Chapter 30 Infection due to Penicillium marneffei

Introduction

Penicillium marneffei infection is one of the most common opportunistic infections in persons with advanced human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection in Southeast Asia, northeastern India, southern China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. In northern Thailand. It is one of the four most common opportunistic infections, which include tuberculosis, cryptococcal infection, and Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia [1]. Cases have also been reported in HIV-infected patients from the USA, Europe, Japan, and Australia following visits to the endemic area [2]. Diagnosis depends on familiarity with the clinical syndrome and a high index of suspicion. This can be problematic when the patient presents for medical care outside the endemic area. As in other systemic fungal infections, confirmation of the diagnosis requires demonstration of the fungus in the infected organ and culturing the organism from clinical specimens. The response to antifungal treatment is good if the treatment is started early. After the initial treatment, the patients need prolonged suppressive therapy to prevent relapse at least until their immune system is sufficiently restored by antiretroviral therapy.

Epidemiology

Penicillium marneffei was first isolated from a bamboo rat in Vietnam in 1956 [2]. It is the only known Penicillium species that exhibits temperature-dependent dimorphic growth. At temperatures below 37°C, the fungus grows as mycelia with the formation of septate hyphae, bearing conidiophores and conidia typical of the genus Penicillium. At 37°C on artificial medium or in human tissue, the fungus grows in a yeast-like form with the formation of fission arthroconidium cells. The fission yeast cells represent the parasitic form of P. marneffei. This form is seen in the intracellular infection of the macrophages as well as extracellularly.

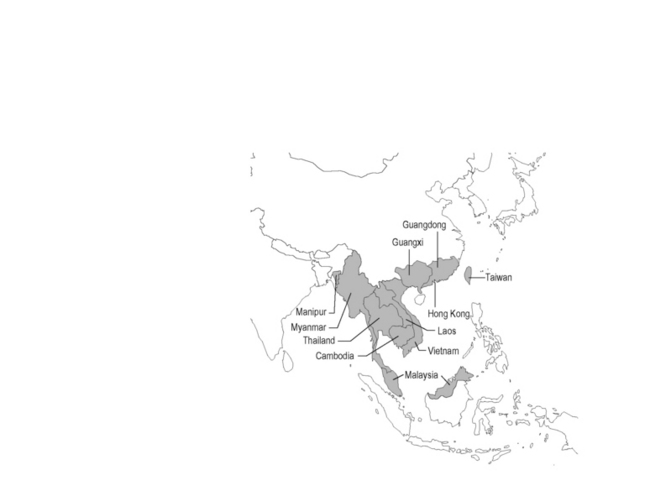

The first naturally infected case was reported in 1973 in an American missionary with Hodgkin’s disease who had been living in Southeast Asia. Between 1973 and 1988 less than 40 cases of P. marneffei infection had been reported in the literature [3]. The rarity of P. marneffei infection changed when the global HIV/AIDS epidemic arrived in Southeast Asia. The first case of P. marneffei infection in an HIV-infected native of Southeast Asia was reported in 1989 from Bangkok. The number of cases has markedly increased since then. At one tertiary hospital in Chiang Mai, northern Thailand, a total of 1,592 patients with P. marneffei infection were seen between January 1991 and December 2000; almost all of these patients were also infected with HIV. Patients would typically be in the late stage of HIV disease with CD4 count <100 cells/mm3. Common manifestations were fever, anemia, weight loss, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, and skin lesions. Cases had been reported in 21 children with perinatally acquired HIV infection from the same hospital. The clinical manifestations in these children were similar to those in adults [4]. There is extensive seasonal variation in the incidence of P. marneffei infection, with increased number of cases in the rainy season [5]. Between 1991 and 2003, more than 6,000 cases of P. marneffei infection in HIV-infected patients were reported to the Thai Ministry of Public Health (MOPH). However, between 2006 and 2010, when the Thai MOPH free access to antiretroviral program was fully implemented, the average number of cases reported to the MOPH fell to 148 cases per year. As the HIV/AIDS epidemic spread in the region, the incidence of P. marneffei infection has also increased in other countries, including Vietnam [6], India [7, 8], China [9, 10], Hong Kong [11], and Taiwan [12]. Figure 30.1 shows the endemic area of this fungal pathogen.

Natural History and Pathogenesis

Many important features of the natural history and pathogenesis of P. marneffei infection remain unknown. Human and bamboo rats are the only known animal hosts. The fungus can infect four species of bamboo rats: namely, Rhyzomys sinensis, R. pruinosus, R. sumatraensis, and the reddish-brown subspecies of Cannomys badius [13]. These infected animals showed no signs of illness. The geographic ranges of these bamboo rats (Cannomys spp. and Rhizomys spp.) broadly follow the distribution of human cases of P. marneffei infection: namely, Southeast Asia, northeastern India, and southern China [14]. This suggests that bamboo rats may be an obligate stage in the life cycle of the fungus. However, an attempt to epidemiologically link bamboo rats and human infection was not successful. Chariyalertsak and colleagues compared 80 patients with AIDS who had P. marneffei infection with 160 AIDS patients who did not have P. marneffei infection, in a case–control study [15]. The main risk factor found was a recent history of occupational or other exposures to soil, especially during the rainy season. Both cases and controls were often familiar with and had seen bamboo rats; 31.3% of cases and 28.1% of controls had eaten bamboo rats but this difference was not statistically significant. Reported cases of P. marneffei in HIV-infected infants also suggest that human and bamboo rat infection are not connected [4]. Bamboo rats live in the wild and have limited or no contact with these infants. In another study from Chiang Mai, it was found that disseminated P. marneffei infections have been markedly seasonal, with a doubling of cases during the rainy season [5]. This suggested that there might be an expansion of the environmental reservoir with favorable conditions for growth during these rainy seasons and that both humans and bamboo rats are infected with P. marneffei from this common reservoir. A recent genotypic study of P. marneffei isolated from humans and bamboo rats in China also supports the existence of a common reservoir [16]. However, attempts in culturing the fungus from environmental sources, for example, soil samples, air samples (using high-volume air samplers), domestic animals, and vegetation including bamboo, have been unsuccessful [17, 18].

The mode of transmission of P. marneffei to humans is not known. Analogous to other endemic fungal pathogens, such as Coccidioides immitis and Histoplasma capsulatum, it is likely that P. marneffei conidia are inhaled from an environmental reservoir. Also by analogy to histoplasmosis, it is likely that subclinical infections with P. marneffei may occur commonly in persons living in endemic areas who are exposed to the fungus in nature. The existence of subclinical infection in humans is supported by a case report from Australia of an HIV-infected patient who had a latent period of more than a decade between exposure in an endemic area and the subsequent onset of clinical infection in Australia [19]. However, in many other instances, the clinical appearance of disseminated infection occurred within a few weeks of exposure to the organism. The seasonal variation of cases with disseminated P. marneffei infection, as well as cases of P. marneffei in HIV-infected infants reported from northern Thailand [4], also suggest that progress from infection to clinical dissemination is usually brisk. There is no evidence of person-to-person spread.

Clinical Features

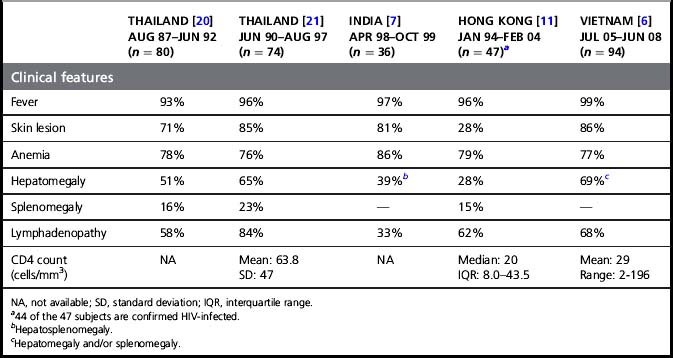

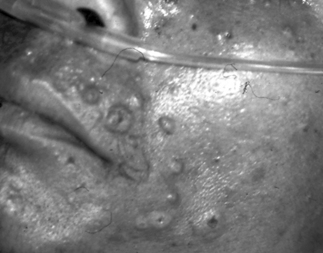

Penicillium marneffei infection occurs late in the course of HIV infection. The Thai MOPH as well as the health authority of Hong Kong have included P. marneffei infection as one of the AIDS-defining illnesses in those countries [11, 20]. The CD4 count at the time of the diagnosis of P. marneffei infection is usually <100 cells/mm3. Cases were reported in which P. marneffei infection occurred with other late HIV-related infections, such as cryptococcal meningitis, Pneumocystic jiroveci pneumonia, cerebral toxoplasmosis, tuberculosis or Salmonella bacteremia. Table 30.1 shows the more common clinical presentations of HIV-infected patients with P. marneffei infection from case series from Thailand [20, 21], India [7], Hong Kong [11], and Vietnam [6]. Patients commonly present with symptoms and signs of infection of the reticuloendothelial system. These include fever, generalized lymphadenopathy, hepatomegaly, and splenomegaly. Clinical manifestations associated with late HIV infection such as anorexia, asthenia, anemia, diarrhea, weight loss, and cachexia are also seen in the majority of the patients. Other presentations, such as skin lesions, mucosal lesions, and bone and joint infection [22], are secondary to dissemination of the fungus via the bloodstream. Skin lesions are seen in more than 70% of the patients in most case series and, when present, are the best clues to the diagnosis (see Fig. 30.2). They are usually found as papules on the face, chest, and extremities. The center of the papule subsequently becomes necrotic, giving the appearance of an umbilicated papule (also called papulonecrotic skin lesion or molluscum-contagiosum-like skin lesion). Biochemical and hematologic laboratory values are non-specific and may include elevation of liver enzymes and bilirubin, anemia, and leukocytosis or leukopenia. In patients with symptoms and signs of the respiratory system, the chest radiograph may show diffuse reticular infiltration, diffuse or localized alveolar infiltrates, or pleural effusion [23].

Table 30.1 Clinical features of HIV-infected patients with Penicillium marneffei infection from 5 case series

Figure 30.2 Skin lesions of HIV-positive patient with P. marneffei infection.

Some of the papules had central umbilication resembling lesions of molluscum contagiosum.

Reprinted from the Lancet. From Supparatpinyo K, Khamwan C, Baosoung V, et al. Disseminated Penicillium marneffei infection in southeast Asia. Lancet 1994; 344:110–113. Copyright Elsevier 1994.

As the HIV epidemic spread and more patients were seen, other less common clinical presentations of P. marneffei infection in HIV-infected patients were encountered. Cases with chest radiographs showing lung mass or single or multiple cavitary lesions have been reported [24, 25]. Bone infections have been reported in the ribs, long bones, flat bone of the skull, mandible, lumbar vertebrae, scapula, and small bones of the fingers. Arthritis involving both large peripheral joints and small joints of the fingers has been seen [22]. Ukarapol and colleagues reported three children who presented with fever, mesenteric lymphadenitis, and abdominal pain. Two of the patients had had unnecessary abdominal operations for the diagnosis of peritonitis and acute appendicitis, respectively. All three cases had positive blood and bone marrow cultures for P. marneffei [26]. Kantipong and colleagues reported six patients who presented with fever, hepatomegaly, and markedly elevated serum alkaline phosphatase levels. Penicillium marneffei was demonstrated in the liver and cultured from the blood [27]. Mucosal lesions in the oral cavity, oropharynx, hypopharynx, stomach, colon, and genitalia have been reported [20, 28–30]. Penicillium marneffei could be demonstrated in or cultured from these lesions. Twenty-one patients from Vietnam whose cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) culture grew P. marneffei have been reported. They presented with fever and symptoms of altered mentation including confusion, agitation, or drowsiness. Symptoms of increased intracranial pressure and signs of meningeal inflammation were uncommon. CSF pleocytosis was seen in only one-third of the cases. A total of 71% of the cases had elevated CSF protein and 24% had a CSF glucose/serum glucose ratio <0.5. The disease course was rapidly progressive with a high mortality rate [31].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree