6.1 Introduction

In this chapter we are delighted to include contributions written by nurses from a wide cross-section of nursing specialties. Each section introduces you to the particular learning opportunities and challenges inherent in these diverse clinical areas. While it has not been possible to cover every clinical specialty (there are just too many to explore), we are sure that the selection here provides insight into the wonderful opportunities available to nursing students. We are confident that you’ll be both inspired as these nurses share with you their passion for their work and motivated as they explain the unique qualities of different practice areas.

This chapter is designed to allow you to prepare for and plan your clinical placements. However, you’ll also be able to use it to delve into the different career pathways and specialities that are open to graduates. We hope that you find reading this chapter interesting and thought-provoking.

6.2 Aviation nursing

Fiona McDermid

RN, RM, MN, PhD Candidate

Lecturer, University of Western Sydney

Amanda Ferguson

RN, RM

Flight Nurse, Royal Flying Doctor Service, Queensland

6.2.1 An overview of aviation nursing

Welcome to the exciting world of Air Ambulance and the Royal Flying Doctor Service (RFDS). Aviation nursing involves the preparation, stabilisation and transport of patients within an aeromedical environment. This position involves flying in small aircraft to areas all over Australia, with a nurse and, of course, a pilot. Much of the work is routine, which includes transferring patients to and from major hospitals for care. The other aspect of this role is retrieval work, which involves flying with a doctor to transfer acutely unwell or injured patients to the appropriate facilities.

Aviation nurses are highly skilled professionals with extensive experience in critical care areas and midwifery. They practice autonomously and make independent decisions about patient care. In addition, they also play an important role as a flight crew member and are responsible for the safety of all those on board. Safety is the most important aspect of aviation nursing. Aviation nurses are trained extensively on safety procedures in and around aircrafts and compliance with safety procedures and policies is enforced with the full power of Federal law.

6.2.2 Learning opportunities

Aviation nursing is an unpredictable, but challenging area in which to work. It involves the use of completely different skills to those used in other fields of nursing and allows you to visit a multitude of places and health services. It is a wonderful experience that will broaden your view on the world of nursing and patient care.

Aviation nursing involves travel to rural and remote communities where health services are highly valued. You may meet and treat people of different cultures and therefore you should be appreciative of local customs and traditions, open minded and flexible in your approach.

As a visitor to the aviation environment you must understand and comply with safety procedures and regulations, for your own and for others’ protection. It is essential that you act in accordance with the instructions given to you by the senior nurse. The process of loading and off-loading of patients is complicated and potentially hazardous if not done correctly. It is essential that you listen and fully understand the correct operational procedures and manual handling procedure before attempting these activities, and do not attempt to undertake them by yourself.

6.2.3 Preparation for the placement

A basic understanding of aviation physiology prior to flying is important, as the environment is heavily influenced by the physiological phenomena of altitude, confined space and the extremes of weather and terrain. Within the aviation environment, these factors may impact on the transportation of patients and those on board. The physical environment often dehydrates individuals, which can result in a fatigue often referred to as jet-lag. The shifts can be long, particularly with retrieval work where times are only roughly estimated. To counteract these effects, it is strongly advised that you are well rested prior to flying and drink adequate amounts of fluids. The use of alcohol is prohibited for 24 hours prior to a flight.

As a visitor to any area, it is essential that you are appropriately attired and that you conduct yourself as a professional at all times. Punctuality is of major importance in flight nursing, because of the preparation of flight plans and take-off times. Flexibility, a positive attitude and a willingness to learn are also essential.

Space is limited on medical aircraft and weight is restricted. Medical equipment and supplies will always take precedence over general luggage. Remember, less is always best. Travel with a minimal amount of necessary items—often just a small bag is enough. It is also vital that no dangerous goods are carried on board. These items include cigarette lighters, matches, aerosol cans and other flammable items.

6.2.4 Challenges students may encounter

As space is restricted on flights, there may be occasions where you may be offloaded from a flight and unable to fly. This is referred to as being ‘bumped’, and is simply a matter of weight and space limitations.

Further reading

Articles in the Australian Journal of Rural Health.

Some historical further reading

Jarvis CM. Aviation nursing in Western Australian Kimberley. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 1995;3(2):68-71.

Stevens SY. Aviation pioneers: World War II air evacuation nurses. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 1994;26(2):95-100.

6.3 Community health nursing

Cheryle Morley

RN, RM, ICU Cert, CFHN Cert, Grad Cert Clinical Management, Master of Nursing (Clinical Leadership), IBCLC

Program Nurse Manager, Child and Family Health, Primary Care and Community Health Network, Sydney West Area Health Service

Bronwyn Warne

RN, BHSc (Nursing), Oncology Cert, Grad Cert Workplace Relations, Grad Cert Gerontology, Master of Nursing (Clinical Leadership)

Program Nurse Manager, Complex, Aged and Chronic Care, Primary Care and Community Health Network, Sydney West Area Health Service

6.3.1 Overview of community health nursing

Community nursing is a specialised clinical practice area in which nurses are involved in the provision of healthcare to community-based clients outside the acute hospital facilities. Services may be provided in the clients’ homes, clinics, neighbourhood centres and schools/preschools. Usually, nurses are based in community health centres and are part of a larger multidisciplinary team that covers a specific geographical area.

Historically, community nursing has been practised in many forms. The ‘good wives’ and ‘witches’ of the middle ages were perhaps early forms of community nurses, while in Australia the ‘brown nurses’, or Sisters of Charity, an order of nuns, established a visiting service to the poor and needy in 1838. A domiciliary nursing service began in Victoria in 1885, and in 1910 Lady Douglas, the wife of the then governor general, established the Bush Nursing Service (Burchill 1992, cited by Ward 1999).

The 1930s saw the introduction of baby-health sisters and school nurses to effect change on the high rate of infant mortality and poor health of school children. This specialisation continued until the 1970s, when the generalist model of community nursing, often referred to as ‘womb to tomb’ or ‘birth to death’, was conceived as a service in 1972. The aim of this service was to provide healthcare that focused on health promotion, prevention of illness, school health screening, home nursing, early childhood health services and supportive services for clients at risk of health breakdown (O’Connor 1973, cited by Ward 1999).

Following the acceptance and signing of the Alma Ata declaration by the Australian Government in Ottawa in 1978, and the consequent move by nurses to work within the framework of primary healthcare (PHC), the role, profile and range of skills required to practice as a community nurse have changed significantly in recent years (Ward 1999). The emphasis on early identification and intervention in child and family health, the ageing population and increasing number of people with a chronic illness have resulted in the need to change from a generalist nursing role to a specialist role (Kemp et al. 2005).

6.3.2 Learning opportunities

Placement in the community setting gives you a unique opportunity to observe and participate in nursing services provided for clients in their own environment, either at home, in clinics or in schools/preschools. In some communities the nurse works with clients across the lifespan, for example remote-area nursing, while in other communities the nurse will work in a team, focusing on a particular population group, such as the aged, those with a chronic illness, or children and families.

The model of care is client-focused, with a holistic approach to assessment and intervention, underpinned by partnerships and a strengths-based approach to child and family health, and supporting self-management in chronic care. These practice principles are directed by State and National policy, legislative requirements and clinical practice frameworks.

It is expected that you will work with a registered or enrolled nurse for the duration of the clinical placement. During the placement you will have the opportunity to be involved in some hands-on work; however, the specialised nature of the community nursing role may limit this aspect and could result in the clinical placement having a greater observational component for students than you might experience in other clinical settings.

There will be opportunities for you to explore one or many clinical specialty areas. These include child-and family-health nursing, such as home visits for families with newborn babies, audiometry, infant feeding and lactation, preschool vision screening and parenting groups. In complex, aged and chronic care you may visit clients who require chronic illness management, wound care, palliative care and continence management. There is also the opportunity to work with a number of allied health professionals who make up the larger multidisciplinary teams that provide services in community health.

You will benefit from discussion with health professionals in relation to the application of PHC principles, recognising the alteration in balance of power when working with clients in their own environment, and identifying networks and partnerships with other organisations and agencies that are core components of community health services (Centre for Health Equity Training, Research and Evaluation (CHETRE) 2005).

6.3.3 Preparing for the placement

For the placement to have the greatest value, you need to have a good knowledge and understanding of the core principles of nursing practice. These include codes of conduct, ethics and accountability, legal aspects of care (including consent for service), advocacy, infection control, documentation and confidentiality (client and staff). It is important that you recognise that these principles remain constant in all aspects of nursing practice, even though the work environment changes. Safety, security and manual handling have significant relevance in the community setting.

You need to discuss with your course/unit coordinator how your placement will be confirmed. In some situations the university undertakes all liaison, at other times you may need to contact the nurse unit manager (NUM) yourself before you begin the placement. You need to discuss the requirements for your placement in relation to dress code, identification and any supporting paperwork that you must present. In most instances a student-orientation package will be available on commencement, which provides you with an overview of the service.

Generally, you will leave the community health centre or base in the morning and not return until later in the afternoon. As you will be away from the centre for most of the day, bring fluids to drink and make enquiries about the availability of food if you cannot bring it from home.

6.3.4 Challenges students may encounter

Students have sometimes been challenged by the vast differences between community nursing and nursing in the acute setting (hospitals). Community nursing can seem isolated and less exciting, and the time spent with one client once per week is hard to equate with the hospitalised client who receives constant contact over a whole shift. Another challenge relates to the perception of nurses having ‘a lovely job just visiting new babies every day’, especially when you may be confronted with the psychosocial risks and vulnerabilities that impact on some of the families community nurses work with. The shift in emphasis from hospital to community care because of increased cost of hospitalisation, decreased length of stay (LOS) and early discharge means that nurses who practise in the community have to manage more highly dependent and complex clients than they have done in the past (Kemp et al. 2005). When nurses return to their base, paperwork is done and phone consultations and operational meetings take place. You will be encouraged to participate as you are able, but this period at the base also provides an opportunity to find out more about the clinical practice area, to observe other aspects of the service, such as intake of referrals, and to discuss services with other members of the multidisciplinary team.

Working with clients in their own environments means we need to accept that the client has the right to self-determination and that the community nurse develops the plan of care in collaboration with the client. Each client and her or his environment can be a learning situation; we acknowledge that people live in a variety of settings—from mansions to shipping containers with no electricity or running water. Some aspects of our work can also be confronting; debriefing with the nurse who you are working with is encouraged after visits, and the NUM is available to discuss and address any concerns and issues that you may have during the placement.

There may be situations in which it is not appropriate for you to accompany the community nurse on a visit. This could occur when a mother has postnatal depression, or if the nurse is working with a family where there is a child-protection issue or needing palliative care. Alternative arrangements will be made for you in these circumstances.

References

Centre for Health Equity Training, Research and Evaluation (CHETRE) . Guidelines: Core Functions and Services for Primary and Community Health Services in NSW. Online. Available http://www.phcconnect.edu.au/fact_sheets.htm. 2010 Accessed 14.01.10

Kemp LA, Comino EJ, Harris E. Changes in community nursing in Australia. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2005;49(2):307-314.

Ward D. Master of Primary Health Study Guide. Penrith: University Western Sydney; 1999.

Further reading

Centre for Health Equity Training, Research and Evaluation, University of New South Wales. Online. Available http://chetre.med.unsw.edu.au/.

NSW Health . Planning Better Health: Background Information. Online. Available http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/pubs/2004/pdf/pbh_booklet.pdf.

Community health information

Federal .http://www.health.gov.au.

Australian Capital Territory .http://www.health.act.gov.au.

New South Wales .http://www.health.nsw.gov.au.

Northern Territory .http://www.health.nt.gov.au.

Queensland .http://www.health.qld.gov.au.

South Australia .http://www.health.sa.gov.au.

Victoria .http://www.health.vic.gov.au.

Western Australia .http://www.health.wa.gov.au.

6.4 Day-surgery nursing

Alison Anderson

RN, Grad Cert Clinical Teaching

Clinical Nurse Specialist, Sydney Adventist Hospital

6.4.1 An overview of day-surgery nursing

While day surgery is usually considered a development of the 20th century its origins began in the late 1800s. Today, day-surgery units (DSUs) around the world are found in integrated centres in healthcare facilities, large or small, and as free-standing centres. Many focus attention on a wide range of surgical specialties, while others select a single specialty as their primary treatment focus. Day procedure units may deal with surgical procedures and/or medical and diagnostic procedures such as endoscopy or haematology.

The changes and growth in DSUs continue as a result of developments in anaesthetics, medications and improved surgical techniques. The past 20 years has seen the greatest changes in this specialty and patients benefit from reduced costs and recovery time, reduced time away from their family and work, an easy transition from admission to anaesthetics and theatre and discharge, and the satisfaction of being in a caring environment especially tuned to safe discharge in a shortened time frame.

6.4.2 Learning opportunities

Nursing in the DSU environment can provide a wide variety of learning opportunities for the undergraduate nurse, from enhancing assessment techniques, admission to discharge processes and specialist skills in theatre and/or recovery. No matter how many patients come through the doors each day, every student can be involved in and be part of a well-skilled team. You will have an opportunity to share with patients their journey through a precise surgical experience and enjoy knowing that you have taken part in the patient’s treatment plan. Specific learning opportunities include:

• Developing your skills in patient assessment in the preoperative stage in order to prevent patients from having an adverse outcome during surgery. In the DSU you will learn how to assess the patient and act on abnormal findings while understanding the needs of the specialty.

• Learning about new surgical procedures across many specialties. Some facilities allow nursing students in the operating theatre and recovery unit as well as in preoperative and discharge preparation.

• Learning about anaesthetics and pain management used for day patients, and what it is about day surgery that changes anaesthetic and analgesic requirements.

• Gaining skills in patient teaching in order to assist patients and carers understand the importance of and management of postoperative pain, nausea and vomiting, and post-discharge management.

• Developing skills in communication, prioritising work and working as part of a team.

6.4.3 Preparation for the placement

Before commencing the placement you should research the following:

• best practice guidelines for day-surgery facilities;

• current trends in anaesthetics for day patients, including local anaesthetic agents and blocks;

• surgical procedures relevant to DSUs (e.g., orthopaedic, gynaecology, ear, nose and throat surgery and endoscopy);

• nursing assessment and its application to the surgical patient;

• discharge planning for the day patient and common postoperative complications;

6.4.4 Challenges students may encounter

Students’ experiences vary widely dependent on the number and types of patients in the facility. You should find out what cases are performed, what the facility offers patients and then focus on one or two areas of interest.

Moving from a pre-admission clinic, to admissions, to postoperative recovery may be confusing and leave you with a fragmented experience. Working in one of these areas at a time will enhance your experience and provide a more settled and worthwhile learning environment.

Staff may feel pressured as a result of a variety of situations, and different healthcare professionals may be seen to come and go in the DSU, which can be distracting. Taken in context and with a well-trained mentor on hand, watching, questioning and learning can provide a positive experience.

Resources

Australian Day Surgery Nurses Association . Best Practice Guidelines for Ambulatory Procedures. Australian Day Surgery Nurses Association www.adsna.info.

6.5 Developmental disability nursing

Kristen Wiltshire

RN, RM

Nurse Learning and Development Officer, Hunter Residences, Ageing, Disability & Home Care (ADHC), Human Services, NSW

Bill Learmouth

RN

Nurse Manager Learning and Development, Hunter Residences, Ageing, Disability & Home Care (ADHC), Human Services, NSW

6.5.1 An overview of developmental disability nursing

Developmental disability services provide care to people with a disability of any age, in both large residential facilities and community settings. Both government and non-government disability services focus on supporting clients to lead valued, independent lives with the opportunity to participate fully in the community.

The services provided are comprehensive and include the provision of nursing care to people with complex support needs in areas of multiple disability and behaviour intervention. The majority of clients in residential facilities are severely intellectually disabled adults with complex and concurrent disabilities. These disabilities may include sensory impairment, lack of mobility or altered mobility exacerbated by the normal ageing process, epilepsy and other medical conditions and/or challenging behaviour. People with an intellectual disability may suffer from a range of health issues faced by the general community; however, their disability may put them at greater risk because of the difficulty of early identification and diagnosis. The role of nursing staff in recognising deviations from normal functioning is vital.

For some clients, the cause of their intellectual disability may have many health problems associated with it; for example, clients with Down’s syndrome are more likely to have cardiac and respiratory problems, thyroid disease, diabetes and coeliac disease. The complexity of the health needs of our clients requires a coordinated and multidisciplinary approach by a team of health professionals.

The rights of disabled people to make choices regarding the services they wish to participate in must be upheld. Consent for medical procedures must be given by a ‘person responsible’, who is nominated by the Guardianship Tribunal; a medical practitioner can intervene in emergency situations. Usually a range of services is available, including visiting specialists who see clients with medical problems. The clients can be treated and monitored on site, but in some circumstances they will be referred to the specialists in the general hospital system.

Many people with disabilities live in community homes and/or are cared for by families and will access a range of healthcare facilities, both private and public. It is an asset for nurses to develop experience in disability nursing in order to identify and provide nursing care when disabled clients present with their multiple health needs. In the general system, a high percentage of medical and nursing staff are inexperienced in dealing with both people with an intellectual and/or physical disability and their carers.

6.5.2 Learning opportunities

Disability services provide a microcosm of a whole range of learning opportunities. For example, students will have the opportunity to care for clients with disabilities and conditions that are rarely seen in the general public health system. These include syndromes such as Rett, congenital rubella syndrome, Dandy–Walker, cri-du-chat and cytomegalovirus.

The average age of the client population is also increasing and, in some cases, this average is increasing more quickly than that of the normal community. Issues such as mobility, depression, anxiety, dementia, osteoporosis, diabetes, heart problems and cancer all add to the complex nature of the care we provide.

Many of the clients exhibit ‘challenging behaviour’, which is behaviour that can interfere with the client’s or staff carer’s daily life experiences. Challenging behaviour is not an inevitable result of developmental disability, but it can contribute to social isolation and lack of opportunities for our clients. A significant emphasis is placed on identifying client’s lifestyle needs to reduce the frequency of challenging behaviour and enhance the lifestyle of the clients. Clients also have the opportunity to participate in activity centres for stimulating and diversional therapy.

6.5.3 Preparation for the placement

You are encouraged to:

• develop an awareness of the range of services available and the healthcare requirements of people with disabilities and their families;

• develop an understanding of the Disability Services Act and Standards;

• ensure that you have a criminal record clearance check prior to placement as well as the required immunisations.

6.5.4 Challenges students may encounter

The challenge for students is to understand the complexity of the health needs of people with a disability. Feeding, hydration and maintaining adequate nutrition are very important as many disabled clients have dysphagia (difficulty swallowing). Meeting the client’s mobility needs will often involve you using a range of equipment. Communication may be a challenge for you as many of the clients have limited or no verbal communication skills and rely on non-verbal communication, such as gestures, sign language and augmentative communication devices. Their verbal communication can also be limited to vocal sounds and/or limited vocabulary.

6.6 Drug and alcohol nursing

Richard Clancy

RN, MMedSc, BSocSc

Clinical Nurse Consultant, Mental Health and Substance Use, Hunter New England Health

Conjoint Lecturer, University of Newcastle

6.6.1 An overview of drug and alcohol nursing

Substance use is widespread within the community. Among your own family, friends and fellow students you may have noticed that different people will choose to use different substances; from caffeine, alcohol, nicotine and marijuana to amphetamines, opiates and hallucinogens. Most people who use substances are able to do so in a way that causes little or no noticeable harm to themselves or others. However, you will be aware that for some people substance use may lead to differing degrees of psychological, social, legal, financial and physical problems. Many people who experience problems with substances manage the situation themselves, while others seek assistance from drug and alcohol services.

Some members of the community hold preconceived ideas about the treatment offered at drug and alcohol services. These views probably reflect the diversity of opinions regarding substance use rather than being based on knowledge of the actual services offered. The reality is that health-funded drug and alcohol services follow government policy; the underpinning of these policies is harm minimisation. Harm minimisation strategies are based on the concept of accepting that substance use occurs at all levels in society and is unlikely to stop. One goal that is achievable is to reduce the harm caused by substance use. It is this premise that determines the drug and alcohol clinical services.

A clinical placement in drug and alcohol nursing may take place in a variety of settings, and each placement offers opportunities to observe and practice a new set of skills. Drug and alcohol services within each health service will offer different clinical placement opportunities, which may include inpatient and community detoxification, counselling services, harm-minimisation programs, pharmacotherapy programs and court diversion-treatment programs.

6.6.2 Learning opportunities

A clinical placement in the alcohol and other drugs sector provides a truly unique opportunity for students to learn first-hand about a range of interventions used in substance-use treatment, including counselling strategies such as cognitive behavioural approaches and motivational interviewing, as well as pharmacotherapies.

You will learn a good deal about the substances themselves and the issues experienced by people who use them. As a student nurse, you will observe some of the ethical dilemmas involved in treating chronic disorders with a behavioural component.

6.6.3 Preparation for the placement

It is important to reflect on your own views towards substances prior to commencing a placement in this field. As human beings, we, of course, have our views regarding different substances and people who use them. So reflect on questions such as:

It is also very useful to review some information on the brain’s reward pathway in relation to substance-use disorders to highlight the biological issues involved in these, along with an overview of substances themselves.

6.6.4 Challenges students may encounter

Some of the ethical dilemmas that you will encounter on clinical placement in this area may challenge your values and decision-making processes. These dilemmas will also provide you with valuable practical experiences in managing ethical issues that you will face throughout your future career. Motivation to change varies considerably between individuals who present for treatment. One of the challenges you will face in this placement will be the issue of seeing many clients who may be intelligent individuals, but who repeatedly use substances despite a range of negative consequences. Another challenge you will face will relate to your own views about your own substance use and that of your friends.

6.7 Emergency nursing

Leanne Horvat

RN, RM, BN, Cert Emergency, Grad Dip Midwifery, MNurs (Nurs Prac)

Clinical Nurse Consultant, Emergency Services, St George Hospital

Conjoint Lecturer, University of Newcastle

6.7.1 An overview of emergency nursing

The Emergency Department (ED) is a unique, dynamic and challenging specialty practice area in which you will provide care for patients from across the lifespan, including neonates, paediatrics, adults and the elderly. Emergency nursing as a specialty practice has continued to evolve and change. The emergency nurse is a highly experienced clinician, often being the first point of contact for the patient in the hospital setting (Fry 2007a).

Emergency nurses are required to manage multiple tasks simultaneously, utilising expert clinical assessment and organisational skills, while maintaining good communication and liaison skills in an often chaotic and overcrowded environment. The most important feature of emergency nursing is the ability to manage critically ill patients and those who are undiagnosed, who often present with only subtle signs and symptoms (Fry 2007a).

6.7.2 Learning opportunities

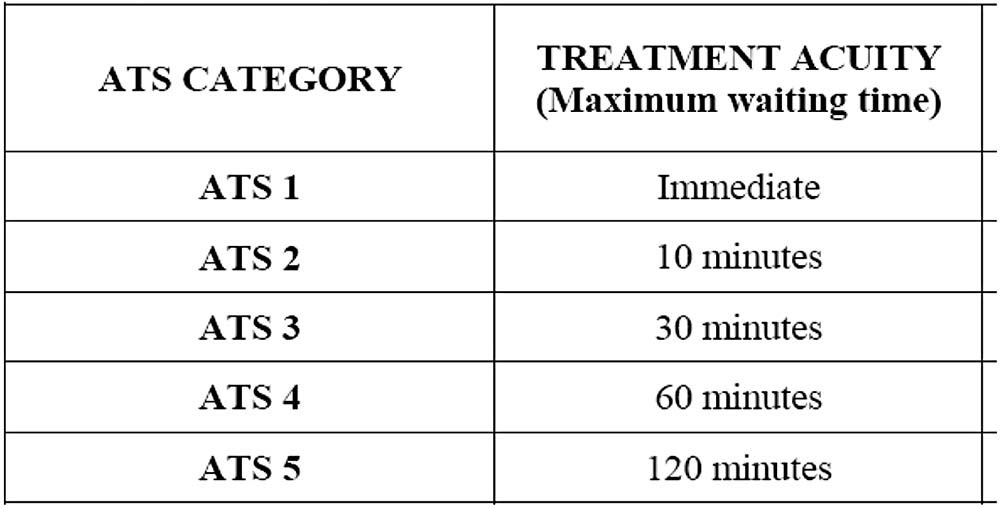

As a student nurse you will be able to observe one of the most pivotal nursing roles in the ED, this being the role of triage nurse. Triage is the process of sorting patients as they arrive to the ED for care. It is the triage nurse’s responsibility to identify quickly those patients who need immediate or urgent medical attention and those who are safe to wait (Fry 2007b, pp 84–85). Primarily, the triage nurse role includes preparing a brief (3–5 minutes) nursing assessment by collecting fundamental information including objective data (visual observation of the patient and their vital signs) and subjective data (why the patient is presenting or their primary complaint). The triage nurse then allocates the patient into one of five triage categories according to the Australasian Triage Scale (ATS) (Fry 2007b, pp 85–87; ACEM 2006) see Figure 6.1.

Another learning opportunity while working in the emergency setting will be to observe the critical care aspect of resuscitation and trauma management. You may be able to assist in the care and observation of patients who present following blunt or penetrating injuries that result from motor vehicle accidents, accidental falls, assaults, self-harm, firearm or stabbings to impaling or crush injuries. These patients, who require extended resuscitation and trauma care, often have high mortality and morbidity outcomes (Farrow et al. 2007, pp 673–679). As a student nurse you must prepare yourself for seeing both the best and the worst life has to offer, as well as seeing patients and their family members in turmoil.

6.7.3 Preparation for the placement

Prior to undertaking an ED placement, consider how you would manage the care of the following people:

• a 56-year-old man presents with central chest pain and shortness of breath;

• an 80-year-old lady presents via ambulance following a fall onto the floor six hours ago and is unable to weight bear;

• a 16-year-old girl who presents with abdominal pain after being involved in a motor vehicle crash;

• a 2-year-old child has fallen of the slippery-dip, hit his head and presents with a small laceration above his eyebrow;

• a 65-year-old man presents via ambulance following a collapse, and is in cardiac arrest.

How are you going to manage the immediate care of each of these individual patients? What clinical assessment are you going to undertake? How are you going to determine the potential for rapid deterioration of any one of these patients? These are some of the questions you should consider before you start your clinical placement in the ED.

The emergency nursing assessment process includes several key steps, which are discussed separately here, but it is important to know that often these steps may be done simultaneously (Curtis et al. 2009). You should be familiar with each of these steps before commencing your placement:

Step 1: History taking

Focusing on the chief complaint to determine the severity of the patient’s illness and any need for immediate interventions is of paramount importance. You may need to question the patient and/or their family/carer about pain history, associated symptoms, past history, medications, allergies, mechanism of injury, current treatments and social history in order to gain key information about the patient’s illness or injury (Curtis et al. 2009, p. 132).

Step 2: Potential ‘red flags’

The first ‘red flag’ is to determine any threat to life or limb that indicates immediate medical intervention is needed. You will notice that emergency nurses are able to make this determination within seconds of coming into contact with a patient. You must utilise a combination of findings that may indicate severe illness, which may include clinical signs (abnormal vital signs), medical history (such as chronic renal failure or heart disease) or time-sensitive presentations (chest pain or loss of consciousness). These ‘red flags’ may indicate the need for urgent treatment and/or investigations to commence (Curtis et al. 2009, pp 132–133).

Step 3: Clinical examination

The clinical examination follows the ABCD mnemonic, commencing with initial threats to airway, breathing, circulation and disability (neurological function) (Curtis et al. 2009, p. 134). If nothing proves to be imminently life-threatening, a more focused assessment can continue. You must then continue with a full set of vital signs including blood pressure (BP), pulse (P), respirations (R), temperature (T) and oxygen saturations (SpO2) and a full head-to-toe assessment that focuses on the affected body system (Farnsworth & Curtis 2007, pp 93–95). For example, the 56-year-old man who presented with central chest pain and shortness of breath would initially be assessed for threats to his ABCD, followed by a more focused assessment of his cardiac and respiratory systems.

Step 4: Investigations

Laboratory and other diagnostic tests are obtained during the patient assessment, which may support or rule out diagnoses and assist with a definitive plan of care. Determining which laboratory and diagnostic tests should be ordered is not primarily a nursing responsibility, but in some facilities you will find that advanced clinical nurses are able to order specific tests against local departmental policies or standing orders (Curtis et al. 2009, p. 134).

There are also other tests that the student nurse can be involved in during the initial assessment, to either confirm or rule out a diagnosis. As a student nurse you will be expected to attend electrocardiograms (ECGs) for patients who present with chest pain, cardiac arrhythmias or collapse, as well as blood glucose levels (BGLs) for diabetic patients, those who present after a collapse or loss of consciousness, nausea and vomiting, and neonates (Farnsworth & Curtis 2007, p. 96).

Step 5: Nursing interventions

Nursing interventions may occur simultaneously as you are taking your history and attending to your clinical examination. As a student nurse you may be assisting your patient into their hospital gown and talking to them about their chief complaint, while taking note of their general colour, mobility, position of comfort and baseline vital signs.

Simple, effective interventions, such as pain relief, application of oxygen, splinting of injured limbs or the need for a cannula or bloods will become apparent very quickly during your assessment. These interventions often occur concurrently and, as the student nurse, it is important to frequently reassess your patient to determine whether your interventions have been successful, as well as any potential deterioration in your patient’s condition (Curtis et al. 2009, p. 134).

6.7.4 Challenges students may encounter

There are many situations in the ED that you may find challenging. However, caring for special populations, such as those listed below, is perhaps the most important challenge and one you need to prepare for carefully prior to the placement:

References

ACEM . Policy on the Australasian Triage Scale. Australasian College of Emergency Medicine. Online. Available http://www.acem.org.au/media/policies_and_guidelines/P06_Aust_Triage_Scale_-_Nov_2000.pdf. 2009 Accessed 02.01.09

Curtis K, Murphy M, Hoy S, Lewis MJ. The emergency nursing assessment process – a structured framework for a systematic approach. Australasian Emergency Nursing Journal. 2009;12:130-136.

Farnsworth L, Curtis K. Patient assessment and essential nursing care. In: Curtis K, Ramsden C, Friendship J, eds. Emergency and Trauma Nursing. Sydney: Mosby; 2007.

Farrow N, Caldwell E, Curtis K. An overview of trauma. Cited in In: Curtis K, Ramsden C, Friendship J, eds. Emergency and Trauma Nursing. Sydney: Mosby; 2007.

Fry M. Overview of emergency nursing in Australasia. Cited in In: Curtis K, Ramsden C, Friendship J, eds. Emergency and Trauma Nursing. Sydney: Mosby; 2007.

Fry M. Triage. Cited in In: Curtis K, Ramsden C, Friendship J, eds. Emergency and Trauma Nursing. Sydney: Mosby; 2007.

6.8 General practice nursing

Elizabeth J Halcomb

RN BN(Hons), Grad Cert, IC, PhD, FRCNA

Senior Lecturer, School of Nursing & Midwifery, University of Western Sydney

6.8.1 An overview of general practice nursing

General practice nursing is a well-developed specialty area in the United Kingdom and New Zealand, and an emerging specialty in Australia. Although nurses have worked in Australian general practice for many years, in recent years the number of practice nurses has increased and their roles have developed (Halcomb et al. 2005). This has largely been the result of Federal Government initiatives that have provided additional funding for the employment of practice nurses and allowed practice nurses to claim Medicare items for certain procedures (Halcomb et al. 2008).

6.8.2 Learning opportunities

In Australia it is expected that you will work with a registered or enrolled nurse for the duration of your placement in general practice. In the New Zealand context only registered nurses fulfil the role of practice nurses. Although you may have a strong desire to gain hands-on experience, the specialised nature of the nursing role in general practice and the short consultation duration means that you may undertake significant periods of observation. It is important for both patient safety and your own professional status that you do not feel pressured to undertake duties unsupervised by a registered nurse or beyond your scope of practice (Australian Nurses Federation 2008; Nursing Council New Zealand 2008). General practice is an important learning environment for undergraduates as it provides an opportunity to participate actively in the frontline delivery of primary care. As such, it allows students to develop an appreciation of the complexity of health issues that face the community and the health services available in the general practice setting. This will assist in broadening the outlook not only of those students who wish to pursue a career in community or practice nursing, but also of those who seek employment in the acute sector. Given the increasing emphasis on primary care, now is an exciting time to be introduced to the specialty of practice nursing as there are significant opportunities to contribute to the health of the community, as well as to develop a career pathway and to participate in the advancement of the specialty.

Approximately 85 per cent of Australians visit a general practitioner annually (Britt et al. 2008). Unsurprisingly, increased service use is seen in those of advanced age or with chronic illness and complex health needs. Given the shift from hospital-based to community-based care, patients seen in contemporary general practice often have more complex health needs than has been the case historically. However, the demographics of the local community and, more specifically, the practice population will impact upon the nature of clinical presentations within the general practice that you may visit. It is likely that you will be exposed to a variety of clinical areas during the placement, including childhood, travel and influenza immunisation, women’s health checks, childhood health assessments, wound dressings, lifestyle risk-factor monitoring and chronic disease management.

6.8.3 Preparation for the placement

In preparation for a placement in general practice, you would benefit from developing an understanding of the way in which general practice services fit within the broader context of the health system. This understanding will allow you to better appreciate the role that general practice nurses play across the spectrum of health and illness. Given the unique environment and models of service delivery seen in general practice, preparation for the placement should also promote your knowledge of the competency standards of registered and enrolled nurses in general practice and the legal requirements within which nurses’ practice (Australian Nurses Federation 2008; Nursing Council New Zealand 2007).

6.8.4 Challenges students may encounter

A major challenge that you may encounter is the difference in the environment of general practice compared to that of acute-care settings. In general practice, teams are often small and rely on each other to provide support and advice. This requires team members to work closely together and communicate with each other to optimise service delivery. While such an environment may foster the autonomy of the nurse in their practice, it may also create a degree of professional isolation (Halcomb et al. 2005). For students, it may be challenging to work in the general practice environment with a small group of nurse mentors for support. Before commencing a placement in general practice, you should be aware of key contacts, both internal and external to the practice, that can provide you with support should it be required.

Given the sensitive nature of some consultations it may not be appropriate for you to observe at all, or it may be appropriate to seek the patient’s permission for you to observe. The appropriateness of your presence needs to be based on the nature of the consultation and the wishes of the patient. Examples of consultations that might not be appropriate for you to observe include cervical smears, when the nurse is working with patients with significant mental health issues, or sexual health consultations with vulnerable groups. As much of the success of care based on general practice is based on the relationship between patients and general practices it is vital that the presence of students does not have a detrimental effect on this relationship.

References

Australian Nurses Federation . Competency Standards for Nurses in General Practice. Online. Available www.anf.org.au/nurses_gp/.

Britt H., et al. General Practice Activity in Australia 2007–08. General Practice Series No. 22 Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2008.

Halcomb EJ, Davidson P, Daly J, Yallop J, Tofler G. Nursing in Australian general practice: directions and perspectives. Australian Health Review. 2005;29(2):156-166.

Halcomb EJ, Davidson PM, Salamonson Y, Ollerton R. Nurses in Australian general practice: implications for chronic disease management. Journal of Nursing and Healthcare of Chronic Illness, in association with Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2008;17(5A):6-15.

Nursing Council New Zealand . Competencies for Registered Nurses. Wellington: Nursing Council New Zealand; 2007.

Nursing Council New Zealand . Guideline, Direction and Delegation. Wellington: Nursing Council New Zealand; 2008.

General practice nursing information

Australian Practice Nurses Association .http://www.apna.asn.au/.

Australian General Practice Network (AGPN) Practice Nursing Program .http://generalpracticenursing.com.au/.

Australian National Divisions of General Practice .http://www.gp.org.au/.

New Zealand College of Practice Nurses, New Zealand Nurses Organisation (NZNO). http://www.nzno.org.nz/groups/colleges/college_of_practice_nurses.

6.9 Indigenous nursing

Vicki Holliday

RN, Grad Dip in Indigenous Health Studies, Master of Indigenous Health Studies, Grad Cert Educational Studies (Higher Education)

Program Coordinator, Integrated Chronic Care for Aboriginal People, Community Health Strategy, Hunter New England Health Service

6.9.1 An overview of Indigenous nursing

There have been many reports, publications, texts and media stories about the poor status of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health. The opportunity to undertake a placement in an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander Community Controlled Health organisation and/or in a clinical area that provides health services to Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples is valuable learning opportunity that will help you to better understand the culture, history and health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. This will help you in your journey towards becoming culturally safe.

Your clinical placement could be in an Aboriginal Medical Service (AMS) or a public health facility or service or both. AMSs are Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations (ACCHOs), and are governed by a Board that is elected by the local community. AMSs are funded by Commonwealth and State health and provide primary healthcare services based on a holistic approach. Health services offered by AMSs may vary from service to service, but there are commonalities. For example, the service planning is person-and community-centred and based on community need.

6.9.2 Preparation for the placement

As a student the aim is to learn as much as you can from the local Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander community and those that provide services to the community. It is important to research the services and community prior to commencing the placement to ensure that you have an understanding of the protocols for the local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Community. You might like to consider seeking advice from Aboriginal health workers, Aboriginal nurses, Indigenous advisors at the university or other members of the community or talk to other students that have completed clinical placements in that or a similar organisation. This will give you an understanding of the community and/or organisation you will be working in.

6.9.3 Challenges students may encounter

It is important to approach clinical placement in an Indigenous nursing context with an open mind. You may well find your concept of health and healthcare challenged by your experiences.

In order to meet these challenges and to be effective in delivering appropriate care to Indigenous people, you will need:

• awareness of important Indigenous issues, such as cultural differences, specific aspects of Indigenous history and its impact on Indigenous peoples in contemporary Australian society;

• the skills to interact and communicate sensitively and effectively with Indigenous clients;

• the desire or motivation to be successful in your interactions with Indigenous peoples, in order to improve access, service delivery and client outcomes (Farrelly & Lumby 2009).

6.9.4 Learning opportunities

The type of placement will vary depending on the services offered by your host. You may have an opportunity to work in clinics at the AMS, attend outreach clinics, accompany an Aboriginal health worker or community nurse on home visits or attend community education programs. Occasionally, during these placements there will be no registered nurses to work with you and you may be asked to work with other health-service providers, such as Aboriginal health workers who have a wealth of knowledge about both Aboriginal health and the community.

Ensure that you are respectful of local protocols and practices and if you are unsure of what they are it is best to ask. For example, some organisations may require you to wear a uniform and others may not. Ensure that if a uniform is not required you know what clothing is appropriate. During the placement you may be asked to wait in a different area or not attend a home visit or to leave the room. This could be because of traditional or cultural practices, such as the care of an elder, or men’s or women’s business, and should not be taken as a personal issue.

So what does this all mean to you as a student nurse? Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health is everybody’s business. A culturally safe workforce will, in the short, medium and the long term, improve the health outcomes for Indigenous people by providing culturally appropriate healthcare services. This will, in turn, improve access to those services and we all play a role in making that happen.

Go into your placement without any assumptions or expectations. Use the placement as an opportunity to learn as much as you can, not only from a clinical perspective, but from a cultural and historical perspective to broaden your knowledge about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. In the long term it is you and your peers that will be playing a major role in closing the gap in the life expectancy between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and non-Indigenous people.

References

Farrelly T, Lumby B. A best practice approach to cultural competence training. Aboriginal and Islander Health Worker Journal. 2009;33(5):14-22.

Useful reading

Eckermann A., et al. Binan Goonj: Bridging Cultures in Aboriginal Health. 3rd edn Chatswood, Sydney, NSW: Elsevier; 2010.

6.10 Intensive care nursing

Paula McMullen

RN, PhD, BSN, ICC, MHPEd

Senior Lecturer, University of Tasmania

6.10.1 An overview of intensive care nursing

The intensive care unit (ICU) is an environment that cares for critically ill or injured patients as well as the patient’s family and/or significant others. Patients in ICU have at least one organ system failure if not multiple organ failure. These life threatening conditions warrant close monitoring (for example: invasive monitoring of the cardiovascular, respiratory and neurological systems). Most ICU patients require life support devices such as ventilation, inotropic therapy, renal replacement therapy (RRT) to name a few. Because of the serious nature of the patient’s illness, they are nursed on a 1 : 1 nurse-patient ratio.

6.10.2 Learning opportunities

The ICU environment provides nursing students with excellent opportunities to learn and develop their nursing practice. As patients in the ICU are often totally dependent on others for holistic care, this provides a perfect opportunity to fine tune fundamental skills, including patient hygiene, range of motion exercises, positioning of patients, assisted mobilisation and, of course, meeting the psychosocial needs of the patient and family. Astute physical assessment skills are a must in the critical care environment. It is imperative that the nurse identifies subtle changes in the patient’s vital signs, pathology, etc., in order to develop critical thinking skills, engage in problem-solving and make accurate clinical judgements. The ICU setting is also diverse in that it caters to patients across the age continuum and provides opportunies for working collaboratively with multidisciplinary teams. It is an area at the cutting edge of biomedical technology and research. Therefore it provides a haven of opportunities to expand your nursing repertoire.

6.10.3 Preparation for the placement

There are several things you can do in preparation for your placement in order to optimise your clinical experience in ICU. First and foremost, make sure that you have a sound understanding of anatomy and physiology. Your physical assessment skills will be put to the test. Before you go to your ICU clinical placement, review and practice the following:

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access