System development

From birth to age 1 year, remarkable changes occur in the infant’s neurologic, cardiovascular, respiratory, and immune systems.

Neurologic system

The central nervous system (CNS) is the fastest growing system during the infancy stage, as brain cells continue to develop in both size and number. The effects of a poor environment, including nutritional deprivation, can’t be reversed when experienced during this early stage.

Hold your head up!

Myelinization refers to the development of a myelin sheath around nerve fibers. Myelin enables quick, efficient transmission of nerve impulses. Myelinization of the neurons occurs in a cephalocaudal (head-to-toe) direction, although it takes up to 2 years for the entire process to be completed. An infant progresses from being unable to hold up his head to being able to hold himself in an upright position, sit, and keep his head erect.

Extreme CNS makeover

As myelinization reaches the extremities, the infant can put weight on his legs and use them to stand up. As the brain and CNS develop, more sophisticated cognitive and behavioral skills follow.

Converge, stare, and search

Vision development is also tremendous. At birth, the newborn prefers facial features, but by 8 weeks, the baby is alert to moving objects and is attracted to bright colors and lighted objects, such as toys with flashing lights and an otoscope light. Convergence and following with the eyes are jerky and inexact. By ages 4 to 6 months, the baby has bifocal vision and can stare and search. By age 1 year, distance vision and depth perception have markedly improved.

Cardiovascular and respiratory systems

The cardiovascular and respiratory systems undergo dramatic changes at birth. Because of placental oxygenation, the fetus shunts a majority of blood away from the lungs while in utero.

Cardiopulmonary drama

At birth, a cascade of physiologic changes occur, and deoxygenated blood begins to circulate to the lungs, where it receives oxygen and is then pumped out to the rest of the body through the left ventricle of the heart. Within moments, the cardiovascular and respiratory systems are functioning at essentially the same way as those of an adult.

Immune system

The immune system develops over the first year of life. The neonate depends on maternal antibodies received in utero or via breast milk for immunologic protection. By ages 6 to 8 weeks, an antigen-antibody response is maturing and can be triggered, for example, by immunizations, and by age 9 months, the infant is developing his own immunity.

Physical development

The physical growth and development that take place during infancy are astounding. Although patterns of growth and development will occur in a predictable order, it’s important to remember that the rate at which they occur may vary among children of the same age. Also remember that the most reliable way to interpret growth measurements is to follow their trend over time using growth charts. Pediatric growth charts have been used in the United States since 1977. Growth charts consist of a series of percentile curves that depict the distribution of selected body measurements in infants and children. Many infants have their length, weight, and head circumferences measured and plotted on standardized growth charts. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that nurses and other pediatric health care providers use the World Health Organization’s (WHO) growth standards to monitor growth for infants and children ages 0 to 2 years in the United States and use the CDC growth charts for children age 2 years and older in the United States.

Height, weight, and head circumference

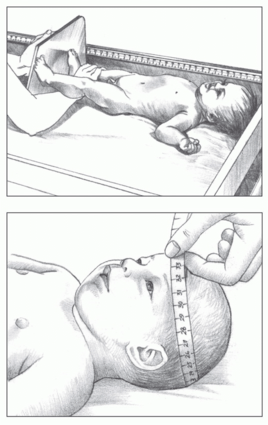

Intrauterine growth is assessed by measuring height, weight, and head circumference. These parameters are also the basis of growth evaluation for the rest of the infant and toddler period.

Height

Until the child is age 24 months, height, or length, is measured in the supine position, from the top of the head to the bottom of the heel. When measuring the infant, it’s important to keep his body as straight as possible to achieve an accurate measurement. An infant’s length is best measured using a stadiometer.

Trunk first, legs to follow

At the end of the first year, the infant’s birth length has increased by 50%, with growth of approximately 1” (2.5 cm) per month for the first 6 months, followed by about ½” (1.3 cm) per month for the second 6 months. Most of this growth occurs in the trunk rather than in the legs.

Weight

Weight ideally is measured on an infant scale with a bucket-type area in which the infant can lie down or sit. Weight is the primary indicator of nutritional status; changes in weight can also be used to assess hydration status. The average infant will double his birth weight by age 5 months, and triple it by age 1 year.

Head circumference

Head circumference, or occipital frontal circumference, is measured by placing a measuring tape around the largest diameter of

the head, from the frontal bone of the forehead to the occipital prominence at the back of the head.

Don’t get a big head

A head circumference that’s smaller, or lags behind the height and weight of an infant, may indicate inadequate brain growth. A head circumference that increases rapidly may indicate an increase in ventricular fluid and intracranial pressure (hydrocephalus). (See

Measuring height and head circumference.)

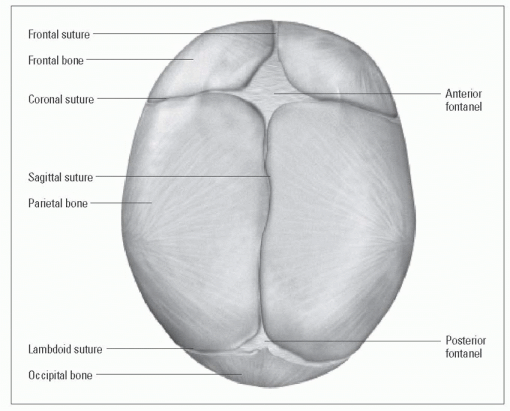

Fontanel changes

The anterior fontanel is formed at the intersection of the sagittal, frontal, and coronal suture lines. The averazge size of the anterior fontanel is 2 cm by 2 cm at birth. It remains open for up to 18 months and gradually closes as the head grows.

The posterior fontanel is formed at the intersection of the sagittal and lambdoid suture lines. The average size of the posterior fontanel is 1 cm by 1 cm at birth. It’s usually closed by age 2 months.

Palpation and pulsation

In infancy, the fontanels are assessed by palpation. The fontanel should feel soft and flat. You may be able to see pulsations at the anterior fontanel; this is a normal finding. A bulging or tense fontanel may indicate increased intracranial pressure. A sunken fontanel indicates dehydration. The nurse may auscultate the fontanel to assess for bruits.

Teeth

Most neonates don’t have teeth. Occasionally, a “natal tooth” will be present at birth and should be evaluated by a pediatric dentist because they may become loose and pose a risk of aspiration. Neonatal teeth are teeth that erupt within the first 28 days of life.

A little drool, a big eruption

The average age at first tooth eruption is 8 months. Most infants start drooling and mouthing hard objects months beforehand.

Gross motor development

Gross motor skills refer to the child’s development of skills that require the use of large muscle groups. (See

Developmental milestones.) They include:

posture

head control

sitting

creeping/crawling

standing

walking.

The infant will attain gross motor control in a cephalocaudal manner, progressing from the head to the toes. He can lift the head, then sit, stand, and, eventually, walk.

Fine motor development

Fine motor skills refer to the infant’s ability to use his hands and fingers to grasp an object. As the infant grows, he begins to refine his fine motor skills to grab small objects and feed himself.

Normal infant reflexes

Much of a neonate’s behavior is controlled by reflexes. At ages 4 to 8 weeks old, many of these reflexes reach their peak—especially the sucking reflex, which affords nutrition (and, therefore, survival) and psychological pleasure.

At age 3 months, the most primitive reflexes begin to disappear, except for the protective and postural reflexes (blink, parachute, cough, swallow, and gag), which remain for life. (See

Infant reflexes.)

Psychological development

Psychological development involves language development and socialization as well as play and cognitive development.

Language development and socialization

Language development and socialization begin as soon as the neonate is born. Initially, the neonate communicates primarily through crying and socializes through some of the reflexive behaviors such as the grasp reflex. However, he’ll make tremendous strides in these areas during his first year of life.

Cry me a river

The infant cries to express needs. During the first 3 months, crying usually signals a physiologic need such as hunger. As the

infant grows, he may cry for attention, from fear, or from frustration during the trials of mastering new skills. Parents usually become adept at translating their child’s cry.

Infants who cry frequently and are difficult to console may be at increased risk for abuse. To help parents prepare for and effectively deal with crying infants, the pediatric nurse should:

reinforce that there are times when infants cry for no reason at all

assess how parents cope with fussy periods and offer support as needed

teach parents comforting techniques, such as holding, swaddling, and massaging.

Smile and say “eh”

An infant’s vocalization develops from cries. By age 2 months, the infant can produce single-vowel sounds, such as “ah” and “eh,” and he begins to develop a social smile. The social smile is the infant’s first social response; it initiates social relationships, signals the beginning of thought processes, and further strengthens the bond between parent and child. By ages 3 to 4 months, the infant can coo and gurgle and laugh in response to his environment.

Stranger danger

By age 6 months, the infant begins to experiment with sounds and attempts to imitate others. He can discern one face from another and exhibits stranger anxiety—he’s wary of strangers and clings to or clutches his parents. Separation anxiety may also develop at this period and peaks around 9 months.

I’d like to buy a vowel

By ages 7 to 9 months, the infant can verbalize all vowels and most consonants but speaks no intelligible words. He’ll focus intently on the mouth of someone speaking to him. He can also understand simple commands such as the word “no.” He may imitate the expressions of others and may be able to play pat-a-cake. He can recognize and respond to his own name.

Just the facts

Just the facts Growing pains

Growing pains Growing pains

Growing pains