drug use, alcoholism, or malnutrition. Other risk factors include penetrating head trauma, otorrhea, rhinorrhea, or neurosurgical procedures. Also, living in close quarters such as college dormitories or military barracks can enhance the spread of meningitis; and travel to endemic areas such as sub-Saharan Africa is also a risk factor for meningitis.3

TABLE 29-1 COMMON CAUSATIVE ORGANISMS OF BACTERIAL MENINGITIS IN ADULTSa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

meningitis in children and adults. These bacteria attach to mucous epithelium by secreting a substance known as immunoglobin A (IgA) protease and then enter the bloodstream. In the blood, bacteria are inactivated by complement-mediated bactericidal activity and phagocytosis by neutrophils. However, protection from these mechanisms is afforded by a capsular polysaccharide coating. Bacteria that are able to survive in the circulation enter the CSF through the choroid plexus of the lateral ventricles and other areas of the altered blood-brain barrier. The CSF is an area of impaired host defense because of a lack of sufficient numbers of complement components and immunoglobulins for the opsonization (the rendering of bacteria and other cells subject to phagocytosis) of bacteria.9

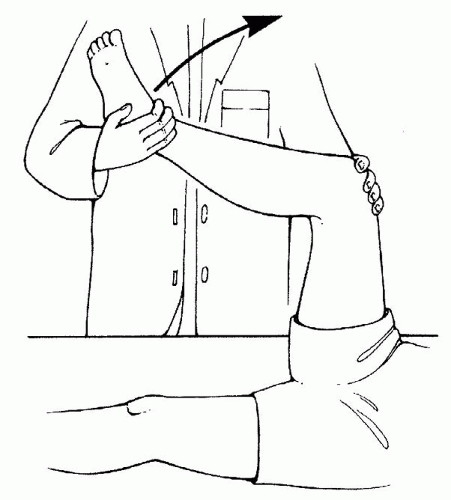

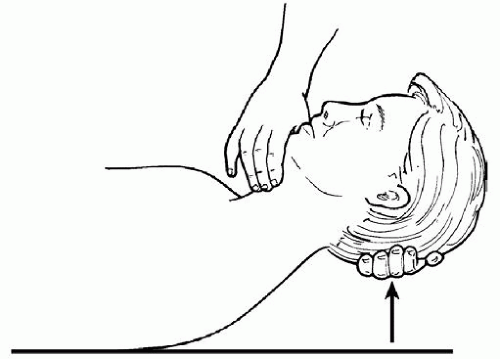

of the meninges and spinal roots. The spasms are a protective mechanism to deter painful flexion. Brudzinski’s sign is positive when passive flexion of the neck and head to the chest causes spontaneous involuntary flexion of both the hips and knees (Fig. 29-2).11 This reflex is caused by irritating exudate around the roots in the lumbar region.

Increased opening pressure on LP

Polymorphonuclear leukocytic pleocytosis

Decreased glucose concentration

Increased protein concentration

Glucose ratio less than 40 mg/dL

White blood cell (WBC) count of CSF usually more than 100 cells/mm33 and often more than 1,000 cells/mm33

Protein count higher than 45 mg/dL (most often 100 to 500 mg/dL)

TABLE 29-2 COMPARISON OF THE CLASSIC CEREBROSPINAL FLUID (CSF) FINDINGS IN ACUTE BACTERIAL MENINGITIS AND ACUTE ASEPTIC (VIRAL) MENINGITIS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

administered intravenously every 6 hours for the first 4 days of therapy.9, 19, 20 However, studies have shown that dexamethasone significantly decreases the efficacy of vancomycin penetrates into the CNS and achieves therapeutic concentrations, this is especially important in highly resistant S. pneumoniae.19 Concurrent use of a histamine-2 receptor antagonist or a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) is recommended to prevent gastrointestinal (GI) hemorrhage. Prophylactic use of anticonvulsant therapy is recommended by some to prevent seizures because about 40% of patients will have a seizure. Other physicians choose to begin phenytoin or levetiracetam (Keppra) only if the patient has had a seizure.

TABLE 29-3 EMPIRIC ANTIMICROBIAL THERAPY FOR BACTERIAL MENINGITIS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 29-4 RECOMMENDED ANTIMICROBIAL THERAPIES BY ORGANISM FOR BACTERIAL MENINGITIS IN ADULTS | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree