CHAPTER 2 Information needs, asking questions and some basics of research studies

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

This chapter will provide background information that you need to know in order to understand the details of the evidence-based practice process that follow in the subsequent chapters of this book. In that sense, this chapter is a somewhat diverse but important collection of topics. We start by describing the types of clinical information needs health professionals commonly have and discuss some of the methods that health professionals use to obtain information to answer their needs. As we saw in Chapter 1, converting informational needs into an answerable, well-structured question is the first step in the process of evidence-based practice and, in this chapter, we will explain how to do this. We then explain the importance of matching the type of information you need with the type of study design that is most appropriate to answer your question. As part of this, we will introduce and explain the concept of ‘hierarchies of evidence’ for each type of question. In the last sections of this chapter, we will explain some concepts that are fundamental to the critical appraisal of research evidence, which is the third step in the evidence-based practice process. The concepts that we will discuss include internal validity, chance, bias, confounding, statistical significance, clinical significance and power.

Clinical information needs

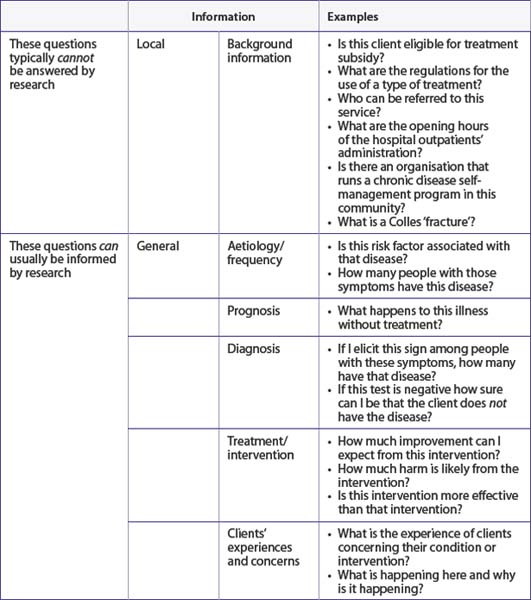

Health professionals need information all the time to make decisions, to reassure clients, to make practical arrangements and so on. Some of the information that we need can be usefully assembled from research and some of it cannot. Table 2.1 provides examples of some of the obvious types of information that can or cannot be gathered from research. This book will help you to learn how to deal with information needs that can be answered to some extent by research. Along the way we will also discuss the types of information that come from clients and the types of information that come from clinical experience. When we consider these together—information from research, clients and experience— we are working in an evidence-based practice framework.

Dealing effectively with information needs

The size of the problem

The clinical literature is big. Just how big is staggering. There are thousands of new studies published hourly. For example, randomised controlled trials are published at the rate of 20,000 per year. That is roughly 50–60 per day, or one every 20–30 minutes. Worse than that, randomised controlled trials represent a small proportion (less than 5%) of the research that is indexed in Medline and, as you will see in Chapter 3, it is just one of the databases that are available for you to search in to find evidence. This means that the accumulated literature is a massive haystack in which are embedded some important needles we have to find. One of those needles of information might be the difference between effective or ineffective (or even harmful) care for your client. One of the purposes of this book, then, is to help you find needles in haystacks.

Noting it down

How should we do this? One way is to keep a little book in which to write them down in your pocket or handbag. Date and scribble. A more modern way is electronically, of course, using a personal digital assistant (PDA) or computer (if simultaneously making client records). Some of us tell the client what we are doing:

In Chapter 1, we discussed the general process of looking up, appraising and applying the evidence that we find. But also remember to keep track (in other words, write it down!) of the information that you found and how you evaluated and applied it. In the end, the information that is found might result in you changing (hopefully improving) your clinical practice. The way it does this is often uncoupled from the processes you undertook, so it takes some time to realise what led you to make the changes—often systematic—to the way you do things. Sometimes the research information just reassures us that we are on the right track but this is important also.

Different ways of obtaining information: Push or pull? Just-in-case or just-in-time?

Push: just-in-case information

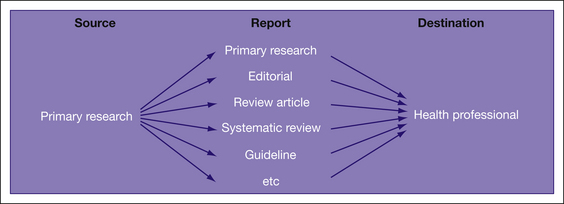

Figure 2.1 shows some examples of information that can be pushed. Other sources of ‘push’ information include conferences, professional newsletters, textbooks and informal chats to colleagues and other people from other professional groups.

As can be seen, there are many ways that a piece of research can percolate through to you as a health professional. The picture is actually more complex than this: what is picked up for review, systematic review and so on is determined by a number of different factors, including which journal the primary data were first published in, how relevant readers think it is and how well it fits into the policy being formulated or already in existence. There are, in fact, different sorts of information that we might consider accessing and this is explained in detail in Chapter 3 (see Figure 3.1). But this is only the start. All these methods rely on the information arriving at your place of work (or home, post box, email inbox etc). Then it has to be managed before it is actually put into practice. How does this happen? There are a number of different stages that can be considered and these are explained in Table 2.2.

TABLE 2.2 The processes involved in making sure that just-in-case information is used properly to help clients

| Task | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Read the title | Decide whether something is worth reading at all. |

| Read the abstract | |

| Read the full paper | We have obviously not tossed this paper aside (that means we have turned the page). |

| Decide if it is … | |

| a. relevant | A lot of research is not aimed at us (as health professionals looking for better information to manage our clients). Much of it is researcher-to-researcher information. Just some of it is information that we think might be useful to us, either now or in the future when this might become part of everyday practice. |

| b. believable | Methodologically sound. That means the information is not biased to the extent that we cannot believe the result. This is explained further later in this chapter and in Chapters 4–12. |

| Wonder if the technique is available | A lot of research does not spell out the treatment, diagnostic procedure or definitional terms adequately so that we can simply put the research into practice—even if we believe it! |

| Store the paper so we can recall it when the right client comes along | Different health professionals do this in different ways: Most health professionals do the last. And then forget! |

| Ensure we have the necessary resources to incorporate the research into our practice | There may be prerequisites, such as availability of resources and skills to carry it out or perhaps some policy needs to be instituted before this can happen. |

| Persuade the client | … that this is the best management … |

Clearly this is not an easy process. There are many steps where the flow can be interrupted. All the steps have to happen for the research to run the gauntlet through to the client. One solution is to use one of the abstracting services. One of these is the Evidence Based journal series (see http://ebm.bmj.com/). This type of service is described in depth in Chapter 3 but, in a nutshell, these journals only provide reports of previous research (that is, they contain no primary research). Papers are reported only if they survive a rigorous selection process that begins with a careful methodological appraisal, and then, if the paper is found to be sufficiently free of bias, it is sent for appraisal by a worldwide net of health professionals who decide if the research is relevant. The resultant number of papers that is reported in each discipline is surprisingly small. In other words, only a few papers are not too biased and also relevant! Happily for health professionals, there is another option.

Pull: just-in-time information

Pull is advertising jargon for the way potential customers go looking for information, rather than simply waiting for it to be pushed to them. In this context, it is information that the health professional seeks in relation to a specific question arising from their clinical work. This gives it certain characteristics. This is illustrated in Table 2.3 using the five As that were introduced in Chapter 1 as a way of simply describing the steps in the evidence-based practice process.

TABLE 2.3 Processes involved in just-in-time information: the five As

| Task | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Ask a question: re-format the question into an answerable one | This ensures relevance—by definition! |

| Access the information: searching | Decide whether to look now (in front of the client) or later. Searching is a special skill, which is described in Chapter 3. |

| Appraise the papers found | We talk about this (in fact, we talk about this a lot!) in Chapters 4–12. |

| Apply the information | This means with the client who is in front of you. |

| Audit | Check whether the evidence-based practice processes that you are engaged in are working well. |

How often do we ask questions? Is this something that we can aspire to realistically? Most health professionals are worried that they do not ask questions enough. Relax. You do. Studies have been undertaken in a number of settings (all to do with doctors, sadly) to show that they ask questions much more than they thought they did. For example, a study undertaken in Iowa, USA, examined what questions family doctors working in the community asked during the course of their work. Just over 100 doctors asked >1100 questions over 2.5 days, which is approximately 10 each.1 A similar Spanish study found that doctors had a good chance (nearly 100%) of finding an answer if it took less than 2 minutes, but were much less likely to do so (<40%) if it took 30 minutes.2 A study of doctors found that they are more likely to chase an answer if they estimate that an answer exists, or if the information need is urgent.3 Nurses working in a similar setting were more likely to ask someone or look in a book in order to answer their questions.4 Despite advances in electronic access, health professionals do not seem to be doing well at effectively seeking answers to clinical questions.5 If we are not able in the hurly burly of daily clinical practice to look up questions immediately, it is important (as we mentioned earlier in the chapter) to write them down.

How to convert your information needs into an answerable clinical question

Let us look at how we can take our clinical information needs and convert them into answerable clinical questions which we can then effectively search to find the answers to. You may remember from Chapter 1 that forming an answerable clinical question is the first step of the evidence-based practice process. Asking a good question is central to successful evidence-based practice. A focussed, well-constructed question typically has four components,6 which can be easily remembered using the PICO mnemonic:

Intervention or issue

The term intervention is used here in its broadest sense. It may refer to the intervention (that is, treatment) that you wish to use with your client—for example, ‘In people who have had a stroke, is home-based rehabilitation as effective as hospital-based rehabilitation in improving ability to perform self-care activities?’ In this case, home-based rehabilitation is the intervention that we are interested in. Or, if you have a diagnostic question, this component of the question may refer to which diagnostic test you are considering using with your clients—for example, ‘Does the Mini-Mental State Examination accurately detect the presence of cognitive impairment in older community-living people?’ In this example, the Mini-Mental State Examination is the diagnostic test that we are interested in. Or, if you have a question about prognosis, you may sometimes wish to specify a particular factor or issue that may influence the prognosis of your client—for example, in the question ‘What is the likelihood of hip fracture in women who have a family history of hip fracture?’, the family history of hip fracture is the particular factor that we are interested in. If you want to understand more about clients’ perspectives you may want to focus on a particular issue. For example, in the question ‘How do adolescents who are being treated with chemotherapy feel about hospital environments?’, the issue of interest is adolescent perceptions of hospital environments.

Outcome(s)

This component of the question should clearly specify what outcome (or outcomes) you are interested in. For some outcomes you may also need to specify whether you are interested in increasing the amount of the outcome (such as the score on a functional assessment) or decreasing it (such as the reduction of pain). In the stroke question example above, the outcome of interest was an improvement in the ability to perform self-care activities. As you will see in Chapter 14, shared decision making is an important component of evidence-based practice and it is important, where possible, to involve your client in choosing the goals of intervention that are most important to them. As such, there will be many circumstances where the outcome component of your question will be guided by your client’s preferences.

The exact way that you should structure your clinical question varies a little depending on the type of question that you have. This is explained more in the relevant chapter—Chapter 4 for questions about the effects of intervention, Chapter 6 for diagnostic questions, Chapter 8 for prognostic questions and Chapter 10 for qualitative questions.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree