Chapter 2 Influences on health

Overview

Chapter 1 showed that there is a wide range of meanings attached to the concept of health, and different perspectives offered by the scientific medical model and social science. It emphasized the importance of social factors in the construction and meaning of health. This chapter shows how the major influences on mortality and morbidity are social and environmental factors. It summarizes recent research which suggests that there are inequalities in health status between groups of people which reflect structural inequalities in society such as social class, gender and ethnicity.

Determinants of health

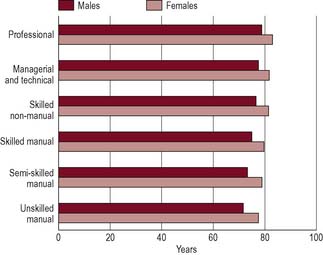

Since the decline in infectious diseases in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the major causes of sickness and death are now circulatory disease, including coronary heart disease (CHD) and stroke (36%), cancers (27%) and respiratory disease (14%) (Office of National Statistics 2007a). In the UK increased longevity and the current life span of women to 81 years and men to 76 years account for the increase in degenerative diseases in the population as a whole. Despite the increase in life expectancy, epidemiologists who study the pattern of diseases in society have found that not all groups have the same opportunities to achieve good health and there are population patterns which make it possible to predict the likelihood that people from different groups will die prematurely.

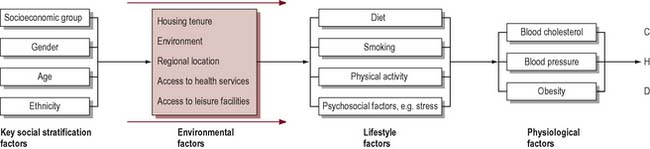

In trying to determine what affects health, social scientists and epidemiologists will seek to compare at least two variables: firstly, a measure of health, or rather ill health, such as mortality or morbidity; and, secondly, a factor such as gender or occupation that could account for the differences in health. Of course, effects on health can be due to several variables interacting together. For example, research into CHD has linked a large number of factors with the incidence of the disease: high levels of blood cholesterol, high blood pressure, obesity, cigarette smoking and low levels of physical activity. Other research indicates there may be links between CHD and psychosocial factors, such as stress and lack of social support, depression and anger (Stansfield & Marmot 2001). Many studies have also tried to establish whether there is a coronary-prone personality that is competitive, impatient and hostile (known as type A). We also know that mortality from CHD is higher among lower socioeconomic groups, among men rather than women, and among South Asians (Department of Health 2000). Figure 2.1 illustrates in a simple form how health status can be accounted for not by one variable, but by many factors interacting together. It shows that some factors have an independent effect on health or they may be mediated by other intervening variables. Whilst physical inactivity, smoking and raised blood cholesterol are the major risk factors for CHD (Britton & MacPherson 2000), it is important to look ‘upstream’ and understand the causes of these causes and their roots in the social context of people’s lives.

What is clear is that ill health does not happen by chance or through bad luck. The Lalonde report, published in Canada in 1974, was influential in identifying four fields in which health could be promoted:

Genetic factors remain largely unalterable and what limited scope there is for intervention lies in the medical field. Chapter 1 outlined McKeown & Lowe’s work (1974) which showed that medical interventions in the form of vaccination had remarkably little impact on mortality rates. This suggests that factors other than the purely biological determine health and well-being and that probably the greatest opportunities to improve health lie in the environment and individual lifestyles.

Lifestyles are frequently the focus of health promotion interventions. Figure 2.2 shows a whole range of factors that may influence smoking behaviour. Take another of the factors implicated in coronary heart disease such as nutrition and identify the influences on that health behaviour.

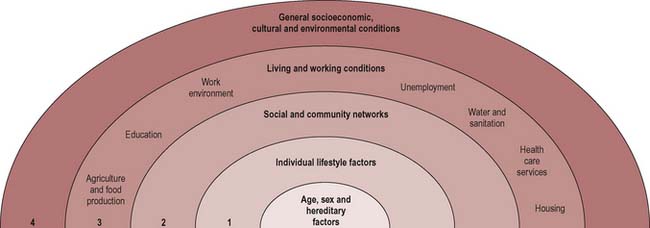

Dahlgren & Whitehead (1991) thus talk of ‘layers of influence on health’ that can be modified (Figure 2.2):

Social class and health

Most research which has sought to identify the major determinants of health and ill health has focused on the links between social class and health. A report was published of a Department of Health and Social Security working group on inequalities in health (Townsend & Davidson 1982). The report, which is known as the Black report, after the group’s chairman, Sir Douglas Black, provided a detailed study of the relationship between mortality and morbidity, and social class.

The terms social class, social disadvantage, socioeconomic status and occupation are often used interchangeably. The classification of social class derived from the Registrar General’s scale of five occupational classes ranging from professionals in class I to unskilled manual workers in class V. This was largely unchanged from 1921 (class III was divided into manual and non-manual work in 1971). From 2001 the National Statistics Socio-Economic Classification (NS-SEC) has been used for all official statistics and surveys (Table 2.1).

Table 2.1 Social class classification

| 1. | Higher managerial and professional |

| 1.1 | e.g. company directors, bank managers, senior civil servants |

| 1.2 | e.g. doctors, barristers and solicitors, teachers, social workers |

| 2 | Lower managerial and professional |

| e.g. nurses, actors and musicians, police, soldiers | |

| 3 | Intermediate |

| e.g. secretaries, clerks | |

| 4 | Small employers and own-account workers |

| e.g. publicans, playgroup leaders, farmers, taxi drivers | |

| 5 | Lower supervisory, craft and related occupations |

| e.g. printers, plumbers, butchers, train drivers | |

| 6 | Semi-routine occupations |

| e.g. shop assistants, traffic wardens, hairdressers | |

| 7 | Routine occupations |

| e.g. waiters, road sweepers, cleaners, couriers | |

| 8 | Never worked and long-term unemployed |

The Black report and a later report commissioned by the Health Education Authority, The Health Divide (Whitehead 1988), found significant differences in death rates between socioeconomic classes. More recent reports (Acheson 1998) draw together data which show that, far from ill health being a matter of bad luck, health and disease are socially patterned with the more affluent members of society living longer and enjoying better health than disadvantaged social groups. Although the health of the population has steadily improved, there is still a strong relationship between socioeconomic group and health status. This is evident in life expectancy, infant mortality, causes of death, prematurity and long-standing illness.

The extent and nature of health inequalities

Infant mortality

Causes of death

Figure 2.3 shows that there are substantial differences in life expectancy according to social class. Although infant deaths are declining, children from manual backgrounds are more likely to die in the first year of life or from accidental injury. Low birth weight is probably the most important predictor of death in the first month of life and this is clearly class-related, with two-thirds of babies under 2500 g born to mothers in social class V (Office of National Statistics 2007b). Although it is common to talk of ‘diseases of affluence’ such as CHD being the major killers in contemporary Britain, most disease categories are more common among lower socioeconomic groups. Particularly large differentials have developed for respiratory disease, lung cancer, accidents and suicide. An exception to this is death rates from breast cancer, which is evenly distributed across social groups. People from lower socioeconomic groups also experience more sickness and ill health. Measures of mental health and well-being also reflect a social gradient (Bromley et al 2005). This pattern of class and health gradient is thus visible in many ways including death rates, cause of death and reports of ill health.

Source: National Statistics website: www.statistics.gov.uk. Crown copyright material is reproduced with the permission of the Controller Office of Public Sector Information (OPSI).

In our companion book Public Health and Health Promotion: Developing Practice (Naidoo & Wills 2005) we discuss the determinants developing practice of health in more detail.

The most immediate causes of socioeconomic inequalities in health have been summarized by Macintyre (2007) as:

Income and health

In the UK better health is strongly associated with income. It is estimated that in the UK 10 million live in poverty, defined as having incomes below half the national average after allowing for housing costs (Department of Work and Pensions 2005). Those most likely to be in this category are the unemployed, pensioners, lone parents, families with three or more children and the low-paid.

Poverty can affect health directly by, for example, children not having enough to eat, eating a high-processed diet and limited access to food outlets. Across the UK dietary initiatives such as breakfast clubs, cookery clubs and community cafés promote healthy eating in low-income communities (for an example, see www.communityfoodandhealth.org.uk).

Housing and health

Frank Dobson, briefly Minister for Health in 1997, remarked: ‘everyone with a grain of sense knows that it’s bad for your health if you don’t have anywhere to live’. The issues of housing stock, dampness, inadequate heating and energy efficiency are recognized as key determinants of health (Department of Health 1999 paras. 4.28–4.31).

Cold and damp housing have been shown to contribute to illness. Children living in damp houses are likely to have higher rates of respiratory illness, symptoms of infection and stress (Marsh et al 1999). These will be exacerbated by overcrowding. The high accident rates to children in social class V are associated with high-density housing where there is a lack of play space and opportunities for parental supervision. Psychological and practical difficulties accompany living in high-rise flats and isolated housing estates, which may adversely affect the health of women at home or older people.

Employment and health

Work is important to consider as a social determinant of health:

There has been considerable interest in how the psychosocial environment of work can affect health (Marmot et al 2006). Most research has identified high demands and low control over work decisions as contributing to job stress and cardiovascular risk. These factors together with the amount of social support people get at work have been confirmed in workplace studies in many developed countries (see Chapter 14 for further discussion). There is also a considerable body of evidence, mostly gathered in the 1980s, that unemployment can damage health (McLean et al 2005). It is however uncertain whether unemployment itself can lead to a deterioration in health or whether it is the poverty associated with unemployment which contributes to the poor health of the unemployed.

It seems that unemployment has a profound effect on mental health, damaging a person’s self-esteem and social structure. Part of its effect on health must also arise from the material disadvantage of living on a low income and social isolation (McLean et al 2005).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

BOX 2.1

BOX 2.1

BOX 2.2

BOX 2.2 BOX 2.3

BOX 2.3 BOX 2.4

BOX 2.4 BOX 2.5

BOX 2.5