CHAPTER 16 Infection prevention and control

An overview of the problems with and management of health care associated infection and infectious diseases

The latest HCAI prevalence surveys in adult patients were conducted in 2006 in acute hospitals across England, Wales, Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland (Smyth et al 2008) and in 2005–2006 in both acute and non-acute hospitals in Scotland (Reilly et al 2008). The results estimate the prevalence of HCAI to be between 7.3 and 9.5%, which means that at any one time approximately one in eight patients could have an HCAI. Infections associated with invasive procedures and the use of medical devices such as intravascular devices and urinary catheters account for a high proportion of HCAI. Prevalence and incidence results in the UK also reiterate the fact that common microorganisms like those that have already been mentioned continue to cause problems.

It had been thought that up to one third of all HCAIs would be preventable by better application of proven methods of prevention (Haley et al 1985, Harbarth et al 2003). However, more recently it has been claimed that certain HCAIs, in particular central venous catheter-related bloodstream infections, could potentially be eliminated (Pronovost et al 2006). The nurse has a crucial role in achieving this, as described in this chapter.

Infection prevention and control measures aim to reduce the burden of HCAI and other infectious or communicable diseases, on individuals, health care organisations, and within the National Health Service as a whole. The Health Protection Agency, Health Protection Scotland and Departments of Health in all UK countries coordinate many activities, such as national surveillance and control programmes, in order to highlight and act upon the actual burden in specific settings (see Useful websites, p. 515). Nurses are well placed to contribute to the prevention, control and management of infection within health care settings and beyond. Indeed, nurses occupy a wide diversity of roles, including those concerned with public health, providing ever-increasing opportunities to influence the health protection and patient safety agendas.

For further information about the national burden of HCAI and spread of other infectious diseases, see the recent national prevalence surveys (Reilly et al 2008, Smyth et al 2008), National Audit Office reports (2000, 2004, 2009), the Care Quality Commission’s work, the UK Health Department websites, the Health Protection Agency and Health Protection Scotland websites (see Useful websites, p. 516).

How infection spreads

Microbiology

Bacteria

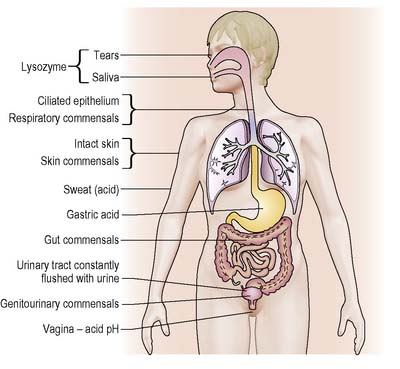

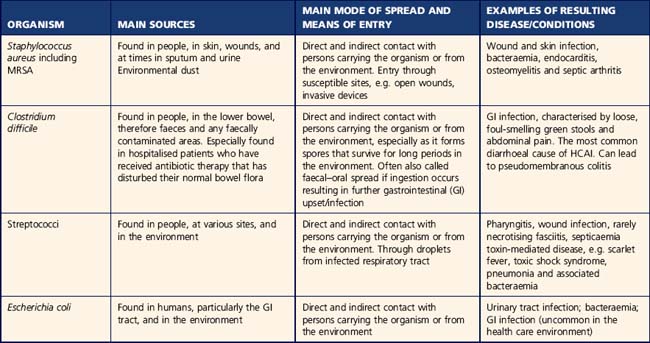

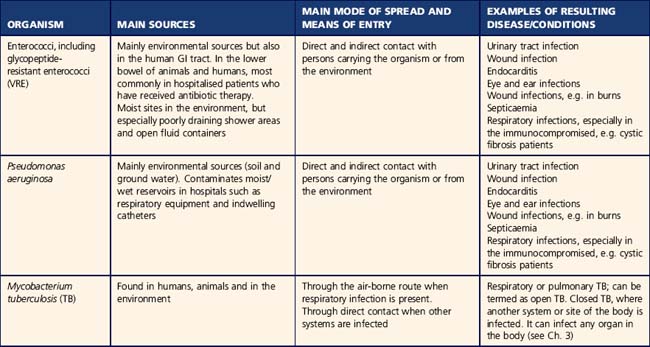

Bacteria, including variations of the microscopic beings such as mycoplasmas, rickettsiae and chlamydiae, are small microorganisms of simple primitive form. Bacteria are commonly found living within the human body and in the environment, for example in soil and water. Those species of bacteria capable of causing disease in humans are known as ‘pathogens’. Some are more ‘pathogenic’ than others. Most are acquired though contact with other people or the environment (i.e. ‘exogenous’ sources). Table 16.1 gives some examples of pathogenic bacteria commonly encountered while providing health care. Bacteria that constitute the normal commensal flora within the body are not normally pathogenic (Table 16.2). However, in certain situations, such as when these bacteria gain access to a different anatomical location within the body, they can cause disease. This is known as ‘endogenous’ infection. It is not always clear when infections are exogenous or endogenous.

Table 16.2 Normal commensal microorganisms

| Site | Organism |

|---|---|

| Skin | Staphylococcus epidermidis |

| Diphtheroids | |

| Corynebacterium sp. | |

| Mouth and throat | Staphylococci |

| Streptococci | |

| Anaerobes | |

| Neisseria sp. | |

| Nose | Staphylococci |

| Diphtheroids | |

| Gut | Escherichia coli |

| Klebsiella sp. | |

| Proteus sp. | |

| Streptococcus faecalis | |

| Clostridium perfringens | |

| Yeasts (Candida) | |

| Kidneys and bladder | Normally sterile |

| Vagina | Lactobacilli |

| Streptococci | |

| Staphylococci | |

| Anaerobes |

Routes of transmission

The infection prevention team

The role of the infection prevention team (IPT) has been defined and includes the utilisation of the risk management approach (see p. 505), provision of relevant specialist advice, ensuring appropriate measures and action plans are in place and supporting sustained improvement through a change of culture throughout their health care organisation. The team has clear accountability for reporting infection prevention and control progress and issues through relevant management structures, such as clinical governance and patient safety committees and, at times, directly to chief executives. The infection prevention doctor (IPD) and infection prevention nurse (IPN) have clear responsibilities within the health care organisation. More recently, leadership and management roles, including the Nurse Consultant, Director of Infection Prevention and Control (in England and Wales) and Infection Control Manager (in Scotland) have added to the structure.

Many settings also have infection prevention link personnel to enhance the effectiveness of the work of the team. The link person in a ward, department or community team receives additional education to improve the communication between infection prevention and control teams and the clinical setting and may assist with clinical audit and awareness of clinical staff in relation to Standard Precautions (see p. 507).

The nurse’s role in infection prevention

Nurses in the UK have a duty of care as stated in the Health and Safety at Work Act (1974) to prevent, control and manage infection. Nurses, as the largest staff group in health care, have a responsibility to deliver care based on the best available evidence or best practice (Nursing and Midwifery Council [NMC] 2008). This includes preventing the spread of infection, ensuring they do not put themselves and others at unnecessary risk from infection. In England and Wales, The Health and Social Care Act (DH 2008, p. 2) requires health care professionals to ‘demonstrate good infection control and hygiene practice’.

The health of nurses while at work is also important. Nurses should:

Diagnostic sampling

The collection of specimens for microbiological examination is an important element of a nurse’s role. It enables identification of microorganisms to aid diagnosis and ensure appropriate treatment. In the case of bacterial infection, accurate diagnosis enables the use of narrow-spectrum rather than broad-spectrum antimicrobial agents, which optimises treatment and reduces problems associated with antimicrobial use. A sample may also be taken for screening purposes, e.g. to exclude previous known infections or as part of contact tracing. The UK countries currently have a range of policies on screening for antimicrobial-resistant organisms and, in particular, MRSA (see Useful websites p. 516).

Epidemiology

The risk management approach

The risk to health from infection is one of many risks to be managed in health care settings. The risk management approach to HCAI was developed during the 1970s as part of the growing health and safety agenda around the developed world. The World Health Organization (WHO 2008) definitions provide a basis for the risk management approach in relation to infection prevention and control:

Hazards and risks from microorganisms are present in our environment at all times. Once they are identified, appropriate control measures and action plans must be adopted to ensure that the greatest time and resource is spent in the areas with the greatest risks of infection. For example, the approach to the management of MRSA within the health care environment varies according to the risk to patients. In the hospital environment and, in particular, wards and units where patients are deemed to be at high risk of infection with MRSA, such as intensive care units and orthopaedic surgical wards, a more stringent approach to screening, decolonisation treatment and the isolation of patients colonised or infected with MRSA may be taken, as compared with community settings such as care homes and the patient’s own home (Box 16.1). As hazards and risks may change over time, up-to-date guidance on infection prevention and control measures is required for the health and safety of patients and staff.

Box 16.1 Reflection

Mr Brown’s journey

The results from Mr Brown’s MRSA screen and foot ulcer yielded MRSA.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree