Chapter 7. Induced or accelerated labour

Introduction

A large proportion of women experience induction of labour. More than 20% of women in England underwent this procedure during 2005–6 (The Information Centre 2007). Usually invasive, and often resulting in additional discomfort, this intervention must be managed with care and sensitivity. Student midwives need to develop an understanding of the indications for induction and acceleration of labour, the underlying principles and potential consequences. This chapter aims to address some of the most salient issues, with particular emphasis on providing woman-focused care.

Induction of labour

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), in its clinical guideline (NICE 2008:xii), defined induction of labour as ‘the artificial initiation of labour’. The rates of induction and augmentation of labour have significant geographical variation (Williams et al 1998). Also, despite the publication of NICE guidance (NICE 2001, 2008) with the aim of supporting evidence-based care, a wide variation in current practice continues.

Investigation in this area of obstetric practice is complex because of the many variables that can potentially combine. Not only are there many ways in which induction of labour can be attempted – for example, with prostaglandin preparations – but there is also a range of doses and routes of administration. The rationale for induction of labour, gestation of the pregnancy and favourability of the cervix are additional considerations that need to be taken into account when examining the literature.

Reasons for inducing labour

Post-maturity

The risk of stillbirth and neonatal mortality increases with post-maturity. In a large retrospective analysis of birth outcomes and subsequent survival to 1 year (Hilder et al 1998), it was found that the risk of stillbirth increases six times from 0.35 per 1000 total births at 37 weeks’ gestation to 2.12 per 1000 at 43 weeks’ gestation. Following a systematic review of the evidence (Gülmezoglu et al 2006) it was concluded that routine induction of labour after 41 weeks’ gestation improves perinatal mortality compared to waiting for spontaneous labour. Induction of labour is therefore recommended between 41 and 42 weeks’ gestation (NICE 2008).

Not all women wish to accept intervention, and would rather wait and see what happens. Heimstad et al (2007) conducted a randomized controlled trial to determine the outcome of expectant management with serial fetal surveillance(every third day) versus induction of labour at 41 weeks’ gestation. There were no significant differences between the two groups with regard to mode of birth or neonatal morbidity. Women in the induction group were more likely to have a precipitate birth and a shorter second stage of labour.

However, a study designed to determine the cost-effectiveness of induction of labour versus serial monitoring while awaiting spontaneous labour reported an increase in caesarean section in the expectant group (Goeree et al 1995). There were no differences in perinatal mortality, but the cost of expectant management was greater because of the increased rate of caesarean. NICE guidance (2008) recommends that serial monitoring should be initiated at 42 weeks, for women who decline induction of labour, and should include twice-weekly cardiotocography and ultrasound estimation of the single deepest pool of liquor.

Pathology

The benefits of induction of labour must be carefully weighed against the potential hazards. Where maternal or fetal pathology exists or is suspected, the outcome may benifit if the pregnancy were brought to a swift conclusion.

Ruptured membranes

NICE guidance (2007) recommends that woman who have pre-labour ruptured membranes should be offered induction of labour approximately 24 hours after the membranes had ruptured. The guidelines go on to state that if a woman chooses to await events for more than 24 hours she should record her temperature every 4 hours whilst awake and report any change in the colour of her vaginal loss. In a rare survey of women’s views about induction, Hodnett et al (1997) compared women’s preferences for induction of labour or expectant management in women with pre-labour rupture of membranes at term. Women in the induction group were less likely to report additional worry, or that there was nothing they liked about the treatment, than women in the expectant group.

Mental health

In rare circumstances, a woman may be so fearful about going into labour that induction provides a welcome alternative to escalating anxiety and distress. Such intervention enables the labour to progress in a more controlled pattern, and care to be provided by a known midwife. The woman’s care should also be planned in liaison with the mental health team so that a psychiatric assessment can be undertaken. Women who are anxious antenatally require careful monitoring and support in the postnatal period as they are more likely to go on to suffer from postnatal depression (Areskog et al 1984).

Social

Occasionally, it becomes necessary to expedite birth due to extenuating social circumstances. Examples of such situations include: partners of servicemen who are only allowed fixed leave from duty; single women who have limited support from family or friends and for whom the birth can be arranged to fit in with special arrangements; and the terminal illness of a close friend or relative. Each case must be judged on its own merits, and the woman must be carefully informed about the associated risks. NICE (2008) recommend that induction for maternal request is audited.

Contraindications to induction of labour

Induction of labour should not be attempted where there is placenta praevia, transverse or oblique lie and/or suspected cephalopelvic disproportion. Induction should not be considered if there is evidence of severe fetal growth restriction with confirmed fetal compromise (NICE 2008).

A woman who has had a previous caesarean section has a scar on her uterus; extreme caution is therefore essential when induction of labour is being considered. An American study (Sims et al 2001) was conducted to determine the safety and success of trial of labour in women who were induced compared with those who had a spontaneous labour. It found that women whose labour was induced were less likely to achieve a vaginal delivery (58% compared with 77% in the spontaneous labour group), and that 7% had separation of the uterine scar. They concluded that induction of labour in women aiming for vaginal birth after caesarean section is associated with a significant risk of serious maternal morbidity.

Impact of induction of labour

Induction of labour has been shown to impact on the subsequent mode of birth. In a retrospective cohort study of 14409 women, induction of labour increased the risk of caesarean section for both primiparous and multiparous women, independent of other risk factors such as maternal and gestational age (Heffner et al 2003). Having made the decision that delivery is the best course of action, failing to induce labour may also result in emergency caesarean section.

With this adverse consequence in mind, it is important that the most effective means of inducing labour are employed. Current practice involves activities to prime or ripen the cervix prior to instigating further interventions. The use of some of the methods and preparations available will now be described.

Methods of induction

Cervical priming

In the last weeks of pregnancy the cervix begins to soften and efface (ripen). This process is enhanced if the presenting part of the fetus and forewaters are well applied to the cervix as this pressure will increase the release of local prostaglandins. Cervical priming is an intervention with the aim of stimulating uterine activity and speeding up the ripening process.

The ripeness of the cervix is assessed during vaginal examination. One way of describing the consistency of the cervix that is sometimes used to help students is to compare the consistency of your nose (firm) with that of your lips (soft). Bishop (1964) developed a score to make this assessment more objective, a summary of which is given in Table 7.1. Each aspect of the assessment is given a score, and the total of all five aspects is the ‘Bishop’s score’. An unfavourable cervix (for induction of labour) has a Bishop’s score of four or less, whereas women whose cervices have a score of eight or more have the same chance of vaginal delivery as someone who went into spontaneous labour (Chamberlain & Zander 1999).

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position of cervix | Posterior | mid-position | anterior | – |

| Consistency of cervix | Firm | Medium | Soft | – |

| Cervical length or effacement | 3cm not effaced | 2cm partially effaced | 1cm almost effaced | 0cm fully effaced |

| Station of presenting part (cm above ischial spines) | 3cm above | 2cm above | 0–1cm above | Below ischial spines |

| Dilation of the cervix | 0cm | 1–2cm | 3–4cm | 5–6cm |

Interventions for cervical priming and induction of labour

Membrane sweep

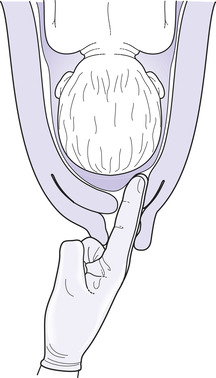

This technique is employed with the intention of hastening the onset of regular uterine contractions. It is performed during vaginal examination and involves insertion of a finger through the cervical os and, in a circular movement, separating the amnion from the lower uterine segment. This procedure is sometimes accompanied by an additional stretching of the uterine os by the examiner’s fingers and is then termed ‘stretch and sweep’ (Fig. 7.1).

|

| Fig. 7.1 Sweeping the membranes. (From Johnson & Taylor 2006, with permission.) |

Implementation of this procedure has been somewhat ad hoc, with some practitioners offering it to all women who return to the antenatal clinic after their expected date of birth. Others have taken the view that it is an uncomfortable procedure that may lead to bleeding, pre-labour rupture of membranes and irregular contractions. A systematic review of membrane sweeping for induction of labour concluded that, although the procedure did reduce the need for induction of labour by drugs, this advantage should be carefully weighed against potential for discomfort and unpleasant side-effects (Boulvain et al 2004). However, the NICE (2008) guidance advocates that this procedure should be offered to nulliparous women when reviewed after 40 weeks’ gestation and all women at 41 weeks’ gestation. It is therefore essential that women are informed of the potential side-effects as well as the advantages to enable them to make a decision that is right for them.

Mechanical methods

The first methods for inducing labour were mechanical and although not currently in widespread use their effectiveness has been explored in a systematic review (Boulvain et al 2001). The methods reviewed included catheters inflated in the cervical canal and laminaria tents. The review concluded that there is insufficient evidence to recommend their use although compared with the use of oxytocin in women whose cervix was not favourable, mechanical methods were associated with a lower casearean section rate.

Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2)

PGE2 is an effective agent for ripening the cervix (D’Aniello et al 2003). It is available in either tablet, gel or pessary form, all of which, according to a systematic review (Kelly et al 2003), appear to be as efficacious as each other. The authors also concluded that lower dose regimens (total dose of less than or equal to 3mg) appear as efficacious as higher dose regimens (total dose of more than 3mg).

NICE guidance (2008) recommends that either PGE2 vaginal tablets, gel or slow release pessary should be used as the method of preference. Doses of PGE2 tablets or gel can be repeated every 6 hours (maximum two doses) whereas only one dose of slow release PGE2 should be given in 24 hours. Intravenous, extra-amniotic, intracervical or oral PGE2 is not recommended for induction of labour (NICE 2008).

Care: First impressions

Historically, women have sometimes been admitted to an antenatal/postnatal ward in the evening for vaginal PGE2 with the aim of having artificial rupture of membranes and successful induction of labour the following day. However, NICE guidelines recommend that induction should commence in the morning as this is associated with enhanced client satisfaction (NICE 2008). When a woman is admitted to the maternity unit for induction of labour, it is particularly important that she feels treated as an individual. To be greeted in a way that acknowledges that her arrival was expected is an important first step. Showing her to her bed bay with her name already displayed can help convey this. Her hospital notes should already be on the ward. Some women will go into spontaneous labour before they reach the antenatal ward; for this reason, some units do not make preparations for their arrival so as not to ‘waste time’. However, to be expected and to have this demonstrated in whatever small level of preparedness can build the woman’s confidence in the system.

Some maternity units have a specially allocated induction suite. This can help women to be cared for in an environment where care is focused on particular needs rather than shared between women who are ill or who have already had their babies.

One issue that is often difficult to manage is if the woman’s partner has to leave shortly after the prostaglandin has been administered. This is a time when the woman may feel vulnerable and alone, not sure when to ask for attention or what the long night might hold. Some induction facilities enable partners to stay overnight using a put-up bed, thus providing a family-focused approach to care.

If your unit has a policy that enables women to return home after administration of PGE2 she should be asked to contact the midwife if she does not have any contractions after 6 hours or when contractions begin (NICE 2008).

Admission procedure

The documentary side of this process will have common elements to any admission to the ward. However, the woman need not be aware that you have undertaken the same process three times already that day. She needs to feel that you are focused on her and that you are making efforts to get to know her and her unique circumstances.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree