or cost, whichever tools are selected should enhance achievement of expected learning outcomes.

This chapter is intended to inform nurse educators about various media options so that they can make informed choices regarding appropriate instructional materials that fit the learner, that affect the motivation of the learner, and that accomplish the learning task. Whether nurses educate clients and their families, nursing staff, or nursing students, the same principles apply in making decisions about the type of materials selected for instruction.

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Before selecting or developing media from the multitude of available options, nurse educators should be aware of the following general principles regarding the effectiveness of instructional materials:

The teacher must be familiar with the media content before using a tool.

Printed, demonstration, and audiovisual materials can change learner behavior by influencing cognitive, affective, and psychomotor development.

No one tool is considered better than another in enhancing learning because the suitability of any particular medium depends on many variables.

The tools should complement the instructional methods.

The choice of media should be consistent with the subject content to be taught and match the tasks to be learned to assist the learner in accomplishing predetermined behavioral objectives.

The instructional materials should reinforce and supplement—not substitute for—the educator’s teaching efforts.

Media should match the available financial resources.

Instructional aids should be appropriate for the physical conditions of the learning environment, such as the size and seating of the audience, acoustics, space, lighting, and display hardware (delivery mechanisms) available.

Media should complement the sensory abilities, developmental stages, and educational level of the intended audience.

The messages imparted by instructional materials must be accurate, valid, authoritative, up-to-date, appropriate, unbiased, and free of any unintended content.

The media should contribute meaningfully to the learning situation by adding and diversifying information.

CHOOSING INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIALS

Nurse educators must consider many important variables when selecting instructional materials. The role of the nurse educator goes beyond the dispensing of information only; it also involves skill in designing and planning for instruction. Learning can be made more enjoyable for both the learner and the teacher if the educator knows which instructional materials are available, as well as how to choose and use them so as to best enhance the teaching-learning experience.

Knowledge of the diversity of instructional tools and their appropriate use enables the teacher to make education more interesting, challenging, and effective for all types of learners. With current trends in healthcare reform, educational strategies to teach clients, in particular, need to include instructional materials for health promotion and illness prevention, as well as instructional materials for health maintenance and restoration.

Making appropriate choices of instructional materials depends on a broad understanding of three major variables: (1) characteristics of the learner, (2) characteristics of the media, and (3) characteristics of the task to be achieved (Frantz, 1980). A useful mnemonic for remembering these variables is LMAT—standing for “learner, media, and task.”

1. Characteristics of the learner. Many variables are known to influence learning. Educators, therefore, must know their audience so that they can choose those media that will best suit the needs and abilities of various learners. They must consider sensorimotor abilities, physical attributes, reading skills, motivational levels (locus of control), developmental stages, learning styles, gender, socioeconomic characteristics, and cultural backgrounds.

2. Characteristics of the media. A wide variety of media—printed, demonstration, and audiovisual—are available to enhance methods of instruction for the achievement of objectives. Print materials are the most common form through which such information is communicated, but nonprint media include an expansive range of audio and visual possibilities. Because no single medium is more effective than all other options, the educator should be flexible in considering a multimedia approach to complement methods of instruction.

3. Characteristics of the task. Identifying the learning domain (cognitive, affective, and/or psychomotor) as well as the complexity of those behaviors that are required, which are based on the predetermined behavioral objectives, defines the task(s) to be accomplished.

THE THREE MAJOR COMPONENTS OF INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIALS

Depending on the instructional methods chosen to communicate information, educators must decide which media are potentially best suited to assist with the process of teaching and learning. The delivery system (Weston & Cranston, 1986), content, and presentation (Frantz, 1980) are the three major components of media that educators should keep in mind when selecting print and nonprint materials for instruction.

Delivery System

The delivery system includes both the software (the physical form of the materials) and the hardware used in presenting information. For instance,

the educator giving a lecture might choose to embellish the information being presented by using a delivery system, such as the combination of PowerPoint slides (software) and a computer (hardware). The content on DVDs (software), in conjunction with DVD players (hardware), and CD-ROM programs (software), in conjunction with computers (hardware), are other examples of delivery systems.

the educator giving a lecture might choose to embellish the information being presented by using a delivery system, such as the combination of PowerPoint slides (software) and a computer (hardware). The content on DVDs (software), in conjunction with DVD players (hardware), and CD-ROM programs (software), in conjunction with computers (hardware), are other examples of delivery systems.

The choice of the delivery system is influenced by the size of the intended audience, the pacing and flexibility needed for delivery, and the sensory aspects most suitable to the audience. More recently, the geographical distribution of the audience has emerged as a significant influence on choice of delivery systems, given the popularity of distance education modalities.

Content

The content (intended message) is independent of the delivery system and is the actual information being communicated to the learner, which might focus on any topic relevant to the teachinglearning experience. When selecting media, the nurse educator must consider several factors:

The accuracy of the information being conveyed. Is it up-to-date, reliable, and authentic?

The appropriateness of the medium to convey particular information. Brochures or pamphlets and podcasts, for example, can be very useful tools for sharing information to change behavior in the cognitive or affective domain but are not ideal for skill development in the psychomotor domain. Videos, as well as real equipment with which to perform demonstrations and return demonstrations, are much more effective tools for conveying information relative to learning psychomotor behaviors.

The appropriateness of the readability level of materials for the intended audience. Is the content written at a literacy level suitable for the learner’s reading and comprehension abilities? The more complex the task, the more important it is to write clear, simple, succinct instructions enhanced with illustrations so that the learner can understand the content.

Presentation

According to Weston and Cranston (1986), the form of the message—in other words, how information is presented—is the most important component for selecting or developing instructional materials. However, a consideration of this aspect of the media is frequently ignored. Weston and Cranston describe the form of the message as occurring along a continuum from concrete (real objects) to abstract (symbols).

REALIA

Realia refers to the most concrete form of stimuli that can be used to deliver information. For instance, an actual woman demonstrating breast self-examination is the most concrete example of realia. Because this form of presentation might be less acceptable for a wide range of teaching situations, the next best choice would be a manikin. Such a model, which is analogous to a human figure, has many characteristics that simulate reality, including size and three-dimensionality (width, breadth, and depth), but without being the true figure that may very well cause embarrassment for the learner. The message is less concrete, yet using an imitation of a person as an instructional medium allows for an accurate presentation of information with near-maximal stimulation of the learners’ perceptual abilities. Further along the continuum of realia is a video presentation of a woman performing breast self-examination. The learner could still learn

accurate breast self-examination by viewing such a video, but the aspect of three dimensionality is absent. In turn, the message becomes less concrete and more abstract.

accurate breast self-examination by viewing such a video, but the aspect of three dimensionality is absent. In turn, the message becomes less concrete and more abstract.

ILLUSIONARY REPRESENTATIONS

The term illusionary representations applies to a less concrete, more abstract form of stimuli through which to deliver a message, such as moving or still photographs, audiotapes projecting true sounds, and real-life drawings. Although many realistic cues, including dimensionality, are missing from this category of instructional materials, illusionary media have the advantage of offering learners a variety of real-life visual and auditory experiences to which they might otherwise not have access or exposure because of such factors as location or expense. For example, pictures that show how to stage decubitus ulcers and audiotapes that help learners discriminate between normal and abnormal lung sounds, although more abstract in form, do to some degree resemble or simulate realia.

SYMBOLIC REPRESENTATIONS

The term symbolic representations applies to the most abstract types of messages, though they are the most common form of stimuli used for instruction. These types of representations include numbers and letters of the alphabet, symbols that are written and spoken as words that are employed to convey ideas or represent objects. Audiotapes of someone speaking, live oral presentations, graphs, written texts, handouts, posters, flipcharts, and whiteboards on which to display words and images are vehicles to deliver messages in symbolic form. The chief disadvantage of symbolic representations stems from their lack of concreteness. The more abstract and sophisticated the message, the more difficult it is to decipher and comprehend. Consequently, symbolic representations may be inappropriate as instructional materials for very young children, learners from different cultures, learners with significant literacy problems, and individuals with cognitive and sensory impairments.

When making decisions about which tools to select to best accomplish teaching and learning objectives, the nurse educator should carefully consider these three media components. When choosing from a wide range of print and audiovisual options, key issues to be taken into account include the various delivery systems available, the content or message to be conveyed, and the form in which information will be presented. Educators must remember that no single medium is suitable for all audiences in promoting acquisition and retention of information. Most important, the function of instructional materials must be understood—that is, to supplement, complement, and support the educator’s teaching efforts for the successful achievement of learner outcomes.

TYPES OF INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIALS

Written Materials

Handouts, leaflets, books, pamphlets, brochures, and instruction sheets (all symbolic representations) are the most widely employed and most accessible type of media used for teaching. Printed materials have been described as “frozen language” (Redman, 2007, p. 34) and are the most common form of teaching tool because of the distinct advantages they provide to enhance teaching and learning.

The greatest virtues of written materials are as follows:

They are available to the learner as a reference for reinforcement of information when the nurse is not immediately present to answer questions or clarify information.

They are widely used at all levels of society, so this medium is acceptable and familiar to the public.

They are easily obtainable through commercial sources, usually at relatively low cost and on a wide variety of subjects, for distribution by educators.

They are provided in convenient forms, such as pamphlets, which are portable, reusable, and do not require software or hardware resources for access.

They are becoming more widely available in languages other than English as a result of the recognition of significant cultural and ethnic shifts in the general population.

They are suitable to a large number of learners who prefer reading as opposed to receiving messages in other formats.

They are flexible in that the information is absorbed at a speed controlled by the reader.

The disadvantages of printed materials include the following facts:

Written words are the most abstract form in which to convey information.

Immediate feedback on the information presented may be limited.

A large percentage of materials are written at too high a level for reading and comprehension by the majority of clients (Doak, Doak, Friedell, & Meade, 1998).

Written materials are inappropriate for persons with visual or cognitive impairment.

COMMERCIALLY PREPARED MATERIALS

A wealth of brochures, posters, pamphlets, and client-focused texts is currently available from commercial vendors. Whether such materials enhance the quality of learning is an important question for nurse educators to consider when trying to evaluate these products for content, readability, and presentation. Commercial products may or may not be produced in collaboration with health professionals, which raises the question of how factual the information may be. For example, materials prepared by pharmaceutical companies or medical supply companies might not be free of bias. Educators must ask several questions when reviewing printed materials that have been prepared commercially, including the following:

Who produced the item? Evidence should make it clear whether input was provided by a nurse or other healthcare professional with expertise in the subject matter.

Can the item be previewed? The educator should have an opportunity to examine the accuracy and appropriateness of content to ensure that the information needed by the target audience is provided.

Is the price of the teaching tool consistent with its educational value? Getting across an important message effectively may justify a significant cost outlay, especially if the tool can be used with large numbers of learners. However, simple printed instruction sheets may do the job just as well at less expense and can provide the educator with the ability to update the information on a more frequent basis.

The main advantage of using commercial materials is that they are readily available and can be obtained in bulk for free or at a relatively low cost (Fraze, Griffith, Green, & McElroy, 2010). A nurse educator might need to spend hours researching, writing, and copying materials to create informational materials of equal quality and value, so commercially available materials can save valuable time. Also, some commercial materials are available online that can be customized to individual clients.

The disadvantages of using commercial materials include issues of cost, accuracy and adequacy

of content, and readability of the materials. Some educational booklets are expensive to purchase and impractical to give away in large quantities to learners unless the educator uses materials that can be individualized. Fraze and associates (2010) have developed a checklist to help healthcare providers determine the appropriateness of printed education materials for use by their clients for improvement of health outcomes in various clinical settings.

of content, and readability of the materials. Some educational booklets are expensive to purchase and impractical to give away in large quantities to learners unless the educator uses materials that can be individualized. Fraze and associates (2010) have developed a checklist to help healthcare providers determine the appropriateness of printed education materials for use by their clients for improvement of health outcomes in various clinical settings.

INSTRUCTOR-COMPOSED MATERIALS

Nurse educators may choose to write their own instructional materials so as to realize cost savings or to tailor content to specific audiences. Composing materials offers many advantages (Brownson, 1998; Doak et al., 1998). For example, by writing their own materials, educators can tailor the information to accomplish the following points:

Fit the institution’s policies, procedures, and equipment

Build in answers to those questions asked most frequently by clients

Highlight points considered especially important by the team of physicians, nurses, and other health professionals

Reinforce specific oral instructions that clarify difficult concepts

Doak and colleagues (1998) outline specific suggestions for tailoring information to help clients want to read and remember the message and to act on it. These authors define “tailoring” as personalizing the message so that the content, structure, and image fit an individual client’s learning needs. To accomplish this goal, they suggest techniques such as writing the client’s name on the cover of a pamphlet, and opening a pamphlet with a client and highlighting the most important information as it is verbally reviewed. In another example, Feldman (2004) describes successful use of childcare checklists that had simple line drawings (no more than two to a page) coupled with brief written descriptions that led parents in stepby-step fashion through specific care tasks, such as bathing a baby. Audiotapes also accompanied these pictures and simple instructions. Additional studies support the efficacy of tailored instruction over nontailored messages in achieving reading, recall, and follow-through in health teaching (Campbell et al., 1994; Skinner, Strecher, & Hospers, 1994).

Of course, composing materials also has disadvantages. Educators need to exercise extra care to ensure that materials are well written and laid out effectively, which can be a time-consuming endeavor. Although nurse educators are expected to enhance their methods of teaching with instructional materials, few have ever had formal training in the development and application of written materials. Many tools written by nurses are too long, too detailed, and composed at too high a level for the target audience. Doak, Doak, and Root (1996) and Brownson (1998) suggest the following guidelines to ensure the clarity of self-composed printed education materials:

Make sure the content is accurate and up-to-date.

Organize the content in a logical, stepby-step, simple fashion so that learners are being informed adequately but are not overwhelmed with large amounts of information. Avoid giving detailed rationales because they may unnecessarily lengthen the written information. Prioritize the content to address only what learners need to know. Content that is nice to know can be addressed orally on an individual basis.

Make sure the information succinctly discusses the what, how, and when. Follow the KISS rule: Keep it simple and smart. This can best be accomplished by putting the information into a

question-and-answer format or by dividing the information into subheadings according to the nature of the content.

Regardless of the format employed, avoid medical jargon whenever possible, and define any technical terms in laypeople’s language. Sometimes it is important to expose clients to technical terms because of complicated procedures and ongoing interaction with the medical team, so careful definitions can minimize misunderstandings. Be consistent with the words used.

Find out the average grade in school completed by the targeted client population, and write the client education materials two to four grade levels below that level. For individuals who are nonliterate, pictographs can increase recall of spoken medical instruction (Houts et al., 1998; Kessels, 2003).

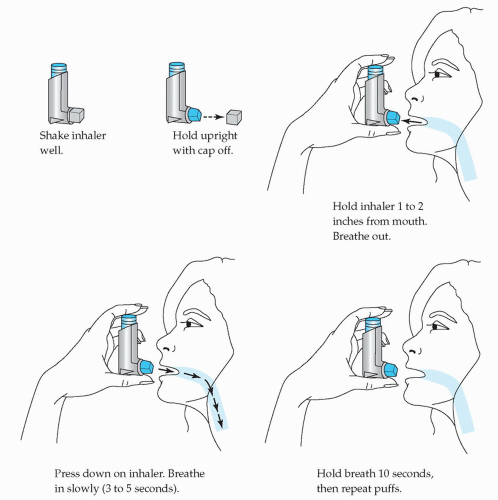

Always state things in positive—not negative—terms. Never illustrate incorrect messages. For example, depicting a hand holding a metereddose inhaler in the mouth not only incorrectly illustrates a drug delivery technique (Weixler, 1994) but also reinforces that message through the image’s visual impact alone. Figure 12-1 illustrates the correct way to use an inhaler and reinforces a positive message.

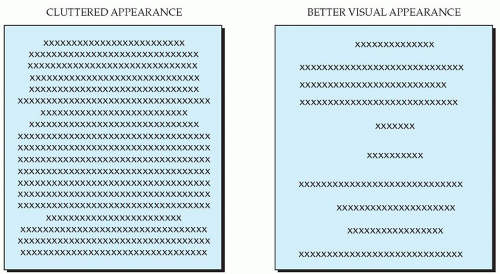

In addition to the guidelines for clarity and completeness in constructing written materials, format and appearance are equally important in motivating learners to read the printed word. If the format and appearance are too detailed, learners will feel overwhelmed; in such a case, instead of attracting the learners, you will discourage and repel them (Figure 12-2).

EVALUATING PRINTED MATERIALS

When evaluating printed materials, educators should keep in mind the following considerations. Nature of the Audience What is the average age of the audience? For instance, older adults tend to prefer printed materials that they can read at their leisure. Lengthy materials may be less problematic for older learners, who frequently have enough time and patience for reading educational materials. Children or clients who have low literacy skills, however, like short printed materials with many illustrations.

Also, what is the preferred learning style of the particular audience? Printed materials with few illustrations are poorly suited to clients who not only have difficulty reading but also do not like to read. Representations of information in the form of simple pictures, graphs, and charts can be included with the content of printed materials for those individuals who are visual and conceptual learners.

In addition, does the audience have any sensory deficits? Vision deficits are common among older adult clients, and deficits in short-term memory may pose a problem for comprehension. Having materials that can be reread at the learner’s own convenience and pace can reinforce earlier learning and minimize confusion over treatment instructions. To accommodate those individuals with vision impairments, use a large typeface and lots of white space, separate one section from another with ample spacing, highlight important points, and use black print on white paper.

Literacy Level Required The effectiveness of client education materials for helping the learner accomplish behavioral objectives can be totally undermined if the materials are written at a level beyond the comprehension of the learner. The Joint Commission (formerly known as the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations) mandates that health information be presented in a manner that can be understood by clients and family members. This requirement

underscores the importance of screening potential educational tools to be used as adjuncts to various teaching methods. A number of formulas (e.g., Fog, SMOG, Fry) are available for determining readability.

underscores the importance of screening potential educational tools to be used as adjuncts to various teaching methods. A number of formulas (e.g., Fog, SMOG, Fry) are available for determining readability.

Linguistic Variety Available Linguistic variety refers to choices of printed materials in different languages. These options may be limited because duplicate materials in more than one language are costly to publish and not likely to be undertaken

unless the publisher anticipates a large demand. The growth of minority populations in the United States has promoted increasing attention to the need for non-English language teaching materials. Regional differences exist, such that there may be greater availability of Asian-language materials on the West Coast and more Spanish-language materials in the Southwest and Northeast than in other parts of the United States.

unless the publisher anticipates a large demand. The growth of minority populations in the United States has promoted increasing attention to the need for non-English language teaching materials. Regional differences exist, such that there may be greater availability of Asian-language materials on the West Coast and more Spanish-language materials in the Southwest and Northeast than in other parts of the United States.

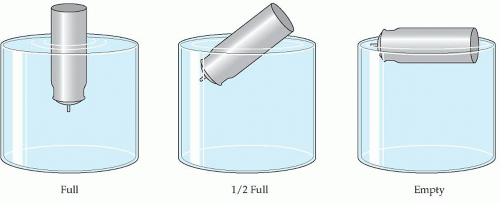

Brevity and Clarity In education, as in art, simpler is better. Remind yourself of the KISS rule: Keep it simple and smart. Address the critical facts only. What does the client need to know? Choose words that explain how; the why can be filled in by a lecture, one-to-one instruction, or group discussion. Include simple pictures that illustrate step by step the written instructions being given. Figure 12-3 provides a good example of a clear, easy-to-follow instructional tool that is used to teach a patient with asthma how to determine when a metered-dose inhaler is empty. Using simple graphics and minimal words, it guides the learner through the procedure with very little room for misinterpretation and is suitable for a wide range of audiences.

Layout and Appearance The appearance of written materials is crucial in attracting learners’ attention and getting them to read the information. If a tool has too much wording, with inadequate spacing between sentences and paragraphs, small margins, and numerous pages, the learner may find it much too difficult and too time consuming to read (see Figure 12-2).

Doak and colleagues (1996) point out that allowing plenty of white space is the most important step that educators can take to improve the

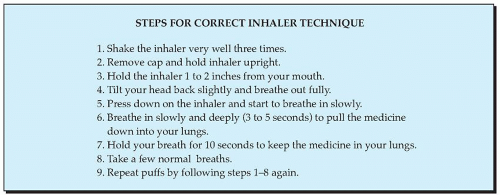

appearance of written materials. This means double spacing, leaving generous margins, indenting important points, using bold characters, and separating key statements with extra space. Inserting a graphic in the middle of the text can break up the print and may be visually appealing, as well as provide a mechanism for reinforcing the narrative information. Redman (2007) states that pictorial learning is better than verbal learning for recognition and recall. For topics that lend themselves to concrete explanations, this is especially true. An example used earlier in this chapter is teaching the psychomotor task of using a metered-dose inhaler (see Figure 12-1). Figure 12-4 includes simple step-by-step instructions written in the active voice on the correct inhaler technique to use.

appearance of written materials. This means double spacing, leaving generous margins, indenting important points, using bold characters, and separating key statements with extra space. Inserting a graphic in the middle of the text can break up the print and may be visually appealing, as well as provide a mechanism for reinforcing the narrative information. Redman (2007) states that pictorial learning is better than verbal learning for recognition and recall. For topics that lend themselves to concrete explanations, this is especially true. An example used earlier in this chapter is teaching the psychomotor task of using a metered-dose inhaler (see Figure 12-1). Figure 12-4 includes simple step-by-step instructions written in the active voice on the correct inhaler technique to use.

Opportunity for Repetition Written materials can be read later, and again and again, by the learner to reinforce the teaching when the educator is not there to answer questions. Thus it is an advantage if materials are laid out in a simple question-andanswer format. Questions demand answers, and this format allows clients to find information easily for repeated reinforcement of important messages. If educators write their own materials, they also must be mindful of the need to keep information current and to update it for changing client populations.

Concreteness and Familiarity Using the active voice is more immediate, directive, and concrete. For example, “Shake the inhaler very well three times” is more effective than “The inhaler should be shaken thoroughly” (see Figure 12-4). Also, the importance of using plain language instead of medical jargon cannot be overemphasized. Inadequate client understanding of common medical terms used by healthcare providers is a significant factor in noncompliance with medical regimens. A number of studies indicate that clients understand medical terms at a much lower rate than nurses expect (Estey, Musseau, & Keehn, 1994; Lerner, Jehle, Janicke, & Moscati, 2000).

In summary, instructor-designed or commercially produced printed instructional materials are widely used for a broad range of audiences. They vary in literacy demand levels and may be found written in several languages. Table 12-1 summarizes their basic advantages and disadvantages.

TABLE 12-1 Basic Advantages and Disadvantages of Printed Materials | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Demonstration Materials

Demonstration materials include many types of visual, hands-on nonprint media, such as models and real equipment, as well as a hybrid of printed words and visual illustrations (diagrams, graphs, charts, photographs, and drawings) depicted on what are known as displays, such as posters, bulletin boards, flannel boards, flip charts, chalkboards, and whiteboards. These types of media represent unique ways of communicating messages to the learner. Demonstration materials primarily stimulate the visual senses but can combine the sense of sight with touch and sometimes even smell and taste. From these various forms of demonstration materials, the educator can choose one or more to complement teaching efforts in reaching predetermined objectives. Just as with written tools, these aids must

be accurate and appropriate for the intended audience. Ideally, these media forms will bring the learner closer to reality and actively engage him or her in a visual and participatory manner. As such, demonstration tools are useful for cognitive, affective, and psychomotor skill development. The major forms of demonstration materials—models and displays—are discussed in detail here.

be accurate and appropriate for the intended audience. Ideally, these media forms will bring the learner closer to reality and actively engage him or her in a visual and participatory manner. As such, demonstration tools are useful for cognitive, affective, and psychomotor skill development. The major forms of demonstration materials—models and displays—are discussed in detail here.

MODELS

Models are three-dimensional instructional tools that allow the learner to immediately apply knowledge and psychomotor skills by observing, examining, manipulating, handling, assembling, and disassembling objects while the teacher provides feedback (Rankin & Stallings, 2005). In addition, these demonstration aids encourage learners to think abstractly and give them the opportunity to use many of their senses (Boyd, Gleit, Graham, & Whitman, 1998). Whenever possible, the use of real objects and actual equipment is preferred—but a model is the next best thing when the real object is not available, accessible, or feasible, or is too complex to use. Because approximately 30% to 42% of people are visual learners and 20% to 25% are kinesthetic (hands-on) learners, using models not only capitalizes on their learning styles (preference for learning) but also enhances their retention and understanding of new information (Aldridge, 2009).

Three specific types of models are used for teaching and learning, as differentiated by Babcock and Miller (1994):

Replicas, associated with the word resemble

Analogues, associated with the words act like

Symbols, associated with the words stands for

A replica is a facsimile constructed to scale that resembles the features or substance of the original object. The dimensions of the reproduction may be decreased or enlarged in size to make demonstration easier and more understandable. A replica of the DNA helix is an excellent example of a model used to teach the complex concept of genetics. Replicas can be examined and manipulated by the learner to get an idea of how something looks and works. They are excellent choices for teaching psychomotor skills because they give the learner an opportunity for active participation through hands-on experience. Not only can the learner assemble and disassemble parts to see how they fit and operate, but the learner can also control the pace of learning.

Replicas are used frequently by the nurse educator when teaching anatomy and physiology. Models of the brain, limbs, heart, kidney, ear, eye, joints, and pelvic organs, for example, allow the learner to get a perspective on parts of the body not readily viewed without these teaching aids. Resuscitation dolls are a popular type of replica used to teach the skills of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). Learners who regularly refresh their skills using demonstration models as instructional tools are more likely to maintain regular and effective knowledge of use of the technique than are learners who do not (Pinto, 1993).

Using inanimate objects first is a technique educators can use to desensitize learners before doing invasive procedures on themselves or other human beings. Instructional models have been found to be effective in reducing fear and enhancing acceptance of certain procedures (Cobussen-Boekhorst, Van Der Weide, Feitz, & DeGier, 2000). For example, teaching a client with diabetes how to draw up and inject insulin can best be accomplished by using a combination of real equipment and replicas. Clients first draw up sterile saline in real syringes, practice injecting oranges, and then progress to a model of a person before actually injecting themselves. Sometimes, preliminary use of a video before starting to handle equipment

directly may be helpful if learners are very anxious about performing various procedures. For lessons aimed at psychomotor learning, educators can use skills checklists as a mechanism for evaluating the accuracy of return demonstrations. Simulation laboratories, for example, often use this evaluation method.

directly may be helpful if learners are very anxious about performing various procedures. For lessons aimed at psychomotor learning, educators can use skills checklists as a mechanism for evaluating the accuracy of return demonstrations. Simulation laboratories, for example, often use this evaluation method.

The second type of model is known as an analogue because it has the same properties and performs like the real object. Unlike replicas, analogue models are effective in explaining and representing dynamic systems. A computer model depicting how the human brain functions is one popular analogue. Although costly, a sophisticated human patient simulator is another analogue. The patient simulator is a manikin that physiologically responds to treatment in a manner similar to what would occur in live clients. Webbased patient simulation programs for teaching clinical reasoning to health professionals, such as physical therapists, is growing in popularity, and the feasibility of these computer analogues is being investigated (Huhn, Anderson, & Deutsch, 2008).

The third type of model is a symbol, which is used frequently in teaching situations. Written words, mathematical signs and formulas, diagrams, cartoons, printed handouts, and traffic signs are all examples of symbolic models that convey a message to the receiver through imaging, convention, or association. International signs, for example, convey a familiar and understandable message to individuals of multilingual or multicultural backgrounds. However, abbreviations and acronyms common to healthcare personnel, such as NPO, PRN, and PO, should be avoided when interacting with consumers because they are likely to be unfamiliar with these abbreviations.

The advantage of models is that they can adequately replace the real object, which may be too small, too large, too expensive, too complex, unavailable, or inappropriate for use in a teaching-learning situation. A vast array of models can be purchased from commercial vendors at varying prices (some for free) or improvised by the teacher. Models do not need to be expensive or elaborate to get concepts and ideas across (Aldridge, 2009; Rankin & Stallings, 2005). In particular, models enhance learning in the following ways:

Allow learners to practice acquiring new skills without being afraid of compromising themselves or others

Stimulate active learner involvement

Provide the opportunity for immediate testing of psychomotor and cognitive behaviors

Allow learners to receive instant feedback from the instructor

Appeal to the kinesthetic learner who prefers the hands-on approach to learning

In terms of their disadvantages, some models may not be suitable for the learner with poor abstraction abilities or for audiences with visual impairments, unless each individual is given the chance to tangibly appraise the object using other senses. Also, some models can be fragile, very expensive, bulky to store, and difficult to transport. Unless models are very large, they cannot be observed and manipulated by more than a few learners at any one time. However, this drawback can be overcome by using team teaching and by creating different stations at which to arrange replicas for demonstration purposes (Babcock & Miller, 1994).

DISPLAYS

Whiteboards, posters, story boards, flip charts, and bulletin boards are examples of displays found in most educational settings. In addition, the SMART Board is a large whiteboard that uses touch technology for detecting user input; it is similar in that respect to devices that use personal computing input, such as a mouse or keyboard (SMART, 2009). SMART Boards are growing in popularity but are still costly to purchase.

Displays are two-dimensional objects that serve as useful tools for a variety of teaching purposes. They can be used to convey simple or quick messages and to clarify, reinforce, or summarize information on important topics and themes. Although they have been referred to as static instructional tools owing to the fact that they are often stationary (Haggard, 1989), some displays may be portable and most are alterable. As demonstration materials, these tools can effectively achieve behavioral objectives by vividly representing the essence of relationships between subjects or objects. Whiteboards, flip charts, and SMART Boards are particularly versatile means of delivering information. Storyboards—visual tools that use pictures and written text to explain a sequence of events—are effective in providing consistent messages to clients in a simple, easy-to-understand format (Lowenstein, Foord, & Romano, 2009).

These board devices are most useful in formal classes, in group discussions, or during brainstorming sessions to spontaneously make drawings or diagrams (with contrasting colored chalk or markers) or to jot down ideas generated from participants while the educator is in the process of teaching. Information can be added, corrected, or deleted quickly and easily while the learners are actively following what the teacher is doing or saying. Such tools are excellent means of promoting participation, keeping the learners’ attention on the topic at hand, and noting and reinforcing the contributions of others. Flexible and handy, they provide opportunities for the teacher, in an immediate and direct fashion, to organize data, integrate ideas, perform on-the-spot problem solving, and compare and contrast various points of view. Also, unlike some other types of visuals, these display tools can allow learners to see parts of a whole picture while assisting the teacher in filling in the gaps.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access